AudioCulture

The noisy library of New Zealand music

Te pātaka korihi o ngā puoro o Aotearoa

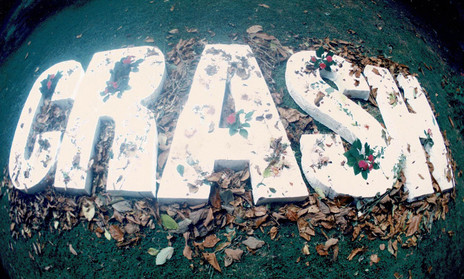

Crash

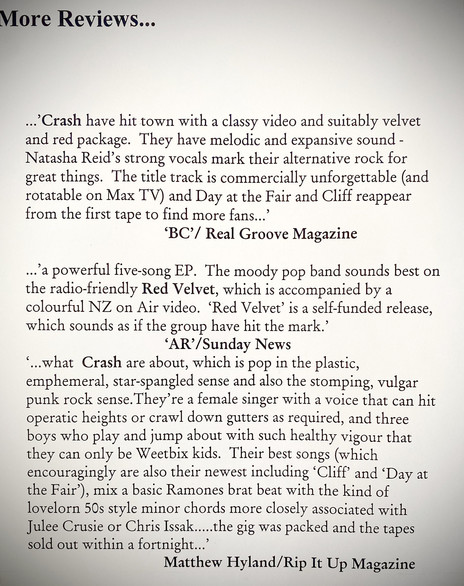

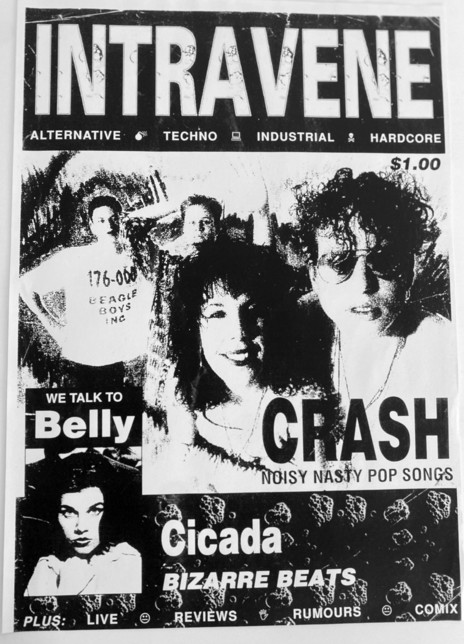

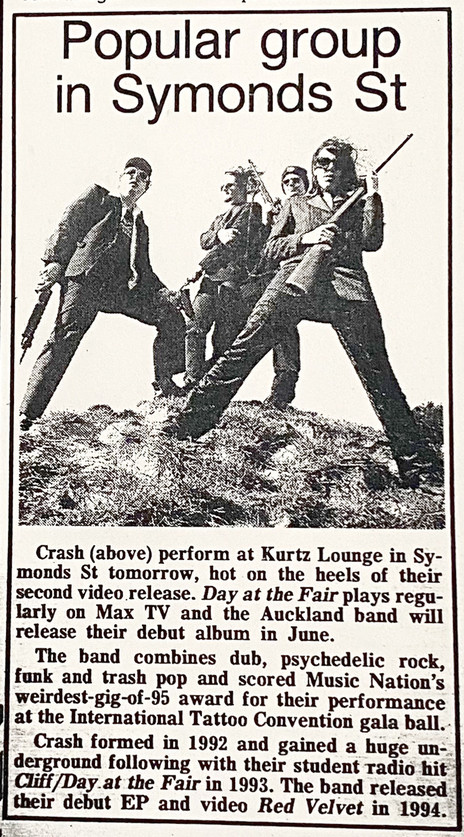

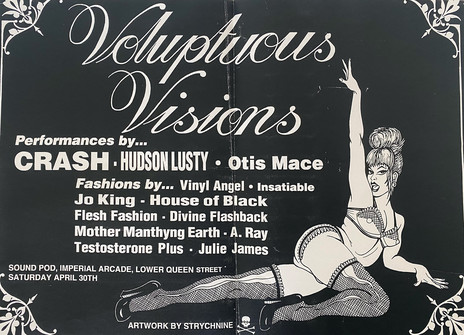

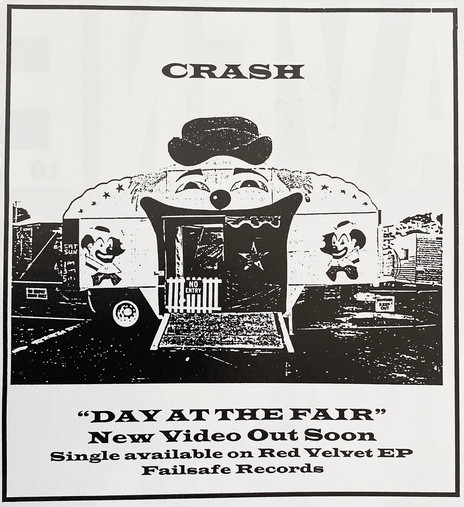

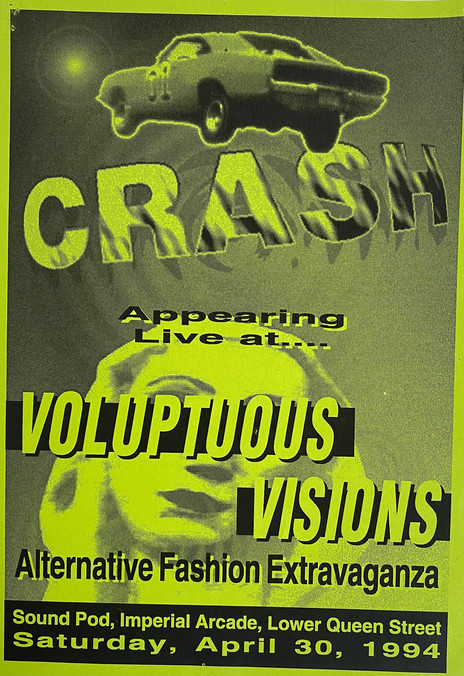

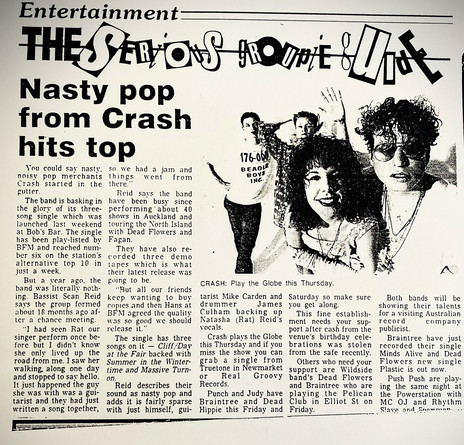

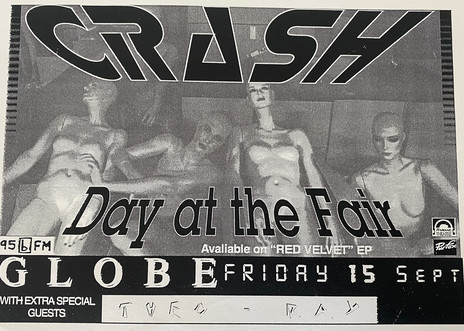

Formed in 1991, Crash hit student radio with their single ‘Cliff’/’Day at the Fair’ reaching the top spot on the bFM Top Ten and their video ‘Red Velvet Sofa’ holding the No.1 slot on Max TV for nearly four straight weeks. They played everywhere from the New Zealand Tattoo Convention in Auckland to Mountain Rock, Sweetwaters 99 and Auckland clubs such as Pelican and POD.

Fronted by singer Natasha Reid, they were distinctive in a landscape of young men with guitars and their diverse, smart and well-crafted songs reflected that. They looked set to break out, but their debut album recorded at Revolver Studio never appeared and, disheartened, the band broke up.

And that would have been it – another band that did the hard yards and was forgotten – until 2023 when Rob Mayes of Failsafe Records remastered their singles and the lost album tracks.

Mayes released the self-titled 17-song collection on CD in an elaborate gatefold cover in November, mostly for the international market. But within a fortnight of its release, the Crash collection landed in the New Zealand music charts at No.4, between Coterie and Stan Walker, 24 years after the band went their separate ways.

