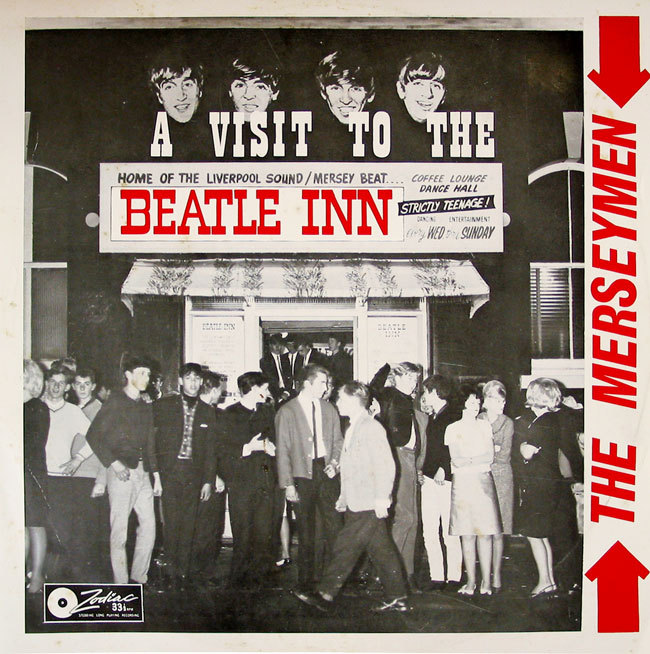

The Merseymen, featuring a young Dylan Taite (as Jett Rink) on drums, with their 1964 album A Visit To The Beatle Inn

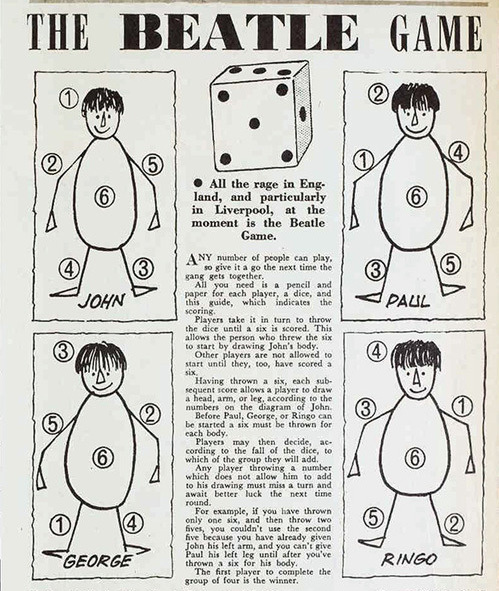

To dislike The Beatles isn’t an opinion, Paul Du Noyer once wrote: it’s a stance. The arrival of The Beatles’ music in New Zealand required a response, whether you were for or against. Young musicians reacted quickly; if you didn’t comb your hair forward, suddenly you looked dated. Bands billed as an adjunct to solo vocalists now looked like clones of Cliff Richard and the Shadows, as old hat as last week’s dance; having a showpony out front implied you were a band but not a group (Ray Columbus and Max Merritt were too strong as personalities for this to be an issue, as were their bands.)

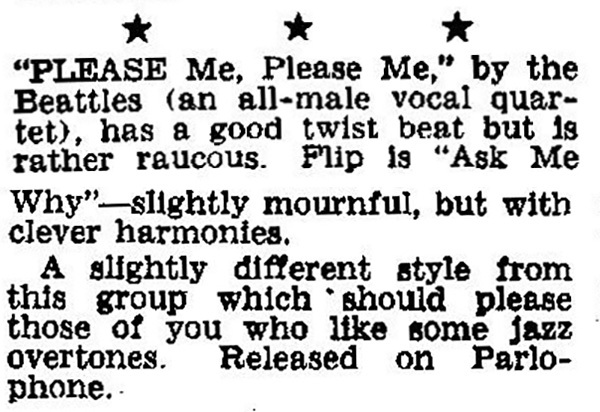

The first mention of The Beatles in New Zealand, in NZ Truth, 2 April, 1963

The immediate impact of The Beatles was acknowledged by Wellington jazz saxophonist, dance-band leader and songwriter Ken Avery in his 1983 memoir Where are the Camels? “These four boys from Liverpool changed the musical face of the world in 12 months flat,” he wrote. “The music business has never been the same since they came on the scene. Amateurs and professionals alike copied them, Arthur Fiedler and his Boston Pops Orchestra played symphonic arrangements of their songs.”

