Part III

Analytic Excursus

What was the groove? Rock and roll music was as manufactured as country music had been since the 1930s. As soon as it was first made, it was essentially conservative. One paradigm of popular music of the 1950s is: white cowboy music + black gospel and blues = white rock’n’roll = Elvis Presley.

“A part of the culture were the groovy dancers,” says Peter Williams. “Like cool was a word. It may read well that we were influenced by the black music but ... there was a band called The Saints, Polynesian players, and they related to Sam Cooke. It was the Māori bands that cottoned onto the soul thing ...”

Presley was never a hillbilly, he came from too far south for that, but he did tour country fairs with shows that resembled the white cowboy revues of country musicians such as Hank Williams. It was a music, booze, drugs and women circuit open to any showman. Cowboy music was a manufactured insert to “country music”, a combinatorial of slick studio sounds from Nashville (including the inescapable fiddle lines derived from Appalachian folk music) and the wobblier yodel-type music of the West (which includes the German harmonica, immigrated to Texas, amongst its instrumentation). It was dance music.

“When I started learning guitar,” says Williams, guitarist with Max Merritt’s Meteors, “I actually wanted to be the life of the party; go to a party with my mates and a few birds and strum away at my guitar. The first band I was in was a garage band, we played at a 21st and the first song I sang on stage was ‘Calendar Girl’ – Neil Sedaka – and the Everly Brothers’ ‘Walk Right Back’ ... I wasn’t thinking rock and roll, I was thinking party music ...”

Max Merritt and The Meteors at The Christchurch Teenagers Club, 1958.

Rock and roll shared the radio waves with “that old time religion”, which came from the same places it did. It was the articulation of ordinary conversation about big concerns, the way simple people in empty spaces talk to themselves, a response to emotional vacancy. (In the US, country music and tele-evangelism were becoming the origin of the confessional rhetoric of television talk shows.) Country music comes from the Bible Belt: the realm of fundamental, and/or Christian, values and freedom of expression. It’s complainer’s music about trust and betrayal. Somebody has sinned. There are no judgements, only the redemption that confession brings. It is human, the music says, for a man to be faithless and a woman to be betrayed. But betrayal is so essential to humans, betrayal could be where the deepest happiness comes from.

The music takes for its major themes therefore: sexual infidelity, marriage and adultery. It is a provincial music about lonely houses/motels and dark roads. It was AA music, it was Triple A music too: the background noise of the Age of the Ascendancy of the Automobile. Fast cars, fast rides, fast death. Die young and leave a good-looking corpse. Let life be intense and brief! So, the musical message is that happiness is the quickest and deadliest thrill. Ecstasy may last no longer than the record.

“It was just the grooviness of the song,” says Williams. “Without wanting to be discrediting of Ray Columbus and his band, they tended to be on the sort of ‘cretinous’ level of, you know, give the public what they want. Max did what he wanted to do and gathered in an almost alternative sort of crowd. There was almost no such thing as writing your own material …”

Life should not be submitted to delay by adhering to a moral code (which in any case may be illusory: being female or being young does not guarantee innocence). Everybody is fallible and everyone will fall. That fall/failure is the proof of our frailty, our humanity. The purpose of life is to achieve redemption. The “puritan” heart is aware of sin, for sin and sex makes people the same. The puritan is not necessarily judgemental or inimical to free expression. Sin may make you “guilty as hell” but it’s a necessary prelude to the forgiveness that opens the portals of pearl.

Formally, the music supports a language game, lyrics that delight in puns, parody and mimicry. The message is so elemental it can be repeated endlessly. And yet the message is so basic to our consciousness that we discuss it endlessly too, it is a discussion about good and bad, finally it is about justice. But justice is neither deserved nor earned, rock and roll inherits country music’s emphasis on authority, but not anxiety. And the discussion takes place in public, the personal is only ever exemplary.

Max Merritt could be seen as a template of the rock and roll life.

It was out of all this shellac that New Zealand made its own version of rock and roll. It was not a music that worried too much about what was real and what was not. People stood for something else, their clothes and hair had symbolic roles, people played roles their accoutrements demanded. The musician’s truth lay in the accumulation of his experience. Any accumulation carries a message. Experience was more intense in the city, rock and roll was what happened when country was urbanised.

