AudioCulture

The noisy library of New Zealand music

Te pātaka korihi o ngā puoro o Aotearoa

Peter Dasent

Yet he says almost all of his musical adventures have been accidental, the result of chance meetings or occasional leaps into the unknown, which are contrary to his nature and upbringing.

Peter grew up in Wellington, in the old green suburb of Karori. His father lectured in chemistry at Victoria University; his mother was the librarian at Marsden College. It was hardly what you would call a rock’n’roll childhood. In fact, he didn’t join his first band until he was in his twenties. He never even set out consciously to become a professional musician, though music turned out to be the driving force in his life and was always somewhere nearby.

He was eight, seated at the dinner table with his parents and sister, when he heard his father, turning to his mother, ask: “So what are we going to do about piano lessons for the children?”

“He didn’t say ‘How’d you like to learn the piano?’, Peter recalls. “It was in this very oblique way, which is probably why I remember it.”

A piano duly arrived and Peter began travelling after school to the other end of Karori to take lessons from a Mrs Gascoigne, learning scales, apreggios and simple pieces written for kids.

There was already a bit of music in the house. His father kept a large wooden trunk full of 78s from his student days in the 1940s. “And he would, like on a Sunday evening, bring out his favourite jazz records. It was mostly white swing bands, but he had some non-jazz stuff as well. He had [Stravinsky’s] The Rite Of Spring on 78s, eight to 10 discs, and I remember him playing that to me.”

Both Peter’s parents played a little piano (“Dad played the same Bach inventions all his life and never got any better”), but the most influential sounds in his childhood would come from the just up the road. Two doors away lived the composer David Farquhar and his family, and the households frequently socialised. So when in 1964 the Farquhars acquired The Beatles’ Twist and Shout EP – a gift, as it turned out, from a student of Farquhar’s, the budding composer Jenny McLeod – Peter heard it and was instantly transfixed. “I’d sit and stare at the cover and play it over and over again. Lennon singing on ‘Twist and Shout’ – I mean, I was 10 or something and I’d never experienced anything like it, you know? And ‘There’s A Place’ – I didn’t think of it at the time as major seventh chords, but there was something about the sound of it. And the doo-dah-doos in ‘Do You Want To Know A Secret’. I was really turned on by it.”

One day Peter’s father, noting his son’s obsession, announced: “Well, I think we might go and see these Beatles”, and took the family to a screening of A Hard Day’s Night. Peter would later overhear his parents muttering about the screaming girls. “My dad was saying, ‘It almost makes you feel ashamed of the human race’. I mean, that was my dad all over. He was very anti any kind display of exhibitionism, or overt display of emotion really.”

As the 60s went on, Peter discovered more pop music he liked “and something in me wanted to play it and find out how it worked. I wanted to know what those harmonies were. I wanted to get it under my fingers.”

From his piano lessons, the Bach he studied helped him figure out ‘A Whiter Shade Of Pale’. “We actually had a harmonium in the house that had come over [from Britain] with my dad’s grandfather, who was the vicar of Karori. It was a terrible thing that I used to pump away with my feet, but I could play sustained notes and pretend I was in Procol Harum, so that was really quite exciting.”

The Bach he studied in his piano lessons helped him figure out ‘A Whiter Shade Of Pale’.

Other tunes, like The Small Faces’ ‘Lazy Sunday’, proved trickier to figure out, but the sheet music could be found at Shand Miller’s. He couldn’t afford to buy it, so he would go into the music shop, study the pages and commit the chords to memory.

A new piano teacher, Gwyneth Brown, helped him decipher a mystery chord in Cream’s ‘White Room’. “She said, what's happening is it’s a C chord, but the bass is playing an A. And it’s like a light went off. So I said, I want to know how this how this works, because I knew there was some kind of system there. It’s like looking at a house and you know that there’s foundations and then there’s something that makes the walls and the roof and they put the windows in and then you’ve got a house. It was as structured as that.

“We must have worked out a couple of other pop songs, but that’s when I started doing things like analysing Bach chorales, and I applied all that to the songs I was hearing on the radio. And that went on for years. I mean, I’m still doing it really. These days I can hear something, I know what it is. Back then I was still nutting it out. But that’s what music was for me. It really excited me and I wanted to know how it worked.”

In 1971, after finishing college, he enrolled at Victoria University to study music, maths and French. “Music was an academic historical survey and analysis, so the first year it was Medieval / Baroque and then Classic / Romantic. In the second year I did composition. I remember we had to write a piece of plainsong and I set the lyrics to ‘Why Don’t We Do It In The Road’, including the extra lines in Alan Aldridge's book, Beatles Illustrated Lyrics – something about ‘right where the dump truck dumped its load’ from memory.”

There were other sounds on campus, too: rock shows in the Union Hall and folk concerts in the Memorial Theatre. He heard Tamburlaine harmonise on ‘Suite: Judy Blue Eyes’, Gilbert Egdell channelling Cat Stevens, Robin Simenauer wailing the blues, and a solo Robert Taylor [later of Dragon] playing a version of ‘Shake Your Moneymaker’ that Peter describes as “frightening. Jesus, I’ve never seen anyone so intense. I looked at these people playing, and I thought, I’d like to do that. But I was quite a shy reserved person, kind of terrified of other people, so it really wasn’t an option. And in a way I was content to just learn stuff on my own. I didn’t have this burning ambition to get up on stage and play. Though I remember thinking it would be great to do that, and thinking I probably could do that.”