They quickly influenced changes to the live scene and their impact on New Zealand recording would be felt for decades.

But, like many in the old guard, Avery was a little skeptical of the Beatles phenomenon: “Hit followed hit, but as an amateur songwriter I was amazed at the variety of songs that bore the names Lennon and McCartney,” he recalled. “I mentioned this to a well-known music shop manager who told me that, according to his information, the Beatles also had a stable of songwriters working for them. The Beatles bought suitable songs outright for £1000 or so. Now this is all conjecture, but it seems to me that to write a song like ‘Michelle’, one of their big hits, you would have to be born and bred a Frenchman. I don’t think even the most likely lad from Liverpool could come up with the melody and chord structure of ‘Michelle’.”

This attitude may seem laughable now, though in its own way it also pays tribute to The Beatles’ talent: at the time, what they achieved seemed incredible. Less generous towards the group – though still exploiting the “fad” – was Howard Morrison. In 2006 Gerry Merito – the linchpin of the Howard Morrison Quartet – told me of their conflicting reactions to the emergence of The Beatles: “I was really rapt in their music right from the start because it was getting back to a lot of unison singing, and breaking it up with harmony. For ages I’d tried to make the boys sing with lots of our songs in unison. [The Beatles] did the harmony – and then go back to unison. Mix it up instead of harmony, harmony, harmony. After a while it gets boring even though it is pretty. I reckon those guys put a sound out that we should have copied. But Howard wouldn’t go down that track at all. He wasn’t keen.”

HMV Records Beatles catalogue at the time of their June visit. The Beatles would provide the company with a very large part of their turnover into the 1970s.

Prior to The Beatles’ New Zealand tour in June 1964, Morrison recorded the childish ‘I Wanna Cut Your Hair’ with a backing group called the Huhus. He also refused to meet them when they got here. Ringo was asked at the Wellington press conference if he’d heard the song. He said, No – but if it quoted more than two bars, then The Beatles could sue. (Rod Derritt is credited with the parody’s lyrics, but the song is still attributed to Lennon and McCartney.)

We forget how important the hair was. To the clean cut but occasionally bawdy Morrison – and many others – the only men with long hair were either sailors or nancy boys. In a documentary marking the 30th anniversary of The Beatles’ visit, Morrison gave the impression that he thought his Quartet had more talent; seeing the tsunami on the horizon perhaps helped him decide to disband his group later in 1964.

It would be difficult to overstate the impact of The Beatles on New Zealand pop music. They quickly influenced changes to the live scene and their impact on New Zealand recording would be felt for decades.

New Zealand’s live music scene was very healthy before The Beatles were ever heard of. Popular dances regularly took place at venues such as the Hibernian and Spencer Street in Christchurch, the Platterack in Wellington and the Shiralee and Top Twenty in Auckland. These are just a few names in a galaxy of dance halls in the cities and provinces.

In his prologue to When Rock Got Rolling – a history of the early Wellington rock scene – Roger Watkins describes being a drummer in his first band, The Saints. “That was around 1964, and we were heavily into the British explosion – The Searchers, Brian Poole and the Tremeloes, The Shadows (and The Ventures) and so on. I remember being terribly anti the vocal bands – especially The Beatles – because it meant that we had to sing instead of copy the instrumental hits of The Shadows (and The Ventures), and none of us were what could be called singers. Then we noticed that a little problem like that didn’t stop other bands and we jumped on the bandwagon too. We were awful.”

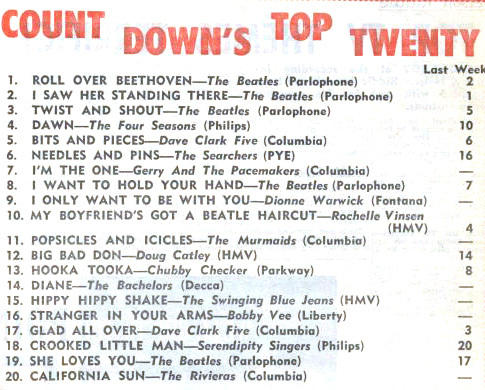

The NZ chart, 29 April, 1964

Two months before The Beatles visited, impresario Phil Warren – astutely anticipating the market – added another club to his empire. The Beatle Inn was situated on Auckland’s Little Queen Street (now underneath the Downtown Centre). It was R18 – anyone over 18 wasn’t allowed in – and the resident band was called The Merseymen. Members of the group included the pioneering rock’n’roll guitarist Bob Paris and a drummer called Jet Rink (AKA Dylan Taite). Crucially, along with Taite, two other members were English: singer Mike Leyton and rhythm guitarist Dave Moan.

