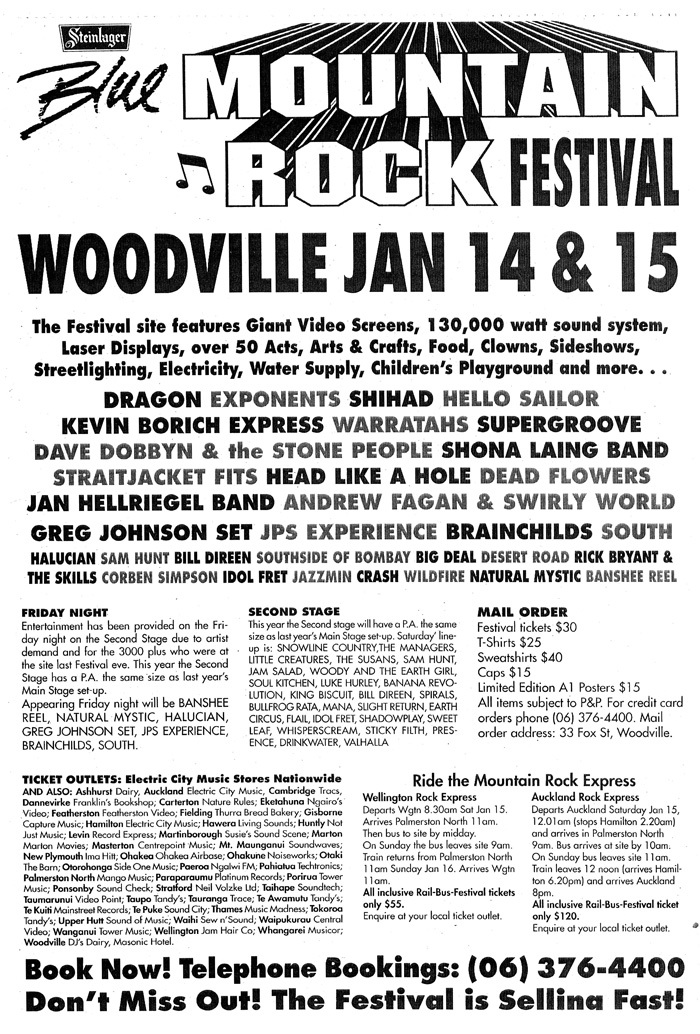

- Photo by Scruff

Here was a man in the corner howling like a banshee. A tattooed photographer was encouraging a couple, who needed no encouraging at all, to get physical on a table top. There was a persuasive pair of people circling the place soliciting samples and autographs for a celebrity body-hair collection. And that was only backstage. Out front where the real people were, it was only slightly less crazy.

Yes, despite the fact that the calendar insisted that it was 1994, this was a rock festival and rock festivals always were giant psychotic encounter sessions. Apparently little had changed.

No one had attempted anything as fatuous and foolish as a rock festival since 1984, when Sweetwaters ended after five years.

The psychosis had set in nicely on the first day of Mountain Rock III, a good excuse for a party that had been launched one wet January weekend back in 1992. No one had attempted anything as fatuous and foolish as a rock festival since 1984, when Sweetwaters ended after five years.

The thievery and the madness had all become too much for the crowds by then, and despite a bill that boasted a seductive line-up of Talking Heads, Eurythmics, Pretenders and the awful Simple Minds, that last Sweetwaters didn't pull the people or the profit. The organisers scattered for the hills and the hidden bank accounts, the rock critics relaxed and the few hippies left standing went back to their headband weaving.

A few years on, a pair of those terrible creatures, would-be promoters, attempted to revive the rockfest beast. They called theirs Neon Picnic, but they ended up several sandwiches short of the picnic and never quite managed to switch the power on. And that, some of us decided, was that — the end of the rock festival, a ludicrous legend that began back at the dawn of time with a cliché-in-the-making called Woodstock. Back then, some people with more beads than sense actually thought music might change the world.

The world went on changing anyway, with rock and roll along as a soundtrack quickly running out of new ideas. Pop had long since eaten itself, regurgitated and swallowed itself all over again. And in the midst of all the 90s nostalgia, it was only a matter of time before a shadow blocked out the sun and, splat, down came a rock festival.

