“I remember seeing Mark Williams performing on Ready To Roll singing the hits of the day. He had the flares, the sequins, and a bit of make-up. I thought, ‘Oh wow, he’s really cool’. It was before gender bending was really a thing. I don’t know anything about him personally, he might be a straight guy, but it was really great that he embraced that campy look and I take my hat off to him for doing that at the time. Then you had Freddie Mercury, Elton John, George Michael, though I think Boy George was the only one that yelled out that he was gay.”

Stanley’s parents could see he loved music and were aware that the Dunedin Sound was creating a buzz, so encouraged him to move to the city. He got a flat on George Street and his flatmate Andrew Brough (Straitjacket Fits, Bike) taught him how to play guitar and the basics of songwriting. This led to Stanley forming his first band.

“We were called The Gaps because we all had gaps in our teeth. People used to change the P on the posters to a Y, so it said ‘gays’. That was the sense of humour back in the day. We did lots of live shows at the Empire, the Oriental and other venues around town. Around 1988, Andrew told me that Straitjacket Fits were moving up to Auckland. I thought that I may as well have a go up there too. Me and Andrew got a flat in Parnell, then I started writing some new songs.”

Making it in Auckland

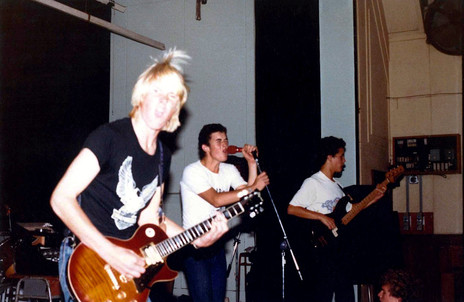

Stanley found an ad in a music instrument store posted by a “gothy keyboard player” who was looking to form a band. This led him to Michael Caulfield and the pair formed Big Explosion. They entered the 1989 Battle of the Bands and got through to the final but found themselves playing their “campy disco” in a line-up of hard rock bands. They came last but caught the eye of one of the judges.

In a 1989 Battle of the Bands, Big Explosion came last but caught the eye of Mike Chunn

“We were backstage, and this man came over to ask who’d written our song ‘Shy Shy Jenny’. I told him that Mike and I had. It turned out it was Mike Chunn. He said, ‘Oh my god, you’re amazing songwriters, come up to CBS on Monday, I want to work with you.’”

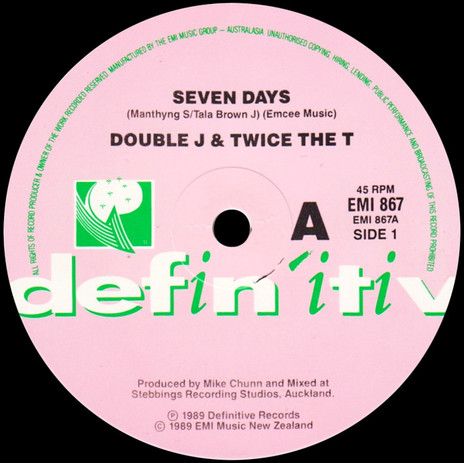

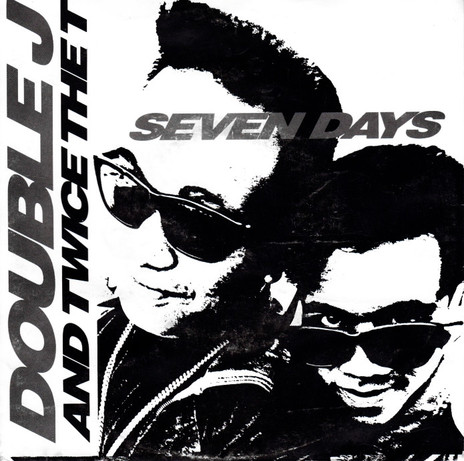

Chunn had started his career as a member of Split Enz and Citizen Band, before moving on to become a linchpin of the local music industry. He was in the process of starting his own label Definitiv with his old bandmate Tim Finn. They’d signed rap duo Double J and Twice the T, who had a hit with a remake of ‘She’s a Mod’ (‘Mod Rap feat Ray Columbus’). Chunn asked Stanley to help with a follow-up single, which led to him co-writing and singing on the single, ‘Seven Days’. The song had keyboards by Caulfield and singing by Debbie Harwood (When The Cat’s Away), and it reached No.7 in November 1989.