Phil Warren's Beatle Inn, down the bottom of Queen Street where the current Downtown Centre sits

“I could see what was going on, and my immediate involvement was to cash in on the craze,” Warren said in 1984. “It held about 300 people, and we opened it Wednesday through Sunday nights and also at lunchtime … we got it away very quickly. It was done out in murals and blow-up pictures of the Beatles. It was an enormously successful room.” The Merseymen’s recordings suggest that they mostly played rock and roll classics. On their 1964 album A Visit to Beatle Inn, ‘I’ll Get You’ is the only Beatles song they recorded.

Meet The Secrets at The Beatle Inn. The Secrets were a Christchurch band, featuring the late Gary Thain who was later in UK band Uriah Heep.

The route taken by Wellington’s Librettos was typical. Founded in 1960, they began playing Shadows instrumentals, and evolved into a beat group with an English-sounding vocalist, harmonies, and their hair combed forward. (To appear on the early TV pop show Let’s Go, the producer insisted they comb it back into quiffs.) Auckland guitarist Roger Skinner – later of the Motivation – began his career in 1957 with a skiffle band, the Kool Kats. By early 1964, he too had formed a group inspired by The Beatles – The Pleasers – and replaced The Librettos on Let’s Go (after combing their hair back).

In Wellington, the changes to the local music scene were exemplified by a shift in the music policy at the notorious Sorrento club on Ghuznee Street. After years as a bohemian jazz Mecca featuring acts such as the Nick Smith Trio and Ricky May, in September 1964 the management announced the music would now be played by a guitar band called The Measles. Led by guitarist Neil Harrap of The Premiers, The Measles also featured Paul West on rhythm guitar, Puni Solomon on bass and Bruno Lawrence on drums. The idea was a big success; soon teenagers were packing out the Sorrento, seven days a week. Jazz was suddenly history at the club.

Even a well-seasoned operator like Max Merritt could have his approach changed by The Beatles. He credited their early cover versions with reviving his interest in R&B, two years before Jimmie Sloggett blew his mind putting on Otis Redding’s ‘Try a Little Tenderness’. “I’d always loved all that music right from the days in Christchurch when the US servicemen brought their records for the jukebox for the dance, but The Beatles brought it right back to that same period again,” said Merritt. “They started doing Motown songs and a lot of old R&B and Chuck Berry and songs by black artists, which introduced the world to a lot of artists that had never been heard before, so it made it a good area for us guys to get back into.”

Throughout the country, pre-Beatles acts in dance halls playing rock’n’roll hits or Shadows-style instrumentals – complete with clockwork-doll stage movements – had to evolve. Among them were Wellington’s Swampdwellers, who became a top drawcard called The Premiers, and incorporated Beatles songs into their set. In Upper Hutt, a teenage group called The Sine Waves would assiduously study every Beatles disc as it came out, and would evolve into The Fourmyula. “All the early Fourmyula stuff, ‘Come with Me’, ‘Alice is There’, all were influenced by The Beatles,” Wayne Mason told me in 1993. “One of the last things we did ['Lullaby'] was a medley with a lot of parts – very Beatle-y, like Abbey Road.”

Around the country, innumerable teenagers were inspired to trek to their musical instrument store and put a down payment on a locally made Jansen guitar. Bands of three guitars and a drum kit became the model.

The Beatles shifted the emphasis to original songs, and showed the creative possibilities of the recording studio.

Live, the Beatles effect was to downplay the idea of a lead singer in favour of several vocalists capable of harmonies. Since time immemorial, the purpose of bands was to get people onto the dance floor, and keep them there using familiar tunes which had proscribed dance steps. Cover versions were the norm. The Beatles shifted the emphasis to original songs, and showed the creative possibilities of the recording studio. Bands could now stretch themselves beyond the limits of the dance hall, and the three-minute restriction on pop singles, a legacy of the 78rpm disc.

My Boyfriend's Got A Beatle Haircut was a hit for Wellington's Rochelle Vinsen in mid-1964. Note the same dancing "moptop" figure used by her record company, HMV, on their Beatles advert above.