He had also begun to explore Indian music, again with a little help again from the Farquhars. “David Farquhar got very interested in the sitar, and there was a guy at Vic who had sitars, plural, and lent one to David. So there in their living room was a sitar. David also had this book by Ravi Shankar called My Music, My Life which at the back had a ‘how to play the sitar’ thing. And of course, I was like George Harrison – you know, ‘I’m gonna learn how to play this’, and so I would sit down in this very uncomfortable position on the floor and put the little plectrum on my finger, which is called a misrab, I've never forgotten that, and began at the beginning of Ravi Shankar's instructions.

“Very quickly I realised that this was not going to happen, but I did actually have a sitar and play it a bit and I loved the sound of it. I also had this album of themes from Pather Panchali, which was a famous film that Ravi Shankar wrote the music for, which I actually saw – my parents took me to it. So that was another kind of musical thing that I suppose was related to jazz in a way – it was people improvising, creating beautiful melodic lines. I think that was the thing about it. It was creating a beautiful line. That's what I liked.”

“At the age of 19 I said, I’m gonna go live in London. I’ve gotta take this deep dive and do something really different.”

At the end of 1972, Peter’s father took a sabbatical at York University, and Peter followed his parents to Britain. “I didn’t really know what I was supposed to do, but at the age of 19 I said, I’m gonna go live in London. It was one of a few occasions in my life where I’ve just gone, fuck, I’ve gotta take this deep dive and do something really different. The complete opposite to the way I was brought up, which was very structured and unadventurous.”

“So I lived in London for maybe 15 months and spent three months with a couple of friends driving around Europe and then I got really homesick and came back to New Zealand. But I heard all these bands that I’d only read about. Procol Harum and Traffic and Emerson Lake and Palmer and James Taylor, all these people. And the occasional sort of weird ones. I’d read about this group called Principal Edwards Magic Theatre and I thought they sounded interesting, so I went along and the opening act was Henry Cow. That was another revelatory moment when I went, are these guys playing something they’ve learned or are they making it up? I genuinely couldn’t tell. And there’s something very thrilling about that.

“I heard some classical music too, Bach’s Mass In B minor which I’d studied at university but never heard live, and a couple of Mahler symphonies. I went to a concert of Indian music at the Wigmore Hall because I'd never heard a live performance on the sitar, and the audience! The sitar player would play a particular line and the audience would go ‘ahhhh’, listening and responding to all these fruity lines.”

He also took classical guitar lessons, though he found that the type of playing that most interested him – the fingerpicking of Bert Jansch and Davey Graham, the acoustic work of Jimmy Page – were ill-suited to his nylon-string classical guitar and technique he was learning.

Returning to Wellington, he continued his musical studies and, having borrowed the money from his parents to buy a Wurlitzer electric piano, took his first tentative steps towards playing in a band. “I’d finally worked up the courage to put an ad in the Evening Post which started out, for some reason, ‘Reasonably sane piano player ...‘ Nothing really came out of that. But then I went to [instrument shop] The Golden Horn, and they had a noticeboard and there was this ‘keyboard player wanted’, so I rang them up and went to see them.

“It was at 220 The Terrace and it was this guy on drums, Tim Datson, that I‘d been to school with and I don‘t think had a career as a drummer; Phil Bowering on bass, and a guy called Dominic Ferry, a long-haired hippie guitar player who could play the opening to ‘Road Ladies’ by Frank Zappa. That was really impressive. They used to do long jams on Santana songs which was okay, but they didn't have any gigs.

“I remember saying, ‘Why don’t we get a singer?’ so it was back to The Golden Horn, put an ad up, ‘Singer wanted’, and who should turn up but Andy Anderson, who was completely the wrong singer for that band. I mean, he could sing ‘Road Ladies’, actually, but he wasn't really interested in singing Santana songs.

“But I said, Who’s your favourite singer? and he said Ray Charles. And he was very into Randy Newman. ‘Guilty’ was absolutely Andy at the time, as he was just getting off the grog. And he was very into Dr John. And these were piano-based songs.”

The ill-matched group never played a gig or even found themselves a name, but Peter and Andy struck up a working friendship. At a Downstage variety show Peter improvised on piano while Andy did impressions of hipster comedian Lord Buckley. Andy introduced Peter to guitarist Andrew Delahunty, and in early 1977 the three began playing as Andy Anderson’s Express, with bass player A K Goss and drummer and future Mutton Bird, Ross Burge, completing the lineup. The group gigged around Wellington and even travelled as far as Christchurch, but Andrew Delahunty was more focused on his university studies and before long had handed in his notice. Peter remembers the conversation about finding a new guitar player because it would change the course of his life.

Andy Anderson said, “What about Fane Flaws as a guitarist?” Peter had never heard of him.

“Andy said to Andrew Delahunty, ‘Well, what about Fane?’ I’d never heard of him. Andrew said, I think he’s probably more into his own music, but give him a call.

“And so the next rehearsal Fane Flaws turns up, and I actually recognise him from Wellington College. He was three years ahead of me, but he’s quite distinctive. He had this white hair, the only kid in school with white hair. And quite distinctive features, not exactly a face that merges into the crowd.”

Delahunty was right: Fane was more into his own music. Andy Anderson’s repertoire of Randy Newman, Dr John and BB King songs held little interest for him. But Fane impressed Peter at an early rehearsal when he brought out one of his own songs, ‘You Should Have Seen Her’, a boogie blues with ribald lyrics.

“The next day, I got a call from Fane and he said, ‘Why don’t you come out to my place and I’ll teach you some more of my songs? Then the next time we rehearse with Andy we’ll know them’. I said, okay, and out I go to Paekakariki, 17 The Parade.

