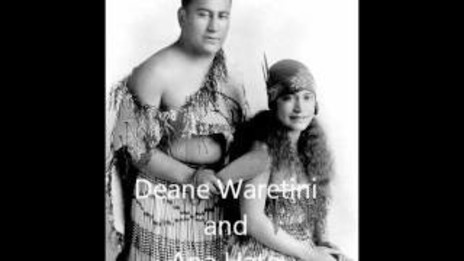

As Hato’s cousin, the great baritone Deane Waretini, reminisced in the liner notes of The Great Songs of Ana Hato and Deane Waretini (Parlophone, 1963), “we, as children, were quick to appreciate the monetary advantages of the tourist trade, diving for pennies … thrown by the tourists … [and performing] impromptu entertainments”. As a child, Ana Hato learnt waiata early on, and was also immersed in Te Reo, Tikanga Māori, and Māori folklore.

While the young Ana was gaining recognition for her vocal abilities, her talents also leant towards the athletic. She was a sports enthusiast: a strong swimmer, rugby, and basketball player, and she also represented Rotorua at Hockey – in 1925 her team won the Auckland Provincial tournament.

Singing in Te Reo to tribal audiences and tourists gave her confidence and developed her sophisticated style.

However, music was where her path lay, and Hato sang continually for family, for tourists, and often for money. A soprano whose exceptional singing voice came from her mother’s Te Rangi family, singing in Te Reo to tribal audiences and tourists gave her confidence and developed her sophisticated style.

Hato and Waretini were taught music by the Whakarewarewa School headmaster’s wife, Mrs Banks, whose influence on their singing was long lasting. The pair sang at home, at community gatherings, and in the church choir, their harmonies and vocal interchange drawing on the music they grew up with. Hato’s pitch was precise, and though she could play the ukulele, she did not read music – Waretini calling her “outstanding … she remained so for the rest of her life.”

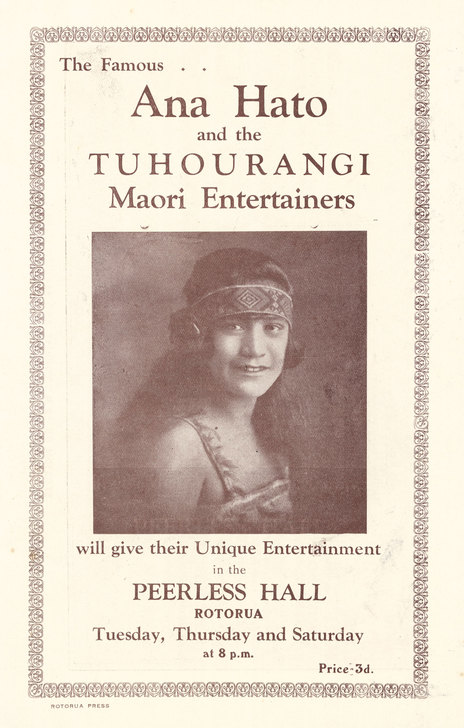

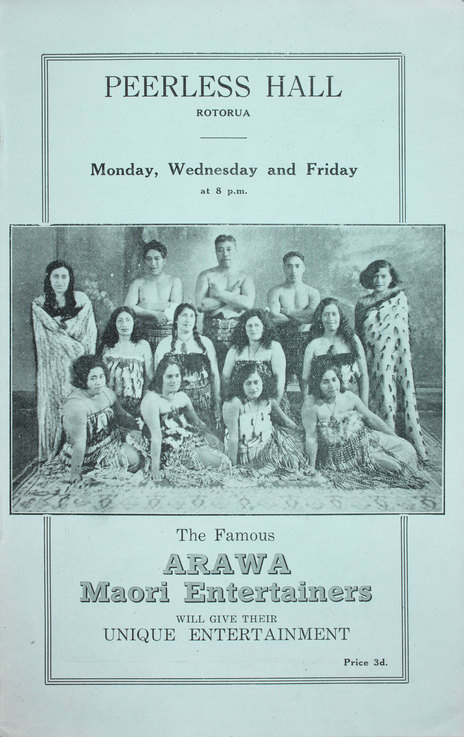

After watching her parents and sisters perform in concert parties, at age 16, she was invited to join Guide Rangi’s (Rangitīaria Dennan) Concert Party. Her reputation grew, and she was in great demand as a soloist, touring in the early 1920s with Maggie Papakura’s Concert Party.

By 1925 she was soloist in a small concert party led by Guide Eileen that went to Australia. Naturally, Hato was the star performer, and she travelled extensively throughout her life with concert parties. By 1926, Waretini considered Hato the best soprano in New Zealand, and she was thought to be a leading prima donna.

