Don Richardson

“We had a hell of a night with the Yanks who just about tore it down and fell out of the Cabaret about three in the morning. He’d drunk a bit, but I didn’t because I was a kid. He said, ‘How’re you getting home?’ I told him I’d get a taxi, but there weren’t any available, so he said, ‘Okay, hop on’ and he dubbed me home from the Maj right out to Kilbirnie. I thought that’s got to be part of history – a drunken peddler taking this kid home from the Maj in the middle of the night.”

The “Maj” (or Madge) was the Majestic Cabaret in downtown Wellington, and the merry peddler was the band’s classically trained, hard-case pianist, Alan Wellbrook. The kid in question was Don Richardson, a prodigious Wellington-born musical talent who started playing reeds professionally while still at Rongotai College. This was VJ Day, the war was over, and the whole town was partying. Not surprising that everyone was excitable and a little under the weather.

The Don Richardson Band, pictured at Caroline Bay, Timaru, in the summer of 1955-1956. At the back, Vern Clare and Graeme Saker. In front, Mike Gibbs, Johnny Williams, and Don Richardson. At the piano, Bob Barcham. At various stages, Clare, Williams, Richardson and Barcham worked at Begg's, Wellington. Gibbs, who played jazz and classical trumpet, joined the NZSO as a teenager.

Photo credit:

Chris Bourke collection

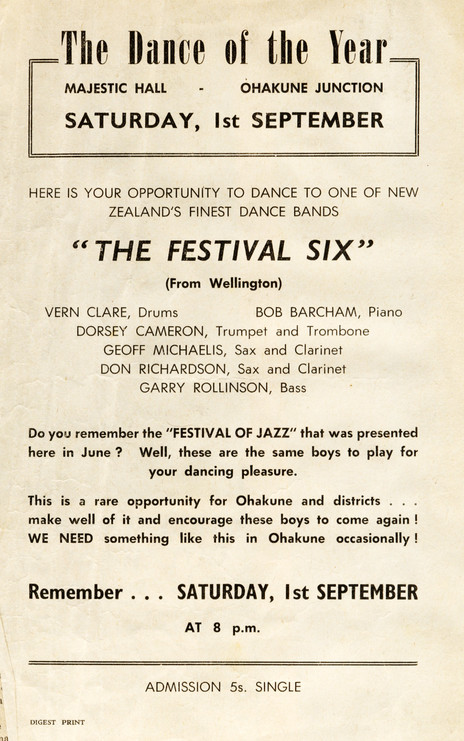

Don Richardson's Festival Six goes on the road to perform in snowy Ohakune, 1956.

Photo credit:

Don Richardson Collection

Don Richardson on saxophone, with singer Marise McDonald, performing on a Pacific cruise, early 1960s. The pair would marry in 1968.

Photo credit:

Don Richardson Collection

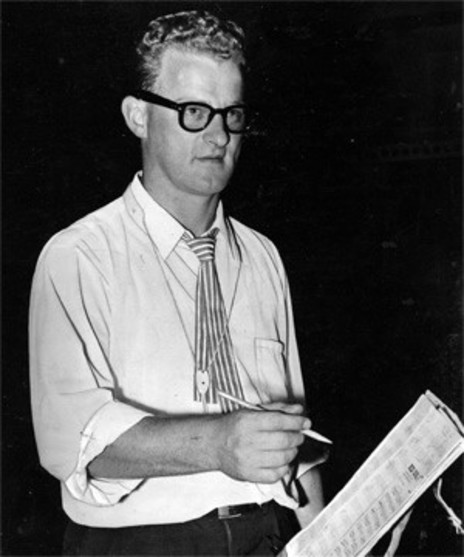

Don Richardson, rehearsing his arrangements for a Wellington jazz festival, March 1956.

Photo credit:

Evening Post/Don Richardson Collection

Don Richardson plays the saxophone (at left) in this sketch of four members of the Kiwi Concert Party, c. 1950.

Photo credit:

Don Richardson Collection

An early combo led by Don Richardson, he is sitting third from left, playing saxophone.

Photo credit:

Don Richardson Collection

After the Second World War, the Kiwi Concert Party broke box-office records in Australia. In this lineup, Lew Campbell conducts, among others, saxophonist Don Richardson, bassist Harry Unwin, and pianist Jack Roberts.