"I lugged my little Wurlitzer piano up there and he put this book in front of me. He opened it up and it was full of chord charts and he said, ‘Okay, play this one’. He’d start to play and sing, and, just instinctively, I kind of knew what to play. ‘Okay, play this one.’ We just went through a whole lot and I’d never encountered anything like that in my whole life.”

Fane’s commitment to Andy Anderson’s Express was tenuous; he already had plans for an original band to realise his own creative visions. But he had found his piano player.

Fane had already spent several years in BLERTA, Bruno Lawrence’s Electric Revelation and Travelling Apparition, though Lawrence had eventually fired him for transgressions detailed elsewhere in AudioCulture. But he had maintained a good relationship with Blerta’s bass player Patrick Bleakley, and had by now patched things up with Bruno who was in the early stages of a film acting career. Fane had Patrick lined up as bass player in his new band, and after trialling a couple of drummers who proved unsuitable, he asked Bruno to join.

Aware that his own idiosyncratic vocals would not suffice, Fane turned to Tony Backhouse, formerly of Mammal and more recently Hired Help, who after a calculated campaign of harassment by Flaws (see the Tony Backhouse story on AudioCulture) agreed to come in on vocals and guitar, bringing with him his partner Julie Needham on backing vocals, and Spats was born.

Peter, who just a few months previously had never played with a band in his life, now found himself onstage with some of the country’s most seasoned musicians. “I was going off musical instinct and Fane’s amazing encouragement. I mean, he’d flatter you as well, but it was a combination of flattery and charm and genuine enthusiasm for what I could bring to his songs. And I remember just being so excited that I was in a band, and we were going to go and play and that's all I wanted to do, play gigs with this band.

“I was going off musical instinct and Fane’s amazing encouragement.”

“Bruno and Patrick – I didn’t really realise what a special thing it was to have them as the rhythm section because it was the only rhythm section really that I’d ever played with. I didn't even know what the parts of a drum kit were! I would just go with it, play something that I thought would fit in, and of course Bruno loved that ’cause he’s a jazz drummer. And so we had a really good thing on stage together and other people used to comment on it.

“I was discovering jazz at that time. Somehow I got this Bud Powell record called The Amazing Bud Powell, there’s two volumes of it, and one of them’s got this tune called ‘In Poco Loco’ and Bruno knew it, of course. It’s got this amazing drum part by Max Roach. Incredible cowbell playing, a Latin kind of feel. Patrick picked it up straight away and we tried to play it. And again, I was just going totally on instinct, but I also went, I need to know how this music works. I could hear stuff going on in these piano lines that wasn't a language that I immediately could play, but I wanted to find out about it.”

Fane, too, had an interest in jazz, particularly the Parisian gypsy swing of Django Reinhardt, which he would approximate on his electric guitar. Spats would divide their shows into brackets, each one in a different musical idiom, complete with costume changes. The first set would be comprised of Fane’s quirky original rock songs, which included such still-unrecorded classics as ‘The Fish Slice’, ‘Three-Pronged Fork In My Heart’ (a 13-bar blues), and ‘The Duke and the Roxy’. Then they would change into tuxedos for an “old-time” bracket, which included some Django Reinhardt and swing tunes of Fane’s, and return after a break for a set of doo-wop songs, inspired by Fane and Peter’s shared love of the Frank Zappa / Mothers of Invention album Cruising With Ruben and the Jets. For this set they introduced themselves as the Crocodiles.

It was an action-packed show, musically and visually, and entirely different from anything else on the New Zealand circuit at the time, which didn’t necessarily work in Spats’ favour. Though they drew appreciative crowds at hipper metropolitan venues such as Auckland’s Island Of Real and Wellington’s Last Resort, provincial pub-goers tended to be bemused at best, at worst openly hostile.

“We just played what we liked, because we thought it was good, and therefore that’s the reason you play. I’ve never had the attitude of, let's put a band together and play Fleetwood Mac songs because people will like it. But I remember at one stage, after we played a few of ours and they yelled out for something, Fane saying to the audience, ‘Okay, here come the pop songs’. And we played ‘Don't Stop’ by Fleetwood Mac and, like, five or six pop songs that were on the charts that were okay. We tried to learn to [Steely Dan’s] ‘Kid Charlemagne’ and it was impossible, but we did play 'Sign In Stranger’. And ‘East St. Louis Toodleoo’, not that that was a huge hit with audiences. We did some Zappa tunes, but again these were not pop hits of the day.”

Bruno was the first to leave Spats, having contracted hepatitis. He was replaced by Stewart Crooks, followed by Mike Knapp, who brought his then-partner Karen Norris to operate lights.

"Mike and Karen tried to get us a bit organised and, you know, have band meetings and stuff like that, which is kind of anathema to Fane. But it just wasn’t happening. We wanted to have a record contract and make records. We had original songs. That’s what bands overseas did. They got signed to Warner Brothers and made albums. Why can’t we do this in New Zealand? Nobody was being signed at the time. The record companies were all just satellites for the American and British companies and the only people that made records were really commercial people like Jon Stevens and Sharon O’Neill.

“And the other thing that happened was punk and we were immediately not in that zeitgeist. Punk bands like the Suburban Reptiles, they all made singles because that’s what all the punk bands did. But the stuff that we liked from that era was Elvis Costello, XTC, Joe Jackson even. People that were writing really classy songs, that had listened to stuff from the 60s.”

