Over five decades Fane Flaws has been one of the most prolific creative forces in New Zealand music. Perhaps best known as the founder of 1980s pop wonders The Crocodiles and co-writer of their biggest hit ‘Tears’, he also brought his talents to bands from BLERTA to Spats, directed numerous music videos, and was responsible for the memorable animated title sequence for Radio With Pictures. Also, with Peter Dasent and Arthur Baysting, he created the children’s book, album and stage show The Underwatermelon Man. Curious to know more about the origins of Fane’s unique musical aesthetic and circuitous career, I spent a couple of hours in conversation with him during the 2020 lockdown. We never reached the end of the story, but we made a start.

You say 1967 was a crucial year for you. Why is that?

I was on a radio show not long ago and they said, “Why don’t you do a show about your influences?” And I came up with the idea – because I’ve got this thing about 1967 being the greatest year in music – well why don’t I just concentrate on ’67? I did a show that had 30 songs. I didn’t play them all, I only played bits of them, but I said “I’m trying to paint a picture of what it was like to be 16 and 1967. This is what was going on in the world.”

Fane Flaws performing with The Bend at Eggscentric Cafe, Whitianga, December 2015. - Den Rob

My opening track was ‘For the Benefit of Mr. Kite’. I said, “I’m playing this because it was a fucking circus, you know?” And then I played ‘Abba Zabba’ from Captain Beefheart’s Safe As Milk, ‘Astronomy Domine’ off the first Pink Floyd album, ‘Third Stone From The Sun’ off Are You Experienced?, stuff from the Doors’ first and second albums. [Cream’s] Disraeli Gears came out that year and I said, “Here’s Clapton, basically playing the blues on a pop song. And you know Eric Clapton started off in the Yardbirds and then went to John Mayall? Well, let’s have a listen to the Yardbirds and see what they were doing at that point”. And I played ‘Over Under Sideways Down’, as it’s Jeff Beck and Jimmy Page. Then I played Hendrix and said, “So while we’re on guitar heroes, here’s Otis Rush from Chicago/The Blues/Today, volume two, and all of these guitar players that we’ve just heard, they were all influenced by Otis Rush, you can hear it. I played the Kinks’ ‘Waterloo Sunset’ and ‘I Can See For Miles’ by the Who and Aretha ‘I Never Loved a Man’ and James Brown – well, he invented funk – here’s ‘Cold Sweat’. This is how good this year is. I played Wilson Pickett, the Temptations, Moby Grape, Grateful Dead, the Beach Boys’ ‘Good Vibrations’. There have been a few things since – The Band’s Big Pink [which] didn’t come out until ’68, and there’s been Bowie and Prince and Wilco – but my main influences were all those people in ’67.

So where were you that year when you were hearing all of this?

I was in Wellington College, fifth form, and my mate Ian Leva – who was this Samoan boy who was adopted – his brother had Are You Experienced? and we used to go to his little room out the back of their house in Abel Smith Street and play vinyl. And I got Are You Experienced?, Fresh Cream, and John Mayall and the Bluesbreakers, the album with the Beano cover. I bought them all in the same week from Begg’s. And then Sgt. Pepper’s and Magical Mystery Tour! And what I loved about it was that none of the bands are trying to sound like each other. They’re all trying to be original, which is the complete opposite of modern pop music. What a great idea! Try and be really original. Try and outdo the other bastards, you know, do something that they go “Whoa, what’s this?”

The rules hadn’t been set yet.

It was all one radio station as well. It wasn’t like, “You’ve got to do it like this and then you get played on the hip hop station”. I think that was the death of creative music, formatting. Fucking terrible.

What live music were you hearing at that time?

I remember going to a bloody garage in Tawa with a couple of mates and there was a band in this garage playing ‘Fire’. It was Phil Pritchard on guitar [later in Highway] and a drummer called Bill Brown whose father was a drummer and they sounded completely amazing, and I was like, yeah! This just blew me away really.

Fane Flaws, left, with BLERTA at the University of NSW, Sydney. - Fane Flaws Collection

Did you have a guitar yet?

No, I got a guitar when I passed School Certificate, which would have been the end of that year. My mother gave me £25. There was a guy in our Bible class in Johnsonville at St Columbus Presbyterian Church by the name of Michael Johnson and he had an acoustic guitar which he had put a pickup on, and built a little 12-watt amplifier in a radio cabinet, and he played Shadows tunes with a real mellow, quite lovely tone. I bought it off him for £25. I didn’t have a clue how to play it. The first thing I learned was ‘Tin Soldier’ by the Small Faces. It was about the only cover I ever learned. After that I just gave up on covers and started trying to write songs. I was terrible at working out covers. To this day I’m still not very good at it.