Photo credit:

Don Richardson Collection

Marion Waite, expatriate US singer based in Wellington in the late 1940s and 50s.

Photo credit:

Don Richardson Collection

Bob Barcham taught countless pupils the piano in Wellington over many decades. He performs here at the Wellington Town Hall, December 1956. Don Richardson at right.

Photo credit:

Don Richardson Collection

A side view of a band led by Don Richardson playing a theme night (the butchers' ball?) at the Majestic Cabaret, Wellington, 1950s.

Photo credit:

Don Richardson Collection

A young Don Richardson on saxophone.

Photo credit:

Don Richardson Collection

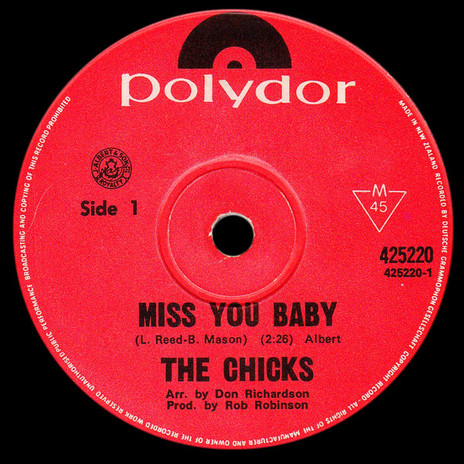

The Chicks - Miss You Baby (Polydor, 1969). Arranged by Don Richardson.

The Majestic Cabaret band performs at the Mobil ball, Wellington, early 1950s. Don Richardson on saxophone.

Photo credit:

Don Richardson Collection

Don Richardson, late 1940s, when he was a member of the post-war Kiwi Concert Party.

Photo credit:

Don Richardson collection

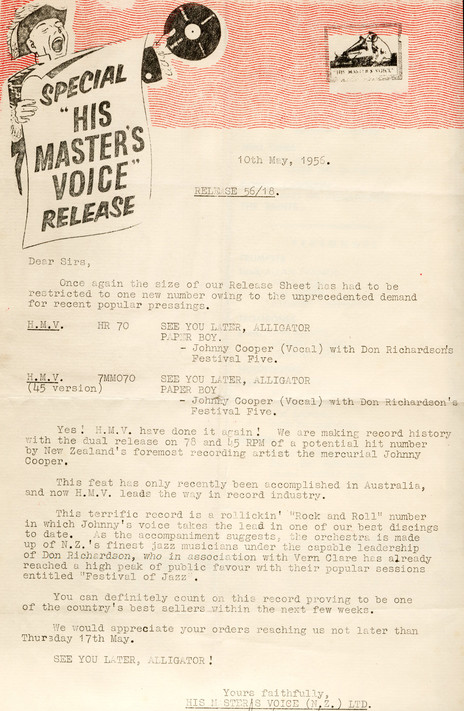

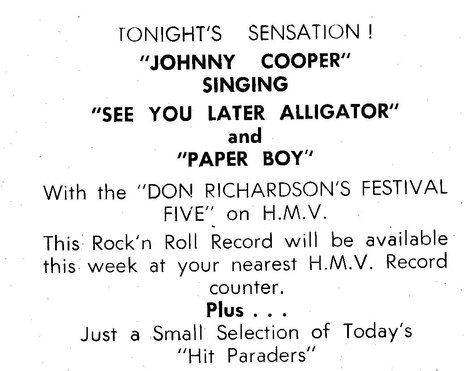

In May 1956, Johnny Cooper’s version of ‘See You Later, Alligator’ was the first record to be simultaneously released on 78 rpm and 45 rpm discs in New Zealand. This is HMV's release sheet.

Photo credit:

Don Richardson Collection

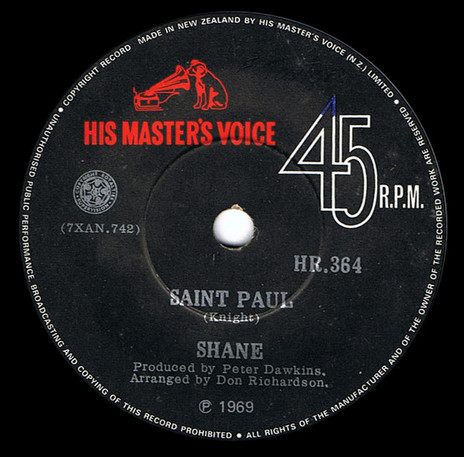

Shane performing Saint Paul (arranged by Don Richardson) on the Loxene Golden Awards, 1969.

