In the mid-1980s, the mainstream New Zealand music industry was in crisis, mostly caused by a lack of support for local music from radio stations – including RNZ’s commercial wing – which made the major record companies reluctant to sign more than a few local acts. It would be the early 2000s – and a decade’s work from the music section of NZ On Air – before the relationship became more mutually supportive.

A two-day convention was held in Wellington in April 1987 to discuss the issues. At times, the exhaustive debate became heated. The convention was attended by 250 interested parties: musicians, promoters, record companies and radio stations. This article first appeared in Rip It Up, in May 1987, headlined ‘The Vinyl Solution: Songs of Innocence and Experience’.

--

The success stories were easy to spot at the first Kiwi Music Convention held in Wellington on April 7-8, 1987. They were pinned up behind the panelists, like icons to emulate: posters of Kiri Te Kanawa, Dave Dobbyn, Herbs, and Crowded House. The latter group – whose ‘Don’t Dream It's Over’ was that week climbing the US charts – became a symbol over the two days, of everything that was wrong, and right, with the New Zealand music industry. (During the convention, the single would reach No.3 in the New Zealand charts, after reluctant early airplay from local stations.)

Looking at the posters were 250 people, from Southland solo performers to Auckland multi-national managing directors, gathered to discuss the ills of the industry. Before you had even walked in the door of the hotel it was obvious that one issue was going to dominate the convention. Outside was a small picket line, with Andrew Fagan resplendent in psychedelics and Skank Attack playing on the pavement, calling for a radio quota.

The quota lobby were dubious about the convention, with some justification: it had been organised by the 18-month old New Zealand Music Promotion Committee, which had no policy on the quota issue, in deference to the differing views of its members. With the quota issue currently being considered by the cabinet, did the radio and record company people dominating the committee want to present a united front to the government – “Everything’s hunky dory, thanks, we don’t need a quota”?

But the strong turnout from such a diverse array of people involved in music, all of whom have strong opinions on the subject, meant the event was more than the “painting over the cracks” that some people had feared.

Phil Warren, reading Rip It Up at the Kiwi Music Convention, 1987. - Jocelyn Carlin

Opening the convention, Record Industry Association president Tim Murdoch said the New Zealand music industry was coming of age; when a similar conference had been mooted seven years ago, only one person showed any interest out of the hundreds canvassed: Phil Warren. Promoter Ian Magan made the first reference to Crowded House, then at No.5 with a bullet on the US charts. New Zealand music, he said, needs to aim for success in the international marketplace for its survival and growth. The ironies of the Crowded House achievement were to provide plenty of ammunition in the discussions which followed.

“Creativity isn’t just stifled in New Zealand, it’s stuffed”

Creativity is the topic of the first seminar, but composer Dave Fraser stresses the importance of having a professional approach to making a living from music: “Form a limited company, register for GST ... talent alone will not get you to the top, the business part is crucial.” Dave McArtney discusses the lonely profession of songwriting, “but the hardest thing to take is going into the studio with young bands, knowing their music is never going to be played.” The battle lines are drawn.

Composer/conductor William Southgate deplores the lack of government assistance to New Zealand music. “We don’t understand the cultural importance of music, we don’t put a value on it. Finland spends $45 a head on the arts, does [our government] spend five dollars? No country faces our spiritual dearth. The Arts Council lacks funding – which has to come from the Government as well as industry.”

Battle proper commences with some heartfelt, hard-hitting words from longtime quota campaigner Ray Columbus. Twenty-five years after the NZBC had said “do cover versions, don’t try and write your own songs” and ‘She’s A Mod’ was ignored here until it was successful overseas, Columbus says “Nothing has changed. Crowded House suffer from the same disease. New Zealand doesn’t need sanctimonious patronising garbage after the fact from radio. Chris Dickson and KZ7 got support before their success. New Zealand music is just as good as our sport.

“Creativity isn’t just stifled in New Zealand, it’s stuffed. Without radio and major record company support, the dollars will continue to flow into Australia. [Minister of Broadcasting] Jonathan Hunt, we’re waiting for the quota. Apparently caucus is not pro-quotas – in an election year! I can’t believe it! Unless there’s an escalating quota from this Labour Government, I suggest you migrate to Australia. If you prosper there, you’ll be popular in New Zealand.”

“The sheep in this country are supposed to be in the paddocks,” concludes Columbus.