By the end of 1978 Peter was feeling disillusioned. “I remember starting to talk about it with Fane, how I wasn’t happy, and he said, ‘I know what the issue is for you. You’ve never left a band.’ And he was absolutely right. I had never left a band.’

So Peter left, though Spats would only play a couple of gigs without him before the whole thing folded.

Music entrepreneur Graeme Nesbitt, recently out of prison, was in the process of setting up the Wellington Arts Centre, a work scheme for artists, which included Peter’s then-girlfriend, actor and singer May Lloyd. Graeme suggested to Peter that he sign up to what was popularly referred to as The Scheme. “I said, ‘What am I going to do?’ He said, ‘You can do whatever you like, I’ll sign you up as a songwriter and composer.’ How good is that?”

With Garth Frost, Dasent devised a cabaret, Stiff Bix, which incorporated skits, dances, songs and a live band.

At the Arts Centre he met another artist on The Scheme, Garth Frost: an actor, singer, lyricist and puppeteer. Peter became Garth’s sound operator as Garth performed a Punch and Judy show with his beautiful handmade puppets. Having discovered a shared love of Bertolt Brecht and Kurt Weill, the pair devised a cabaret, Stiff Bix, which did a season at the Wellington Rock Theatre, incorporating skits, dances, songs and a live band. Peter was pianist and musical director. The core of the band was the Wellington all-women group the Wide Mouthed Frogs, augmented by Bruno Lawrence and Peter Stewart on saxophones.

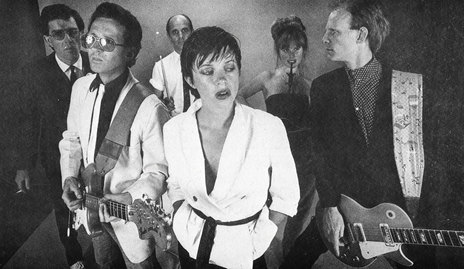

The Scheme came to an end in late 1979, by which time Fane Flaws had come up with a scheme of his own. American record producer and hustler Kim Fowley had come to New Zealand to scout talent and, after hearing a demo tape, summoned Fane and Tony to Auckland to play him their songs. The audition was brutal; Fowley would seldom listen to more than the first few bars of a song before shouting ‘Next!’ But his interest was enough to win them a recording deal and, from the remnants of Spats – with the addition of Wide Mouthed Frogs singer Jenny Morris and, soon after, bass player Tina Matthews – The Crocodiles were born.

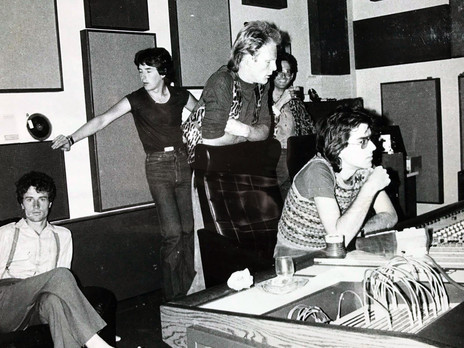

The Crocodiles’ debut album was recorded at Broadcasting House in Wellington, with overdubs at Mandrill in Auckland. It was released in early 1980, and the band began extensive national touring. With the focus on Flaws’ poppier songs (plus contributions by Tony, Peter and lyricist Arthur Baysting), the powerful stage presence of Jenny Morris, and the growing familiarity of their hit ‘Tears’, they were able to draw good crowds to pubs, clubs, even schools.

Yet once again it proved hard to keep the show on the road. Most of the money they were earning was being ploughed back into funding their tours. Bruno was the first to leave, this time to pursue his acting career. Then Fane, struggling to support his growing family, handed in his notice. By the end of the year, Peter and Tina had also quit.

“After Bruno left, then Fane, all the kind of fun went out of it, you know? And I remember saying to Tony, I’m sick of playing songs, I want to play music. And so after our third tour of the South Island or something, I decided I’d had enough.

“Split Enz were just beginning to be really successful and I said to [former Enz member] Mike Chunn, who was our manager, ‘When are we going to tour America?’ and he said, ‘When your fifth album gets to number 57’, or something like that. Like, don't even think about it. So I was just sick of it. I didn't want to be a keyboard player playing parts. I was far too interested in other music.”

After leaving The Crocodiles, Peter joined a number of fellow Wellington musicians, actors and artists as a postie; hosted living room jazz sessions with Patrick Bleakley and Martin Highland, and played standards in upmarket restaurants Plimmer House and Orsini’s. Meanwhile, the Crocodiles (whose lineup now included Rikki Morris, Jonathan Zwartz and Barton Price in addition to Tony and Jenny) had gone to Australia, followed closely by Fane Flaws and family. Soon Fane was back to hatching schemes. Peter would receive postcards from him, tempting him across the Tasman with promises of new creative projects. “And eventually, in September 1981, I thought, What am I going to do? Am I going to stay and live this comfortable but rather pointless life in Wellington or will I just go and see what Fane’s up to and do something exciting? And that’s what I decided to do. A one-way ticket.”

“Fane said to Mushroom, ‘Alright, you can have my publishing but I want a record contract’.”

Largely on the strength of ‘Tears’, Mushroom, the music empire of Australian entrepreneur Michael Gudinski, had shown an interest in signing Fane as a songwriter, along with Tony, Peter and ‘Tears’ co-writer Arthur Baysting. They were duly contracted, paid an advance, and given a Portastudio to make demos. Since arriving in Sydney, Fane and Arthur had been especially prolific. But Fane wasn’t content to be a backroom songwriter. As Peter remembers it: “Fane said to Mushroom, ‘Alright, you can have my publishing but I want a record contract’ and Michael Gudinski said okay. Fane thought he was doing a great deal. But Gudinski just gave him a record contract to shut him up and put us in the studio with this guy, Lobby Loyde, a legendary Australian guitar player who had been in a band called the Coloured Balls, a loud Aussie rock band.