And did you start playing with other people straight away or were you just sitting in your bedroom?

It wasn’t until design school that I started playing. I ended up in Harry Hood’s Band, Paul Clark’s jug band. Ian MacDougall, who was my mate at design school, lived in Khandallah and had this downstairs flat at the family home and I used to go there and stay on Saturday nights. We would take acid and his mother would bring us cups of tea! We had slide projectors with oil lights and slides and everything all set up going. The whole thing was like the Fillmore East. Our three albums were really Safe as Milk, Hot Rats by Frank Zappa, and Jethro Tull’s Stand Up. And Mrs McDougall would come down and knock on the door with a cup of tea and we’d be lying on the sofa, stereo as loud as possible, unbelievably stoned. At about five o’clock in the morning we’d go for a walk to Khandallah Pool and we’d sit up on this chair above the pool on the hill and watch the neighbourhood wake up. People would come out to get their milk in their dressing gowns and get the paper. It was like watching some completely strange little movie. We had Zappa’s suburban thing going in our heads. But Ian said to me, “Andrew Delahunty is in this jug band and is leaving and they’re looking for a guitar player. Do you want to join?” I said, “Whatever. I love jug band music.” And he said, “Well, Andrew will show you the songs but he probably won’t even talk to you.” So, I went, and he showed me the songs and he pretty much didn’t talk to me, just grunted a bit. Long hair, extremely cool. Onslow. You know we looked on in amazement at these people from Onslow College like Andrew and Chris Seresin and Simon Morris and all the rest of these good musicians playing really interesting music.

Harry Hood’s Band was my first band. Vic Singe played the tuba but he couldn’t really play, he just blew it and made noises. Paul Clark was the singer and played guitar, Pete Olson was the banjo player, guitar and banjo, and there was a guy called Alan who had been in the Band of Hope and played washboard. We had a giant old hearse, a great big Cadillac hearse, that was the band wagon. And we were dressing up wearing tails and top hats and all that sort of shit. We used to play a lot with Highway at Lucifer’s or the Oracle. Highway really liked us and we would always be opening for Highway. So I got to see Highway all the time. I had a year of watching Highway and going, wow. Absolutely amazing. Phil Pritchard on guitar. Such a genius band, so tight.Poor old Jim Lawrie wasn’t allowed to play any fills, just had to play the fucking beat. That was a sort of lesson to me, the way that the bass drum and bass guitar knitted. I love that band. I loved that music. I remember playing a gig at the Paramount Theatre, I think with Highway and Mammal.

BLERTA, 1973. Chris Seresin, Greg Taylor, Fane Flaws, Ian Watkin, Kemp Tuirirangi, Bruno Lawrence. - The Dominion Post Collection, Alexander Turnbull Library

So that inspired you to go electric?

Well, I heard that Patrick Bleakley had an electric bass. We were Johnsonville boys, so I started playing with Patrick and then hanging out at Wayne Sampson’s flat in Percival Street. So it was the Johnsonville boys really, me and Patrick and Wayne. And then we got Wayne’s brother Lawrence involved, and Andrew Delahunty. Wayne and Lawrence were both on drums, we had two drummers. They only knew one beat, that was the problem. Lindy Boyd-Wilson was involved. It was pretty incongruous. She sang Leonard Cohen songs with an acoustic guitar. And Cass Pauley, this girl from Gisborne who sang like Janis Joplin. She was very quiet and very shy and then she would open her mouth and out would come this unbelievable roar! We created a piece of bloody art-prog rock, probably the most horrible thing you ever heard. It was seven-part opus, which went through the colours of the spectrum, so it had a light show with it and we took it to Auckland and played it under the name Patrick. I thought “Thank God nobody ever heard that performance,” because it would have been the worst excesses that you could possibly imagine. But the first time I met Mike Chunn, when we were talking to him about managing the Crocodiles, he came up to me and he said: “Patrick. Auckland University Arts Festival 1971. Unbelievable.” And I’m going “Really?” So he liked it.

How long did the band Patrick last?