Theirs is a story worth telling, unique but also not unfamiliar.

As with many bands, the first line-up of Crash came together through friendships, chance encounters, mutual interests and people from very different musical backgrounds.

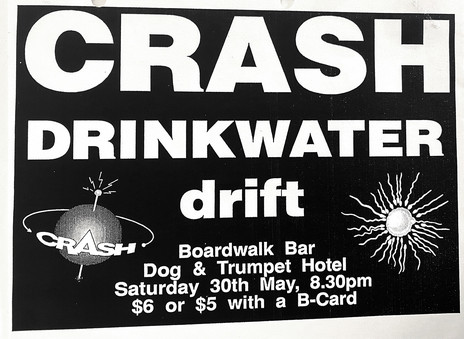

Natasha Reid (now Taylor) and Mike Carden – the sole constants in Crash’s nine-year career and friends to this day – recall what happened in the lead-up to the first live gig in 1992 (as The Logan Girls) at Auckland’s Dog and Trumpet, now the Dogs Bollix.

Natasha, who met Carden through mutual friends in 91, was in the metal band Mistameana, “with Joel Facon who went on to form Subtract and now more recently, Anvil Hammer. Before I met Joel, I couldn’t find guys to play in a band with me. Joel and I cut our teeth on Auckland’s live circuit together as Mistameana. Mike was playing guitar with a band called Cage of Angels.”

She says to Carden, “You were never misogynistic and had no problems picking up a guitar and playing with me.

“I’d met Sean [Reid] who was in The Honeymoon Killers when Mistameana played at the Gluepot, for one of Mark Wallbank’s Aural Asylum events. Sean got the three of us together to jam and the stuff we together did felt really promising.”

“We could have been Ratt or Cinderella or those sorts of glam-metal bands,” laughs Carden.

Carden acknowledges bassist Reid (no relation to Natasha) as instrumental in shaping their distinctive sound: “We could have been Ratt or Cinderella or those sorts of glam-metal bands,” he laughs, “but we wanted to be as tight as we could be.

“Sean is the loosest bass player in the world – I mean that in the best way possible – because he gets into a groove and pumps it out and as a lead guitarist, I could just mess around on top of it.

“Sean was the engine-room and Natasha was gifted at singing on top of anything we played. Then drummer James Culham [from Bad Boy Lollipop] came in and suddenly with Sean, we had a rhythm section.”

Carden notes they’d all come from different bands so had been through the cycle at least once, in his case through bands on Auckland’s North Shore, “all that scene which came out of Northcote College and Westlake Boys where everyone was into guitar bands.

“We were this weird anomaly, and we’d play at a Battle of the Bands and Cactus Jacks and every band was five dudes with a Pearl Jam-style vocalist. Metal had split between LA glam-rock and the precursors based on bands like Saxon. I loved those bands, and Knightshade, but they were super-uncool.”

Their comfort zone was the famous Five Bands for Five Bucks nights at the Powerstation where the likes of Push Push, Dead Flowers, Bad Boy Lollipop, Braintree, and others, made their name alongside Deep Sea Racing Mullets, Uncle Pete’s Garden Shed and more short-lived bands.

Natasha – whose background could not be more different from the metal and hard pop she was playing – was a seasoned musician when she arrived into what became Crash.

“I did my first songwriting in the bedroom at home and learned a bit of guitar at primary school but never ventured beyond that. I wrote my first published song at 11. My uncle is folk musician Mike Reid, who often played at Poles Apart in Auckland, so I did my first ‘spots’ there with him. My uncle was my first collaborative songwriter, and I also co-wrote a couple of songs on his 1987 album Rough Diamond [which was given an expanded digital reissue in 2021].

“I was surrounded by talented folk musicians like my uncle, Martha Louise and Cath Woodman who were influential on me, I was a little ‘folkie’ in the making!”

Natasha attended Marist College in Mt Albert and was steered in the direction of classical music: “I like the sound of it, and I still sing that stuff at home sometimes to work out the pipes.”

Natasha still sings classical music at home sometimes “to work out the pipes.”