“He'd say, ‘Alright, be there at at nine o’clock tonight’ and at half past ten Lobby would turn up and the first thing he’d do would be to get his dealer on the phone. He'd say, ‘I'll just ring up the dingdong shop’ and he’d say ‘You got a couple of dingdongs there? What? Not even half a chime?’ He'd talk like that and he was always rubbing his nose, coked out of his brain.”

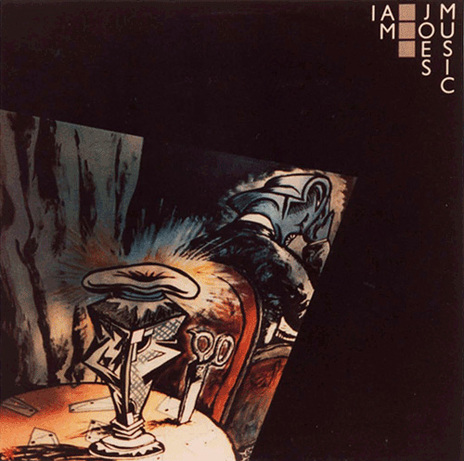

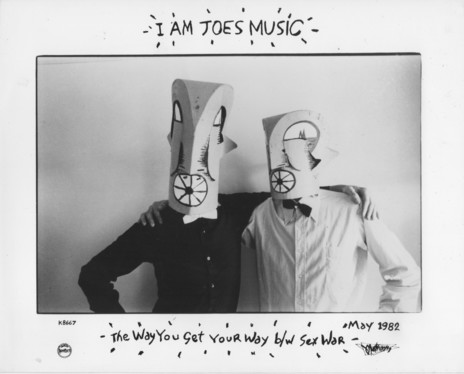

Though prone to such distractions, Loyde was nevertheless enthusiastic about Peter and Fane’s songs and the pair found in Loyde a rich source of amusement. The result was the self-titled album of I Am Joe’s Music, which Fane would proudly boast to be “the worst selling album in the history of Mushroom Records.”

Mushroom had already given Fane the budget to make a video for a single, ‘The Way You Get Your Way’, in which Peter appears heavily disguised in a Flaws-designed mask, and the pair had guested on the national Australian television pop show show Countdown, alongside Jon English, Marcia Hines and Bucks Fizz.

“And then it was suggested we do some gigs, and the one thing I didn’t want to do was do gigs with I Am Joe’s Music, because just Fane and me and a rhythm section I just knew wasn’t going to work. We did a couple and Fane was disappointed by it. It was a recording band, we wanted it to be the Residents, hence the masks. We wanted to be anonymous and just make records. And we almost got to that. We made one. But there were enough songs to make another five.”

While I Am Joe’s Music was failing to ignite the Australian pop market, Peter had been persuaded by fellow New Zealand pianist Mike Gubb [ex-Rough Justice] to audition for the two-year jazz course at the Sydney Conservatorium of Music. “He used to talk about how it was so good, and how he learned stuff all the time, and as a piano player who had this curiosity about jazz I decided that’s what I wanted to do. I wanted to know what Lester Young was doing, but everybody at the time was into Pat Metheny, they just wanted to play this current stuff.

“But the one good thing about it was that once a year you had to do what was called ‘concert practice’, where each student had to organise a half-hour concert. And of course everybody just played Pat Metheny tunes. But I had some music that I’d started to write on my own and I arranged these and got a little ensemble together: flute, trumpet and vibes. And Don Burrows, who was the head of the course – who’s probably Australia’s most famous jazz musician –was really impressed with these compositions of mine. And he said, you know you got into this course as a piano player and that’s fine, but your future is in writing, is in composition. And he said, you should be writing film music.”

