Not long after forming, Diatribe played to a less-than enthusiastic audience at an Auckland pub. The hotel manager told them he wasn’t surprised at the lack of response. “You’re a university band,” he explained.

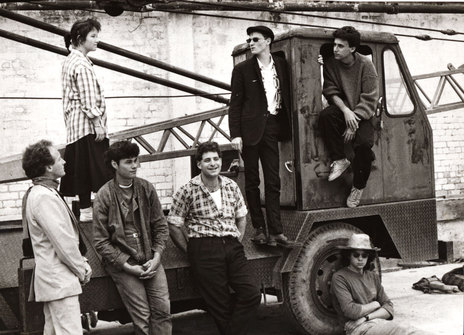

Their low-key approach to being on stage led to suggestions they lacked presence when performing. There was no stage show, no fancy lights. “That’s our greatest criticism: the lack of stage presence,” saxophonist Rafer Rautjoki told Rip It Up in 1983. “Because we’re all from diverse backgrounds we don’t present one single image, which I think is good, but some people don’t.

“Anyway, this might sound selfish but my main interest is the music. That’s the reason for being in a band.” But the music – on one hand easy-skanking Pacific reggae that emphasised their connections to Herbs, and on the other ska and jazz for a dancing crowd – did subsequently win over pub audiences and the Windsor Castle in particular became a friendly stage for them. For bigger shows they’d use the vibes and Rautjoki, the young man who shunned theatrics, would be the centre of attention.

“My main interest is the music. That’s the reason for being in a band” –Rafer Rautjoki, 1983.

The group formed within the ambit of Hugh Lynn’s Warrior Records and Mascot Studios. Co-founders Ross France and Rautjoki originally met through the latter’s mother, film-maker Merata Mita. Rautjoki became the regular babysitter for France and his then wife, and subsequently his friend.

The two friends both decided to learn to play the saxophone in 1981 – and six months later found themselves alongside Morrie Watene in the horn section for Herbs’ 1982 Sweetwaters show. It would be a one-off.

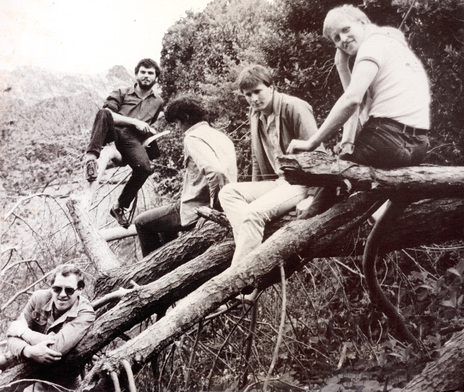

France had helped manage Herbs through their transition from South Auckland covers band to festival act, and wrote ‘Azania (Soon Come)’ for Herbs’ debut album Whats’ Be Happen? but, frustrated by the often unwieldy process of wrangling Herbs, decided in 1983 to form a new band with his friend. They recruited John Berkley, who had been Herbs’ bass player for a short time, along with guitarist Peter Kirkbride and drummer Chris Whyte. Rautjoki could turn his hand to a variety of instruments, including vibes; France also played keyboards.

Rautjoki recalls, “I worked out that being able to play more instruments gave you a bit more variety in the sound. I never had any formal tuition, but my uncles played in bands. My uncle Joe played guitar and my uncle Wahea was a saxophone player. I’d seen photos of them playing.”

The band formed and developed in a busy milieu.

“We’d have band practices at Merata’s house, 16 Cricket Ave in Mt Eden, where Rafer lived too,” France recalls. “It was such a creative place. There’d be a full editing suite in the front bedroom, where people were would be working all night. Zac Wallace was around. It was a great time.”

