AudioCulture

The noisy library of New Zealand music

Te pātaka korihi o ngā puoro o Aotearoa

Ross France

France grew up in Blenheim, and by the time he reached high school he was, “writing songs and getting little bands together to record them,” with himself on vocals. When he moved to Wellington to study law in 1973, the musical dream took shape.

“I was in a hall of residence and the guy down the hall played guitar. We hit the folk circuit and we had a residency at the Chez Paree in Wellington,” he says. “But then I got a hankering to play in a rock band.”

In 1974, a drummer friend directed his attention to some acquaintances who worked for New Zealand Freighters down on the Wellington waterfront.

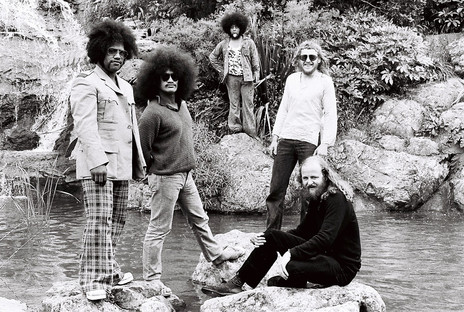

Storm became the resident band at Ali Baba’s in Wellington.

“They were all Māori guys who were on the fringes of Black Power. We formed a band called Storm – and that band changed my life. It was a covers band, Hendrix-influenced, and I was the singer – but they were all really good singers.”

With Mahauriki brothers on lead and rhythm guitars, Danny Makamaka on bass, Dave Alexander on drums and France on lead vocals, Storm became the resident band at Ali Baba’s in Wellington.

“I was a law clerk at the Ministry of Transport, [while] playing Thursday, Friday and Saturday night, 9pm to 3am, three quarters of an hour on and a quarter of an hour off. It was hard work – I didn’t go to work on Friday very often.”

Denis O’Reilly, who had been doing street-level tenant protection work with Black Power, “kept coming to our practices” and soon became Storm’s manager.

“He ended up getting us an Arts Council grant, which we used to buy a bus. We ended up touring the North Island staying on marae. Although I’ve got whakapapa, I’d never been on a marae. So we stayed on marae right up through Hawke’s Bay, Gisborne, Coromandel, Auckland, North Auckland.”

O’Reilly recalled in a 2005 blog post that “in the style of BLERTA we had the obligatory tour bus, a converted railway workers’ vehicle, half seating and half for equipment.”

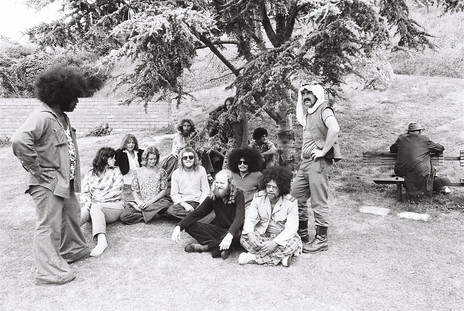

O’Reilly and the band booked all their own venues and Storm had virtually no media coverage, and certainly no radio support, but they managed to get the word out to the extent that they sold out two nights at the Whangarei Town Hall. The tour culminated in a big free show in Albert Park in Auckland. The day before the Albert Park gig, they were photographed on top of their bus outside the People’s Union in Ponsonby – a place where France would have future business.

But after the tour, the excitement dissipated. “We were keen to be professional, but the Black Power connection was a problem, even though our guys weren’t in the gang,” France says. “It was New Zealand Breweries or nothing, really. And if you couldn’t get on that circuit, you couldn’t do it. And we just couldn’t. They wouldn’t give us gigs.”

France also wanted to play original songs and not covers. He moved to Auckland in 1976 and started playing at the Timatanga commune in Whenuapai, with Paul Lee of Cruise Lane and his wife Helen. They played some of France’s songs.

“They weren’t political songs. I was just trying to cut my teeth on writing soul and funk songs. ‘Pretty Up On Your Insides’ was my best one.”

During the Storm tour, France had been put up by Ponsonby activists Fred Ellis and Betty Wark (“we called them the King and Queen of Ponsonby”) and he reconnected with them to establish a labour co-operative modelled on one O’Reilly ran in Wellington. Among other things, they began coordinating government-funded PEP schemes.