I didn’t really notice it at first. That was hardly surprising, given that they held the debut Mountain Rock down in a field near Woodville, which is through the Manawatu Gorge from Palmerston North, a town with something of the charm of Invercargill. But Sam Hunt had come back from Mountain Rock I impressed. Then Rick Bryant, the soul singer, played Mountain Rock II and said it was a bit of a belter — an all-Kiwi line-up attended by a crowd close to 15,000 (10 times the population of Woodville).

By 1994, Mountain Rock was looking like a monster that had to be looked at more closely. Not only was a rock festival upon the land, but a scourge of nouveau-hippiedom was also upon us. Flares were standard in jeans shops and there were clogs and platforms everywhere. There had been alarming sightings of muslin on High Street. “Hippie” was in transition from insult to compliment. It was getting scary out there.

I remembered Sweetwaters. Five years featuring three days of drug and alcohol-assisted madness. Great music (apart from Simple Minds), but too many near-death experiences. I lost count of the times I fell asleep driving north, ruined at 4am, to squirt out a review for the Auckland Star before heading back down for the next day’s madness.

Corben Simpson and Sonny Day - Photo by Scruff

The one year I was allowed a motel near the festival, I staggered in at dawn to find an assortment of local bands asleep in the living room and my apprentice in the arms of her boyfriend in my bed. I assumed they didn’t want me to join them and crawled off to sleep in the kitchen which was so small I had to put my feet in the oven. I briefly considered putting my head in.

I remembered the last moments of the last Sweetwaters vividly. It rang in my memory like an alarm bell. Lurching about behind the massive stage, I’d found my way into the caravan of Flying Nun Records, where the entertainment options heavily featured Johnny Walker Black Label and hash. At the insistence of the good Nuns, I glugged down several large tumblers of Black Label and arfed up huge lungfuls of killer hash through a bottomless two-litre Coke bottle.

In the distance I heard the mighty clang of Aussie metal band Rose Tattoo, the last band on the bill. “Back to work,” I gasped at the caravan and fell out the door. It was only when I was in the warm embrace of the crowd that I realised all was not well. The soundman had taken the opportunity to push the massive sound system to the top of the Richter Scale and the noise was so extraordinary I felt cells flying off me.

Then the hash and the Scotch, the hundred cans of beer and the nasty speed from earlier on formed a fist in the pit of my stomach and surged up to punch the top out of my skull. I lurched through the denim and leather crowd as a deep personal darkness closed in on me and I collapsed in the shadows out on the edge of the mob, hoping that someone I knew would find my body and organise a decent burial.

Instead, my flickering eyes widened in horror as, out of the darkness, a huge biker materialised, stalked towards me, upzipped and unravelled what appeared to be a fire hose and pissed on my leg.

I don’t know if he even saw me lying there, but from my point of view it was a very bad scene and I worried later about what might happen the next time. But there wasn’t a next time. Well, not until Mountain Rock III popped up.

Time to go back to hell, I thought, and persuaded Metro magazine to fund my death trip in exchange for the right to print my last words.

With the Mountain Rock organisers sticking to their all-Kiwi line-up, expanding the event to two days, predicting a crowd of 30,000 and (for the first time) pitching to a previously disdainful Auckland audience, it was all looking very serious. Time to go back to hell, I thought, and persuaded Metro magazine to fund my death trip in exchange for the right to print my last words.

It looked serious in a different sort of way when I arrived at the end of a long road from Auckland. Ah, nostalgia ... cops, hippies, hoons and gangs were everywhere. It was Westie World on a farm in the middle of nowhere. But there were certain practical matters to be taken care of first. I had to find my photographer. His name was Scruff and he enjoyed some natural advantages when it came to this sort of high-impact social situation. I knew he was a capable photographer. But, more importantly, I also knew he was fearless.

Also, people tended not to say no to Scruff. He wasn’t a heavy guy, he just looked that way, even in a dress. He was wearing one when I found him. A green number that nicely set off the bare-chested look Scruff favoured, but he had the chest for it. There was already quite a crowd in, he said, along with just about every gang in the land, including a bunch of outlaws called the Nomads, guys so red-eyed and crazy that even the other gangs hated them.

