AudioCulture

The noisy library of New Zealand music

Te pātaka korihi o ngā puoro o Aotearoa

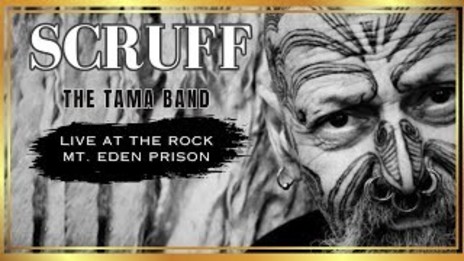

Scruff

aka Peter Ralph

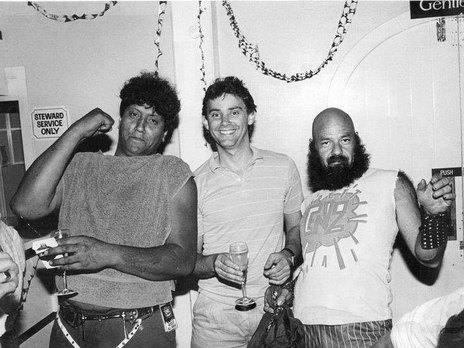

As a personal minder he mixed with an array of international stars, including David Bowie, Bob Dylan and Tina Turner. Debbie Harry flashed her breasts at him, Dave Stewart of the Eurythmics gave him a five-figure bonus, U2, UB40 and The Stranglers offered him off-shore employment. And Dr Feelgood's Lee Brilleaux wanted to remain in New Zealand, just to hang out with him.

In 1993 I fronted up to Auckland's Liquor Licensing Authority on Scruff's behalf. The police had objected to the renewal of his general manager's certificate. He was well-known throughout the NZ music industry and had a folder of references from personal friends like promoter Hugh Lynn and Auckland deputy mayor Phil Warren, a former promoter himself; references from promoters, nightclub owners, security companies, record company heads, production and stage managers.

His nefarious past had gone unnoticed when he had applied for his general manager's certificate in the mid-1980s, allowing him to operate or manage licensed premises. Rarely able to finance his own business, others put up the bucks and used Scruff's name. Scruff's Bar at the bottom of Queen Street didn't last long and in 1987 he briefly took over the Foundry/Brat premises in Nelson Street, before managing the bottom bar at the Station Hotel for Don “The Whale” Hooper, which gained a notorious reputation for its strippers and outrageous activities spearheaded by the host himself: dancing naked on the pool table, pumping and grinding, doing the go-go, Michael Jackson moves and James Brown yelps, uninhibited. On one occasion, in full view, he copulated with one of the strippers.

I was aware of Scruff's former life but, laid before me, it was difficult to reconcile it with the man I knew.

There was other entertainment – Herbs and Jay Clarkson's Breathing Cage performed at The Station, and Emma Paki's first paid performance was there. But mostly it was Scruff's muso mates, and his loyalty didn't necessarily make for good business decisions while his personal musical tastes could be at odds with everyone else.

His last club, 1992-93, in the heart of seedy Fort Street, was named Scruff's Ultimate Rock Fantasy Megadrome, a hang-out for gangs of all persuasions (minus their patches, his only rule) which led to the police querying how this guy had slipped under the radar.

At the liquor licensing authority hearing, Scruff's lawyer greeted me like I was Mother Theresa, pumping my hand and thanking me profusely. "Are you familiar with Peter's criminal record?" he asked, handing me a sheath of papers itemising a trail of bad behaviour – armed robbery, assault, burglary, theft, possession of heroin, selling drugs to an undercover policeman.

I was aware of Scruff's former life but, laid before me, it was difficult to reconcile it with the man I knew. By the time I met Scruff, he was already a fully-formed freak.

Peter Lindsay Ralph was born 4 June 1949 in Huntly but raised in Auckland – Sandringham, Mt Eden, Pt Chevalier, Grey Lynn. The youngest of three, he came from a respectable hard-working family, although his brother Alan's rebellious streak saw him hang with the King Cobras gang. Peter inherited his nickname from Alan, and for many years they were Big Scruff and Little Scruff. Like Peter, Alan would later change his life around, becoming an artist and carver of note; he died in 1998.

