In 2003 Mark Everton interviewed Mike Chunn for the landmark television series Give It A Whirl. Below is an abridged excerpt from that interview, in which he discusses his adventures in Split Enz.

--

Pre Ends: Tim Finn and Mike Chunn (on piano) in their Sacred Heart College school band, the winners of the school's 1969 Walter Kirby Music Competition. Geoff Chunn is on bass, Paul Fitzgerald guitar, and Paddy O'Brien on drums. - Mike Chunn Collection

Tell me about meeting Brian [Tim] Finn.

The first time I met Tim [Finn] he was walking out of an interview with the Principal of Sacred Heart College and I was walking in. But I first remember him in terms of a musical sort of presence in early 4th form, that whole thing of me wanting to perform live. I just always wanted to get up in front of a bunch of people and show off, so being a musician, what a perfect way. He and I were sitting in a music room, it would have been something like ‘Yesterday’ – he just started singing, it was like, oh that’s good. He just had an innate sense of vocal delivery.

How hard did you want to win the Walter Kirby Award?

We worked very hard on it; it was a pity we weren’t allowed to use electric instruments. The double bass would come out, [we’d] blow all the dust off it and stick bits of Sellotape on. I don’t even know if we really knew what we were doing with this thing, but it didn’t stop us. For three years in a row, Tim, Geoffrey, and I with different mixes of other guys from the boarding school would put together a piece and work long and hard to get it perfect, and yeah, we won it in the 6th form year [1969]. I think we sang ‘To Love Somebody’ – the Bee Gees song. It felt good, a room full of people all listening and that whole competitive spirit that musicians have. It’s just one of those things, we wanted to beat the competition.

When you think about those very early days at Sacred Heart, do you think it planted the seeds for the subsequent effort and commitment that you put into Split Enz?

In essence [in boarding school] you’re incarcerated, it’s not like today where you can come and go as much as you like, so we built up a lot of dreams about what we were going to do once we got out of this place. Especially me and my brother Geoffrey, and Tim, we were all going to just get out there and do whatever we dreamed we wanted to do. For me it was always being on a stage playing a guitar. For Geoffrey the same thing, making a record, having a piece of vinyl with us playing on it was a huge focus for us. The minute we left boarding school we just pursued playing and rehearsing and we had a band called Stillwater, Tim, Geoffrey, me, Bob Gillies, a guy called Ben Miller. We were actually really bad; we were quite terrible. We would do Neil Young covers, Elton John covers, we didn’t really write songs or anything. It wasn’t until Tim met Phil Judd at the university that any kind of semblance of what became Split Enz – that seed was sown then. Our school years were really just us developing a need, the want and that dream to make us put in as much hard graft as we then had to do with the band.

Early Ends: Geoff Chunn, Mike Chunn, Phil Judd, Wally Wilkinson and Tim Finn, 1973/74. - Mike Chunn Collection

There was an awareness that you could take your music, that you were only just starting to formulate, and you could actually take it into the world?

Yeah, we sort of jumped through to the early Enz days. Thinking back to the early rehearsals with Split Enz on the balcony at Kohimaramara, the kind of joy, the sense of joy I had, of discovery and of finally some huge key turning in some lock that I thought could never be turned, was just unbelievable. We would laugh, we were so happy with what was happening, it was a great place to be. You would look out over the Waitematā Harbour – I just thought, that’s where we’re going, we’re just gonna float off and these songs like ‘Lovey Dovey’, ‘Stranger Than Fiction’, ‘Time For a Change’, ‘Wise Men’, ‘Split Enz’, ‘For You’ – they are hugely beautiful classy songs for a bunch of boys aged 20 to come up with. I just thought we ought to take all those elements that we have as well as these songs, especially stage performance and uniqueness. We’re not gonna have tight T-shirts and flared jeans like the rest of them, so we cut our hair, shaved off our beards. I wore my father’s pants and his doctor’s shoes. I used to enjoy wearing a thin tie you know, just going against the grain. Everything had to be against the grain but balanced with the belief that the music we were playing was totally extraordinary.

Split Ends 1973 - L to R: Wally Wilkinson, Mike Chunn, Phil Judd, Geoff Chunn, Brian Finn - Murray Cammick Collection

Where did that music come from, that early stuff? We talked about some of the influences, but it must have been some of the guys’ personalities.