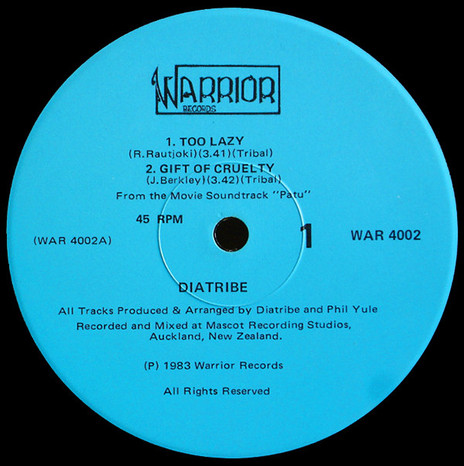

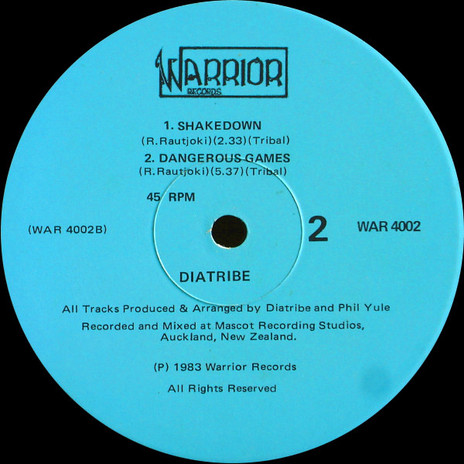

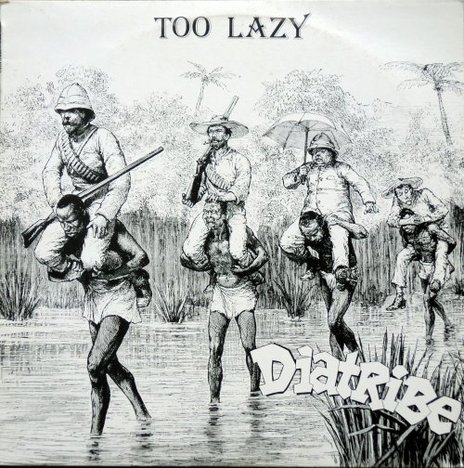

The name Diatribe came quickly (“we were quite pleased with it,” says France), as did the songs and then the EP Too Lazy, which was produced by Phil Yule and released on Warrior in 1983. France, who had a law degree, paid off the studio time at Mascot by setting up Lynn’s publishing company, Tribal Publishing.

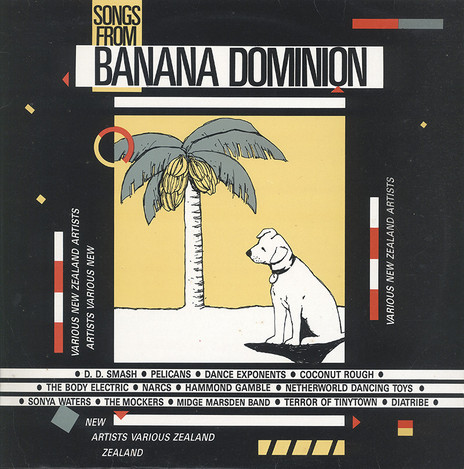

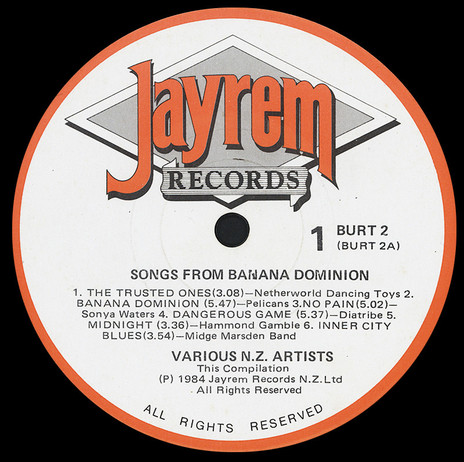

Rautjoki’s ‘Dangerous Game’ was a languidly political slice of Pacific reggae.

The best-remembered song from the EP (in part because it was covered by Jules Issa in the 1990s) is Rautjoki’s ‘Dangerous Game’, a languidly political slice of Pacific reggae that bore a debt to Grace Jones’ ‘I’ve Seen That Face Before’.

“I wrote that song quite quickly and it just came together really simply and easily, as some songs do,” says Rautjoki.

“It was a sort of anti-violence song – the idea was that if you go down that path of using violence then you’re headed down a very risky path. That’s really what the song was about. And I hadn’t heard Grace Jones when I wrote the song! But it is very similar, that Sly and Robbie rhythm. I wasn’t even aware of her when wrote the song. When I hear it, I’m struck by the similarity, but it’s purely coincidental.”

It is the other, more uptempo tracks on the EP that better reflect Diatribe’s live identity. With an ear to the likes British punk-jazzers Pigbag and Rip, Rig and Panic, and an affinity for the ska revival, they played political songs to a dancing crowd.

At the time of the EP’s release France told Garth Cartwright for Metro, “We’re more diverse than just straight reggae now. We’ve got our own flavour that is reggae-influenced. Our problem is that audiences are really cliquey, we don’t appeal to any one set.”

Also in 1983, the Diatribe song ‘Contamination Blues’ appeared on the Propeller Records compilation We’ll Do Our Best – it features the same blend of skittering horns and left-wing politics.

There would be only one more Diatribe song committed to record – although strictly speaking it came from Fofo’anga, the loose ensemble, including Herbs’ Spencer Fusimalohi, that had preceded the formation of Diatribe itself. As Fofo’anga, the group provided soundtrack music for The Bridge, a 1982 documentary about the Mangere Bridge dispute of the late 70s, co-directed by Merata Mita and Gerd Pohlman, and also contributed a track Radio Hauraki’s Hauraki Homegrown ’81 album.

‘The Treaty Song’ was written by France, Fusimalohi and Mita for the soundtrack of Mita’s stunning Springbok Tour documentary, Patu!.