Leaving school in 1964, Peter followed Alan to the Kawerau timber mills, where Little Scruff lost his right-hand fingers in a circular saw, leaving him with stubby digits, a lack of self confidence and a sense of insecurity. His family believed that the accident led to his subsequent criminal activities, and his persistent anti-social behaviour led to incarceration at Oakley Hospital, receiving ECT treatment. He remained bitter about his Oakley experiences and he was left with occasional blinding headaches for the rest of his life.

In 1968, on the eve of a North Island tour, The La De Da’s invited Scruff to be their minder.

Throughout the late 1960s, frequenting the Auckland nightclubs, he earned a reputation as a ferocious street fighter. Not particularly big (5' 9" and generally weighing around the 90kg mark), he made up for it with unbridled aggression. Some called it fearless; looking back, Scruff himself said he was a "psychopath". He just didn't care, blood, pain and disorientation was no detererrent.

In 1968, on the eve of a North Island tour, The La De Da’s invited Scruff to be their minder. He told me many years later, "In Auckland the band was alright, they had heaps of mates around, but out of town they had trouble with jealous boyfriends, which is where I came in." Other Auckland groups began taking Scruff with them for provincial performances, leading to employment as a nightclub bouncer. "Hit 'em first and ask questions later," was how he described those early days.

He left prison for the last time in 1981. There were a string of security jobs, from Rainton Hastie's strip joints to music nightclubs. Eden Security found a role for him. Hugh Lynn: "We didn't use Scruff in uniform. He was someone that would spend more time travelling back and forward to the gig, in the van, more of a bodyguard/personal assistant, a person who dealt with more than just security, who understood the nature of the business and could make the right decision on the spot, or phone for directions, more closely aligned to the promoter, and the working of the gig."

There could be other duties for someone “more closely aligned to the promoter”. Tracey Magan, daughter of promoter Ian Magan, remembers watching concerts sidestage with Scruff as her babysitter. Indeed, there was little Scruff wouldn't do. At festival sites, prior to opening, he could be dispatched to secure the main gate during the graveyard shift, sitting in the caravan like a buddha, content with his own company, nothing to do except be there and shoo away teenage sight-seers at 3am.

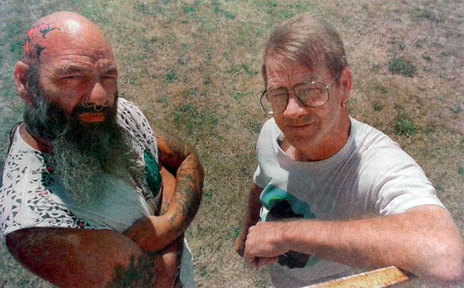

It wasn't all security; he also picked up stagework, teamed with a close-knit group which included Laurie Bell, the Marsden twins Eric and Steve (formerly of punk band The Androidss), Greg Carroll and the gigantic Steve Kahuta, AKA “Foot”. Infamous for after concert/tour parties, they called everything “sick” – “sick” jokes, “sick” behaviour, “sick” stories – and called themselves The Sick Crew. Fuelled by a variety of stimulants, Scruff would tear his clothes off screaming, "I am an alien sex god!" He wasn't an alien sex god; he just looked like an alien sex god.