The people I’d been playing with until university – we kept playing once we arrived there and we weren’t any better, you know. I knew that we weren’t a good band, Stillwater or whatever we called ourselves, but the minute Phil Judd arrived everything completely turned. Phil Judd, he’s from another planet really, he is somebody who can pick up a guitar and think “mmm I don’t know what this is, I don’t really know how to use it so I will just work out a way to use it”. He was lucky to have Tim with him to mould songs into melodies and structures. But the contrast between when Split Enz formed and we started playing and rehearsing – it was the difference between black and white. So Split Enz – really the whole thing started when Phil Judd came to Auckland and met Tim Finn and all our lives changed.

Phil Judd in the van, 1973. - Mike Chunn Collection

Can you tell us a little bit more about that songwriting partnership?

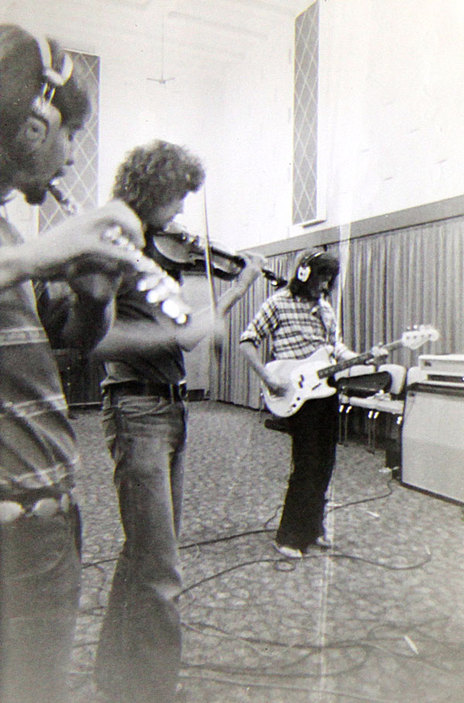

Yeah, I think they were totally complementary writers, with Phil’s supernatural kind of delivery of melodies. But more so, I’m talking about chordal structures I guess, which are often melodic in the sound. Some of them I can remember and play, in weird tunings. The song is kind of contained inside the notes of the picking that Phil would do, but Tim would then draw that out. Most of the words were Phil’s words and Tim would just give them a melodic life, bring his love of the three-minute pop song into the stuff that they were doing. So initially yeah, all this stuff that we did was brilliant when it was with violin and flute, me on bass and the two of them on acoustic guitar, it was like a sort of trippy folk quintet. Three-minute pop songs, that’s what they were. It wasn’t until we brought in keyboard stuff and just kept going on a tangent of making them more complicated and grandiose, that we ended up with the big long songs – but it started on a three-minute pop song basis.

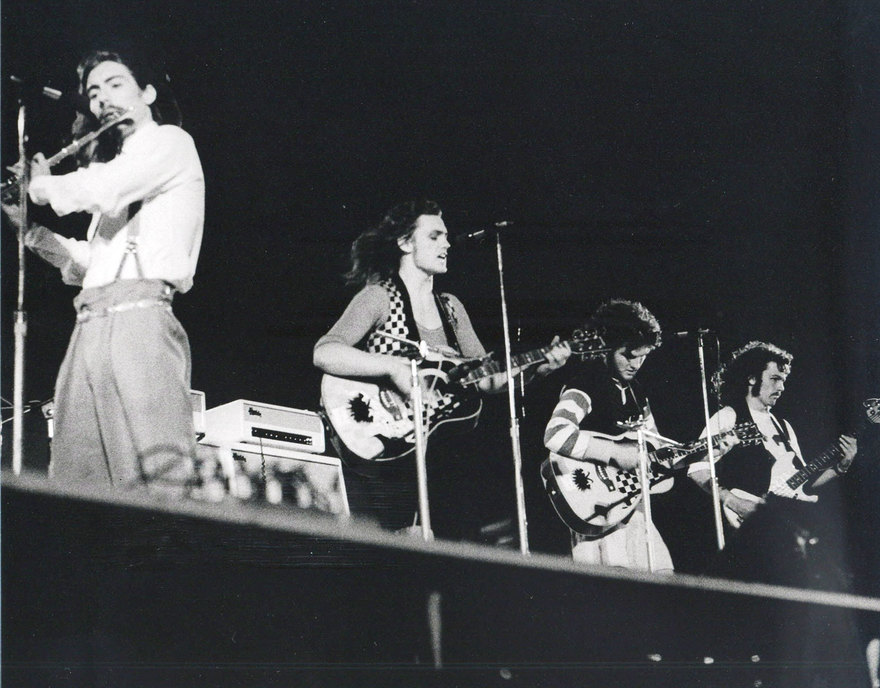

Split Ends at Ngāruawāhia, January 1973 - Mike Howard, Phil Judd, Brian Tim Finn, Jonathan Michael Chunn - Photo by Larry Jordan

What was the reaction to your early gigs – I’m thinking specifically of the Great Ngāruawāhia Music Festival – what was that experience like for you?