What made rock and roll different from country, however, was its proximity to African-American music, blues and jazz and hooting and shouting. Rock and roll maintained a racial (and sexual) ambiguity because it was sung and played by whites as though by African-Americans. Rock and roll was a hybrid, a novelty, an exaggeration, a satire, a racial slur (ironies that returned the listener to heightened anxiety).

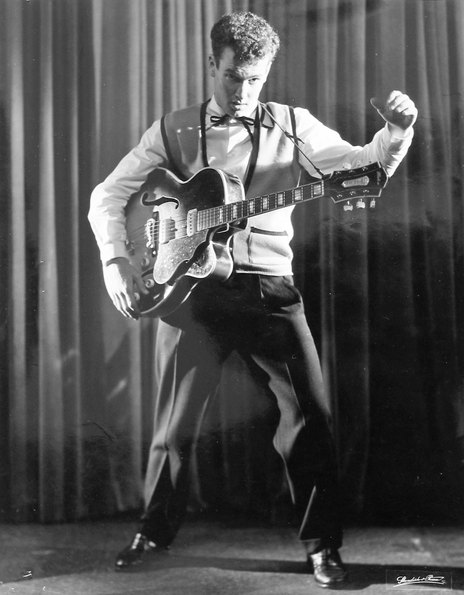

Max Merritt could be seen as a template of the rock and roll life. He starts out in a white sports coat with a bow-tie, the urban cowboy somewhere between lechery and innocence. He tours the country halls in variety shows that are also venues for salvific preachers. But there is anxiety too: before long he wants to be elsewhere. He wants the serious critical attention his experience and fame seem to demand. He becomes self-reflexive, aware that he is making variations, copies and re-representations.

He is an artist.

Max Merritt: late 1950s publicity shot

Part IV

Peter Williams, ex-Meteor: “I used to enjoy the fact that people put themselves out to come and enjoy what I enjoyed. It’s all gone. It’s all fragmented. It’s been manipulated. Back in those days, people flipped the record and heard the B-side, like Them’s ‘Gloria’, and … it’s sadly lost …”

Among the Teenage Club’s assortment of performers was English sailor Tommy Adderley, who sold nifty clothes and men’s after-shave on the docks. Because English ships spent around six weeks loading cargo in New Zealand ports, he became well-known in various towns. After a couple of trips, he jumped ship in Wellington. Max also shared occasional gigs with Martin Winiata, who introduced him to the records of Keely Smith and Louis Prima: “They were real cool!” It wasn’t colour, it was the music. Other entertainers, in later years, were Jim McNaught and the Supersonics, The Howard Morrison Quartet, Tony and the Initials.

1959 continued to be a momentous year for Max. The Teenage Club travelled in two buses down to Dunedin to hear American crooners The Platters in concert, returning at 5.00 am. Once again, the Meteors were among the finalists of the Talent Quest and, once again, they went out on a South Island tour. Also on the tour were The Saints (although managed by King’s rival Bart Ball), The Giants, The Viscounts, Bobby Davis and His Dazzlers and the Harlequin Skiffle Group. One of the most astonishing acts was The Fabulous Balancing Deltics, a group of acrobats who performed in trunks and bathing caps, and were covered in glittery, silver body-paint. They had arrived in Christchurch with the first Hungarian refugees.

Max Merritt and The Christchurch Teenagers Club (promoter Trevor King on the left) welcome Tommy Sands, 1959

But, at 18, the star of the tour – billed as “Canterbury’s king of rock and roll” – was Max Merritt. The Meteors had just recorded a song Max wrote with Teenage Club regular Dick Lefussier called ‘Get A Haircut’ (b/w ‘Dixieland Rock’). They used the 2-track – one for the band, the other for vocals – the 3YA studios, at the request of Dave Van Weede at HMV. On 24 May, Trevor King organised their first concert as headliners at the Theatre Royal. The following month Van Weede wrote to Max about ‘Get A Haircut’: “From advance numbers we have received for it, it would appear it may develop into a hit.”

If there was a “Big Shot” in Christchurch, it was clearly Max Merritt. In September, health authorities used him in a campaign to get kids to take their polio shots. Asked by The Press about vaccination, Max said “Man, I dig that crazy idea.” The launch of his record at Begg’s music shop drew several hundreds of fans filling the store and spilling into the street.