“A fun fact here is the Marist Singing Cup,” interjects Carden. “Natasha had won it three years in a row and her mother won it before her, so it was an ‘in the family thing’. Natasha was going for a record fourth win, no one had ever done that, and this upstart called Lucy Lawless entered and won it!”

Natasha laughs: “Lucy’s a talented actress of course and was a year ahead of me at school. We were both in our school production of The Mikado, and Lucy was Katisha, the unintentional villainess and I was Yum-Yum one of three happy little schoolgirls. So, there you go, we were typecast even back then!”

With that in her background and a natural love of storytelling, it quickly fell to Natasha to be the songwriter in Crash and the immediate result was something very different. She looked for inspiration beyond the love and/or rage of their guitar-rock peers.

Their song ‘Castrato’ which opens the newly minted, albeit belated, Crash album, is a striking slice of art rock – “Do you not love ‘art-rock’?”, she laughs. “I love that description of this song.”

It sounds like nothing else from that period in New Zealand music. It includes a dramatic sample from an operatic song, ‘Piango Gemo’ (‘I Weep, I Sigh, I Suffer’) and was inspired by the movie Farinelli which Natasha had seen at the Italian Film Festival. “It is about Farinelli, the world’s last castrato [a boy singer whose testicles are removed so his voice remains high]”.

“It’s a very dark film. The whole song is about him and his relationship with his brother. It wasn’t his choice to be a castrato. I recommend the movie, dark but beautiful and the operatic piece is one I learnt at school.”

One of the band’s most popular songs was ‘Red Velvet Sofa’ which has had many speculating on its meaning: “Inside my veins, inside my head, voices calling me, they’re coloured red”.

Allusive as it may seem, the song has a more comforting and resonant meaning for Natasha. “It’s about our little practice room which I found incredibly inspirational. We shared this with legendary New Zealand punk band The Warners. Drummer Mackie [Mike MacDonald]’s dad and his uncle had a printing factory in Onehunga. “Out the back, the MacDonald brothers used to watch Super 8 movies on an old projector. They had red-velvet draped curtains and that was our practice space, complete with old chairs and armless white statuettes. We’d go in there two or three times a week and practice.

‘Red Velvet Sofa’ was No.1 on Max TV for four weeks straight in 1995.

“To me it was a bit like Poles Apart, a dark, intimate folk club, also just a bit mysterious. ‘Red Velvet Sofa’ was about that emotional feeling of that dark warm space, so glamorous and curious.” The song sprung a video which was No.1 on Max TV for four weeks straight in 1995 and which also played on Air New Zealand’s in-flight programme for a few months.

Despite line-up changes (bassist Sean Reid leaving in late 1993, replaced by Christine Wells), success at 95bFM and disappointments (turned down as openers for the Cranberries as “too similar” but getting the RatCat gig at the Powerstation which they laugh about loudly), Crash remained a viable, busy and enthusiastic touring band, even though they always held down day jobs.

“We always worked, that was our thing,” says Natasha. “My day job was as a salesperson for a shipping company. I’m still in freight and logistics to this day, contracting now.”

Carden was a salesperson in the emerging home computer market.

“That way we could pay for the PA and a sound engineer for the night,” says Natasha, “and we could choose when we would gig. But the issue was that there weren’t that many venues in the early 90s where we could play”.

They played the standard circuit of Auckland live night spots, including POD, Squid, Arcadia, Pelican and “bars where there were screens playing sport”.

“It was the same people at the same gigs, touring in summer with the usual suspects,” says Carden.

Then the oddities: the Leather and Lace event, the tattoo convention (“the guy who ran the tattoo parlour on College Hill really, really liked us and we ended up playing there,” says Natasha, “and they were a very polite audience”) and big festivals.

Some stand out more than others, like the final night at the Gluepot in 1994. “As far as politeness goes,” says Carden, “that last show at the Gluepot in the downstairs bar! I’d never been into the Vista Bar before we played there that night. It was unofficially the King Cobras’ bar of choice, and they were into it [the gig], then at the end while we were doing our final song of the set, they picked up the pool table and threw it through the window. The whole bar got destroyed, the police came, and we got shunted out and couldn’t get our own gear.

