“When I was doing C’mon, the guy who was in charge of the Broadcasting Corporation, the Director General, was Gilbert Stringer – an old radio accountant. His view of television, and he said it in fact, was that television is just … radio with pictures. That was the attitude and I had the pleasure of enshrining his remark into a television title which is still here of course!”

The person responsible for that [1987] remark is Kevan Moore, a former producer with the NZBC and the creative driving force behind some of New Zealand’s most innovative pop programmes.

Kevan Moore, producer of C'mon, with his star host, Peter Sinclair. A 10-minute interview with Moore discussing his long television career can be viewed at NZ On Screen.

New Zealand, 1963. If the quarter-acre pavlova paradise isn’t a reality, it’s certainly the image. The National Party is in power and Keith Holyoake is Prime Minister. Our greatest worries are foreign – will Great Britain join the EEC? – while domestically the royals are on a swing around the country. Television is in its infancy.

The newly reorganised NZBC has been in operation for barely a year, broadcasting 28 hours per week, with commercials on three of those evenings. Switch on your black and white TV, relax and watch Dr Kildare, Bonanza, Hancock’s Half-Hour, or In the Groove – a local pop programme produced in Auckland’s Shortland Street studios by Kevan Moore.

Looking back at those early years, Moore reflects that for him, “Music was the dominant interest, both professionally and socially. When I went to work in television in Australia, that was transferred into visual terms with a programme called Bandstand, which was a model of the American Bandstand programme.”

Moore returned to New Zealand in 1961, to work on entertainment programmes with groups such as the Howard Morrison Quartet before moving on to In the Groove in 1962. “There were a number of records being produced in the early days in New Zealand so we – Stewart Macpherson and myself – worked on this format which was called In the Groove, obviously because we were working from a record base. That in turn was a model of a programme done in Britain called Jukebox Jury, where a jury of people voted on the popularity of a particular record. So that is how the first of our pop programmes started.”

During those early days of television, New Zealand was beginning to experience the first tremors of a worldwide pop revolution, led in part by the Beatles. I asked Moore whether he thought TV was responsible for introducing that revolution into this country – or whether it was responding to what had already taken root here.

Watch: footage of rehearsals for a 1965 Let’s Go episode, shot on standard 8mm film by technician Clyde Cunningham.

“I think when we went on a bit from In the Groove and did Let’s Go in about 63, there was a social revolution happening; in fashion, accents, internationalism. It was all happening at the same time and music was part of that, particularly with people like the Beatles and the Rolling Stones and the early type of pop groups who had cut through a whole load of social and age barriers, and TV was right at the inception. So we started this programme which was a musical current affairs if you will.”

Let’s Go marked the beginning of Kevan Moore’s collaboration with Peter Sinclair, then a young Wellington disc-jockey hosting the Sunset Show for 2ZB. Sinclair was integral to the show’s success: cool, hip, and professional. Moore claims that “without Peter they wouldn’t have had the magic because Peter is probably the best person in the country to introduce an entertainer, in the way he was able to build a performer who was perhaps unknown, and give them an immediate lift.”

Let’s Go went out live from NZBC’s studios in Wellington. Each week a hundred or so teenagers were brought in to mob and dance around the stars, with Wellington group The Librettos forming the basis of the show.

In 1964, Moore returned once again to Sydney, to work on entertainment and current affairs programmes for Channel Ten. He wasn’t seen in New Zealand again until 1966, but the efforts of that year burst on to a bewildered nation’s screens in 1967, with C’mon. The peak of the Moore/Sinclair collaboration, C’mon sold to the nation’s teenagers a new gospel of style.

“When I got back [to New Zealand] there seemed as though there was a gap for a programme that perhaps had, I think, more of an American influence. Let’s Go was British in a way: it was based on the Mersey sound. Times had moved on of course. We’re talking about it being two or three years after Let’s Go had finished and a shift had, in retrospect, moved from Britain to the US – because at that time I think we were moving into flower power, San Francisco, and Haight-Ashbury.”

TV is known for its ability to create stars. According to a Peter Sinclair quote, he and Moore deliberately set out to create stars. “Oh yes, it was true of the Let’s Go days, C’mon, and Happen Inn – because there weren’t any mass stars. The biggest stars in New Zealand in terms of TV in those days were the continuity announcers and the newsreaders. We used to work very cooperatively with the record companies and with entrepreneurs so that if there was somebody who had been discovered in a talent quest say, whom a promoter wanted to push, and who we saw had potential, then we did. I can recall Sandy Edmonds, who was one of the main stars of C’mon, was one of Phillip Warren’s discoveries. We sort of built her into a big star. On the other hand there were people who were already established who we got behind.”