In December, Mabel Howard returned to the Teenage Club as special guest for the Christmas Party. “Today’s youth want noise and ginger and it got both at the club,” she announced. “Some people condemn this rock and roll business because it is a noisy and energetic form of dancing. However, I can tell you, some of the dances I did 50 odd years ago were far hotter work than this.”

The success of the Teenage Club saw imitations sprout in the suburbs. In Addington, in Spencer Street, Father John Coleman began to organise dances too. Father John was a priest with a frustrated musical bent because his Monsignor had told him to sell his drum kit. Now, he started to audition rock and roll bands between baptisms. Although the hall was licensed for 375, there would be over 1,000 people bunched in to listen to Max and the Meteors or to a hot new band led by Ray Columbus. Trevor King had given the young tap-dancer work as the ice-cream boy at the Tivoli while he got a band together. Ray was looking for “girls” but Father John would have up to 60 parish parents patrolling the Spencer Street Hall to keep the venue “safe” for those same girls.

1960 began quietly for Max and the band, at the Floral Festival in Hagley Park. Billy Karaitiana had started as a piano player but, with the departure of Ian Glass, he switched to a 1930s Gibson strung with four strings and played bass. Geoff Cox, the bouncer at the Hibernian Hall, became the rhythm guitarist. In February, HMV’s Dave Van Weede wrote to Trevor King again: “I don’t want to appear in any way to be pushing you along, but I would like to know if Max would be prepared to do another four items …” And that year’s Talent Quest was the biggest yet. Max didn’t win it but, out on the road, he was still the major star.

Trevor always made sure there were photos of the acts on the posters. People wanted to see what the performers looked like. His advance-man in Invercargill was Frank Stapp who worked for New Zealand Railways. Frank would cover the town with posters for what he always said was “the greatest show ever!” His catch-cry was “The game’s still on, Master!” and The Master was his nickname.

Max in Christchurch, late 1950s

The night this tour came to town, he had to watch as the supporting acts were pelted with plums until The Meteors came on. Max then yelled unheard into a microphone but the audience were satisfied. The local paper reported that the crowd moved from “uninhibited bedlam” to being “an audience in raptures”. One of the unfortunate support acts was Vern Scandrett, the son of the Chancery Lane gun-shop proprietor. He was a ventriloquist who worked with a duck doll: Delarno and Duddles, the Duck with the Protein Personality. Later he opened his own magic shop in Chancery Lane and Trevor always used him to entertain backstage when the Vienna Boys Choir were in town. The Choir stayed at the Shirley Lodge; Trevor made sure they had lots of Coca Cola and he always returned to collect the empty bottles.

Laurie Julian’s record store was selling hundreds of records by local artists; the cinemas were showing new “teen-pics” such as Hey, Let’s Twist and Love In A Goldfish Bowl, and Max was driving around town in a Dodge Kingsway. “Rock and roll is just a way of letting off steam,” he told the Christchurch Star. And, after the first rush of youthful freedom, “high” society was looking for ways to reassert its cultural authority. The Canterbury Schools Committees’ Association began the backlash by sending War Picture Library Comics #3 to the Minister of Justice objecting to its violence; the Minister replied with appreciation for their concern. Police brought pressure to bear when a Hereford Street milk bar applied for planning permission to cut down a wall, extending its capacity from 15 to 25. Traffic Superintendent Kellar made “personal observations” and noticed many motorcyclists “of the teddy boy type” gathering on the pavement. When a constable was called to assist, a tussle developed.

The fight went from the milk bar to the pavement to the gutter.

One youth swung frequent blows at the constable. The traffic officer lost his helmet. The fight went from the milk bar to the pavement to the gutter where the youth spat on the constable. The constable called for help from the bystanding crowd of more than 100 on their way to evening theatre sessions. A taxi used to take the youth away had to force its way through a fist-waving, ill-tempered mob. Outside the police station, members of the gang demanded “auditions” with the police but were politely refused. The building permit was refused.