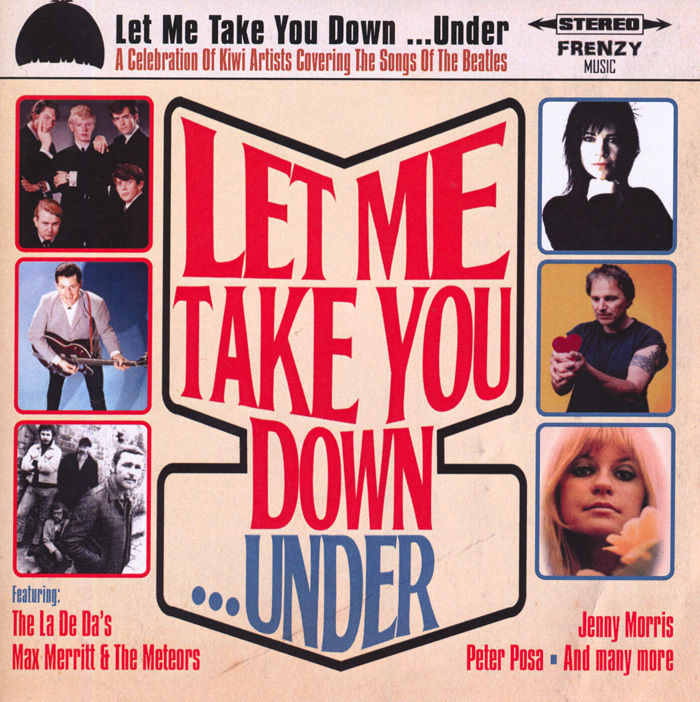

Among recording acts, the earliest responses came from two schools: the opportunists and the copyists. The opportunists are those who rushed out novelty songs that paid tribute to the band when Beatlemania was at its height. Among the most prominent were Dinah Lee with ‘Yeah Yeah We Love Them All’, Rochelle Vinsen with ‘My Boyfriend’s Got A Beatle Haircut’, and Tony and the Initials with ‘Beatle Bridge’. Tommy Adderley had success in Canada with ‘I Just Don’t Understand It’ – released on the Chess label – but to get airplay, he had to change his accent from his native Brummie to Liverpudlian. (Many of the examples mentioned are featured on Grant Gillanders’ fascinating compilation of New Zealand responses to The Beatles, Let Me Take You Down … Under.)

Shane’s Loxene Award-winning single ‘St Paul’ would have to be the peak of this genre, albeit a late entry. Written by US singer and band manager Terry Knight, the song paid tribute to Paul McCartney in 1969, when conspiracy theorists were suggesting he had been dead for a couple of years. Produced by Peter Dawkins and lushly orchestrated by legendary Wellington big-band leader Don Richardson, and packed with musical references to The Beatles, ‘St Paul’ spent six weeks at No.1 in the New Zealand charts, and stayed in the Top 40 for 17 weeks. (Richardson is the most likely source for Ken Avery’s rumour about The Beatles employing outside songwriters.)