At the other end of the social scale were the gypsy housetruckers, who Scruff had been travelling the byways with and who we found in their villas on wheels gathered in what may have been a protective circle on a hill above the festival’s second stage. They were there direct from a gypsy convention in Tauranga (of all places). Scruff said they “looked after” him there and they certainly all seemed to know him. Must have been the dress.

A gypsy family invited us to dinner with them. Rice and vege stew. They were nice people, good cooks and there was even a passable Bob Marley covers band providing music from the nearby stage. Maybe the hippie thing wasn't such a shaky concept after all. Good God, what was I saying?

We drifted through the crowd, attracting the sort of attention to be expected when you were carrying a tattooed, transvestite biker lookalike as crew. There must have been six or eight thousand people in by then and the dusty approach road was full of new pilgrims. There were stalls — including a massive bar selling sponsor Steinlager’s products by the box — arranged into two folksy streets. The food was the worst sort. It was hotdog city. No wonder the gypsies were into home cooking.

There were a lot more black jeans than blue and, socially, the locals were a cross-section of New Zealand society — with the mainstream mostly missing. There were already some seriously-out-of-it people there, women especially, lurching through the crowd, falling over. And temporary gang compounds, some with bikes neatly arranged outside. Things seemed relaxed, though.

It was time to visit the backstage world. The bar wasn’t set up yet back there, but some people were. Sam was behind the back-of-stage compound in a blue caravan with no power and two candles. He was happy. Scruff’s home-away-from-home was in the vicinity too, a big green bus, a wooden number of indeterminate age. It took him a couple of weeks to get here from Auckland — what with the stop-off at the gypsy convention and everything — and on arrival the bus promptly dropped its gearbox and blew a gasket. It looked like Scruff might have to take up farming after all the music was over.

From a dark corner in the green bus, Scruff produced a bottle of something he called White Lightning, a double-distilled whisky he got “from a gypsy”. One of the housetruckers brewed it up in a still he carried onboard. It sold at $30 for a family-sized lemonade bottle full.

When we regained the power of speech, Scruff proudly produced a clipping from the Bay of Plenty Times heavily featuring a picture of him and Tim Finn and an interview with each of them. Scruff’s was twice the length of Tim’s, though tragically he was referred to throughout as “Scruffie”.

“Scruffie drinks more herbal tea than alcohol these days,” I read as the subject (who had a past life in rock-star personal security) passed me another tumbler of gypsy rocket fuel. “C’mon Scruffie, let’s go see if we can still walk.” We could and that old-fashioned-sounding band bamming it out from the second stage was Auckland’s Greg Johnson Set, Johnson still not sounding like the natural-born lead singer he should have sounded like that far into his career. Out in the gathering darkness in one of the camping and parking areas, we found a guy who seemed, at first, to be attempting sexual congress with a car. He was, in fact, washing it. He was also utterly legless. “They told me to wash it,” he screamed at us. “And it isn’t even mine.”

Back in the relative sanity of the backstage world, various members of the headline act Dragon were dragging themselves into a soundcheck for the following night's set. Dragon left New Zealand in the mid-70s, genuine rock and roll pirates led by the very tall Hunter brothers from Taumarunui, singer Marc and bass player Todd.

In the ensuing 20 years, they’d had more ups and downs, departures, deaths (drummer Neil Storey, keyboardist Paul Hewson), splits, reformations (not religious) and weight gains than any other half-dozen bands put together. That particular get-together-again for Mountain Rock was so new that their soundcheck was actually a rehearsal, Todd (now 42) packing a lot of beef and grey hair, and 40-year-old Marc, waist wide and hair short and dyed with what appeared to be a peroxide-white variation, disconsolately running his vocals at a low level as an unwanted crowd gathered in front of the massive stage.

The author with Sam Hunt

Backstage earlier, the famously arrogant Marc had run into Rick Bryant, an old friend from the old days. “Did someone die?” he asked Bryant, who was dressed in his customary black sweatshirt and matching pants. Over on the second stage, Auckland enigmatic indie types Jean-Paul Sartre Experience were down slow with the crowd.

Not on top form anyway, their bass-heavy atmospheric rock sounded soupy and this crowd didn't want soup. It wanted riffs.