“‘The Treaty Song’ was an attempt to bring it back to New Zealand and write about local issues,” says France. “It’s not the greatest song in the world, but it’s got quite good lyrics and Merata comes in and does the waiata in the middle – I still find that really powerful when I listen to it.”

It wasn’t their only contribution to the soundtrack. It also included ‘Gift of Cruelty’ from the Too Lazy EP, and a distorted version of ‘God Defend New Zealand’, both plucked from 30 minutes of music they’d laid down on Berkley’s four-track recorder and presented to the director. The latter was very much in keeping with what Cartwright described as “an underlying current of humour running through the band … not funny ha-ha, more an acerbic wit that leads them to stamping on sacred ground.”

The band made a deliberate effort to include a message in its songs.

The band made a deliberate effort to include a message in its songs, Berkley told Cartwright. “The words are important, we agonise over them,” he said, laughing. “We’re conscious of them. All our songs deal with serious subjects, yet that doesn’t stop us delivering them in a tongue-in-cheek manner.”

“We were involved in the protests so we have been completely honest with the music,” France told Cartwright. “The film itself reflects what happens on one side of the protest. It is only supposed to show the protester’s view. She hasn’t sensationalised anything, she even removed the percussion in some scenes because she found people were getting excited and involved in the violence and she didn’t want that reaction.”

Work with Mita flowed both ways: with her then-husband Geoff Murphy she helped make a video for ‘Too Lazy’.

The group expanded when trumpeter and vocalist Greg Johnson answered an ad in the paper. Fiona McDonald, later of the Headless Chickens, joined on vocals after Johnson called 95bFM to ask who was singing the station’s jingles. It was her first band.

“Although Diatribe weren’t actually playing the kind of stuff that I was really into at the time, it didn’t matter,” McDonald told music.net.nz in 1999. “I was very young and just super-excited to be singing in a band.”

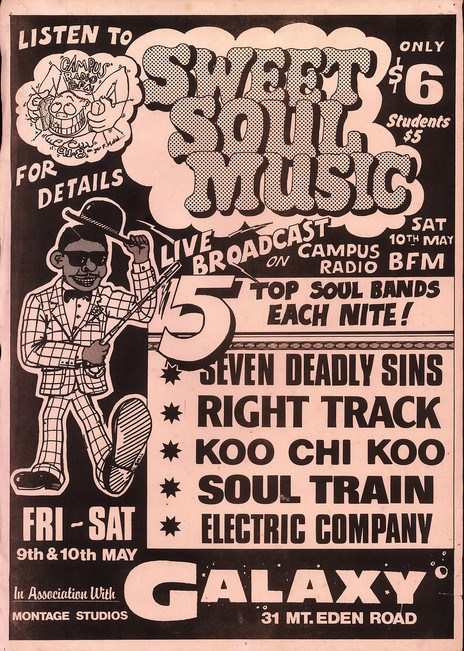

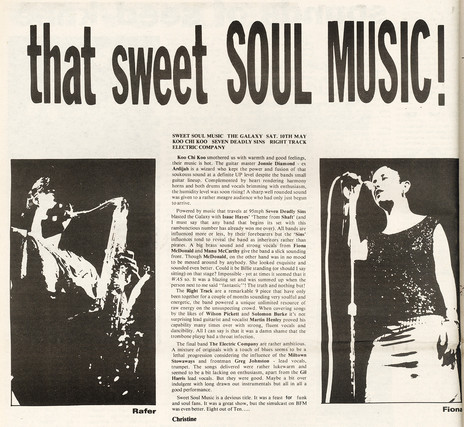

Diatribe split in in 1986 when Whyte, whose drumming was a crucial element of the sound, moved to Australia, then Berkley decided he wanted a quieter life. France, Rautjoki, Johnson and McDonald stayed together in a new, more soul-oriented group called Seven Deadly Sins. Dennis “Choc” Tuwhare joined on bass along with a guitarist called Junior joined, taking the band in a funkier direction. John McGough, who would later go on to become an award-winning brass band player, filled out the brass section.

The new band was as busy as the old one had been, playing the Rumba Bar, Mainstreet and the Gluepot as well as Mt Eden Prison and the Factory nightclub in East Tamaki.

Tuwhare left and was replaced by Justin Harwood, who came from the Big Sideways band, but the group dissolved in 1987 when Harwood left to join The Chills and France finally began to practice as a lawyer. Seven Deadly Sins recordings made at Montage Studios in Grey Lynn were never released. Rautjoki, who now puts his artistic energies into film, says his memories of the two bands and their changing lineups are fond ones. “Everyone got on pretty well. We never really had huge fights like a lot of bands seem to.”

Diatribe had other heavyweight friends in the creative community. Besides working with the film directors Mita and Murphy, they jammed with Bruno Lawrence. “Good guy, creative individual and great sax player,” France said to Metro.

Although Diatribe received accolades from critics for Too Lazy, some isolated recordings and the soundtrack work remain the band’s legacy.