The Aranui speedway too was threatened with removal of its licence if it did not reduce noise considered “obnoxious to the neighbourhood”. Senior police officers reported that special patrols were keeping city pavements “entirely clear”. The “milk bar cowboys, bodgies and widgies” moved out to New Brighton although local shop proprietors said they would not “tolerate hoodlums”. Police shadowed one motorcycle cavalcade around Banks Peninsula for two days.

After a year’s planning, Christchurch made its boldest bid to reclaim its lost youth. In September 1961, various civic groups held a Youth Week, which amounted to two concerts on Monday 11th and Wednesday 13th. Admission was 2/6 and 1/6, with a 3d booking fee. The concert featured Buckett’s Gym Trick Cyclists; the YWCA Ballet Display; the Can-An-Ju Judo Display; and the Girl Guides with a “Māori stick display”. The YWCA presented an “Adventure in Space” in which young Christian men, in different poses, depicted a rocket launcher, a missile and the sorts of life the young Christian men thought might exist on other planets. The ambulance group began their display by asking the smallish audience: “How many of you know the telephone number of the St John’s Ambulance?” Ten of the Boys Brigade used two ladders hinged on a base; their act, poses in various positions, was called Ladder Pyramids. Mayor Manning closed proceedings with the comment that if parents could now see where to send their children for social activities, it would be a godsend for the city. He did not attend the second concert.

Max Merritt and The Meteors 1960 - L to R: Ian Glass, Rod Gibson, Bernie Jones, Max Merritt, Billy Kristian.

Neither did Max. By 1961, the Teenage Club was running three nights a week with the addition of performances at the Hibernian Hall in Barbadoes Street. He had kept the Meteors together and scored big in the South Island with half a dozen singles on HMV: as well as ‘Get A Haircut’, there was ‘Kiss Curl’, ‘Mister Loneliness’, ‘Weekend’, and two instrumentals influenced by English group The Shadows, ‘Cossack’ and ‘Valley of the Sioux’. He was 21 years old and he was preparing to depart. Max had brought in Peter Williams as a singer-guitarist because he was getting worried that his voice, always husky, would give out. In 1962, Max Merritt and the Meteors farewelled their hometown with a final concert, a fund-raiser organised by Trevor King. Even Mayor Manning attended. After it, the band worked their way up through small towns towards Auckland. They spent Christmas Day camped on the beach at Te Whanga, Hawke's Bay.

Two weeks later, they opened the Top Twenty night-club in Durham Lane Auckland. And playing the Shiralee, the Galaxy ... “working for wages, we’d start at seven and work till one in the morning,” says Williams. “You’d play an hour bracket, then they’d play three records, ten minutes off, and then another hour ...”

The band was going somewhere. No one knew where, just somewhere ... A year later they were touring Australia as part of a bill behind Sheb Woolley and his hit, ‘Purple-People Eater’ ... In Christchurch, Trevor King kept busy touring Kenneth McKellar, Basil Brush (a puppet on a broomstick operated by a man in a cardboard box), Acker Bilk, the young Kiri Te Kanawa, and ...

“I had The Underdogs,” King told me. “They were pretty scruffy when they came out with me. They borrowed the boat at the back of the motel in Tauranga, and rowed out, and some millionaire there had a boat out in the harbour. They all climbed aboard it and this fellow had a pair of binoculars at his house, and saw these fellows climbing over his boat so he called the police. So the police went out, and when the boys saw the police coming they all dived in the water. So, the police pulled them out of the water. I had the show on at the Tauranga Town hall that night and the police sergeant rang me: ‘We’ve got a mob of blokes who’re supposed to be in your show. You better come and bail them out, get them out of my police station ...’ The story was in the Herald and their parents in Auckland – one was a lawyer and one was a cop – they all headed down in cars and they all tried to blame me!”

The Queen made Ngaio Marsh a Dame Commander of the British Empire, she granted Frank Stapp the Freedom of the City of Invercargill and she gave Trevor a Service Medal.

Max came back to New Zealand for a national tour with the duo Bill and Boyd. The band was in Queenstown when the Beatles arrived in June 1964. They checked into the same hotel in Dunedin where the Beatles were staying ...