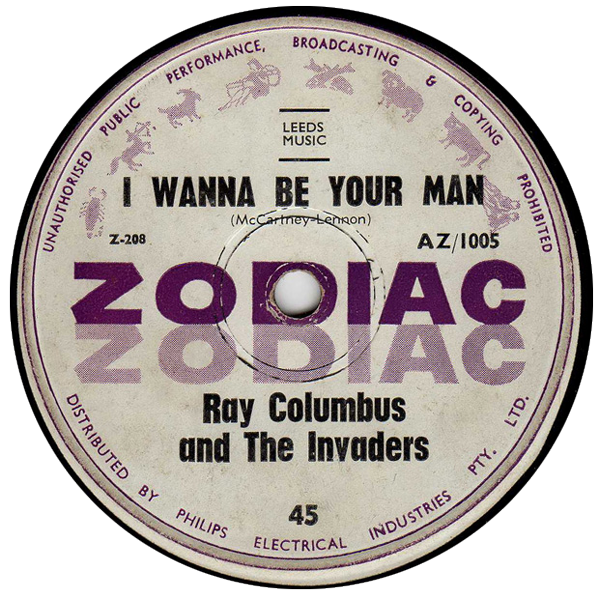

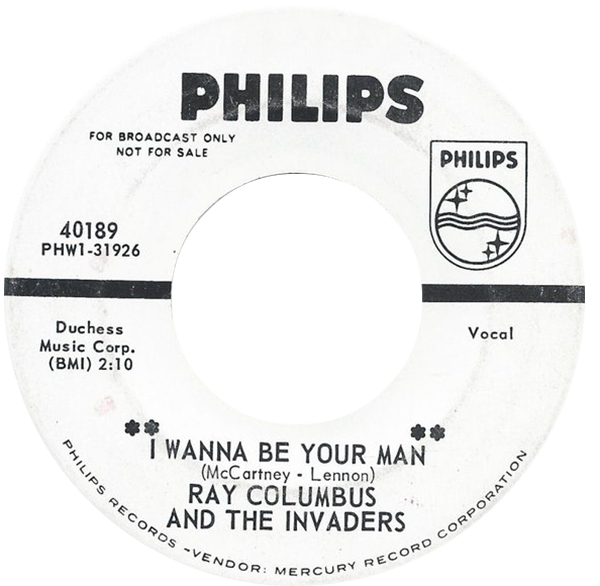

The copyists are those who felt the futile urge to carefully cover a Beatles song either to get radio play, or because their love of the music meant they found the idea irresistible. Perhaps they just wanted the experience, like centuries of fine arts students who copied paintings by the masters. These include Ray Columbus and the Invaders’ ‘I Saw Her Standing There’, The Raydars’ ‘I Feel Fine’ or The La De Da's’ ‘Come Together’.

The Australian release of Ray Columbus and The Invaders' cover of I Wanna Be Your Man

The US promo pressing of Ray Columbus and The Invaders' cover of I Wanna Be Your Man

The next step in maturity was to interpret a Beatles song, to attempt to make it your own. Applicable are Peter Posa’s twanging ‘She’s a Woman’ (pre-dating Jeff Beck by 10 years), Tom Thumb’s horn-driven ‘Hey Bulldog’, Jenny Morris’s countrified ‘I’ve Just Seen a Face’ in 1987, or the Brainchilds’ electronic ‘Tomorrow Never Knows’ in 1994. The Chapta’s ‘With a Little Help From My Friends’ is powerful, but slavish to Joe Cocker’s version, which makes it a copy of an interpretation.

For big statements in this genre, a round of applause goes to 22-year-old Christchurch jazz pianist Barry Markwick, whose late-1964 album Lennon-McCartney Songbook was one of the earliest album-length jazz tributes to The Beatles anywhere. Nine years later came expatriate Dargavillian Mike Perjanik’s Lennon and McCartney: Today and Yesterday. Recorded with his Sydney quartet Synthesis, the album features synth-driven interpretations of mid-period Beatles songs and the best of the early solo years.

The early videos of The Fourmyula, The Avengers and The Underdogs all show the comic influence of Help!

The emulators were those obviously influenced by The Beatles, but with original material. The Fourmyula would be the most prominent early example, also successful were their contemporaries The Avengers and, in the early 1980s, The Mockers. All acquired psychedelic wardrobes to go with their hook-filled songs. The Fourmyula even attempted a concept album, Green B Holiday – everyone wanted to make their own Sgt Pepper – and covered ‘Day Tripper’ on their 1970 live album, which also featured a Wayne Mason original called 'Let It Be' and a guest appearance from Shane.

After ‘Get Back’, The Fourmyula also pared back their aspirations, with the sparseness of ‘Nature’ and the British R&B of ‘Otaki’. Their final statement – the classic Turn Your Back On the Wind, unreleased until 2010 – has the diversity and pacing of Abbey Road, with hard rock, acoustic folk, a big stadium ballad (the title track). Also recorded in the UK, and released in 1971 as their last single, was the aforementioned multi-part suite, ‘Lullaby’. Perhaps HMV NZ thought it would emullate the success of ‘Uncle Albert’/‘Admiral Halsey’.

The early videos of The Fourmyula, The Avengers and The Underdogs all show the comic influence of Help! And surely the music-hall act Hogsnort Rupert was inspired by the nostalgia Paul McCartney displayed on songs such as ‘Your Mother Should Know’ and ‘Maxwell’s Silver Hammer’.

Finally came the inheritors – acts with an original voice though you could hear the DNA. Among them are Split Enz and Crowded House, Th’ Dudes and Dave Dobbyn, Chris Knox with Toy Love (‘Swimming Pool’, ‘Toy Love Song’) or the Tall Dwarfs, The Crocodiles, The Features, Fetus Productions (the striking Fetalmania EP), The Chills and Sneaky Feelings; more recently, Bressa Creeting Cake, The Phoenix Foundation, The Checks and Lawrence Arabia. To name them all could be a new Trivial Pursuit category – or the subject of a thesis. During the singalongs at Exponents gigs, I can’t help but hear a subconscious reference to the long, crowd-sourced fade-out of ‘Hey Jude’.

The 1969 Dizzy Limit single Golden Slumbers / Carry That Weight, released six weeks after The Beatles' Abbey Road. It reached No.9 on the NZ charts, as voted for by Listener readers, and stayed on the charts for seven weeks. The B-Side was Be My Friend, Be My Lover by Stuart Johnstone of the Dizzy Limit.