Murray Cammick, at the Kiwi Music Convention, 1987. - Jocelyn Carlin

The convention is now fired up after his outburst. But first Minister of Overseas Trade Mike Moore has to give a belated opening address. It’s a standard marketing pitch: “Government has a vested interest; New Zealand is a partner in your success ... New Zealand music lives – it lives in Australia. As Minister of Trade, I’m keen to stop that export... Rice and Webber are worth more than the Dairy Board, Abba were bigger than Volvo ...” The quota lobby are disheartened by his aside “Whatever happened to that petition?” Snatching the opportunity, John MacRae of Wellington quickly gives Moore, the master of self-promotion, a copy of his latest single.

“Musicians seem more interested in their sunglasses”

It’s generally agreed at the management panel that there’s a shortage of managers about. “It’s a frustrating job,” says Herbs’ manager Hugh Lynn, “you handle your artists’ lives, and their wives and children.” It’s also a job with no set rules, says promoter Brian Sweeney. “You’re dealing with hotel managers, DJs, hire companies, people with power, people who want power.” Wages, music, doortakes, venues, all come under the manager’s brief. It’s an important role, to instill objectives in the group, to know where they’re going, when to quit and when to go for the big break.”

Professionalism among musicians is lacking, says Sweeney. “Actors and dancers are proud of their craft and look after themselves; musicians seem more interested in knowing where their sunglasses are.”

Mike Corless of New Music Management laments the demise of the pub circuit, listing a dozen familiar band names from the early 80s, all hard workers who put out records, and all lost money and broke up. Now, a Hello Sailor costs $120,000 to mount. “Without sponsorship, it’s impossible,” he says. The two areas not giving enough support? Record companies – and radio.

Hugh Lynn, at the Kiwi Music Convention, 1987. - Jocelyn Carlin

Phil Warren, who has been in the business since Johnny Devlin trod the boards, says times have changed – the money men took over in the mid 70s. “Taking a punt is now a rare thing, it’s all percentages against costs, and guarantees. Money men are in it for a return on their investment.”

“It’s about commercial exploitation”

Next up come the money men: financiers and support services. Noel Agnew, musician and lawyer, cautions: “The most important contract you will sign is a publishing contract. Get your act together at the outset – get professional advice before signing any contract. Be organised before the big tax bill or bogus T-shirts turn up, so the artist gets not just a chunk, but a slice of the action.”

Chris Bourn outlines TVNZ’s inability to do more for music – 40 percent of the entertainment budget has been cut – while Ashley Heenan discusses the role of APRA and the Composers Foundation. “Every time music is played [on record or live] a royalty is collected ... You must be a member of the performers’ right organisation to get support. It costs nothing to join APRA.”

From Fay, Richwhite comes merchant banker John Paine. “The business we’re in is raising money for investors; they’re in it for a return, not sponsorship.” Opportunities exist for cooperation between record companies and financiers, he says, but the tax write-off/special partnership situation has changed since the “witch-hunt” of the IRD into the film industry. “Partnerships are now limited to 25 people ... it’s not hard to get $50,000 from associates or friends ... work through an accountant or lawyer, do your homework, and remember: it’s about commercial exploitation.”

The Arts Council position is outlined by Brendan Smyth, music advisory officer. He refers to the recommendations of a music seminar held in the early 80s in Hamilton: reduce the (then) 40 percent sales tax, establish a recording commission along the lines of the Film Commission, and impose a local content quota on radio. “New Zealand is too small to sustain an industry by itself. The future lies in marketing our music internationally.”

“It’s not a hand-out business ...”

“Multinationals are not necessarily a dirty word,” says Michael Glading of CBS, at the recording and publishing panel. “What Men at Work achieved brought benefits to Australia.” However the multinational publishing companies could be more active here, he says. “Publishing companies give artists their first break – that’s sadly lacking here.” Gilbert Egdell, CBS A&R person, stressed the importance of trust in a good relationship between artist and record company.

“Hold on to your publishing, it’s the most valuable and negotiable agreement you’ll sign,” says Tim Murdoch of WEA, who maintain a publishing company for local artists. “I say to bands, form your own company, and hence we’ve got Maui, Warrior and Hit Singles. It’s in the interests of the New Zealand artist to have larger control of their own destiny.” The multi-nationals, says Murdoch, “have a moral obligation to look after local industries.” But he sees an inconsistency between multinationals being criticised for operating here, while local companies receive praise for their marketing initiatives overseas. (Surely market dominance comes into it too, however.)