Johnny Cooper and Don Richardson at the Wellington Town Hall, December 1956. Lawrie Lewis sitting at right.

Photo credit:

Don Richardson collection

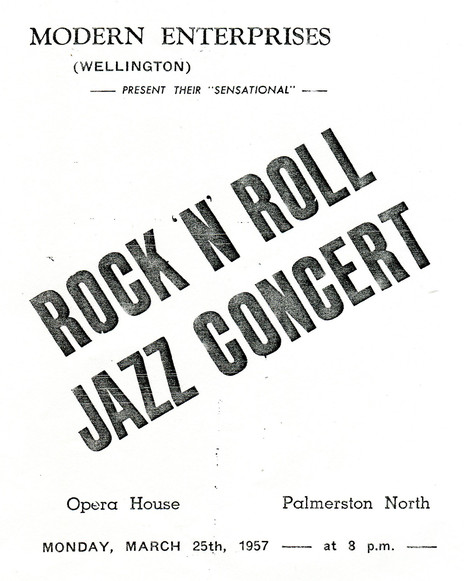

Rock'n'roll - and jazz - comes to Palmerston North, 25 March 1957. On the bill were Johnny Devlin and Johnny Cooper, plus jazz musicians such as Don Richardson, Vern Clare, Bob Barcham, and singer Marion Waite.

Photo credit:

Don Richardson Collection

Allison Durbin - Games People Play (HMV, 1969). Musical direction by Don Richardson, produced by Howard Gable.

Wellington, c. 1955: band leader Don Richardson discusses arrangements with trombonist Dorsey Cameron, John McIvor at left.

Photo credit:

Don Richardson Collection

Vern Clare, trumpeter and flamboyant drummer, was a partner of Don Richardson in Modern Enterprises, which ran the 1950s festivals in Wellington. He also owned Clare's nightclub.

Photo credit:

Don Richardson Collection

Shane - Saint Paul (HMV, 1969). Produced by Peter Dawkins, arranged by Don Richardson.