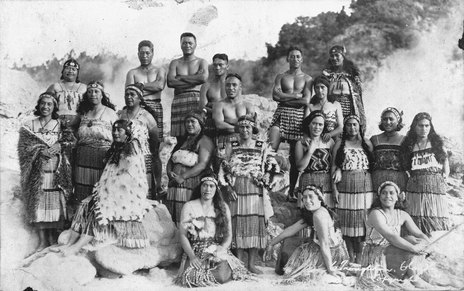

Hato led her own concert party in 1933, which included Guides Bella and Eileen, and members of the Tūhourangi iwi, and organised concerts for Māori serving in World War II. In 1941, she sang for the opening of the 1ZB building in Auckland, and the opening of 1YZ radio station in Rotorua. According to the Rotorua Daily Post, Hato taught Gracie Fields to sing ‘Now Is The Hour’ when the singer visited New Zealand in 1946.

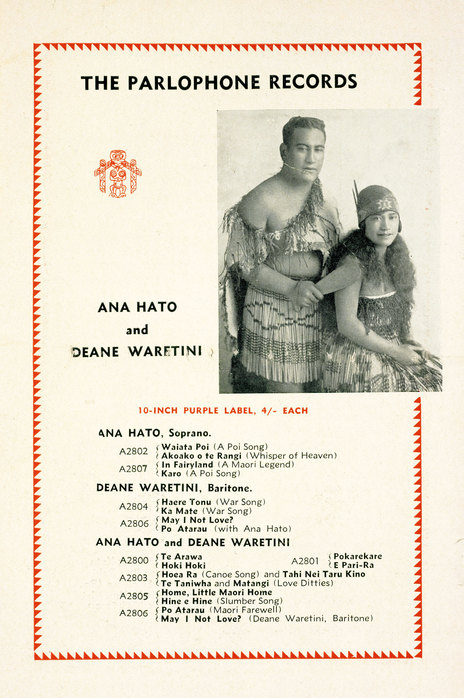

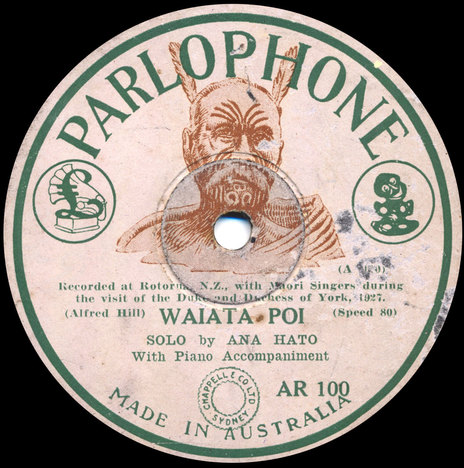

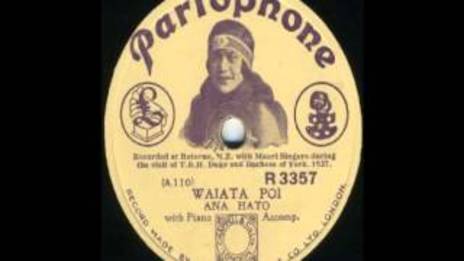

In 1927, at age 20, Ana Hato and Deane Waretini entered the local history books when their performance for the Duke and Duchess of York (later King George VI and Queen consort) in Rotorua was recorded on small portable acoustic equipment by technicians from Parlophone Records’ Australian branch. This was the first locally recorded commercial music to be released on shellac 78rpm disc. According to music historian Chris Bourke, Parlophone wanted to record vocalists in all countries, though their interest lay in in what was popular, not what was purely an authentic cultural experience.

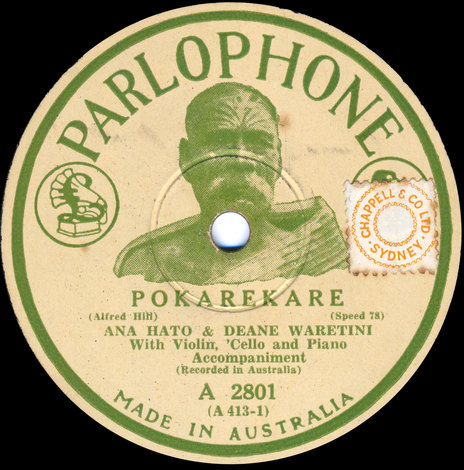

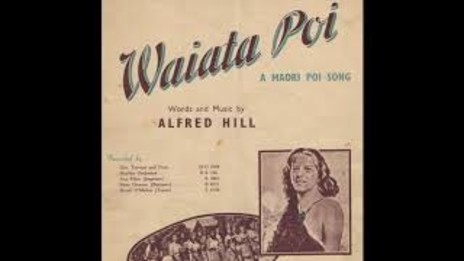

Hato sang 16 songs at the Tūnohopū meeting house in Ōhinemutu, Rotorua that day in February 1927, some with Waretini, others with soloist Te Mauri Meihana, and some with the nascent Rotorua Māori Choir. The titles they sang were favourites for Māori and Pākehā, and included ‘Te Arawa’, ‘Hine e Hine’, ‘E Pari Rā’, and ‘Waiata Poi’. These recordings were very successful, becoming popular locally, and Chris Bourke suggests Hato’s version of ‘Pōkarekare’ accelerated the popularity of the song around New Zealand.