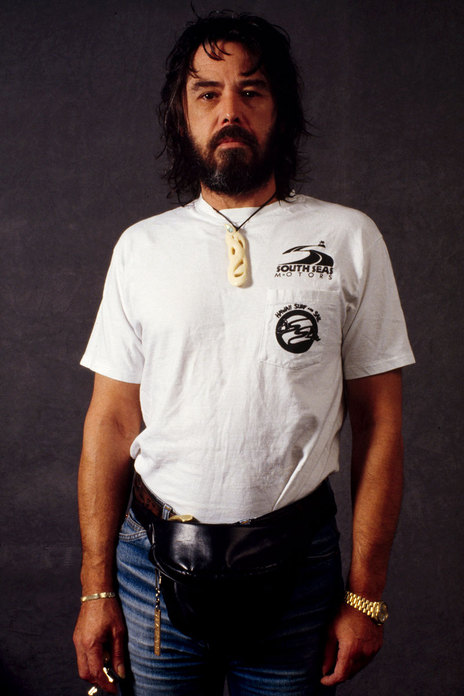

Tim Murdoch, photographed in 1986 by Jocelyn Carlin

“People choose to be musicians,” says Murdoch. “There are a lot of starving musicians worldwide. What keeps them going is the big payoff. Despite the support services available, it’s not a hand-out business.”

Murdoch is not a supporter of quotas. “Make no mistake – quotas are censorship. If we have pride in our music, radio will have pride.”

Animosity towards the big record companies emerges at question time. The managing directors are understandably cagey when they’re asked how much money they put into local music last year. “Over $100,000” says Glading. “Fifty percent of our profits,” says Murdoch.

Ray Columbus asks what happened to the deal the record companies allegedly made with the Arts Council at the time of the sales tax argument. In return for the Arts Council’s support for the removal of sales tax, says Columbus, the record companies agreed to support the Council on a local music quota. John McCready, ex-CBS, now of Radio Hauraki and a critic of quotas, throws in a red herring: “Private radio pays $1.5 million in royalties to publishers. How much of it goes back into New Zealand music?” Sure, if multinational record companies are expected to contribute locally, so too should publishers. But those royalties are for the overseas music that radio plays – Ashley Heenan pointed out that APRA returns more money to New Zealand music by way of the Composers’ Foundation than New Zealand music earns in royalties.

“Profiteering is the main criteria ...”

Temperatures have suitably risen for the showdown of the convention: the radio session. “We have here a distinguished panel of parasites,” says Chris Muirhead of Radio Windy. Karyn Hay is sitting as far away from her fellow panellists as she can without falling off the rostrum. “The music and radio industries are not the same thing,” says Muirhead. “Radio programmes are there to make money – not as promotions for a record.”

What follows is radio speak. Hauraki’s Ross Goodwin talks of “market segmentation and music formatting,” pleasing “the radio user who creates the demand – Mr and Mrs Mt Albert.” Peter Fryer talks of the “methodology of research” and RNZ’s contribution to recording local bands live – Street Talk, Hello Sailor, Th’ Dudes, 10 years ago now – and broadcasting to the mass, not special-interest sub-groups, which goes against Goodwin’s argument that the more stations there are, the narrower their audiences will become.

Charles Mabbett, representing the student radio stations, gives an alternative viewpoint. “All six student stations are different, but are united in an undying, fanatical love of New Zealand music.” He outlined how the student stations support local music: cheaper ad rates, spontaneous interviews, compilation LPs, three or four local songs an hour. But, he acknowledged, some local music doesn’t fit their format: “We wouldn’t play Crowded House, for example,” he said wryly. “Also, lots of people don’t like us. But if playing New Zealand music is radical ... that’s not a very good situation.”

Karyn Hay, at the Kiwi Music Convention, 1987. - Jocelyn Carlin

Karyn Hay, whose involvement in the quota petition last year was undoubtedly a catalyst for the convention’s existence, didn’t use understatement in her condemnation of the radio industry. She was aghast at what she’d heard from the commercial radio spokesmen. “So profiteering is the main criteria, not contribution to New Zealand culture ... I’m ashamed to be in their company. They seem to be bereft of any cultural obligation.

“The radio quota is the single most important issue facing the New Zealand music industry,” she says, deftly turning around the claim that quotas were censorship: “It’s censorship to deny the New Zealand public the right to hear its indigineous music.”