Out of sound and sight over the hill, Dragon were going through the motions and Marc, whose last album involved jazz standards, moved like a large old man. Pity we couldn’t get some of Scruff’s White Lightning up to him. It could only help.

We headed back to the gypsy encampment as The Brainchilds, a brainy Wellington band, played an earnest unsexy set that only livened up when singer Janet Roddick picked up her trombone. We said hello to a glassblower housetrucker and visited a tattooist housetrucker called Doug, his lady and friends. Nice people, average tattoos.

There would be unhappy campers over the hills at Mountain Rock, hangovers and dodgy weather being a bad combination.

Friday night rolled on and not everyone was friendly, but the hippies were. About 1am, I headed back over the top of the Tararuas into the clouds and down again to the flat-as-a-flounder Palmerston North where a lot of the bands were being put up at the Quality Inn, along with a bunch of stock car drivers. The potential for combustible social activities should have been high, but all seemed quiet.

Next morning when I gingerly peeled the curtains back, Palmy North was being whipped by a damp wind under a big grey sky. There would be unhappy campers over the hills at Mountain Rock, hangovers and dodgy weather being a bad combination in the middle of nowhere. The imposing figure of actor Ian Watkin, who was one of the festival’s comperes, dominated the hotel foyer, along with the shorter but still imposing figure of Rick Bryant. Add in the imposing figures of one of the Mountain Rock organisers, Daniel Keighley, and those huge Hunter brothers, plus their little (but not that little) brother Ross, who was doing roadie duties, and the place had a surfeit of imposing figures. It was no place for a weed like me.

Rick Bryant and band - Photo by Scruff

I skulked off to the dining room where they were playing “Johnny B Goode” at a discreet volume and the toast might be the only decent food I got all day. Despite the rumours about noses, rock and roll ran on its stomach. Hence, I guess, all those imposing figures.

“At least you’re looking a bit more like a bloke,” I told Scruff 30km back over the hills later. He was wearing pants. White floral ones, but at least they were pants. The big rumour of the day was that there was going to be trouble. The other gangs hated the dreaded crazy Nomads with such intensity that they were likely to unite in their enmity and do a little tidying up. There were only 20 or so Nomads, but it might not be a pleasant scene.

We drifted out front so the photographer could daunt some citizens. Bruno Lawrence, sitting under a striped trilby behind his drums on the main stage, was leading his temporary jazz band Jazzmin through a sparky set of straight stuff. In a tent backstage, there was food for sale and a bar set up featuring rare items like very cold beer, spirits and even ice. There was John Dix, another of the festival organisers and author of the definitive New Zealand rock tome Stranded in Paradise. He was muttering about those crazy Nomads. “They won’t talk to me cause I’m a honky.”

Out on the big stage, Corben Simpson, New Zealand’s Michael Stipe of two decades ago, in his cap and handlebar moustache looking like Captain Trip, was whirling for the umpteenth time into his big (and only) hit from his time with BLERTA, 'Dance All Around the World'. Amazing voice, difficult personality. He brought on Sonny Day for a (very) slow blues. They looked like a pair of old lost prophets up there. Certainly, the two of them had been operating the lower end of the rock circuit for years at very low profits.

Back in the backstage bar, Keighley was talking business at the next table. He was managing The Mutton Birds. "Their new single’s lovely... interesting... Student stations will love it” (ie, wasn’t catchy). The weather was interesting too, in a patchy, gusty sort of way. The heat unfortunately drove Scruff back into his frock. I wished I hadn’t asked, in the middle of the bar, what he wore under the thing. He showed us. Arrrgh. Be careful onstage in this wind, I warned my wild photographer. I didn’t like the grin I got back.

The fields were sown with beer cans and that occasional traditional festival sight — a comatose body. The police, who were plentiful but playing it low-key, must have decided it was going to rain. Some of them were sweating through their moustaches in their long coats. Up on the main stage, pop movers of the time Supergroove were doing their bratty, funky, rappy thing. A bit earnest and overheated for that beered-up crowd. They were followed by Wellington city/country heroes The Warratahs, minus a piano for resident tinkler Wayne Mason (who started his public musical life in the 60s with The Fourmyula). The piano had been mislaid on the road somewhere. He substitutes, at a squeeze, with an accordion.