Max Merritt and The Meteors 1965: Jimmy Hill, Peter Williams, Johnny Dick, Max Merritt

“We got to meet them and had breakfast with Malcolm, their tour manager,” recalls Williams. “We saw the show with the best PA in New Zealand, because they used house PAs – in Wellington you couldn’t hear the band at all – but prior to the show they used two of our guys as decoys ... Mike Angland and Johnny Dick ... the kids saw it wasn’t the Beatles and tried to lynch them … they got driven three or four blocks and then they were walking back down the block like they were nobodies again ... Johnny Devlin was on that tour with the Beatles, I always remember talking to him as he was ironing his leather suit …”

Bruno Lawrence played with the band for a while, “a great drummer, a really nice R&B feel, the band could get a real good groove ...” Another drummer was from the old Columbus band, Jimmy Hill. In 1971, Max took a reformed Meteors to England. They were most popular up in the desolate north for Max always played the music of the margins. But, Max later confessed: “It seemed we were playing pubs forever; in your youth everything seems to drag on.” He never made it to the wealthy play-offs in the mainstream, never became Pop. Maybe he was too sincere. Pop relies on irony, it celebrates its birth by many hands in factory conditions. Rock and roll requires three minutes of sincerity but Pop never presents more than ambivalence. Success in Pop is measured in “units”, huge sales that support the economy of consumption, even national export-drives. Pop recycles within its own economy too, creating nostalgia by recycling itself instantly. Pop, it came to be said, eats itself.

“Martin Winiata played a bit of rock and roll and ballads. He actually helped to teach Max Merritt, in the early stages, the guitar. He’s passed on, though I saw him when I was on tour with the Vienna Boys Choir. In Taupo. We pulled up there for lunch and he came out and ... and, I thought what a come down, you know ...”

In 1977, Max, exhausted by touring black holes in the economic graveyards of Great Britain, broke up the last version of his Meteors. He went to Los Angeles ... he still lives there and sometimes telephones Trevor, his manager for those first magic years.

“We never had a contract,” says Trevor. “It was a gentleman’s agreement. And I was with him for seven years. The deal was that I took 10 percent of the dances and concerts. When we did theatre shows we did 50-50, after all expenses were done. He paid the band. He wasn’t a businessman. I got all the receipts and the rental of the hall, and put them on the table. He’d always go back to his place for supper (his mother was a great one for making cheese scones). Never had a drink there. They were teetotallers.”

Some nights in Spreydon, King gets his scrapbooks out ... “it’s part of your life, you know,” he says ... and sometimes he thinks he’s still alive in that era, travelling round town at night with a bucket of paste and a pile of show posters on his bicycle. A favourite spot for bill-sticking was the old fence around the Addington Showgrounds. One night the heavy hand of the law loomed up from the shadows ...

“Hello, hello, hello,” said the constable, “have you got authority to put those on there?” “Yes,” said King, and, without missing a beat: “Would you like to go see the show one night? Here’s two tickets ...”

In 1998 he was dressed as he always was, in grey slacks, blazer and shirt-and-tie: a respectable man working at his trade. The constable held the paste-pot while he finished sticking-up his pile of posters. But that was then and, says King, “... things have changed now ...”

--

Postscript: Trevor King QSM died of a heart attack aged 87 on 22 February 2011, the day of the second major Christchurch earthquake. In his room at the resthome, he was surrounded by his scrapbooks and memorabilia. The Press obituary can be read here.

Trevor King, left, road manager of the Showtime Spectacular tour of 1961, with Toni Williams (in shades) and Howard Morrison. On the right is Brian Richards. - Trevor King Collection

--

This essay was presented while Alan Brunton was Writer in Residence at the University of Canterbury 1998 as part of the seminar arranged by Dr John Newton called “Making Histories”. In his typescript he thanked the English Department “for their various kind invitations. For the essay, my particular thanks are due to: Trevor King, Gordon Spittle, Jackie Waylen, Peter Williams.” Hey Bird is published with the permission of Alan Brunton's literary executors.

Sources: Trevor King interview, 29 July 1998; Peter Williams interview, 28 July 1998; Stranded In Paradise, by John Dix (Paradise Publications, 1988); Counting the Beat, by Gordon Spittle (GP Publications, 1997); for discographies and band members, see: The Fax About Max, by Paul McHenry (Golden Square, 1996).

--

Hey Bird: part one – Trevor King and the birth of Christchurch rock’n’roll