“The most success of the schemes was with the Wharewaka brothers out in Glen Innes. They built the wall right round the Panmure Basin and they used that money to buy land out in East Tamaki and built what became the Factory nightclub. We finally got them a liquor licence. They’d been busted a few times, but once we finally made an application, we had quite a good lawyer doing it and we got them the licence.”

Eventually, he says, “with the work trusts and co-ops, everyone got sick of doing shit work – everyone wanted to be artists, not on the end of a shovel.”

The art came via O’Reilly.

“Denis had been to England and the West Indies on some sort of Commonwealth scholarship and he met this group in London called Keskidee, which was an art and theatre complex in London, populated with Africans and West Indians. He hatched this idea to bring Keskidee out to New Zealand and tour them. And we sent Tigi Ness [then a member of the Polynesian Panthers] over there to check them out – and Tigi came back Rasta!”

The collective also introduced France to a young Tongan activist called Will ‘Ilolahia.

Thus was born the Auckland Rastafarian movement. Keskidee’s subsequent tour of New Zealand in 1979 was a turbulent affair subsequently documented in Keskidee Aroha, a film by Merata Mita and Martyn Sanderson.

The collective also introduced France to a young Tongan activist called Will ‘Ilolahia. It would become an important and productive friendship.

“The Socialist Unity party were having a social and they were looking for a band. I spoke to Will and he said, I know this band Herbs, they’re okay. They came and played and I thought they were terrific.

“So we met with them at the Tangaroa College woodwork shop. They were a covers band at the time, and we put together a proposal about writing songs and developing their own repertoire to the band.

“I knew Daniel Keighley and I talked to them about this band and he said, well, if you can get it together I’ll give you a spot at Sweetwaters.”

Even with the promise of a Sweetwaters slot, Herbs’ then bass player wasn’t keen. John Berkley was recruited as a substitute and the work went on.

“Right up until about two weeks before Sweetwaters, we were talking about pulling it because it wasn’t coming together. Well, it was a beautiful sunny day, out the band came, Toni [Fonoti] in a straw hat and a lavalava, and the first song was ‘96 Degrees in the Shade’. And it was amazing, just incredible.

“So the next day we had Australian promoters ringing up wanting to tour the band through Australia.”

It’s no exaggeration to say that Pacific reggae took form that day at Sweetwaters, although France believes its hallmarks were always there.

“If you listen to Fred Faleauto’s drumming, particularly on Light of the Pacific, that syncopated snare that he has, it had its own sound.”

For all the success of the Sweetwaters show, the local music industry was not receptive to Herbs.

“They wanted to play full time but no one would give them gigs. No one played them on the radio. But Will had an association with Hugh Lynn, which meant they were able to get into Mascot studio. And Hugh put an enormous amount of resources into Herbs. In those days Hugh could be a difficult personality, but give him his due – Herbs was hard work.”

With Phil Toms joining on bass, Herbs recorded the extraordinary Whats’ Be Happen? mini-album at Mascot. Toms contributed one song, Fonoti four.

“Bob Marley died – and a day or two later, Toni arrived at the studio with ‘Reggae’s Doing Fine’ and they recorded it straight away, virtually live. It was so powerful.”

France wrote the album’s lead song, the powerful ‘Azania (Soon Come)’, written ahead of the 1981 Springbok rugby tour.

“There was a sense of foreboding,” at the time he wrote the song, he recalls. “It was like there was going to be a civil war if it went ahead. And there was.”

France was among the protesters on the field at the first game in Hamilton and as the tour went on, he would start to hear his fellow protestors psych themselves up with the chant from ‘Azania’.

France’s friendship with Mita had continued and her son, Rafer Rautjoki, was a regular babysitter for France and his then-wife. He and Rautjoki both bought saxophones and started learning to play them at the same time – and then got an offer. Herbs had a return engagement at the following year’s Sweetwaters.

“And they said if you can get it together you can be part of the horn section with Maurie Watene. So six months after we started playing we played on Friday night at Sweetwaters, before INXS, to 40,000 people!”