“But the KCs carried out our gear and put it in the van. They even put my guitar in its case!”

Crash played at the SWEETWATERS 99 debacle – and got paid.

Crash played at the debacle of Sweetwaters 99 and got paid: “My one regret is” says Carden, “we played our set and I got completely wasted. Apparently, Grant Lee Buffalo played, and I love them, but I didn’t see anything”.

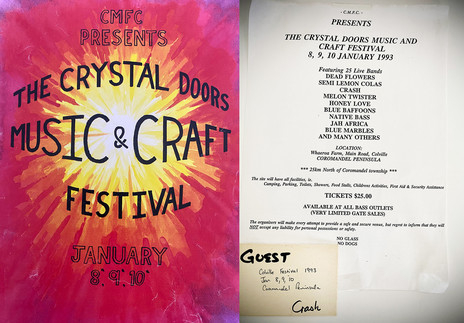

They played the Crystal Doors Festival at Colville where the promoter was so stoned they got paid twice; also Mountain Rock, where everything was so delayed, they went on at about 4am and Carden just started with a massive power chord …

Carden: “My favourite gig was the Furlong Hotel in Hawera with Stanley Manthyng and The Love Gang. Stan performed in hot pants playing reggae. Everyone loves reggae, right?

“But they didn’t like gay people so much in the 90s and I remember standing by the doorway and someone coming out and saying, ‘I didn’t pay $5 to see a bunch of faggots on stage’. And I was like, ‘No dude, actually you did.’”

Natasha: “Stan was just going for it saying, ‘come on you guys, don’t be such bogans! Come down the front and dance’ and the punters in their Swanndris just pushed their backs even harder into the back wall”.

“It was funny, but maybe not that funny because Sean did get a pint glass hurled through his truck window. But that was Hawera back then.”

Towards the end of the 90s they were playing less, and times were changing. Where one writer had dismissed ‘Red Velvet Sofa’ as being “very English, very boring” now Britpop was starting to become fashionable. Crash had got there a bit too soon, but a $30,000 injection from New Zealand On Air to record their debut album buoyed them.

Natasha and Carden reflect on a very creative time at the newly opened Revolver Studio in Royal Oak with Neil Baldock and a passing parade of people like keyboard genius Murray McNabb who would listen and sometimes sit in.

The late McNabb appears on the moody ballad ‘Song for a Boy’ written by Natasha about her cousin Josh who died in a car accident at only sixteen years of age. “I was about 22 when it happened, it fractured our family massively. We were all very close, us cousins back then, and my own brother was close in age to Josh. [‘Song for a Boy’] just needed to be done. His mum, my aunt, listened to it and loves it. It’s about who Josh was to me, to our family, an amazing guy.

“At that young age when something like that happens, it’s such a shock and I felt the only thing to we could do was write him a song.”

the moody ballad ‘Song for a Boy’ was given added magic by jazz pianist Murray McNabb.

Carden notes the song had a very Neil Young folk progression, but they took it in another direction with a mixture of programmed and live drums. Although the song was finished it didn’t have real magic until McNabb heard it and asked if he could play on it.

He says because producer Neil Baldock would have their songs up and playing, people were coming through the studio, hearing their work and admiring it. “I suspect Murray did that on more songs than we have credited him for, because the thing about Revolver was that there were so many instruments miked up the whole time, so there were many opportunities to add stuff.”

Carden also credits Graham Bollard (who wrote the original Shortland Street theme) for contributing his time and programming to some Crash tracks.

Their line-up changes – the album credits four bassists and three drummers – and guests presented a challenge for Failsafe’s Rob Mayes in putting the album together and wanting to credit everybody.

“Some of those credits are a little bit blurred,” admits Natasha.

Carden: “Those [other contributors] made for a very textural album.”

‘Grind Girl’ is a case in point and far removed from ‘Song for a Boy’: a massive song driven by a huge bass from Reid which allowed Carden to go the whole AC/DC.

Then there was ‘Geisha Girl’ which Natasha says was prompted by her fascination with beautiful Japanese geishas and the mystery that surrounds them.