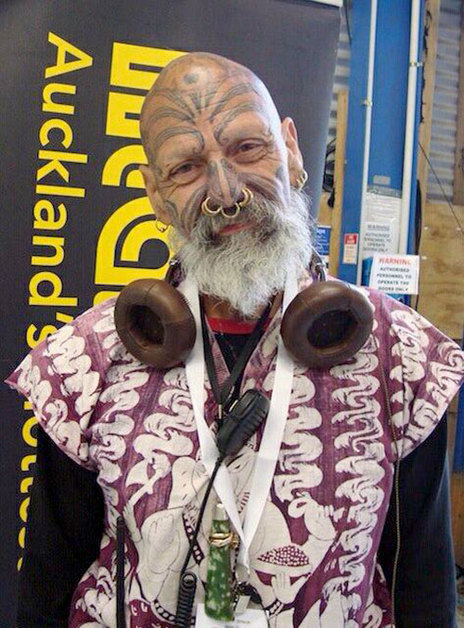

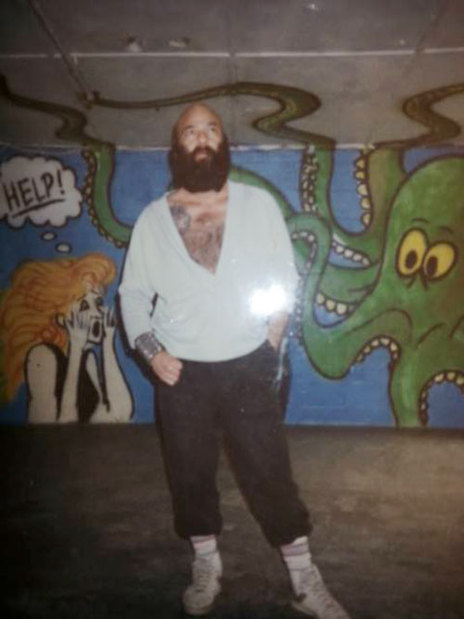

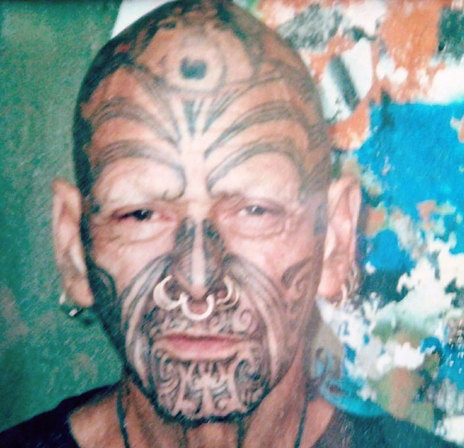

Scruff's appearance had evolved into … something pretty fucking weird. It started in prison, shaving the top of his head and growing a full-length beard; the abundance of body hair and tattoos and the top two missing teeth, knocked out and never replaced, only compounded the gang look. In time, his head would be completely shaved and his head and face fully tattooed. To this, he added gold rings in his ears, nose, lips and eyebrows. At times he sported up to 20 rings, and that was just his head.

The next thing you know Scruff was wearing women's clothes – a “biker-transvestite” look, Colin Hogg labelled it.

To accompany this was The Wardrobe. It began innocuous enough – black T-shirt or tank top, jeans and boots, a typical roadie. To this he added scarves and bandanas, not necessarily placed where intended, and for a spell he nurtured a piratical appearance. But, well, the next thing you know Scruff was wearing women's clothes – a “biker-transvestite” look, Colin Hogg labelled it. Blouses and skirts mostly, a gown or two and that awful spandex outfit. He dropped the cardigans early and the wardrobe didn't run to petticoats and stockings, at least not in public – who knows what the crazy bastard was wearing in private. He'd do runs on the charity stores or, as, he once told me, "I'm so poor, I wear my daughter's hand-me-downs." It was just mighty strange and not what you'd call crossdressing, not to that face.

One summer he took to wearing nothing but a loin cloth and became scary hairy man with tattoos in nappies. Cloaks, ponchos and sarongs came and went. He walked from Auckland to Wellington on the Hīkoi For Poverty dressed in eastern robes and sandals which, with the accompanying shepherd's crook, gave him a biblical appearance. He liked that.

It hadn't been all crime and rock and roll. There were relationships, five children in all. Nor was he a permanent party animal. By choice, he went months without drink and drugs and somewhere along the line he became a vegetarian and stuck with it. Indeed, his interests became increasingly hippie-ish. He collected “stuff” – crystals, sea shells, pounamu and bird feathers, all sorts.

And there were pets. For a decade Scruff's most faithful friend was Brindle, an ever-farting English bull terrier. He replaced Brindle with a kunekune, run over while Scruff was living on the open road, and then a much-detested ferret, which disappeared under mysterious circumstances, Scruff always suspecting that one of us had disposed of the rodent.