We were inexperienced on stage and at the Ngāruawāhia Festival, we were all shaking with fear. Tim had an Irish accent he was so nervous, and we all played twice as fast as we should have. Miles on the violin was shedding horsehair or whatever it is off his bow, it was a real lesson on how we are not ready to take on a big stage. But of course, we wanted to do everything at once so yeah, we took the big stage. We then went off and did smaller intimate venues but always concerts. We never went to hotels, we totally refused to play licensed venues where people might drink and turn around and talk to each other. We always wanted to have the entire room focused on what we were doing because we felt we’d put so much effort into it and we had something to say. We had music that we believed in so much, people should spend the time listening to it.

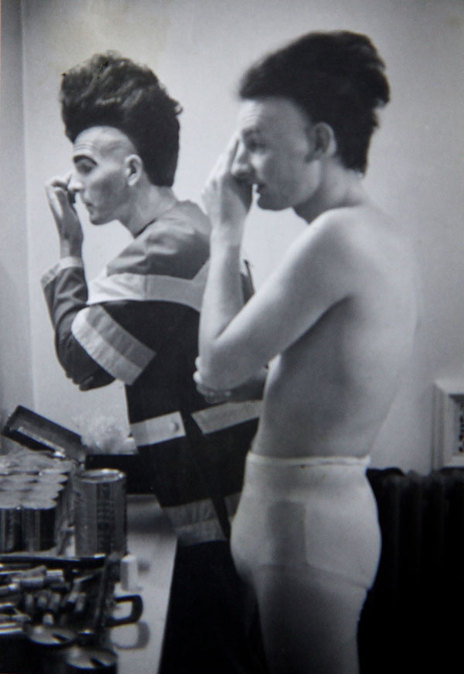

Tim Finn and Noel Crombie pre-show, 1976/77. - Mike Chunn Collection

Talk about Noel and what he brought to the band at that stage.

Noel Crombie was just wonderful. My first image [of him] – pink and white checked suit, huge sort of dimensions to it, walking down Victoria Street carrying a silver lightning bolt big cardboard thing. Big red beard, red hair, he just had a massive presence, and the minute he came into the band he took us by surprise. I don’t think we knew he was going to be doing it, but we had a song called ‘The Woman Who Loves You’, which has a piano solo, and we were playing away somewhere. All of a sudden he just appeared, stood there looking at us as if to say this is something you’re gonna have to get used to boys, pulled off his white gloves, put them in his coat pocket, pulled out two spoons and just shook them “tatooka tatooka tatunk”. Everything he did was so stylish and so brilliant.

Noel Crombie, Wally Wilkinson, Paul Crowther and Phil Judd, 1975/76. - Mike Chunn Collection

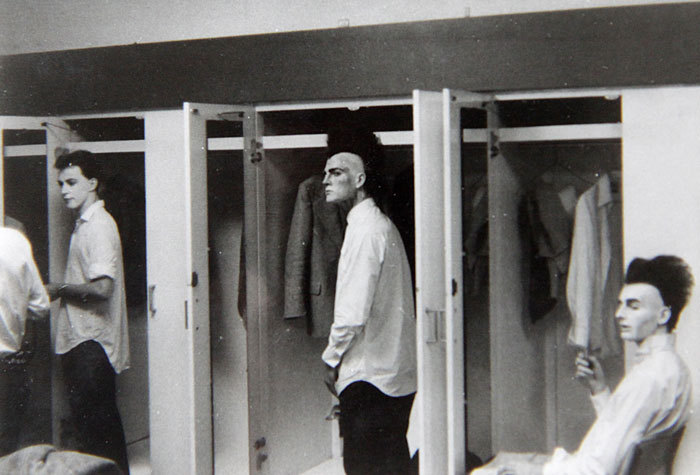

Can you remember the first time he brought costumes for you guys to wear?