The rap duo’s ongoing success led to them being hired to front a government water-saving campaign (“Drips Waste Water”). Stanley was again brought in as a co-writer – ‘Def To Be Green’ reached No.4 in April 1990.

Harwood had provided vocals with Stanley for the song’s hook, but she was away on tour and couldn’t appear in the music video. Stanley instead called in Jacinda Klouwens from Fatal Jelly Space – a band he adored, as well as being close friends with many of its members. He often found himself spending time with guitarist Frankie Hill.

“I was hanging out with a lot of lesbians at the time,” Stanley recalls, “they were more my crew than the gay boys. There was a lesbian club called Midnight in Albert Street and I preferred going there to play pool than going to the Queercase [Staircase]. It was rough and the Beastie Girls were there, there’d be fights. It was an amazing time.”

Stanley was also keeping busy as a live performer. He sang in funk group Cactus and brought his sense of humour to their gigs (“this next song is called ‘Carpet’ – it’s about a shag pile”). Yet when it came to entertainment, it was hard to top his eight-piece band, Beautiful.

“We’d do big campy live shows and all land in a spaceship. We’d all wear costumes, it was all very glam. Everyone knew if they came to a show they’d have a great time.”

In the 1980s, “Gays were unpopular and the whole AIDs tragedy was going on”

However, it could be a difficult time to be a gay musician. “Gays were unpopular and the whole AIDs tragedy was going on. People were still getting sick. It was weird. The only other gay musicians were Rupert E. Taylor [Warwick Wakefield] from Bird Nest Roys, who was later in Headless Chickens, and Arthur Tauhore from Bump’n Ugly [later singer in Trasch]. We were all mates. Arthur was living in Wellington, but we’d all gig together. We’d arrive at gigs and it’d be like ‘ew, yuck, the gays have arrived’. I’m sure that was said about us because we were troublemakers anyway.”

Mike Chunn was still keen to have Stanley involved in the Double J and Twice the T project and asked whether they could use the song ‘Shy Shy Jenny’ next. Stanley told him it was too personal and instead suggested that he and Caulfield release it as a duo instead.