Well, we kept changing the name. The one thing I remember about that band is my idea of an arrangement of ‘Summertime’, because Cass could sing it like Janis and Andrew Delahunty played the flute on it. Andrew and I were into Traffic’s John Barleycorn Must Die so he was playing the flute. But then we said, we can’t be called Patrick, you know, it’s not very cool. Let’s have a band meeting, what shall we call the band? And Wayne Sampson goes, “How about Wayne and the Other Guys?” And we all looked at each other and go “That’s really good. It’s cool. That’s it.” And Wayne goes “I’m joking. You can’t call it that. You can’t!” and I go “We’re definitely going to call it that.” We did fuck-all gigs actually, apart from that big thing in Auckland which we worked on for about six months.

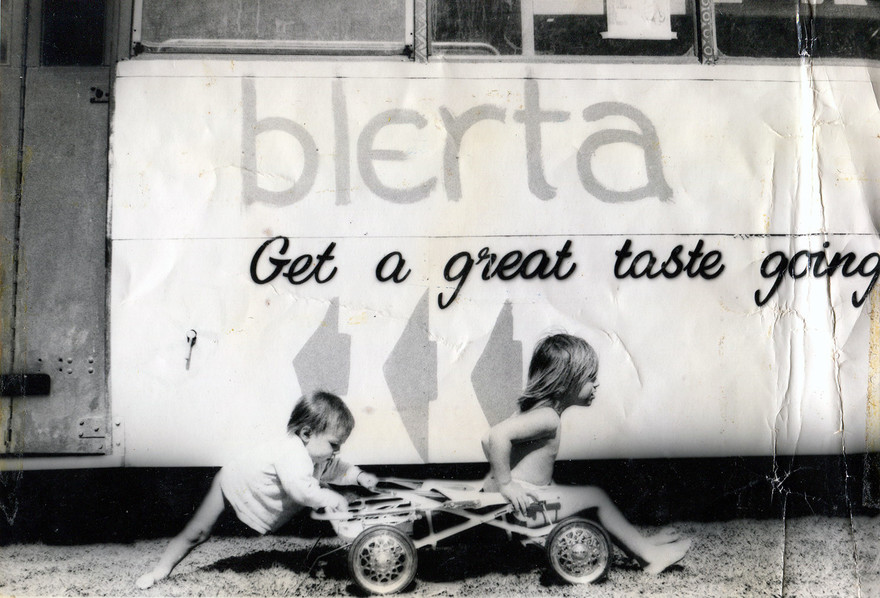

BLERTA kids, c. 1971. - Alan Moon Collection

After that, I was living in Roseneath and the Patrick band was rehearsing up Holloway Road at the end of Aro Street and had a sax player called Peter someone-or-other, and Greg Taylor on saxophone as well, we had expanded for our art rock, we needed some horns and things. But BLERTA had come to town. They had done the first BLERTA tour and before the second one we heard Bruno Lawrence was auditioning musicians at some place up Tory Street, and we all went along – me and Patrick and a few of us, and it became very evident that Patrick was going to be picked as the bass player and Greg Taylor was going to get a job in the horn section. And there was no way I was getting a job doing anything! And that’s when I ended up thinking, fuck, I’m gonna miss out here unless I can talk my way into this. So I told Bruno I had a wizard’s act, because I knew that they did a kids’ show. I ended up going to the Union Hall a couple of Saturday nights later where they were playing, and at the end of the gig they were loading up the bus and I said to Bruno “Where are you guys going?” “We’re going to Mahia.” I said, “Can I come?” He said, “We’ll if you get on the bus you’ll probably come.” I went “Can I bring my guitar?”

BLERTA with Fane Flaws on the roof and Bruno on drums - Fane Flaws collection

And he’s like, oh fuck, whatever. So, I got in my van and drove all the way back to Roseneath, went down 199 steps to my flat, came up with my amplifier, a Marshall 50 that nearly killed me, then went back down and got the guitar, got in the van and rode up to the uni just as Ian Miles was closing the back door of the bus. And I said, “Hey, mate, please can you fit these in? Bruno said it’s okay if I come.” And he looked at me and went, “Ah fuck, I’ll have to repack it.” Anyway, that’s what happened. I got on the bus. And there was Ian Watkin, Tony Barry, Patrick, Greg, Bruno and Veronica Lawrence, Chaz Burke-Kennedy, George Barris. And I ended up on this bus with these people and nothing other than the fact that I was supposed to have this wizard’s act. All I had was an old dressing gown made out of some art deco curtains with a couple of lightning bolts on it that my mother made for me, and I had long hair and a beard, so I looked like a wizard.