“That was a classic example of what we’d do, “says Carden. “We’d have something, an idea, and that would prompt Natasha to think about something and she’d have a very visual storytelling idea.”

“Sometimes it is storytelling and sometimes it just comes out as emotion,” she says. “When I listen back now, I can hear common themes coming through which I was too close to hear before. There are lots of suns and moons and colours and feelings.”

With the album completed in what Carden calls a fruitful, supportive and creative environment – and what they believed was interest from David Rose at Warner Music to release it – Crash was ready to go to the next level after almost a decade together.

But things fell apart abruptly.

Today, Warner’s former CEO James Southgate (who signed The Feelers at that time and now manages Devilskin), says he wasn’t aware of Crash.

“I was the only person signing artists. I did not have anyone in A&R. It was possible David was talking to a band, but he never brought any band to me for signing. So Crash were not in the picture when I signed The Feelers.”

Labels in the 90s usually had only one rock band on their books and for Warners it would be The Feelers, although Southgate had his eye on Zed who he thought would be successful. But he still hadn’t broken The Feelers. “I had the attitude ‘100% on each project’ and if I couldn’t guarantee that I did not sign anyone.”

Zed found a home at Universal but, disappointed and deflated after years of slog, Crash were on the ropes again. Paul Ellis wanted their publishing for Sony Music, but they wanted to keep it; their drummer and bassist left for Britain; Natasha and Carden toyed with the idea of being a songwriting duo because every new rhythm section had offered them a new sound ... but life happened.

Natasha had a relationship break-up and her mother died suddenly, Carden just felt his music career had run its course. He got into downhill mountain bike racing: “I got sponsorship, so I travelled around and got big crowds, you feel like it’s a performance and no different from playing the Dogs Bollix,” he laughs.

“From the age of about 16 to 28 I’d been hanging out with musicians all the time. So suddenly I had friends who were refrigeration engineers but the thing we had in common, was bikes.

“When you’re in your 20s it’s all about being a rock star, whereas now it is only about the music.”

“I’ll still go to groups of people I know from the Five Bands for Five Bucks nights and half of them will have moved on and the others are still chasing the dream and talking about what guitar pedals they are using.” These days he’s highly successful tech entrepreneur who still plays piano regularly.

Natasha is married and still loves music of all kinds, and the Crash album recorded in 1999 – a bristling, strong collection of hard-edged guitar-driven rock – has brought back strong memories for them both.

Carden: “I’d been in two bands before Crash, just a guitarist who wanted to be Steve Vai or Yngwie Malmsteen. I lived with Bryan Bell [of Dead Flowers, now in the Jordan Luck Band] and he would just sit at home and play guitars all day because he wanted to be a guitarist as well. But at some point, we realised songwriting wasn’t impossible.”

Natasha: “Mike and I wrote together and came to the band with a handful of songs. Sean was more alternative, but he and I had a similar taste, so we had a crossover. And James and Mike had a crossover. There was this great collision of styles and personalities.”

Carden: “I love music but at the end I got to this point where I stopped enjoying it and got into this perspective of, ‘What song would be the most likely to get radio play?’ and so I stopped playing. But when I listen to this album now, I think, ‘What? I played that!"

Natasha: “It reminded me there was a lot of emotional care in it and that’s important to me. I was passionate about it at the time, and it was important, every recording or performance. I just wanted it all to be fabulous.”

“Initially for me the album was a memento, a ‘nice to have’. Now, thanks to Rob, it’s finally done, and people can hear it. We wrote stuff which connected with people and now we’re getting it out to them again.”

Carden: “I think one of my motivations for being in a band was just to hang out the back of the Powerstation and not be a punter. Then we started taking it seriously because before that we didn’t really think initially that it could be a thing.”

“When you’re in your 20s it’s all about being a rock star whereas now it is only about the music. When I listen to it, it’s not about us but more about the songs. So, for me there’s a more positive relationship to the music now.”

Natasha Reid - vocals

Mike Carden - guitar

Sean Reid - bass

Christine Wells - bass

Rick Fleming - bass

Kunio "Yoshi" Yoshida - bass

James Culham - drums

Matt Tait - drums

Willy Scott - drums

Visit our sister site

NZ On ScreenMade with funding from

NZ On Air