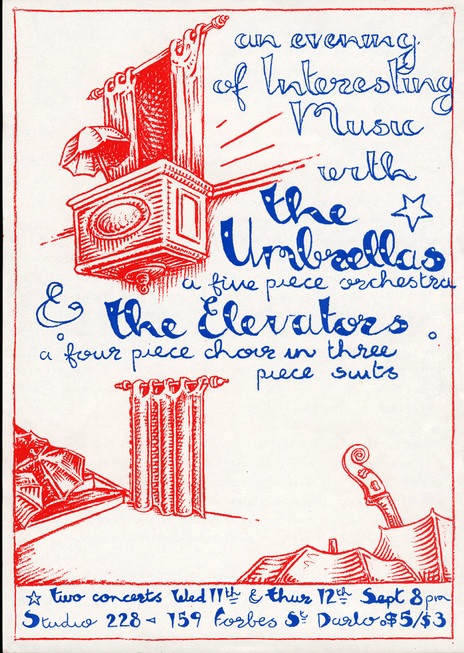

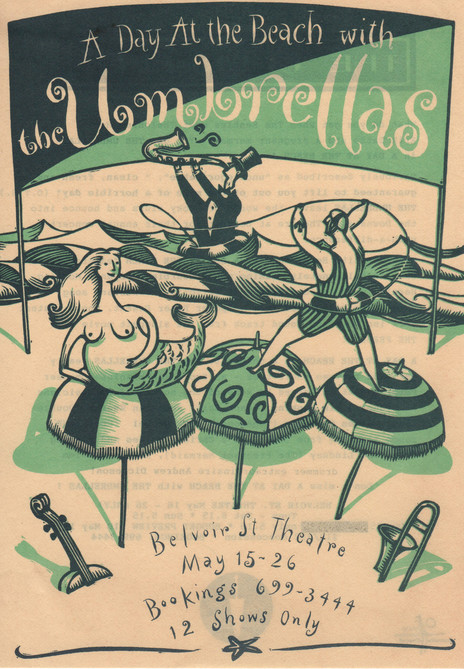

Before long that’s what he would be doing, but the concert practice also led him to form his own chamber ensemble, The Umbrellas, which at various times over the next few years would include fellow New Zealanders Martin Highland, Jonathan Zwartz, Peter Boyd and Christchurch-born saxophone player the late Mark Simmonds. “I wanted to play instrumental music with jazz musicians improvising over it, but not jazz, not the jazz language. Exactly what Zappa did, you know – write some funky eccentric little tunes, and then get really good players to improvise over them. I wanted it to be like Hot Rats or something like that. And it went through various combinations. It got quite jazzy at one point and I was always sort of fumbling around trying to find the best combination of musicians and exactly what it should be. But the Umbrellas made five albums, four in a hurry and then one final one in 2015. And that was my musical focus for the next 15-20 years, the main personal one for me anyway.”

“I wanted to play instrumental music with jazz musicians improvising over it, but not jazz – what Zappa did.”

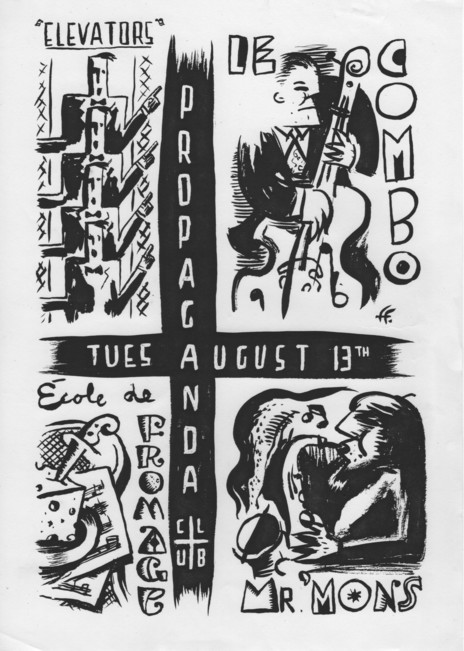

In the mid-80s he also played in Le Combo – a trio with Jonathan Zwartz and vocalist Jane Lindsay, which later became a quartet with the addition of drummer Martin Highland. On a trip to Wellington they played a short residency at The Oaks, with Bruno filling in on drums. “It was quite a well-paid gig for the time. After I gave Bruno the money he said ‘Don’t tell [my wife] Veronica I got this’. Fane reckoned he would have spent it all at the races.”

By the late 80s, Fane had moved his family back to New Zealand and was picking up work directing television commercials. He would sometimes find Peter work creating music for the ads. Peter wrote the music and Fane did the animation for the memorable title sequence for Radio With Pictures.

One day Fane rang Peter to tell him that an up-and-coming Wellington filmmaker named Peter Jackson was making a musical movie with puppets, was looking for a composer who could write songs, and that Fane had told him he knew just the person to do it. Fane persuaded Jackson to fly Peter to Wellington, where he was presented with the script for Meet The Feebles.

“They wanted a song called ‘Garden Of Love’, they had the title. And I said to Fane, ‘Garden Of Love’ has got to be a doo-wop song, and so we wrote this doo-wop song. Then there was a group in there called the Funky Black Eels and they wanted a song that Heidi the Hippo would sing with them, so Arthur [Baysting] and I wrote ‘Hot Potato’. And there was one that was Barry the Bulldog’s operatic aria, and I just took an existing tune and put a whole lot of Italian pasta names to it. How did Peter Jackson approve it? I don’t know, but he did. And I got to work with the actor Mark Hadlow who who could sing ‘high dweezlings’ as good as that guy in the Mothers, and so we put together this amazing vocal arrangement.

“Then I had to do the incidental music. I had this Kurswell 88-note synthesiser that was the current technology at the time, and I just took it into the studio and we went to the first scene and Peter said, ‘Okay, we need this’, you know, and I sort of made something up on the spot, really. We kind of did the whole film like that. And about halfway through, I realised that would be a good idea to do to have a click track! This is film composition 101, but I had no idea.”

The learning curve was steep but the soundtrack was a success and he was asked to score the next two Jackson movies, Braindead and Heavenly Creatures, the latter giving him his first opportunity to write for a full orchestra. “I had the technology to do a mock up of the orchestra on my computer, and I had to get it right because I couldn’t rely on my usual thing of knowing I could do last minute tweaks. I remember going through the whole score with the conductor, Peter Scholes, and being impressed with his attention to detail.”

The acclaim received by ‘Heavenly Creatures’ brought Dasent to the attention of film and TV directors.

The acclaim received by Heavenly Creatures brought Peter Dasent to the attention of film and television directors in Australia. “So all through the ’90s I did television documentaries and children’s drama. Job after job after job. It was just functional music. I soon realised all I had to do was write this music, it wasn't anything that was going to last, I just had to give them what would work with the picture and if the director and the producer approved it that was fine. I would just literally look at the picture and improvise something. That’s how I work. I've got some kind of instinctive ability for that, I don't know why but I have. And I've got the different musical languages as well, from learning classical piano, and my dad’s jazz records, and the Beatles, and all the other kinds of music that I got interested in. I can just grab them and it's just hell of a useful if you’re writing film music.”