He drove a variety of vehicles, from hot souped-up cars in the 1980s to house trucks and buses in the 1990s to, briefly, a rickshaw in the 2000s. More often than not, his transport also served as accommodation. He once lived in a covered trailer given to him by the Topp Twins, towed by a tractor.

He lived hand-to-mouth but there were occasional windfalls, which he'd squander on a hired limo, cruising around Auckland with half a dozen mates, maybe a trip out to Helensville, a carton of chilled champagne, a $500 bottle of cognac and a bag or two of other stuff. He'd be broke the following week. In the late 1990s his parents had a Lotto win and flicked him enough to purchase a pretty flash bus, flasher than any transport from his recent past, most of which ran on faith alone. But it was a bugger to maintain so he downgraded and bought himself a fifteen grand camera and that rickshaw.

He excelled at stage security, keeping an eye on the mosh pit with a water pistol, spraying the over enthusiastic or those considering a stage dive.

Along the way, Scruff became a good luck charm for promoters and production managers. He excelled at stage security, keeping an eye on the mosh pit with a water pistol, spraying the over-enthusiastic or those considering a stage dive. A squirt and a shake of the head was all it took.

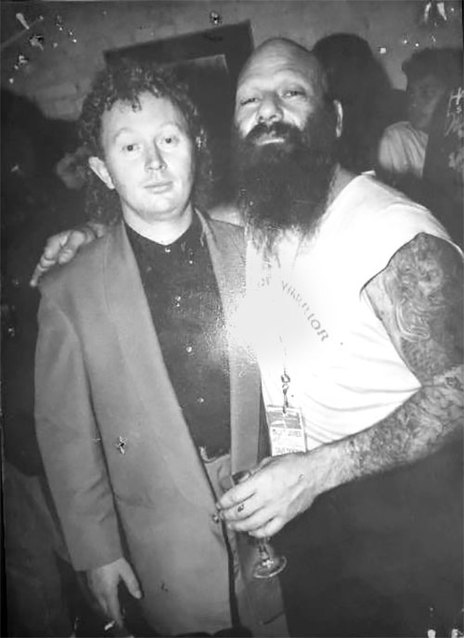

When he accompanied Debbie Harry to the bungee jump on Halsey Street, Auckland, just prior to jumping she screamed "Scruff!" and ripped off her T-shirt, one of Scruff's fondest memories. In 1993 I met Bono for the one and only time, with Scruff, backstage at Western Springs. Greeted warmly, Scruff surprised me when he immediately berated Bono for remarks he'd made from the stage about non-paying punters on the stadium perimeter. "Not everyone is loaded like you, Bono!" Bono took it on the chin.

On another occasion, Scruff acted as personal minder to an international superstar but left mid-tour. "He was bloody rude," he told me later, "rude to everyone around him, including his fans. I told him to get fucked and flew back to Auckland."

There was nothing Scruff wouldn't do and little you couldn't trust him with. I once sent him to the bank on closing time, with ticket money, a substantial amount. As Scruff told it, it was deathly silent when he entered, all eyes on him. Dumping the contents of a bulging canvas bag before the terrified teller, he said, "Don't worry, I'm here to give you money."

After successfully renewing his general manager’s certificate, it was put to use at the Mountain Rock festival, managing the backstage bar. He arrived in Woodville in January 1994 and stayed three years, working at the Masonic Hotel between festivals; when publicans Ross & Felicity Walker shifted to Waihi's Golden Cross Hotel, Scruff went with them.