There are endless curiosities. Two years after his stance about The Beatles’ haircuts, Howard Morrison starred in the musical Don’t Let It Get You. Directed by John O’Shea in homage to Richard Lester’s madcap style with A Hard Day’s Night, the film’s original music was written by Patrick Flynn. As William Dart has pointed out, when Flynn was writing the title track, the melody of ‘A Hard Day’s Night’ must have been stuck his head.

Dart also mentions chanteuse Linn Lorkin, who described the excitement of an imminent new Fabs release in her original song ‘The Beatles New Album’ (on her 1986 album In the Land of Music, recorded under the name Lyn Williamson). Expatriate jazz pianist Judy Bailey recorded a ‘Beatles Medley’ on her 1977 album Solo. And in 1964, at the height of Beatlemania, the Picasso Trio – Timaru folkies – gave the group the benefit of its experience in ‘A Letter to the Beatles’.

Let Me Take You Down, the June 2014 collection of New Zealand cover versions of The Beatles, compiled by Grant Gillanders for his Frenzy label

There are countless cover versions: many, many attempts at ‘Hey Jude’ and The La De Da’s and Golden Harvest both diving into ‘Come Together’ with enthusiastic reverence. The La De Da’s also tried a concept album, The Happy Prince. Acoustic maestros Red Hot Peppers and the Christchurch bluegrass combo Stoney Lonesome Boys both beat Jenny Morris to ‘I’ve Just Seen a Face’ by over a decade. Max Cryer recorded ‘When I’m 64’ and Bid’s Accordion Band from Christchurch returned ‘Michelle’ to the French bistro where Paul McCartney presumably first heard it. The legacy these acts received from the Beatles is multi-faceted. Hooklines, and lots of them; a willingness to experiment; an awareness of diverse musical genres; openness to arrangement and instrumental colour; brevity. Most of all, a love of pure, perfect pop: where smart meets simple, resulting in something that is clever, accessible and irresistible.

Grant Gillanders’ other recent compilation,What Did You Do In The Beat Era … Daddy!!! shows the vitality of New Zealand’s beat scene before and during Beatlemania. At first it may feel like a collection of Freddie and the Dreamers tribute acts (Freddie was the idiot child of the Mersey Sound), but listen closer and you can follow the evolution from the teen-dance rock and roll of Freddie Keil and the Kavaliers, through the wholesome instrumentals imitating The Shadows and The Searchers, and on to garage rock. As shown by When Rock Got Rolling and Hostage to the Beat – Roger Watkins’s scrapbook histories of the 1960s Wellington and Auckland music scenes – there was plenty of rock and roll and beat music being made in New Zealand before the first Beatles song was ever heard here.

Some New Zealand musicians who were contemporaries of the Beatles wanted to eschew or stay aloof from their influence. Feeling above the teen pop market, they saw as their influences The Rolling Stones and The Pretty Things – who both, let’s remember, attempted a Sgt Pepper – and got into harder R&B and “underground” territory. For example, The Librettos feel a lot more comfortable with their original ‘I’m A Dog’ – which sounds like Iggy and the Stooges – than their sweet Mersey Sound pastiche, ‘Baby It’s Love’. Ray Columbus and The Invaders had it both ways: ‘She’s a Mod’ manages to be pure pop and garage rock simultaneously, with the “yeah yeah yeah” chorus being an irresistible, opportunistic hook.

As Robert Forster has pointed out, “Beatles fatigue” set in from the mid-1970s until the early 1990s. Then a renewed wave of respectability for The Beatles occurred, thanks to the Anthology TV series and compilations, and the group’s championing by their descendants: Oasis and other Britpop acts.

At the same time, there were wild things in the woolshed that shared the Beatles revival zeitgeist. If Crowded House’s Temple of Low Men had a sense of journey like Abbey Road, Woodface was like a succinct answer to the eclectic "White Album". It was rich in songs, harmonies, hooks, sounds and genres (never mind the hits, just try ‘Whispers and Moans’). Listen to the Finn brothers’ first album, recorded at Auckland’s Revolver (!) studio, and you might think that Magical Mystery Tour was always playing in the foyer as they entered the building. It isn’t so much the hip references – such as the backwards vocals on ‘Suffer Never’, which could be sampled from ‘Blue Jay Way’ – as the experimental, casual approach.