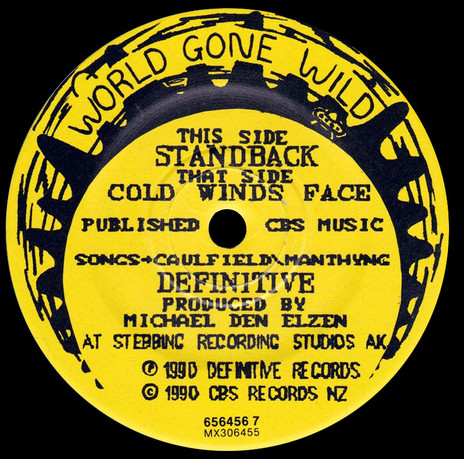

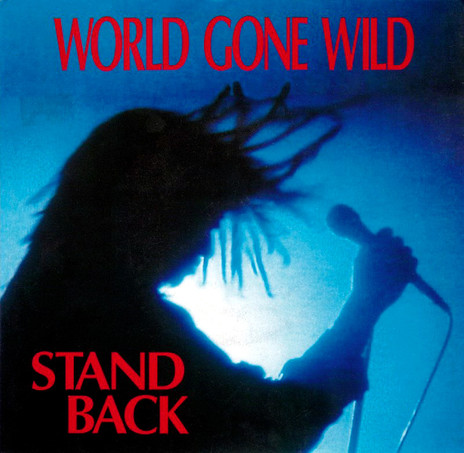

World Gone Wild

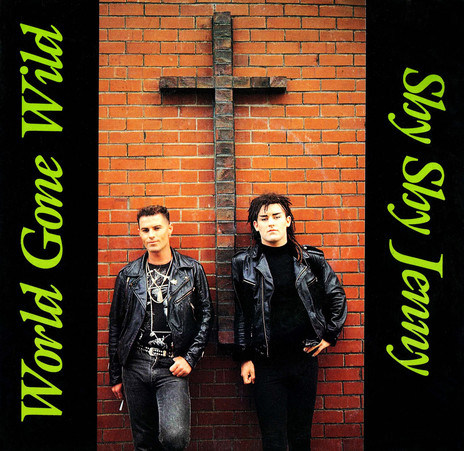

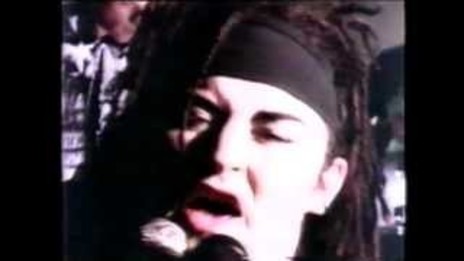

There didn’t seem any point reviving the name Big Explosion since the other band members had gone on to other projects, so Stanley and Caulfield took the name World Gone Wild. Caulfield could sequence the beats and write the keyboard parts, but they needed a producer. Tim Finn suggested his housemate in Sydney – Michael Den Elzen from Phil Judd’s group, Schnell Fenster. He would not only be able to produce but could also play the bass and guitar parts.

Their first single was the song that drew Chunn to them in the first place, ‘Shy Shy Jenny’, which was inspired by a dream.

“I was living in the Big House in Parnell with 20 other people,” says Stanley. “In the next room was Jenny Fuller, who I became friends with. I had this dream that she had died, then I’d gone to the funeral and met her mother. It felt very real, and I woke up crying. The next day I wrote it along to an instrumental that Michael had given me, so it came very easily. I just described the dream I’d had.”

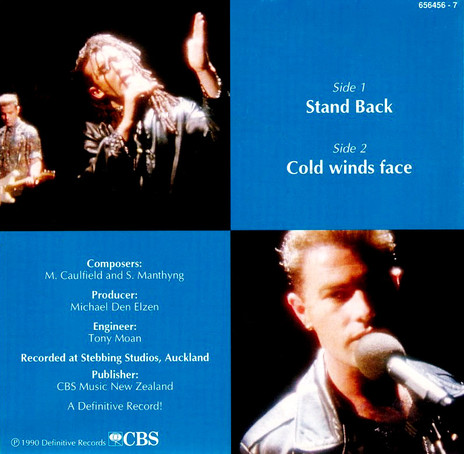

The song was catchy as hell with dramatic keyboards by Caulfield, atmospheric guitars by Den Elzen, and a grooving rhythm track that gave it some forward momentum. It was a difficult time for local music to get on the radio, but it gained decent airplay and dipped into the Top 50, hitting No.47 in September 1990.

Their next hit came about through equally left field means.

“I’d watched a movie with the actress Barbara Stanwyck, where she was living below a mountain. Me and Michael had put together a band and we were in the practice room, recording our ideas on a Walkman. He played the riff and I just yelled out ‘Barbara Stanwyck, Stanwyck, the mountain is calling’ but I thought – people won’t even know who she is! So I changed it to ‘Baby, stand back, stand back’. It just took 10 minutes to write, but it felt like a nice and catchy little pop song.”