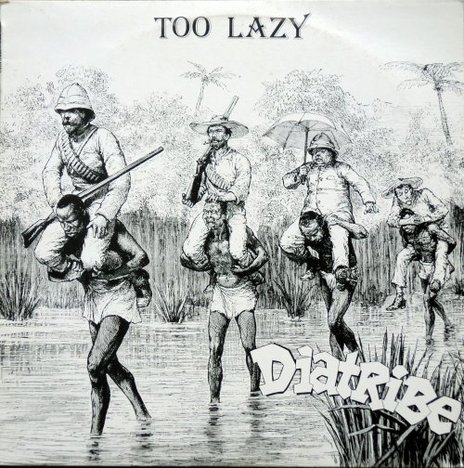

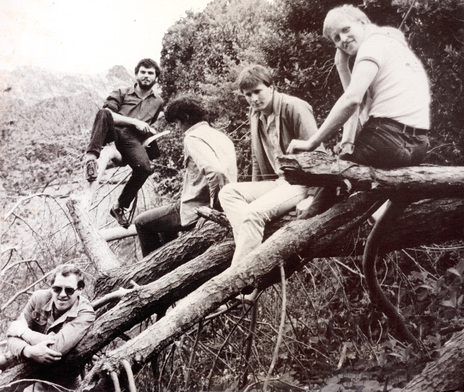

While ‘Ilolahia became Herbs’ full-time manager, in 1983 France and Rautjoki formed their own band, Diatribe, with Berkley on bass, Chris Whyte on drums and Peter Kirkbride on guitar and vocals. Rautjoki, by now a self-taught multi-instrumentalist, would show up variously on bass, drums, keyboards, saxophone and, for the big shows, vibes.

sessions at Mascot producing Diatribe’s only recording, the ‘Too Lazy’ EP on Warrior.

“With Herbs you couldn’t be sure what time everyone would turn up, but this band had a work ethic. We got a set of mostly originals out within three months and we were out playing.”

Diatribe took their cue from English punk-jazzers Pigbag and Rip, Rig and Panic, playing the Windsor Castle and other places, including The Factory, the Glen Innes club France had helped get a liquor licence years before.

The band recorded soon after forming, with sessions at Mascot producing Diatribe’s only recording, the Too Lazy EP on Hugh Lynn’s Warrior label. The recording sessions had another upshot: France was obliged to pay for the studio time by setting up Lynn’s publishing company, Tribal Music.

The publishing venture drew international interest – Herbs were invited to tour in Europe with UB40, but declined when it became clear they’d be expected to pay to play. Bluesman Taj Mahal would later cover a couple of songs from Herbs’ second album, Light of the Pacific. In 2017, France’s work paid back when the TV show Westside used ‘Azania’ in its Tour episode and he collected $2500.

France’s friendship with Mita continued as she worked on Patu!, her film about the tour. With Herbs’ Spencer Fusimalohi, the pair wrote ‘The Treaty Song’ for the film’s soundtrack.

“‘The Treaty Song’ was an attempt to bring it back to New Zealand and write about local issues. It’s not the greatest song in the world, but it’s got quite good lyrics and Merata comes in and does the waiata in the middle – I still find that really powerful when I listen to it.”

Diatribe continued to play live. Greg Johnson and future Headless Chickens vocalist Fiona McDonald joined, and stayed when it evolved into Seven Deadly Sins, a soul band which also featured Wayne Baird on guitar and Dennis “Choc” Tuwhare on bass (after Tuwhare, a pre-Chills Justin Harwood was on bass). Rautjoki’s lithe reggae song on Too Lazy, ‘Dangerous Game’, had another life in the 1990s when it was covered by Jules Issa.

The band dissolved in the late 1980s after France, the law student of the 1970s, finally began practising as a lawyer. “That was the end of it really. That took my creativity away.”

He’s grateful for the way music shaped his life and introduced him to the likes of O’Reilly and Lynn. And he wonders might have been had his friend Fonoti not left Herbs after that first record.

“Herbs were doys, in the words of Howard Morrison – working musicians. Twelve Tribes of Israel had started with Hensley Dyer and Toni was drawn to that, rather than the doy culture of the others, so he was never going to stay. But if he had stayed, I reckon the band would have become a truly international group. He’s written a lot of songs, but those songs he wrote with Herbs are his best work.”

There was a hint of the past in 2017, when France married his wife Hilary Ord. After a ceremony in which the wedding couple performed a song they had written together, the guests weighed into their celebrations. Many of them barely noticed, let alone recognised, the two men who took the stage half an hour later. They were Spence Fusimalohi and Toni Fonoti, performing ‘Dragons and Demons’ one more time.

Visit our sister site

NZ On ScreenMade with funding from

NZ On Air