Then one day it stopped. “In about 2002 I remember saying to [my wife] Sally, I haven’t got another job after this one, being vaguely worried, and kind of knew that that was going to be the end. And sure enough, it was. It all just stopped because all the directors you work with then become executive producers, they go higher up in the food chain. You know, they've got kids to send to private schools, and they need to earn more money.”

But there were other types of music to fill the gap. In the mid-90s he had produced an album for irreverent Wellington trio When The Cat’s Been Spayed, and was called back by one of their number, singer-songwriter Charlotte Yates, to produce her solo album The Desire and the Contempt.

Over the years he had written a number of children’s songs with Arthur and Fane which had developed into another Flaws-driven spectacle, The Underwatermelon Man: a combined hardback picture-book and CD, featuring such guest performers as Neil and Tim Finn, Chris Knox, Don McGlashan, Bic Runga, Dave Dobbyn and Jenny Morris. The project culminated in a live show, staged at Auckland’s Civic Theatre in 2002, with musicians, singers, dancers and elaborate props and sets, and Peter as musical director.

Around the same time Peter was asked to fill in as pianist on ABC-TV’s PlaySchool, a job he would continue to do for the next 20 years. It drew on his skills as an accompanist and improviser. Though the children’s songs he was writing with Arthur and Fane were deemed unsuitable for PlaySchool, an opportunity arose to write some songs for a character, Mixi the Rabbit, in another children’s show, The Ferals. There were plans for Mixi to make an album, but no sooner had Peter and Arthur written the songs, Mixi was axed from the programme. Peter approached Australian actress and PlaySchool presenter Justine Clarke about making a record of the material instead. “We didn’t have any money,” Peter remembers, “but I had a relationship with a recording engineer who had done all the mixing for my screen music up to then. So I said, alright, I’ll do the arrangements, Justine can sing, Rob can record, we’ll spend a few hundred dollars for a day with some musicians to do the backing tracks, and then we'll have it. So that's what we did.”

Justine Clarke’s album I Like To Sing was released in 2005 through ABC and became an Australian hit, selling platinum and winning an ARIA for Best Children’s Album. Over the next decade Peter would produce a further four albums with Justine Clarke, mostly comprised of songs he had written with Arthur.

He also began to tick off projects that had been simmering on the back burner, sometimes for decades. His love for the music of Italian composer Nino Rota had begun in the early ’70s when he heard Rota’s theme for The Godfather, and grew when a Wellington cinema ran a Sunday night programme of Fellini films. (Rota was the composer on all 17 films Fellini made before the composer’s death in 1979.) Over the years Peter had transcribed an arranged various Rota scores. In 1999 The Umbrellas commemorated the 20th anniversary of Rota's death with a concert of Nino Rota’s Fellini film music in Leichhardt (Sydney’s Italian district) and shortly afterwards recorded this music for an album, Bravo Nino Rota. In 2003 Peter was awarded a Churchill Fellowship to research Rota’s music, which included travelling to Italy and the US to interview relatives, colleagues, pupils and friends of the composer, and examine Rota’s archives.

He had often thought about making a solo album of his instrumental piano compositions, “and always chickened out at the last minute. I’d book the studio and then go, I’m not ready for this. Finally I had to book somewhere overseas in order to make myself do it.

He had often thought about making a solo piano album, “and always chickened out.”

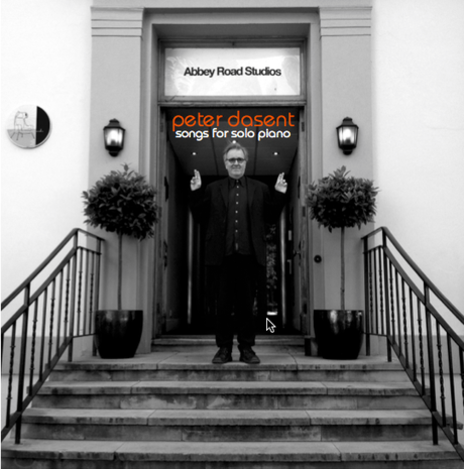

“One of the problems with recording a solo piano record is you want to know what the piano is like. So I googled studios and listened to their online demos of their pianos, and didn't like any of them. In the end I asked [New Zealand-born engineer and producer] Nigel Stone, and he said, ‘I hear there's a good Bosendorfer at Abbey Road.’

“I've always liked Bosendorfer pianos, and I thought, if this one’s at Abbey Road it’s going to be good. It was a bit of a risk but, you know, I thought I’ll go with Nigel's opinion and I'll go with the reputation of Abbey Road. It cost a bit, but it didn’t cost any more than recording at the ABC [in Sydney]. They charge a bomb recording on one of their Steinways.”

Which is how, in 2013, Peter ended up recording at Abbey Road. This is, of course, where the Beatles made the vast bulk of their music, including that first EP that had changed the course of his life almost half a century before. He recorded in Studio 3, the smallest of the Abbey Road studios, where the Beatles had often gone to mix their recordings. Much of Revolver was made there, as well as Pink Floyd’s Dark Side Of The Moon. Of the three studios at Abbey Road it is the one that has undergone a redesign since the days of the Beatles and, as Peter says, “these days is just like any well-appointed recording studio.