“‘stand back’ took 10 minutes to write, but it felt like a nice and catchy little pop song”

Building on their previous success, the song hit No.10 on the charts in May 1991. Meanwhile ‘Shy Shy Jenny’ had been nominated for an APRA Silver Scroll Award. Nonetheless, Stanley did sense some homophobia in the industry. He didn’t receive a nomination or even an invite to the music awards, despite having written four charting hits (three of which made the Top 10).

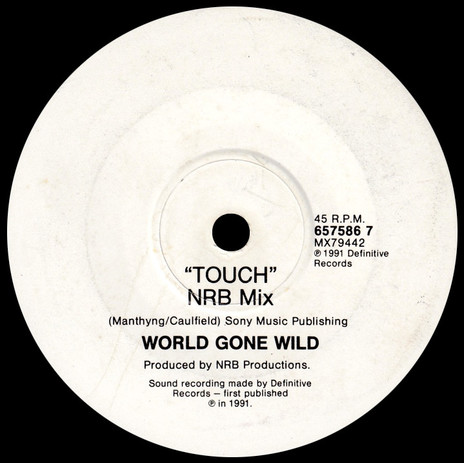

The music video for ‘Stand Back’ featured a trio of female backing singers, but the recorded parts were sung by Crystal Jade, while the other songs on their self-titled debut album featured Suzanne Lynch (The Chicks, Cat Stevens). To promote the release, Mike Chunn suggested releasing a new version of one of the songs as their next single. ‘Touch’ was remixed by Mark Tierney (Strawpeople) and Rex Visible (NRA), with hopes that it might make World Gone Wild sound more like the electronic pop acts coming out of the UK at the time (such as KLF). However, Stanley was beginning to lose enthusiasm for the project.

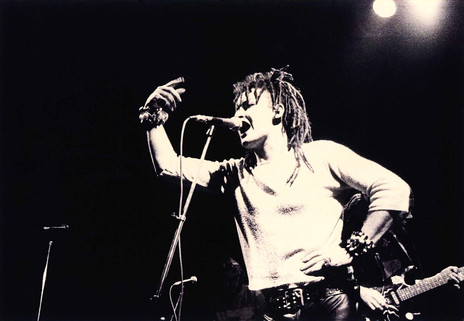

“We’d started demoing songs for a second album with Malcolm Smith from Fan Club. I was distinctive looking, so I started getting hassled a lot in public, which became really annoying. Sometimes people would say nice things and other times they’d say horrible things, but either way it made me a bit paranoid. I just said to my boyfriend at the time, ‘I don’t think I want to do another record, I’m not really enjoying doing this commercial music.’ So we went up to live in London for a while. I shaved off the dreadlocks and wiped away the make-up, and nobody hassled me anymore.”

Stanley and Caulfield parted ways, with Caulfield going on to play in goth act, Winterland.

The Love Gang and beyond

Stanley’s next group was Stan and the Love Gang, who quickly gained a reputation as one of the most entertaining live acts in Auckland.

“What I loved about the people in that band was that I would come up with all these stupid ideas and they’d just say, ‘Alright then’. They were all straight guys but didn’t mind it being campy. Rachel Groover did the vocals with me, and she always encouraged me to bring in as many silly ideas as possible. I’d say, ‘let’s make the music slow right down’. Then me and Rachel would move in slow motion for that section of the song. Everyone would be on board with me. I loved their open-mindedness.”

Their energy as a live act took them on tour throughout the country, though Stanley did sometimes find that audiences weren’t ready for them.

In hawera, a member of the audience jumped on stage and bashed Stanley in the eye

“Love Gang was on a tour with Crash and we played Hawera in Taranaki. We weren’t well known so we went around town trying to promote ourselves. We went to the supermarket and gave the checkout girls our flyers, so they all turned up with their boyfriends and it was a big crowd. Next thing you know, the Love Gang have all stripped down to their speedos. The girls in the crowd loved it, but the boys hated it. They started yelling out, ‘fucking faggots’. I had the microphone, so I was louder than them and yelled ‘go fuck yourselves’. I couldn’t really see the crowd because of the stage lights but suddenly one of them leapt onstage and bashed me in the eye. Knocked me out. The next night we played Wellington and it seemed like a great story, so I left the make-up off that eye to ensure everyone could see the massive shiner. I pointed to it and said, ‘We played Hawera last night!’”