There were more historic faces backstage — Kevin Borich, the hard rock guitarist and former westie long since based in Australia, who slipped into the spotlight nearly 30 years earlier with The La De Da's and outlived them, fronting an on-going series of trios, all called The Kevin Borich Express. He was 44 and looked fit and fine, as did his wife Melissa (who may not even have been born when The La De Da's were playing).

Then Andrew Fagan was onstage screaming at “the big green trees” to shut up, introducing the title song from his new album, Blisters, with a surreal and sordid tale about herpes and playing a terrific 30 minutes of new songs, backed by his tough, business-like guitar band, Swirly World. No one wanted to take Fagan seriously any more, which was a great pity. After a poppy profile and quite a string of hits with The Mockers in the early 80s, the bright, slightly loopy singer got tired of all the schoolgirls and buggered off to Britain where he married exiled TV rock show presenter Karyn Hay and returned three years later waving a new image — somewhere between Sam Hunt and Chris Knox and operating under the name “Fagan”.

There was a single that no one took much notice of, but more lately he’d glued the “Andrew” bit back on, slipped out a terrific new album and unwrapped his new band, who’d been touring to little effect up to that point. I ran into Karyn in the crowd. We'd fallen out and weren’t talking any more. Though, still feeling the effects from visiting Sam, I forgot about our unfriendliness and lurched at her in what I thought was a friendly manner. She leapt back in terror.

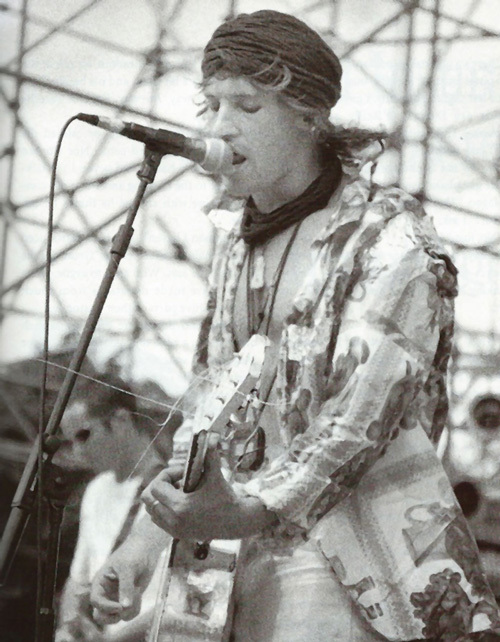

Andrew Fagan - Photo by Scruff

There was a guy in the crowd heading for a fight. He was short and muscular, wearing jeans only, covered in tats and totally wasted, crashing and stumbling into strangers. After a few false starts, someone finally laid into him. I didn’t know what he’d been taking, but he had remarkable powers of recovery, rising again and crashing on through a couple of more serious encounters before eventually the police arrived and hauled him off in handcuffs. Someone I talked to had seen him earlier in the day. “I’m OK now,” he said, “but I’ll be trouble later.” It must be good to know yourself so well.

The news from John Dix was that there’d been a stabbing, a rape and a sexual assault. Dix was in charge of media liaison and he was still getting used to the role. “What’ll I say to the fucking media?” he asked. The old line, I told him. “Pick a town with the same population as this place (around 20,000 now) and ask what its record was for the last 24 hours.”

Dix looked convinced. I'd known him for years and he’d never changed. Well, certainly not his socks. Because of him, I was always on the look-out for a woman called Dot. I already knew of two women called Dot. Dix had been married to both of them, one after the other.

And I had nothing against the second Dot, but I had a strange ambition for Dix to go the whole ellipsis. I was still looking for the third Dot.

Bill Payne, who was also there and who was very tall and who had written a book a couple of years earlier on the New Zealand gang scene, nearly got himself taken to pieces by the Nomads’ women. Something in the book had upset them. “They’re crazies, those Nomads,” someone said. Everyone nodded.

Ian Watkin was onstage introducing Bryant and his band, The Skills, with a legalise-marijuana rave, which got a big roar from a crowd full of stoned eyes. The band made the most of its 30 minutes with a very sparky set, despite a wind so strong it nearly lifted the considerable Bryant off his feet.