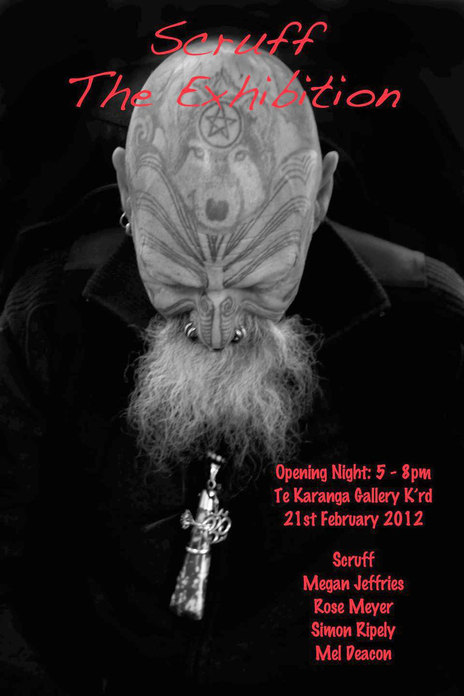

In Waihi, always seeking an artistic outlet, he took to working with pelts; an exhibition followed. Later, there were exhibitions of Scruff's photography, another passion. Three or four summers were spent on the road with the gypsy caravan convoy, selling his pelts and pix, acting as camp security should any trouble arise.

He was offered fulltime positions with several international acts but his criminal record prevented him shifting overseas.

Throughout the 1990s Scruff grew increasingly dispondent about his former life. He was offered fulltime positions with several international acts but his criminal record prevented him shifting overseas. "I can't even go to Australia!" he would exclaim indignantly.

Meanwhile, The Sick Crew had fallen apart. In 1984 there was a sense of pride when one of their number, Greg Carroll, was plucked by U2's Bono as his personal stage assistant. Two years later Greg was killed in a motorcycle accident, just months after Laurie Bell's death in a motor accident while tour managing The Commodores. (Several other Sick Crew members were to die prematurely in the 2000s, including Foot and the Marsden brothers.)

As if to offset his previous life, Scruff was fastidious with payments, road charges and hire purchase agreements mostly. He had a high credit rating. During downtimes there was always social security – no dole for Scruff, his mangled hand gave him a lifetime invalid's benefit. Besides, who outside the entertainment industries would employ him? Who could understand him, his eccentricities, his very appearance?

In the 2000s he picked up work as a film extra in Xena and Hercules (prosthetics not required) and appeared on the music video for Minuit's ‘Fuji’. He had his occasional exhibitions, planned to record his own song and video (‘The Roady Song’), toured several times with 8 Foot Sativa, one of his favourite bands, served as kaitiaki of Area 51, Andrew Featherstone's West Auckland recording studio, and he was Blink's 2IC at Camp A Low Hum events. He immediately appreciated the kaupapa behind the Parihaka International Peace Festival and became a regular presence. He twice contested the Auckland mayoralty, running because "I need a job".

Over recent years, in his sixties, Scruff's employment options were fewer, too old to be lumping PAs or to be effective as hands-on security, he served more as a backstage mascot. Younger crew wouldn't allow him to lift anything heavy and he would potter around rolling up leads; promoters and production managers employed him just to have him around.

He was equally comfortable in the company of household names as he was with the crims from his past and the street people.

In 2013, advised that he had terminal cancer, Scruff accepted it in his customary stoic and matter-of-fact manner. "But no funeral service," he insisted, "and definitely no wake – I don't want my mates having a party if I can't be there!" He died peacefully on 9 August 2014. A memorial gathering later in the week attracted a who's who of the NZ music industry. Paying tribute, longtime friend Dave Dobbyn said, "We can all be thankful to have had such a unique presence in our lives."

Scruff was a loyal friend, loyal and reliable, who never forgot a good turn, repaying 10 times over. He could also be a grumpy bugger; subject to mood swings, he could get awfully depressed. He was equally comfortable in the company of household names as he was with the crims from his past and the street people, those that worked the midnight streets, who frequented the late-closers and early-openers, those spat out by the mental health system and those who chose to live outside society, the panhandlers who slept in parks and under motorway bridges.

Peter Ralph was his own man, unique, as Dave Dobbyn said. The naked freak dancing on the pool table had the same reckless disregard as the younger man brawling in the alley – he just didn't care. Scruff's journey was all there in that face, in those brown eyes that didn't miss much, in the tattoos and in the scars and gnarled features beneath – the violence and crime, the joys and disappointments, electric shocks and headaches, the mischief and fun, the sadness for the street people and the pride in their strength.

Scruff was my mate, always helpful, generally entertaining, sometimes infuriating, but always one of a kind. Hei maumaharatanga ki te tino hoa …

Visit our sister site

NZ On ScreenMade with funding from

NZ On Air