We're off to see the Wizard: Fane Flaws with BLERTA. - Fane Flaws Collection

At Mahia we stayed the night on the beach and then we went to Wairoa to this marae and during the day we set up in the hall. I said to Bruno, “I’ve got a couple of tunes” and he said, “Okay, play them” so I played these couple of sort of Zappa-y instrumentals that I’d written, a primitive man’s attempt at making a Zappa tune. He said to Chaz Burke-Kennedy “What do you think?” and Chaz Burke-Kennedy said, “Sounds like he should write them and we should play them.” So I don’t think I played with the band at all that night. But I mean, it was like, “You’re on the bus and you’ve got a couple of tunes, so we’ll learn them,” so that was like a vote of confidence.

Fane Flaws with two children from the BLERTA extended family. - Alan Moon Collection

Corben Simpson didn’t want to know. He said, “You can’t have that fucking guy in the band. He can’t even fucking tune his guitar, he can’t play, he can’t sing!” But Bruno was like, relax Corben, you just sing and play and be the star and I’ll worry about him. And I suppose he just nurtured me in a way. He just gave me a bit of confidence, keep doing what you’re doing, learn how to tune your guitar and things like that, and we’ll see what happens.

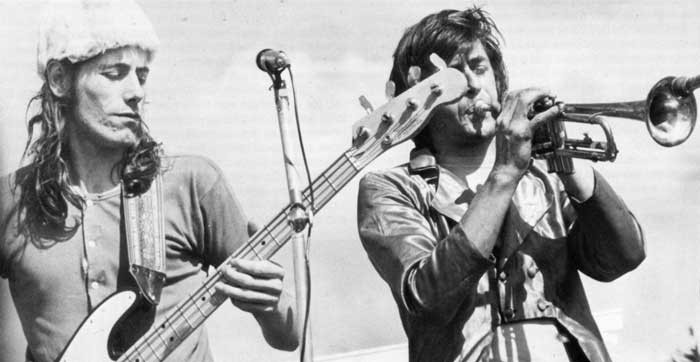

Corben Simpson and Geoff Murphy with BLERTA. - Photo by Helen Whiteford

My Bruno history is interesting, because there was a huge thing that happened to me when I was 13 years old. I went to a dance at the Khandallah Town Hall, my first dance with a live band. The band was Max Merritt and the Meteors, just a hot R&B band. And they came out in these suits and on the left of the stage was Billy Kristian with his pear-shaped Vox bass. And on the right of a stage is a guitar player, then Max. But in the middle is Bruno. And unlike any drummer I’d ever seen on TV, he had his bass drum on the very front apron of the stage, so he was right in the middle and he wasn’t up the back like Ringo, mate. Right up the front, and you couldn’t take your eyes off him. He drummed like a wild animal and he was like the star of the show, basically. As teenagers we danced and did our thing. And I just kept looking at this guy and wondering, what is he doing? What is he on? What is this noise he’s making? I’m gonna have to figure out how to do that, you know? So it was a huge thing.

Bruno Lawrence, c. 1971. - Alan Moon Collection

And then I met him later when I was about 18, coming out of a Fellini movie at the Lido one Sunday night, going to the phone booth across the road to ring my father to come and pick me up and take me home. And there is this guy lurking behind Bond Street, up against the wall behind the phone booth. He’s got a dark-blue navy greatcoat on with the fucking collar up, is completely bald but he’s got great big mutton chop sideburns. And he goes “You got a fag mate?” And then I realised, well that’s Bruno because I’d seen him on TV by then. And I just said, no man, no, I don’t smoke. So that was my second run in with Bruno. And then the third one was turning up to that those auditions.

Eventually he fired me from BLERTA. I had a bit of an indiscretion. Basically I fell in love with his wife. And he was such a bloody root-bag that, I don’t know … But the night that he twigged, I’d actually written her a love song and we were playing it in the band. And one night we were playing in Palmerston North, at Massey [University], and I looked around in the middle of that song and looked at him and he looked at me and I went, “Oh, I think the game is up.” After the gig we had this huge fight. To his credit, he didn’t hit me. Instead of hitting me he smashed his drum kit. Picked it up and threw it against the bus. And then we had a band meeting as to what should happen and Geoff Murphy said, “Well it’s obvious he can’t be in the band anymore,” and Rick Bryant drove me to a house in Palmerston North. He said, this is a crash pad, just go and sleep on the floor. And I went into this house in the middle of the night, didn’t see anyone. The next morning I hitchhiked to Wellington. And that was the beginning of my new life.