In 1929, the pair travelled to Sydney (staying in Bondi), where, backed by violin, cello, and piano, they electronically recorded material (nine discs worth) for Parlophone, including re-recording some of their 1927 session. These recordings were again very successful in Australasia, and were in the label’s catalogue for the next 20 years. However, according to Hato’s niece Bubbles Mihinui, it was unlikely they got paid, stating “probably the only time they received any money was when they … maybe got 5s a night for performing.”

Hato did not record again until the 1950s, when she and Waretini recorded songs by E.H. R. Cross – ‘Give me Your Love’ and ‘One More Day Tomorrow’. These recordings remained unreleased in the vaults for nearly 50 years before being preserved by the Alexander Turnbull Library, and released in 1996 on Ana Hato – raua ko Deane Waretini, Legendary Recordings 1927-1949 on the Kiwi label.

Staunchly Catholic, Hato was generous with her talents and time, giving concerts to raise funds for the Catholic Church. In 1929 she was crowned Queen during the Catholic Queen Carnival in Rotorua, later treating the audience to a rendition of ‘E Pari Rā’. Her involvement with the Catholic Church also led to her contribution to the restoration of Saint Michael’s Catholic Church.

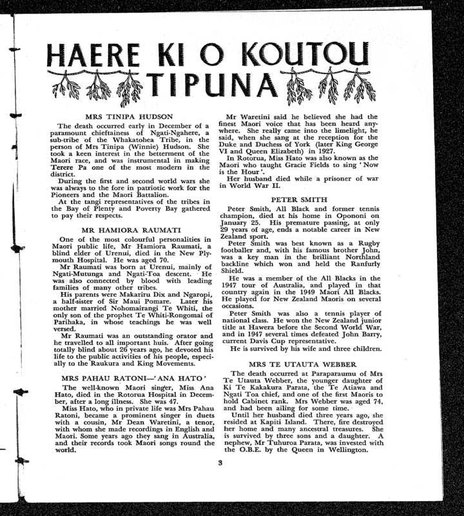

Hato married twice – first to one of her Pākehā friend Arthur Black (the marriage ended within a few months), and then in 1931 to labourer and Tūhourangi kinsman Pāhau Rāponi. Her second marriage, according to Mihinui, was happy, and Rāponi was supportive of Hato. The marriage ended in 1942 with Rāponi’s death in a prisoner of war camp in Germany, after being wounded in the battle of Crete. Ana Hato had no children of her own, but adopted the daughter of her niece, naming the baby Te Rangimaria or Ria for short.

While famous for her musical talents, Ana Hato did not become wealthy from her music, and made her living as a housemaid at the Waiwera, Princes Gate, and Geyser Hotels, a cook in a hospital kitchen, and a laundry worker. Drawing on her background with tourists, she worked as a guide for European visitors when needed. Hato continued to sing, and one story goes that when Ngāti Porou vocalist Tuini Ngāwai visited her in Whakarewarewa, the pair sang until dawn, and the neighbours never closed their doors or windows.

In the later years of her life, Hato suffered from breast cancer (she had the first symptoms while playing football in 1945), and was often hospitalised in the years before her death. After cancer forced her to give up the singing she loved around 1950, the illness took over and she died on December 8, 1953, aged 46. She was buried at Whakarewarewa among her Tūhourangi people.

Ana Hato’s voice had a singular quality to it, something that Bubbles Mihinui labeled, “hotu … it’s like a catch, a sob … it’s crying, but without tears.” Pianist Hamuera Mitchell (also of Ngāti Whakaue) concurred, saying Hato had a “voice of calibre, trueness in purity and register … unique”, and described her vocal work as “in the Māori way”, with an emotive, sobbing quality. Hato could hold a note for a long time with no hint of vibrato, and her pure voice had an extensive range.

Hato and Waretini’s recordings found a new audience in the digital era when they were reissued on CD in 1996, though the original, fragile, 78rpm discs are still prized by collectors and music historians. If there is one line to sum up Ana Hato’s extraordinary contribution to New Zealand music, it would be taken from her memorial notices: “The melody is ended, but the memory lingers on …”