Old mate, former big-shot rock promoter, recording studio owner and Herbs manager Hugh Lynn turned up boasting a big smile and a bit of a puku — a change from the wild, speedy old days. He had a new life and a new love and he was extolling the pleasures of clean living, as only an ex-drug fiend could. He used to be serious fun, the only man I knew who used to yell at Customs if they neglected to search him at the airport.

Corben Simpson was getting a bit wild-eyed in the backstage bar, which was hardly anything new. The last time I’d seen Corben was in the Occidental Tavern in Vulcan Lane. He came in jangling one day. He’d been working the poker machines of the inner city and he was carrying kilos of coins in his distended pockets. He came up and turned his crazy eyes on me and started screaming, “Why don’t you interview me? Why don’t you interview me! Make me famous again.”

Hugh’s new love looked nervous. She was new to this sort of company. "Don’t worry," I told her. “Think of it as a wax museum. Tonight they melt.” Scruff was off photographing the gangs. “You stay here,” he told me. That wasn't a problem.

It turned out the festival promoters, worried about the mad, mad Nomads, got Hugh (who had solid gang connections) on the phone to Black Power’s Dennis O’Reilly, a man of standing in gangland. He was being driven over from Napier with some “associates” to conciliate.

The Borich Express were on stage under a hot sun and a wild wind, mixing up a potent brew of Hendrix-meets-Angels.

They were expected in an hour or two. The Borich Express were on stage under a hot sun and wild wind, mixing up a potent brew of Hendrix-meets-Angels. They were a bit short on memorable songs, but they played like a well-oiled engine. The crowd approved, though it was a hardcore kind of crowd.

Scruff was onstage taking pictures and I was busy hoping the wind didn’t blow his dress over his shaved head. I didn’t think the crowd was hardcore enough for that.

The bill of fare on this main music day was a bit of a weird one — a sometimes-strange compromise between old and new wave. That night, for instance, hard-hitting left-fielders Straitjacket Fits were the unlikely filling in a sandwich between Shona Laing and a reformed-for-the-occasion Hello Sailor. Following on from the Borich boogie was Bill Direen, a crusty outsider whose music was sometimes —often times — wildly esoteric. And so was Direen himself, who proved to be a real wild Bill when his sound was cut off after he overran his 30-minute time slot. Direen totally lost his cool and ended up in an onstage brawl with the roadies.

The crowd roared its approval. That sort of thing usually only happened in front of the stage, not in front of the audience. It was looking like a crew-kill-star scenario but, to the disappointment of the crowd, it stopped short of homicide. Direen appeared backstage afterwards sporting a bloody bandage on his hooter, a few new scars and a very tense look.

Then Sam Hunt was on, with an edge-of-the-stage rave-with-poems that totally connected with the audience, followed by the lovely westie queen Jan Hellriegel and band with a very stylish set. The nice thing about the festival was that all the acts came in bite-sized, 30-minute chunks, only 15 minutes apart. The exceptions were the expatriates, Borich and Dragon, who had all of 45 minutes to prove their points.

Dave Dobbyn, Shona Laing and ex-Ray Columbus and The Invaders bassist Billy Kristian had arrived backstage, Scruff was suddenly wearing a (vaguely) matching blouse and I was feeling fried. Too much sun, too much of the sponsor’s product. I couldn’t tell whether that pill someone gave me earlier was working at all. But at least I was still upright.

The problem with festivals always used to be the self-balancing act. The first day, you were naturally excited about being there and meeting old friends and so you tended to take too much of everything and get a bit messy. But then, so did everyone else, so it made sense.

The second day, suffering pain and remorse, you'd under-do it and it was never as much fun. And by the third day, you'd think, what the hell, and go three steps beyond the first day. Which was why you woke on the fourth day surprised to find yourself alive and swearing to never darken another crowded field again.

It was an awesome sight as empty beer cans darkened the sky, raining in from everywhere on a single segment of the crowd.

In the midst of Dobbyn’s wham-bam performance, another festival tradition erupted – a can fight. It was an awesome sight as empty beer cans darkened the sky, raining in from everywhere on a single segment of the crowd that must have done something to seriously piss off everyone else. The fight was spreading. A can whizzed past the end of my nose. I retreated.