I ended up in a flat in Fairlie Terrace with Andrew Delahunty and we started playing with Paul Davies and Patrick again and ended up having a band, The Hot Club de Chez Paree, I think it was called. We played at the [folk club] Chez Paree a few times anyway, trying to play Django [Reinhardt] songs, Billie Holiday songs, and Little Feat. I remember we did ‘Texas Rose Café’ one night and Richard Kennedy was in the audience. He said, “I can’t believe you attempted to play that song” – attempted being the key word in the sentence!

I had all these songs I’d written, and I had just inherited some money because my great aunt had died and left me two grand. That’s when I went to Delbrook studio to record. The Delbrook demos were actually really good – well, parts of them are good. I’m not very good. There’s two rhythm sections, Mark Hornibrook and Kerry Jacobson was one rhythm section, and Patrick Bleakley and Chris Fox was the other. And Tony Backhouse did all the vocal arrangements. Kerry’s playing is remarkable, and Mark’s is completely astounding. I mean, as a funk rhythm section they’re as good as anything in the world. There’s ‘Frostbite’ and ‘Vultures’ and there’s another one called ‘The Blood Protection Company Shuffle’ about buying mosquito coils. And the bass playing and the drumming on them – it’s just like, how did I end up with James Jamerson and Bernard Purdie on my shitty demos in a Tawa basement?

So that was another chapter. I ended up with 15 or 18 songs recorded, which made me think, all these songs are good, which ended up making Spats happen, in ’77 I think.

Spats recording 'New Wave Goodbye' at Harlequin Studio, Mt Eden Rd, Auckland 1977. L-R: Patrick Bleakley, Michael Knapp, Fane Flaws, Tony Backhouse and Peter Dasent. - Courtesy of Fane Flaws and Michael Knapp

Which brought you together with Bruno again.

He was the first drummer in Spats, and then he was the first drummer in the Crocodiles. And eventually I had to fire him from the Crocodiles. It was like this cyclic thing.

You are finishing stuff now, in 2020, which was started anything up to 30 years ago. Where did the process get held up? It wasn’t meant to take that long, was it?

Well with the Sam Hunt album (We Disappear) it wasn’t even an album, it was only six tracks – this was in 1987. We were about to mix and Paul Radcliffe, the engineer, got an ear infection and couldn’t hear anything, so he went home. Then I got a grant from somewhere to finish it, to mix it. And then my house was about to be sold out from under me by the bank, you know, because at that point mortgages were like, you had one at 22.5% and one at 25% and staying alive was nearly impossible because I didn’t have a job. And I spent the money on the house rather than the record, to save the house. And then the tapes got lost for 25 years or something. No one knew where they were and we couldn’t find them. We just kept working on new stuff. Then one day Peter found them in the fucking archives, in the vault. “What is it?” “It’s the Sam Hunt recordings.” And we had a listen and thought, shit these are really good, we have to finish them. That was about five years ago so that’s what happened.

Peter Dasent, Tony Backhouse, Andrew Gladstone, Fane Flaws – The Bend at Eggscentric Cafe, Whitianga, December 2015. - Den Rob

Then the other ones – every few years we’d have a session. Like we recorded the Underwatermelon Man songs and then we’d go “That was really good fun, we should record some of these other songs we’ve been writing,” and we’ve had about three or four really good sessions where we’ve just gone for two days to Sydney, me and Peter Dasent and Tony Backhouse, just go into the studio with Jonathan Zwartz and Hamish Stuart because it’s so fucking quick because they’re so used to it, they do it every day you know. So you go in there and you get 18 songs down in two days, and then we’ve all ended up with the same gear, with Logic, so I can put some guitar on, send it to Tony and he can put whatever he wants to put, and Peter can do this and that, so we can all work on those. I sort of edit it up – that’s too long, or that fucking bridge is useless, we need a new one or there should be a stop there, that sort of shit. And you can do that in your editing in your software. You don’t have to go back and record a new rhythm track.

There’s enough for another album, and then there’s the other kids’ album, The Boy With the Flaming Hair. In fact, there’s probably enough for two. There’s at least 32 tracks and I keep writing the fucking things. I don’t know what’s going on. They just keep popping out. So I send them to Peter. I’m just doing one to send out today called ‘The Unicorn’ about a dodgy guy who’s got this horse in the backyard with a plastic horn and he’s trying to sell it as a unicorn. And there’s this other dodgy guy visiting and they’re having an argument about it and this guy’s got a yeti with him. And then there’s this other one …

--

Read more: Fane Flaws Underwatermelon Man

Watch more: Fane Flaws On Screen