Much of the material used on the show were covers of overseas recordings. “There wasn’t much indigenous music writing in New Zealand at the time and also we were structured like a hit parade programme.” But Moore did see a growth in New Zealand artists writing their own material. “Yes they were starting to, particularly around the late 60s. If something came along that had been locally written and composed then it got exposure.”

C’mon - watch the complete, last remaining Series One episode, 1967

C’mon did create stars – Mr Lee Grant was a teenage sensation in 1967, as were The Chicks, Shane, Tommy Ferguson, and Ray Columbus. But lesser known groups were also given exposure through C’mon: the Hi-Revving Tongues, The Human Instinct, Larry’s Rebels and Le Frame. C’mon was a mainstream pop show that, while specifically catering for a teenage audience, would also appeal to the whole family, so that it was not surprising that – as many diversified away from pop into more solid hybrids – the programme would encounter difficulties. “At that time, we were starting to get into rather uncomfortable areas,” says Moore. “C’mon was a TV programme that went on at 5.30 every Saturday night so we always had to bear in mind quite a lot of young audience watching, and we did start having great problems with lyrics that were alluding a bit too obviously to sex and drugs.”

I asked Moore what were the reasons for the demise of C’mon, reminding him of a quote he made some years ago where he said, “Pop shows, as distinct from light-entertainment shows have to be some kind of social documentary.”

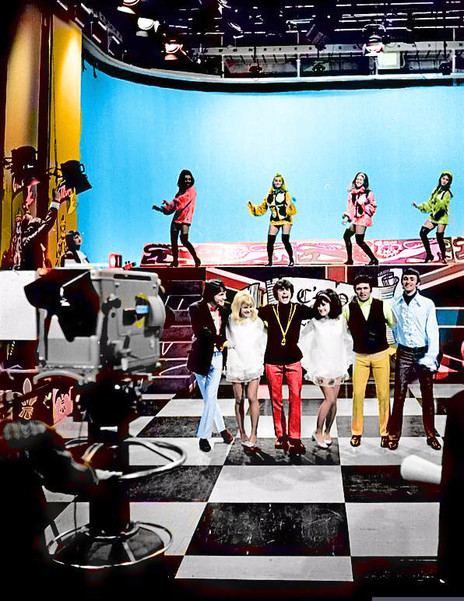

On the set of C'mon (L-R): Shane, Suzanne Donaldson (The Chicks), Ray Columbus, Judy Donaldson (The Chicks), Tommy Ferguson, and Ray Woolf. - colourised image from the Grant Gillanders collection

Moore responds, “Sex was part of the pop scene and it was very valid to show it on that programme. We got to the stage where we were ignoring a lot of songs or changing the lyrics. Now I was very uneasy about doing this sort of thing, but it was obvious that at the time the public wouldn’t put up with the content of those songs. So by mutual consent we axed the show.”

Television took the leading role in presenting specific pop performers, but as music came to reflect the more realistic concerns of the period, whether it was Vietnam or drugs, it made programmes like C’mon redundant.

“It probably did, if I remember rightly. We by and large based the programme on a maximum of three-minute songs, preferably down to two, so there was plenty of variety, movement, action. I think songs started getting longer and longer, there was one in particular that went on for 10 minutes or so, and it was impossible to get anything out of it and still portray the song: ‘MacArthur Park’ I think it was. The programme was supposed to reflect the times in some way or other, and if it couldn’t do it, then possibly the main reason for it existing had gone.”

After the demise of C’mon, Moore went on to produce Happen Inn, a family-entertainment styled programme that was cross-generational and mainstream. Looking back, Moore doesn’t recall any programme being mooted that would have catered for a C’mon-type audience – at least until Free Ride in the early 70s, which was hosted by Ray Columbus.

After the change to colour in 1974, Free Ride became an experiment for Moore “to get to know colour … We deliberately did things that, perhaps visually, we should never have done – just so that we could get to know our craft.”

So did Moore consider that those programmes had encouraged an interest and growth in New Zealand music? “Well, they must have done – as a byproduct. Because in those days, in the very early days, anything that used a lot of New Zealand artists was regarded as being an inferior programme. One of the major things that was achieved was raising the popularity of New Zealand programmes and New Zealand artists.”

Of those programmes – In the Groove, Let’s Go, C’mon, and Happen Inn – few complete copies exist today. In the case of In the Groove, none at all. It’s a frightening loss of musical history.

As producer of those programmes, Moore has an attitude shaped by the requirements of the day. “We, as a whole group, were really conditioned to live TV, so in a way it was a bit like today’s newspapers, tomorrow’s fish’n’chips. We regarded the whole thing as ephemeral. You either saw it at the time or it’s gone.”

This first appeared in Book of Bifim (1987) and is republished here with permission.

Kevan Moore died on 1 January 2024.

--

Links

C’mon, Let’s Go – C’mon hits the road