There was a guy collapsed, face down, under the pines next to Scruff’s bus. He’d been there since the previous night, apparently. I assumed he was alive. Inside the bus were Dennis O’Reilly and three sidekicks. They chatted, I listened, we smoked. I didn’t take notes. Out by the backstage gate, I ran into a police gang liaison officer who said his name was Magoo. “That’s what they call me,” he said.

“Mr?” I asked. “No, just Magoo.”

He said the gangs were out there with their patches off. What about the crazy, blood-drinking Nomads, I asked him. “It's tense,” he said. Later I was told that it wasn’t only honkies the Nomads wouldn't talk to. The head Nomad was a convicted killer and he'd only negotiate with other convicted killers. So convicted killers were brought in and, one at a time, each visited the head of the dreaded Nomads with a bottle of Scotch. It took three visits to lay him low.

Shona Laing was onstage, the day was darkening into dusk and it was raining. There were old Sailors about — Harry Lyon, Graham Brazier and Dave McArtney. They’d been teasing their way towards getting back together again for a while. The last time they did it, in the 80s, they all but sank their ship with a shaky album full of synthesisers and airbrushed photos. There was quite a bit of cred hanging on the Mountain Rock performance — all the more so because so many of their peers were present. They looked as nonchalant as ever, though.

The rain was still about when Straitjacket Fits hit the stage to deliver a fearsome performance that must have put a quiver into all those black jeans out there. The rain was the act putting on the fearsome performance when Hello Sailor hit the lights. But they pulled it off. Playing into sheets of wet stuff, with the laser lights transforming it into purple rain, they played like heroes. Drenched heroes. Dragon, on the other hand, mostly painted by numbers – and in the old colours. Marc Hunter, trussed up in a biker jacket with his shirt hanging out, though, was less snarky with the stage patter than he used to be.

Backstage, it was getting crazy in the bar tent, which was jammed with old faces off their faces. Bruno Lawrence tried to land a head-butt on me at the bar (he still remembered a bad review I’d given an old band of his), but he was a bit short and his baseball cap got in the way.

Anyway, I wasn’t sure he meant it. Age had not diminished nor calmed the wild drummer-turned-actor. Nor Corben Simpson, who had moved beyond the talking stage to the howling and weird eye-contact routine with anyone he thought he could scare. A woman I hadn’t even been introduced to ripped a hair out of my chest shouting, “Great, got the follicle.” Who was I to argue, when others had made donations from much more sensitive parts of their anatomies? Bryant and Borich were grinning at each other across a table top, a couple of massive Magogs were watching the madness impassively from the side, and Scruff was encouraging potential subjects to excessive behaviour. They didn't need much encouraging.

Ah, rock festivals. Nothing had changed backstage except the ages of the participants.

Ah, rock festivals. Nothing had changed backstage except the ages of the participants. Out front, not even the ages had changed.

Some of the gypsies were sprouting grey hair, but that might have been brought on by the White Lightning. The toilets got pretty visceral and the beer just about ran out a couple of times — causing more fear among the festival organisers than even the dreaded Nomads did — but despite all the booze, the dope, the gangs, the black jeans, the wind, the sun, the rain and the occasional farm animal (I recall tripping over a goose), farms weren’t pillaged, policemen set alight or the hills left littered with corpses.

By 3am on Sunday I wasn't sure I was going to get out alive, but that was hardly a new feeling. And I did — as did 25,000 or so other people (including even the Nomads).

It was, as these things often were, a success — musically, financially and, on some levels anyway, socially. The other thing that hadn’t changed was that the mainstream media took their usual line, accentuating the negative (which, considering the size and state of the crowd, was a lot less than it might have been). A bit like covering a National Party conference and only reporting that the leader had a nosebleed.

Scruff was probably still down there in his green bus on a lonely knoll and I don’t know if that bloke under the pines ever got up.

But the Woodstock/Woodville jokes weren’t appropriate. The hippies were thin on the ground and there was a hell of a lot more denim than there was muslin. Everything’s as it should be. That wasn’t the summer of love.

–

This story first appeared in The Awful Truth - An unauthorised biography by Colin Hogg in 1996. © 1996 Colin Hogg, used by permission.