We were playing support in Hamilton to Space Waltz who had the big hit ‘Out On The Street’. We were in the changing room out the back of Founders Theatre, and Noel walked in with a great bunch of coloured suits, zoot suits they were called. All fell about laughing, joyously embracing his craftwork. I had a beautiful yellow one with one sleeve short and one sleeve long, one leg short and one leg long, everything was kind of skew whiff, the whole strange dimensions you know, I guess a mirror image of what goes on in Noel’s head of design. We ran out on the stage, we felt a million dollars wearing those suits – they made us different again and we just loved being different. I think we blew Space Waltz off the stage, that was part of it too. Everyone we played before we had to blow off the stage and then the suits kept coming. There were different clown suits and medievals and all sorts, it was just wonderful.

Eddie Rayner, Tim Finn and Noel Crombie, Europe 1976/77. - Mike Chunn Collection

Tell us about putting on makeup and your suits. What did that contribute to keeping the band focused when heading onto the stage, what sort of feeling did that achieve?

The whole sense that we had that we were successfully creating our own unique identity. It made you feel – well I guess being in a band is a bit like it anyway – but married to these guys, an extreme emotional connection. But being typical New Zealand middle-class white boys that have had a lot of years in weird schools etc, we never had communication. We weren’t a band that talked to each other about any problems. It’s no secret now that I had a phobic disorder through all those years, never did I ever tell anybody about it. And if any of us had a problem with another one we just kept it to ourselves. Maybe in a way by just being staunch and carrying that belief about ourselves professionally, we were able to go through some pretty hard graft from New Zealand to Australia – start from the bottom, go to England and start from the bottom, into America and almost laughed at when we got there. What was the first review? “Who do these idiots think they are?” – and all that kinda stuff, but we persevered. Sure, I jumped out the end after about four years but that whole tight-knit sense that we were unique was really mirrored in the way we would get together backstage and just put our – it’s like masks, we all put our masks on. I would wear my Fisher & Paykel safety glasses, my father’s shoes ... I loved wearing my father’s shoes, cos no one else would ever wear shoes like that, they looked so dorky.

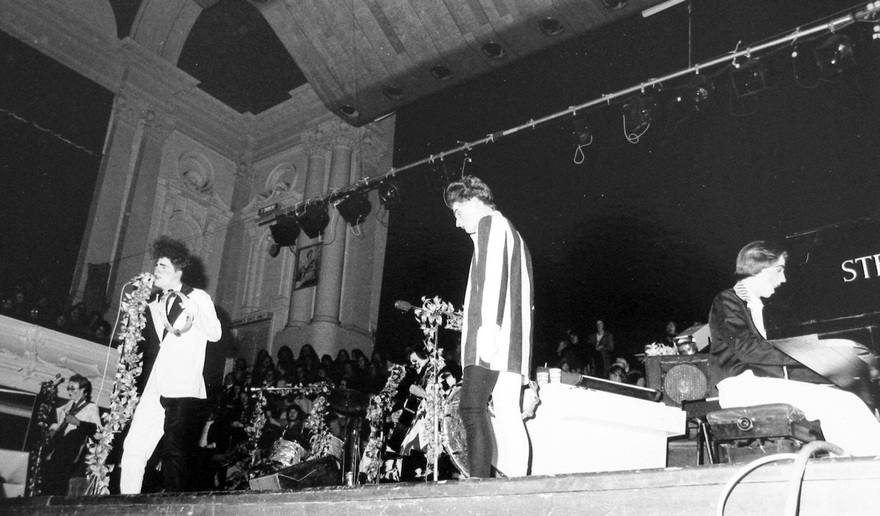

Split Ends at The Christmas Pandemonium Concert, His Majesty's Auckland, December 1974. - Mike Chunn Collection

Buck-a-Heads: what did they do to the bands?

The good thing about the Buck-a-Head concerts at His Majesty’s [Theatre, Auckland], it gave us an environment where we felt we could put on a show. Each of us had little areas of responsibility, Noel had the whole costume thing and being a character; Tim working on the whole front line of the stage. I would do all the audio effects. I loved putting together my cassette of sound effects for the Split Enz buck-a-heads. Every show would have a whole bunch of new songs, it was a glorious year, 1974. That kind of launched us through into going to Australia.