“However we were allowed into Studio 2 when the orchestra there were on a break. That was exciting and had a definite vibe. It still looks the same as all the photos – white walls and the famous staircase. Then in the corridors were the inevitable photos on the walls but also they were lined with old tape machines. I also got to peek into Studio 1 which is massive, and was being set up for a ‘function’ later that day, also a common use of the place these days, so there were people setting up trestle tables and waiters and stuff. A little odd, a little sad too I suppose. I couldn’t imagine ‘A Day In The Life’ in there, or even Cilla and Burt.”

In 2016 Peter got a call from former Spats drummer Mike Knapp, who was stage managing a 40th anniversary tribute to The Last Waltz, the famous farewell concert of The Band. The promoters had arranged to bringing Garth Hudson, The Band’s brilliant keyboardist, to New Zealand as a star guest. But as Garth was nearly 80 and frail, it was decided it would be wise to have backup on hand in case he got tired. “In fact it was me that played the whole show,” Peter remembers, “with Garth doing a couple of spots – ‘Chest Fever’ obviously, and ‘The Weight’ and a couple of songs with [his wife] Sister Maud.

“The highlights were just hearing him play – anything, on stage and especially at rehearsals when he played a lot of piano. After the last show in Auckland there was a party at the Town Hall and Garth climbed up the steps and played the Town Hall organ. Emboldened by a few wines, I did the same and played a bit of Nino Rota. When I came down the steps I sat next to Garth and he leaned over and asked ‘What Fellini film was that from?’ He knew his music.

“He was very reserved and quiet but friendly when you spoke to him, although his soft drawl was hard to understand – except when we rehearsed the intro to the song ‘Chest Fever’, after his epic solo intro, and I became aware of him calling out to me ‘Turn off the vibrato!’ Fortunately I was able to dive into the music software and do exactly that. Whew! I’m very untechnical with that sort of stuff.”

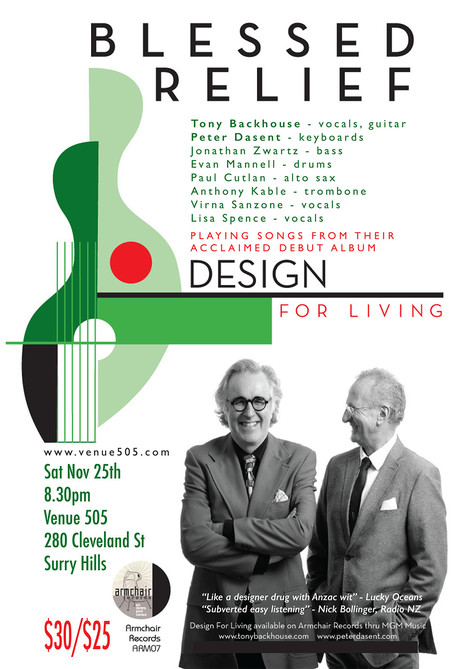

Peter released his Abbey Road recording, Songs For Solo Piano, in 2013 on his own label, Armchair Records. In 2015 came Lounge Suite Tango, the first album of original music in 20 years from The Umbrellas, followed two years later by Design For Living, a collaboration with Tony Backhouse under the collective monicker Blessed Relief, which the pair had been working on intermittently since the late 80s. Then there was We Disappear by The Bend, the name Fane, Tony and Peter had begun using for their projects as a trio. This album had been started by Fane in 1986: a collection of Sam Hunt poems set to music. Peter not only played keyboards throughout but also set one of the poems, the succinct ‘Meeting An Old Love’, which closes the album. We Disappear was released just a month before Fane’s death in June 2021.

Fane Flaws left a number of unfinished projects, with instructions for their completion, which Peter expects will keep him busy for a while. There are two more illustrated book and song projects for children along the lines of The Underwatermelon Man. The pictures and typography are finished for the first one, The Boy With the Flaming Hair, but the songs still need vocals. Another, The Girl With No Reflection, is less complete but Fane suggested that the unfinished illustrations – just pencil sketches – should be used. There are also two more unfinished Bend albums of original songs by Fane, Tony and Peter. The first to be released will probably be Modernisation Means Trousers “if Tony and I can find a time to sit down together and listen to all the tracks and work out what has to done in terms of edits and overdubs.”

ANOTHER PROJECT IS A CHILDREN’S MUSICAL, AND DASENT CONTINUES TO WRITE SONGS AND PLAY GIGS WITH JUSTINE CLARKE.

Another project is a children’s musical called Jungle Hideaway, the brainchild of Australian film producer here David Elfick, for which Arthur Baysting and Peter wrote the songs, and Arthur contributed to the script.

Peter continues to write songs and play occasional gigs with Justine Clarke, but not children’s songs this time. “She started out as a jazz singer so we do some jazz standards and a couple of songs that Fane and I wrote the last time he came to Sydney in early 2020,” he says.

He sometimes plays as a duo with New York expat alto saxophonist Phillip Johnston, leader of the Greasy Chicken Orchestra, focusing on Thelonious Monk tunes, and occasionally sits in with Petulant Frenzy, a Sydney band dedicated to performing the music of Frank Zappa. He also has his own radio show, One Size Fits All, which he has hosted since 2013 on community station Eastside Radio 89.7FM, using Zappa’s music as the jumping-off point for a genre-busting playlist. And after 22 years he’s still on call for PlaySchool, to which he brings the same sensitive, enquiring and humorous spirit that informs all the music he makes.

“I can improvise over anything that’s happening on the screen and know the musical language of the show. If we’re doing, say, a classic nursery rhyme, I’ll often think ‘what would Randy Newman, or Dr John, or Steve Nieve play on this?’ I try and be as creative as possible. That keeps it interesting and alive for me.”

Visit our sister site

NZ On ScreenMade with funding from

NZ On Air