For over thirty-eight years, from 1975 onwards, Jim Moss and Jayrem Records have been releasing New Zealand music domestically and overseas, and distributing hard to find international records inside New Zealand.

Jim Moss’s Jayrem Label reflects New Zealand’s Diverse music communities in the 1980s

Everything from rap, punk, hard rock and heavy metal to indigenous reggae in Te Reo, poetry, women’s music, 1960s reissues and electronic sounds. Jayrem has a catalogue, which includes over 200 albums and 1,200 copyrights. Based in Wellington then Masterton, Moss’s style is low key but never unproductive.

If you want to find a record label which reflects the diversity of New Zealand’s music communities and the music they made in the 1980s, you need look no further than Jim Moss’s busy, open minded Wellington indie imprint Jayrem Records. Therein lies evidence of the capital city’s vibrant and diverse 1980s indie music culture and New Zealand’s response to the fresh surge of heavy metal and hard rock, politicized indigenous reggae, punk rock and rap. Women’s music is also strongly represented, as are poetry and musical forebears who could still muster the passion and the songs. The Legenz imprint was added in the 1990s for New Zealand 1960s pop and rock compilations.

Moss’s inclusive taste stretched to distributing smaller Wellington-based indies such as (late era) Ripper, Braille, Eelman and Skank Records, who were pushing free jazz, post-punk, young horn driven R&B and soul onto the New Zealand record buying public.

Record and Cassette Distribution becomes Jayrem

Established in 1975 in Wellington as Record and Cassette Distribution, Jayrem Records hit its stride in 1981 after Moss resigned as EMI marketing manager. Being the owner of the Chelsea Records chain with shops throughout the North Island helped as did Moss’s ear for overseas music with a local fan base, including reggae, which he compiled.

At heart Jayrem Records was a Wellington label whose roster reflected rising cultural groups in the city and wider community. The Māori renaissance was in evidence in the assertion of te reo on releases by Māori artists and groups. Women musicians were heavily represented, including Fran Walsh, future film director Christine Jeffs, the ever productive Charlotte Yates and Jan Hellriegel, who presaged the influx of women into popular music in the 1990s and beyond. Punk releases spoke of that community’s ongoing issues with politics and police.

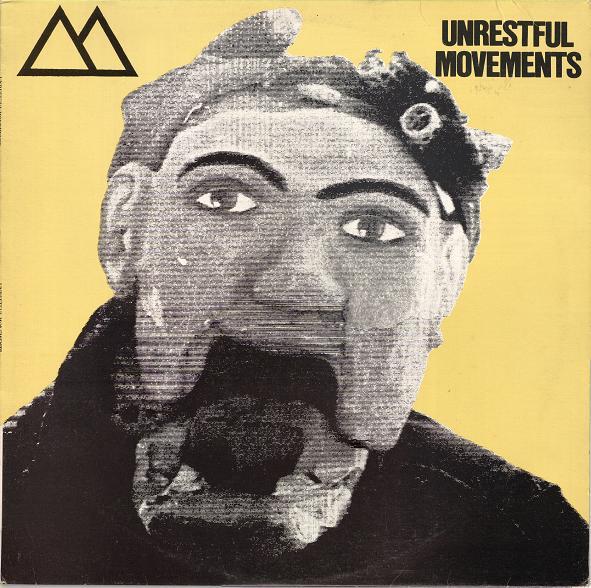

The 1982 Unrestful Movements EP was a strong seller for Jayrem

Yet for all the politics it fostered Jayrem’s was a quiet radicalism. Groups were on Jayrem. They were not Jayrem groups. The label had little more profile than it needed. A comparative anonymity was reflected in the plain imprint logo and bland colours of its generic Jayrem label. Unlike most New Zealand indies it had no manifesto, preached no cultural mantras, had no house style (or non-style) and it never trumpeted or tried to mediate involvement. It let the music do the talking, allowing, people come to it in their own time and way.

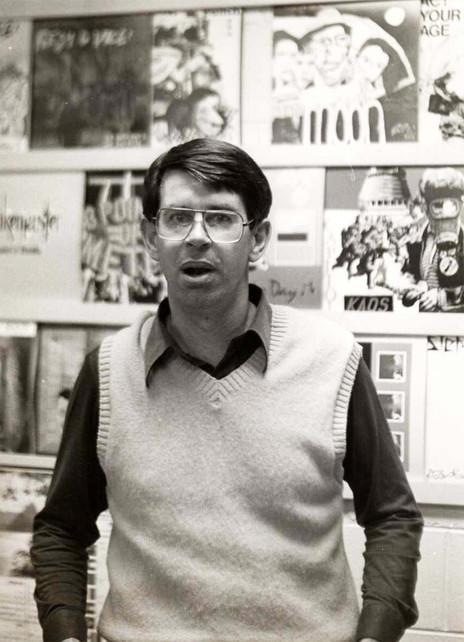

Jim Moss, in Chelsea Records, 1980s. - Jim Moss collection

Diversity and open mindedness were Jayrem’s strengths although in the 1980s they were looked upon as weakness. Diversity meant diffusion of focus. Dilution. When John Dix dismisses Jayrem Records in Stranded In Paradise for being broad-based like a record company, it’s no compliment. The tenor of the time was for indies to be tightly defined and clannish – nationalistic and mono-cultural, as opposed to multi-cultural. In marked contrast Jayrem evidenced indie music in New Zealand as a broad church.

Artistic and commercial successes

Being worthy didn’t mean the music wasn’t compelling. There were chart successes in te reo by influential Māori band Aotearoa and a monster electronic pop hit with The Body Electric’s ‘Pulsing’ in 1983, which sold over 5,000 copies. A follow-up single and album were also hits and there were plenty of creative triumphs in the large body of work the label released.

IQU's 'Witchcraft', a 12-inch single that featured Ryan Monga from Ardijah, was a substantial club and underground hit, charting in 1984

All these musical forms had a past and in the Darwinian world of pop music culture, especially after punk, the immediate past was treated with disdain and often attacked. The present was also highly competitive. Rather than being irrelevant, the Darwinian dinosaurs proved instead to be cultures waiting to reassert themselves – their music, a de facto soundtrack to the era's identity politics.

For the music historian, Jayrem is a rat’s nest of clues to the social and cultural environment and emerging beliefs of young (and not so young) New Zealanders in the rapidly changing times of the 1980s and 1990s. All its records indicate broader communities, which indicate social and cultural activity, which in turn implies stimuli and motivation. The very process of culture being created, from which, personal and group identity is then constructed.

There was also a keen eye and attuned ear on the wider international music picture in the catalogue, although these were not shots in the dark. The music releases were current permeations of an ongoing strand. Heavy metal and hard rock made a fresh start in the early 1980s, and as always, New Zealand musicians responded to the point where Receiver Records LP (UK) collected the best together for Attack From Downunda in 1986.

Jim Moss, Jayrem featured in Wellington City/Cosmo.

We were sending steel to Sheffield. Reggae was always popular in New Zealand. Record shop catalogues of the late 1970s and early 1980s reveal a wide range of Jamaican reggae available. Indigenous reggae as a voice for cultural reassertion was also a distinctive voice of the time. Electronic driven pop music had a sizeable following in New Zealand. Our 1960s generation weren’t finished with music yet either.

Flesh D-Vice's - Flaming Soul EP, issued in 1985

Jayrem Records is still going strong today. A selection of reissue CDs has made in-demand catalogue items available again.