The Finns’ use of period instruments (the Mellotron, the Chamberlain) and techniques (flanging, double tracking, tape loops and reversals) is the confluence of childhood influences and what they learnt from US producer and Beatles fan Mitchell Froom and his engineering partner Tchad Blake. On Finn this was done with a knowing wink; it’s not serious. But on Dave Dobbyn’s Twist – also recorded at Revolver in late 1994, and produced by Neil Finn, with Blake again at the desk – this emulation is stepped up a level. The album’s powerful opener ‘Lap of the Gods’ shows what happens when a more imaginative mind than Noel Gallagher’s studies Revolver and decides to use the same palette of effects, instruments and harmonies. And if ‘It Dawned On Me’ is Dobbyn’s ‘Yesterday’, ‘Into Temptation’ is Neil Finn’s.

Finn and Twist are 20 years old now. The albums came nearly 15 years after Split Enz entered the 1980s with True Colours, when the group’s return to Beatles values – brevity, catchiness – finally secured them a wide audience. The album opens with snippets of voices, like ‘Taxman’, then there is a triple-punch of perfect, post-punk pop: ‘Shark Attack’, ‘I Got You’ and ‘What’s the Matter With You’.

After the mealy mouthed 70s, when rock became art, these songs exemplified the Beatles influence. ‘Shark Attack’ and ‘What’s the Matter With You’ both capture what David Hepworth has described as the Beatles technique of writing songs that “started in the middle and finished soon afterwards”. Similarly, Ian Morris had ‘A Hard Day’s Night’ in mind when producing DD Smash’s ‘The Devil You Know’: it opens at full throttle.

“It is stupid comparing us to the Beatles,” Crowded House drummer Paul Hester once said. “There were four of them. There are only three of us.” Neil Finn has described his music being compared to the Beatles as a “burden”, while also being flattering. Finding the references is a fun game for musical train-spotters, but has the effect of diminishing the originality of the work. One of the last recordings by the original Crowded House, though, was a tribute to The Beatles: “Not the Girl You Think You Are’ managed to channel both Lennon and McCartney simultaneously. (Paul McCartney repaid the tribute with the organ solo on 1997’s ‘Young Boy’.) And Liam and Neil Finn’s charming version of ‘Two of Us’, on the I Am Sam soundtrack, shows how the songs of The Beatles infiltrate the playlist at family singalongs.

The impact of The Beatles on musicians has been profound; it was immediate and has lasted generations. In 1967, Christchurch guitarist Jim Hall was at Canterbury University. “It had a very stuffy music department but I remember the buzz of excitement when someone came in, running down from the World Record Shop on Cashel Street with a copy of Sgt Pepper and put it on. It completely dominated the day. It was an historic event.

“I spent most of my time organising a series of concerts – complete reproductions of things off the "White Album" with the university orchestra. To sing them was a teenager called Malcolm McNeill, who was the only available person who had the chops. At the time it was an infamous concert. When it was good it was good and when it was bad it was a heap of shit. But the arrangements were absolutely authentic, lovingly transcribed.”

At Abbey Road in early 1969, The Fourmyula were recording in one studio while The Beatles were working on ‘Oh Darling’ in another. They fought back nerves to say hello. “I tell you what, we just could not concentrate after that, we were shot to pieces,” Wayne Mason recalled in 1993. “The little boys were just shaking in awe.”