One of the highlights of the Love Gang’s four-year run was a tour throughout the country supporting The Village People. Stanley was blown away to be performing alongside this set of gay icons.

“It was the original line-up. The only person who had changed was the cowboy, so there was Felipe and Glenn and all the rest of them. They were all gay aside from the lead singer Ray, so we sent the promoter a write-up saying we were a campy, alternative band who were gay-fronted. Finally the gayness worked to our advantage! We played two shows in Auckland, then Wellington, and lots of weird places throughout the country. Seven dates in all. They were lovely to us and were really cool guys. They did like to party afterwards. We’d go to a bar and they’d say – ‘this is the code to get free drinks’ – so we had heaps of fun.”

As the members of Love Gang got older, they found that other priorities came in the way of being able to play together and the band folded. One of their final shows was playing in the afternoon on the last day of the Gluepot. They were in the downstairs bar which happened to be filled with a rough crowd of old regulars, including members of the King Cobras gang. The Love Gang kicked on with their show and were just launching into a rare cover song – the disco hit ‘Born To Be Alive’ – when all hell broke loose.

“I saw the big fluorescent lights above the pool table start shaking and next thing you know it turned into a riot. Bottles and glasses were flying everywhere, pool cues were swinging. I said to the band, ‘Run!’ So we stopped playing, left our gear in there, and everyone started trying to get into the hallway to get back out onto Ponsonby Road. The police showed up and it ended up on the 6 o’clock news that night. My mum knew we were performing there, so she rang to check I was okay. I said, ‘It was great, I loved it! We played ‘Born To Be Alive’, Mum!’”

at the gluepot, with members of the King Cobras present, all hell broke loose

Stanley moved to Karitane near Dunedin where he got a job on the television show, Queer Nation. His friends Libby Magee and Nettie Kinmott were hosting the show and asked him to be their South Island correspondent. Stanley wanted to prove that being gay didn’t always mean “being in drag on the back of a float going down Ponsonby Road.” Instead, he wanted to show that gay people were just as likely to be doing everyday jobs in the middle of nowhere.

He and husband Steve Field then lived in Kerikeri for 10 years and Stanley stepped away from the limelight. Yet gradually his inspiration to make music came back. Field was a “computer whiz” so bought a keyboard and taught himself Ableton so they could start making music together. They spent a year writing music then moved to Dunedin and started doing live shows, with all the flamboyance of his previous bands. Field was rechristened Stevolicious and they released three albums as Manthyng, with Lady Manthyng (Tahu MacKenzie) becoming another key member.

Stanley then moved to Whanganui where he formed eight-piece band, The People. The group was short-lived, but played some decent shows, including supporting The Chills at the local Opera House. Stanley was just resigning himself to quitting music once more when he met his old friend Michael “Harry” Harallambi (The Exponents) at a party. It wasn’t long before they were writing new music as Bog Queen and roping in Debbie Harwood to provide vocal contributions via email.

These days, Stanley is reticent to show friends some of the World Gone Wild videos, though he’s proud of their legacy.

“When people ask me about World Gone Wild, I put on the ‘Stand Back’ video because the make-up wasn’t so full on in that one. I stupidly played my current boyfriend the video for ‘Shy Shy Jenny’ and he said, ‘If I saw you and you looked like that, I’d run a million miles.’ I tried to tell him that it was just how we looked at the time – it was the 80s! But when I look back, I’m proud that I did what I did. I think it was really important for there to be a gay figure in New Zealand music and I’d do all of it again in a heartbeat.”