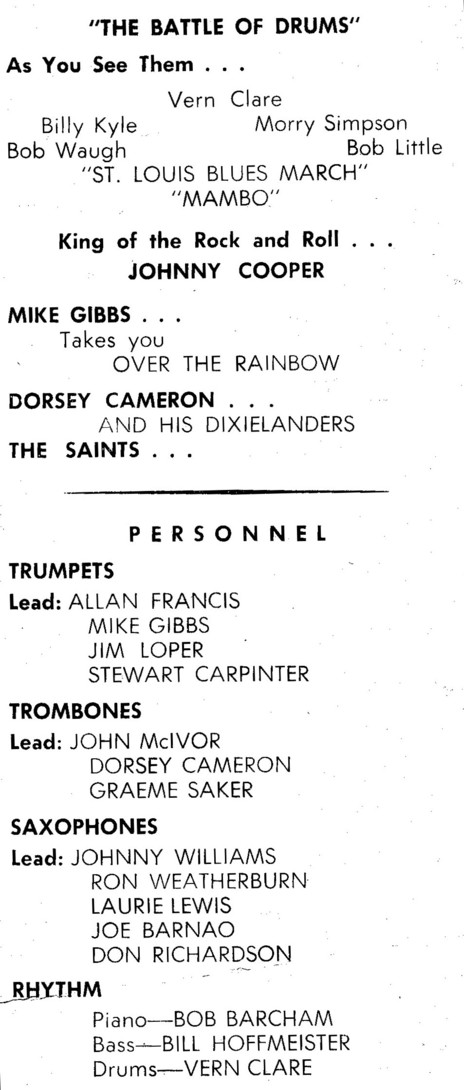

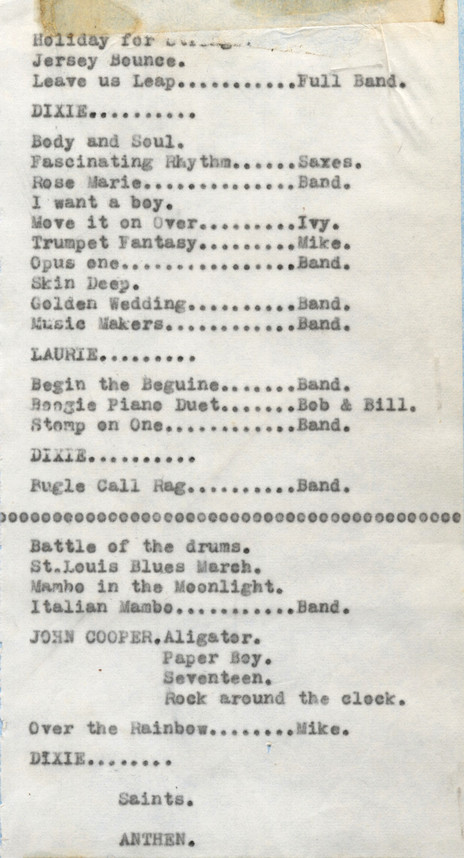

Personnel for the Sixth Festival of Jazz, Wellington, 14 May 1956: Vern Clare performs a "battle of the drums", and an early appearance by Johnny Cooper, "the King of the Rock and Roll".

Photo credit:

Don Richardson Collection

Don Richardson as a boy, top row, second from left, performing with Roy Baker's Piano Accordion Band c. 1940.

Photo credit:

Don Richardson Collection

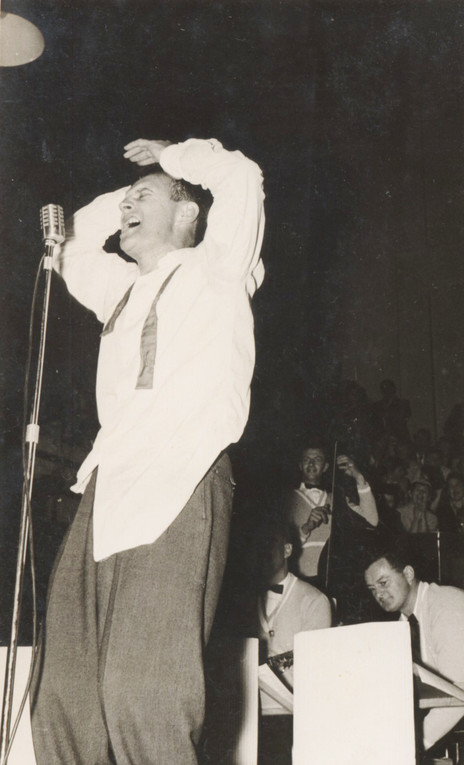

"John" Cooper brings rock'n'roll to the Sixth Festival of Jazz, 14 May 1956.

Photo credit:

Don Richardson Collection

An emotive vocalist - possibly Johnny Summers, Johnny Richards or Johnny Borg - with the Don Richardson Big Band, at the Wellington Town Hall, 1956.

Photo credit:

Don Richardson Collection

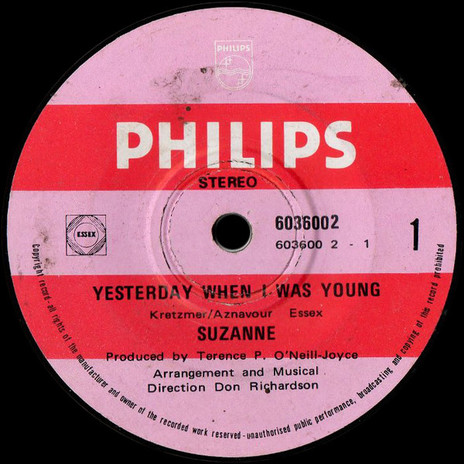

Suzanne - Yesterday When I was Young (Philips, 1971). Produced by Terence O'Neill Joyce, musical direction and arrangement by Don Richardson.

An advertisement for the May 1956 single (with Don Richardson's Festival Five) See You Later Alligator

Discography

Labels:

HMV

Polydor