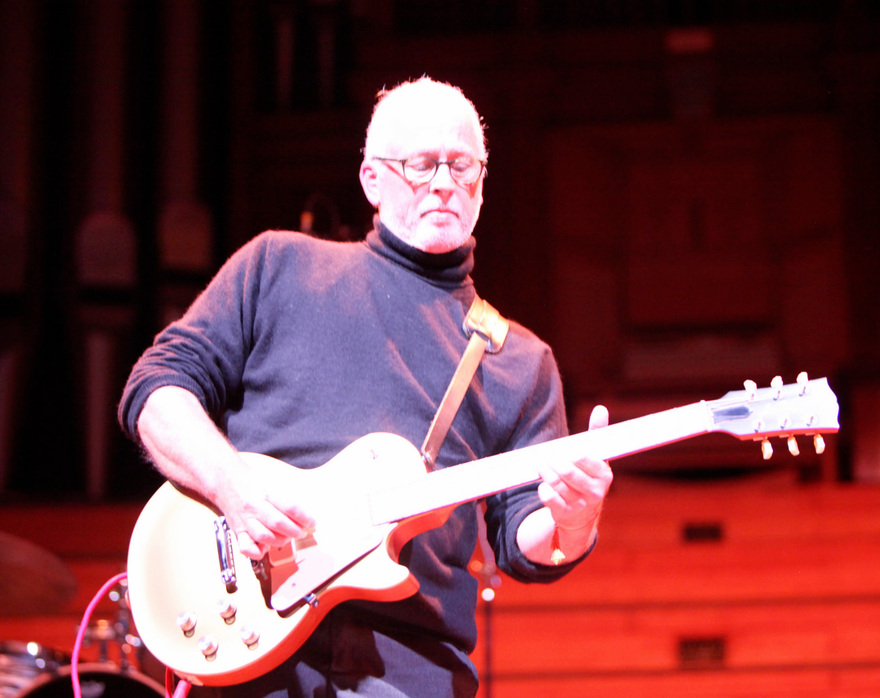

Mike Chunn: "I bought a bass guitar and dreamed the dream. I have imitated McCartney ever since." - Photo by Murray Cammick

In Auckland, the day Abbey Road came out in late 1969, Mike Chunn gathered with his fellow sixth-formers in a Sacred Heart College common room. “The needle was put on track one, side one. We sat around the gramophone and stared at the floor. I was delighted. Side one finished. We turned the disc over and played side two. No one talked during it. After 40 minutes, it was over. We looked up. We beamed. We played it again … In the manner of a disciple, I bought a bass guitar and dreamed the dream. I have imitated McCartney ever since.”

Eight years later, Chunn’s school friends Tim and Neil Finn were introduced to Paul McCartney at Abbey Road, after Geoff Emerick produced Split Enz’s Dizrythmia. “Paul said he’d seen Split Enz on television the night before, so it was propitious timing,” Tim Finn said in 1993. “He said he liked my song ‘Charlie’. That sent a shiver down my spine.”

In Invercargill, after wallowing in the singles, Chris Knox acquired a job lot of Beatles albums in 1966, when a girl down the street had gone off the band. “She became a Monkees freak,” he told me in 1993. Knox would soon become a freak for the psychedelic Beatles. On Saturday nights when his parents went out, he would cook up “a frypan full of chips, turn the lights off, put the TV on, tune into two different radio stations, put them into different corners of the room, put ‘Revolution No 9’ on full bore, lie on my back with my eyes closed and listen to the whole cacophony. So that was the beginnings of my love for over-the-top, crazed noise. I should say, too, that the Tall Dwarfs and my own solo records have repeatedly ripped off The Beatles. All over the place. They crop up left, right and centre.”

Jed Town talks The Beatles with Graham Reid - Q: If you could co-write with anyone, it would be?

A: McCartney

Fifty years after The Beatles’ music was first heard in New Zealand, the influence continues through generations of musicians. In 2013 Matthew Bannister, formerly of Sneaky Feelings, paid them the ultimate tribute with Evolver. As “One Man Bannister” he recorded his own interpretations of the complete Revolver album, approaching each song with a fresh arrangement, rhythm and instrumentation. And in 2014, The Phoenix Foundation – whose parents are of the 1960s generation – most emphatically declared their respect with their exuberant song ‘Bob Lennon John Dylan’ on the Tom’s Lunch EP. The production is more Britpop than Mersey Sound – until the guitar solo, which is put through a Revolver filter.

In June 2014, to mark the half-century since The Beatles stepped on the Auckland Town Hall stage, Mike Chunn re-lived the moment. With a cast of nearly 350 musicians, A Strange Day’s Night was a pair of celebratory thanksgiving concerts paying tribute to The Beatles. Among the performers were Tim Finn, Rikki Morris, Jim Hall, Jordan Luck and promising school bands and choirs. “The Beatles were a huge, powerful influence,” Finn once told me. “That group was pretty much the reason I’m doing what I’m doing today. They affected my life to that extent.” The proceeds went to Play It Strange, the trust set up by Chunn to encourage school children to write songs. The impact of the act we’ve known for all these years will last for a while longer, and satisfaction is guaranteed for all.

Fiona McDonald at A Strange Day’s Night, June 2014 - Photo by Jason Hailes. Courtesy of the Play It Strange Trust.

Split Enz member Eddie Rayner at the June 2014 A Strange Day's Night shows - Photo by Jason Hailes. Courtesy of the Play It Strange Trust.

Geoff Chunn at the June 2014 A Strange Day's Night shows - Photo by Jason Hailes. Courtesy of the Play It Strange Trust.

Mike Chunn and Jim Hall, A Strange Day’s Night, June 2014 - Photo by Jason Hailes. Courtesy of the Play It Strange Trust.