How, she asks, can radio stations ignore the requirement in their warrants [or, in RNZ’s case, in their legislative charter] to reflect and make a contribution to New Zealand culture? There is no response from the radio representatives.

It’s been an exhausting day, hearing issues that have been thrashed out many times before amongst individuals finally thrashed out by the factions of the industry. With all the negative talk, things aren’t looking good, and Auckland musician Ivan Zagni sums up the mood by saying from the floor, “This industry is stuffed. There is no communication. We’ve got one day to solve it.”

Fane Flaws, at the Kiwi Music Convention, 1987. - Jocelyn Carlin

Thankfully, after the bloodletting first day, the convention has a constructive mood on the second. On the film and video panel Fane Flaws outlines the differences between making videos in Australia and here, where video makers are often expected to work for nothing: “Don’t do it.”

Radio With Pictures has taken a budget cut every year, says Peter Blake of TVNZ, so they’re not making local videos anymore – instead they’ll be concentrating on live specials and magazine reports. “Hopefully not making clips is a positive step,” he says – TVNZ clips not being able to compete with overseas clips in quality. That puts the onus on the record company to make the clips. An export video show of New Zealand music is mooted, and Arthur Baysting urges: “Target people, write to politicians about the quota, do it yourself, now.”

(How about writing quick letters to the Ministers of Arts, Broadcasting, Internal and Maori Affairs, plus the Prime Minister, telling them how much – in this election year – New Zealand music needs a radio quota ... no stamps required!)

“Why are the discos packed?”

“If you can’t cut it live, don’t bother,” says industry all-rounder Graeme Nesbitt, who opens the performance panel. “It’s all very well wanting video clips and vinyl, but you’ve got to get an audience, and you’ve got to get them to pay.” That means cut down those guest lists, too: “Grocers don’t give goods to their friends, why should musicians?” Dave Fearon, manager of Peking Man, discussed the improvements that could be made in pubs to encourage audiences, and asked, “Why are the discos packed? It’s all very well playing what you want to play, but the public are paying to see what they want to hear.” He stressed the value of hard work: “Young bands expect it on a plate: record contract and airplay. They’re not prepared to put in the work for four years.”

Dalvanius, at the Kiwi Music Convention, 1987. - Jocelyn Carlin

The promotion panel seemed stacked with radio people, but proved one of the most immediately constructive sessions. Radio’s not the only tool for promotion, and Jayrem’s Jim Moss and Rip It Up’s Murray Cammick gave advice on how retailers and the press can contribute. But when it comes to using the media, the master is Dalvanius, and – as always – he stole the show: “The media is there to be manipulated. I can fart and get it on the front page ... flog it to the ears that don’t get flogged.”

The chairmen of the panels went away to formulate some recommendations that reflected the attitudes of the convention. Would the New Zealand Music Promotion Committee come back in favour of quotas? The convention was stunned when they did; the radio people had “offered an olive branch” and said they could live with a quota – as long as the record companies provided the material.

The five recommendations (see below) meant that those who attended the first Kiwi Music Convention came away feeling positive about the future for New Zealand music.

The Recommendations of the First Kiwi Music Convention (abridged) were:

1. A compulsory 10 percent music quota on all New Zealand radio stations, with re-evaluation by the committee for subsequent increases

2. New Zealand record companies should help radio stations meet that quota by moving immediately to record a wide variety of music

3. That the recent heavy cuts to TVNZ’s light-entertainment budget be deplored

4. That the absence of international music publishers in New Zealand, and consequent lack of support for developing musicians, be regretted

5. An endorsement of the Arts Council’s recommendations for the establishment of a recording commission

--

Transcriptions of the presentations at the 1987 Kiwi Music Convention were edited by Arthur Baysting and published in a book, Getting Started in the Music Business: a Survival Manual for NZ Musicians (Ode Records, 1989).

A very weary Ian Magan, after moderating two days of contentious panels at the 1987 Kiwi Music Convention in Wellington. Magan’s role was a very big task, said Tony Chance of RIANZ in the closing moments. “To come up here and front to everyone, to control the situation and a forum that we thought could have got out of hand, and just get it going and get positive results out of it. I can’t think of anyone else in the country that could have done it.” Magan replied, “Thank you very much. It's over.” Photograph taken by Jocelyn Carlin at the convention, 1987.