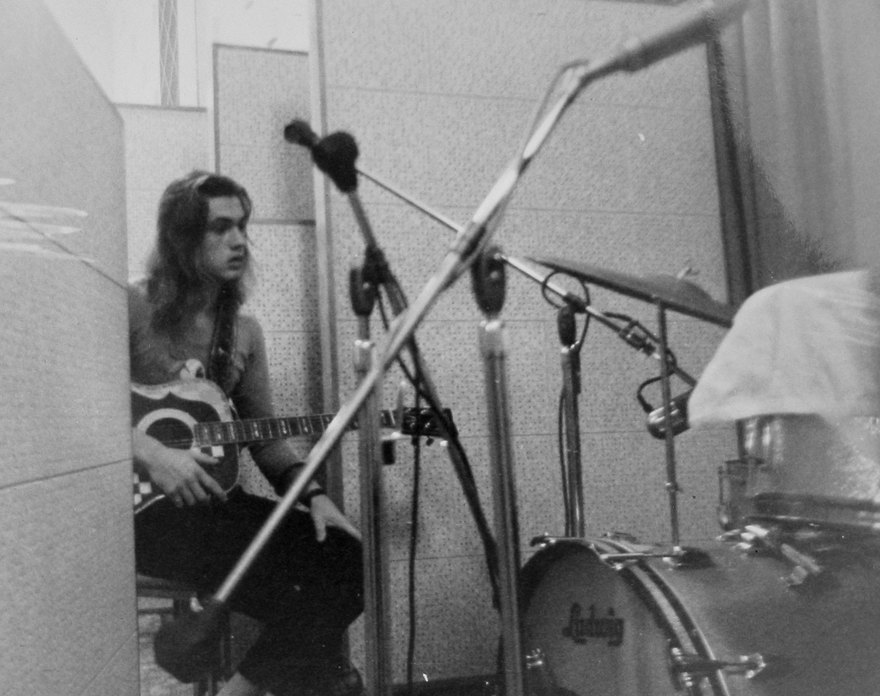

Tim Finn recording at Stebbing Recording Studios, Auckland, 1973 - Photo by Greg Peacocke

Mike Howard, Miles Golding and Mike Chunn at Auckland's Stebbing Studios, February 1973

Why did you guys go on the TV show New Faces?

Going on New Faces was our manager Barry Coburn’s idea. He had a direct line to the guy that made the show, so we were accepted for the heats without ever being seen or anything. It was who you know, not what you know, but we saw it as a chance to be seen by the nation on television and everyone would flock to us and want to come and see the shows. We just loved the idea of being able to make a record as well, we thought we’d record a song, put it into New Faces and release a single. So we recorded ‘129’, went into the studio did all that stuff that we always wanted to do, string sections and sound effects and buried it all inside this three-minute pop song, ‘129’. I think we won the heat or something, loved going down to Wellington and singing and doing a clip, and released the single ... it was never heard of again. Tim and Phil wrote another song for the final, ‘Sweet Talkin’ Spoon Song’, we loved going back into Stebbing recording studios and recording again. The recording side of it was fantastic, we did the finals and got second to last. We released that song as a single and ... that was the end of that one. Our attitude was pretty much “oh just they don’t get it” and so that’s when we went into 1974 and concentrated on the Buck-a-Head concerts. We didn’t release any records in 74, we just didn’t believe that our stuff would be accepted by radio stations if they hadn’t wanted to go with ‘129’ and ‘Sweet Talkin’ Spoon Song’. But the good thing about being in the finals of New Faces was we got to record four more songs because we got our own TV show like all the rest of the finalists called Six of the Best, so we went back into Stebbings and did ‘No Bother To Me’, ‘Spellbound’, ‘Malmsbury Villa’, and one other one, which gave us more recording experience. That’s when Phil Judd left the band because he just wanted to do recording. Recording through 1973 for the New Faces was a great experience even if the end result led us to nothing.

What sort of problems did Phil have on stage that contributed to him leaving the band?

Phil Judd didn’t enjoy playing live, I think he found it stressful. Initially it was a new kind of exciting thing, but once it became a bit of a grind ... Once it came down to the hard graft of touring and all, that he just didn’t want to do it. He’s just not the kind of guy that is naturally comfortable on stage, he’s uncomfortable in social environments. If you’re not a social kind of person, being up on stage is not a comfortable place to be.

Phil Judd recording with Split Ends, Stebbing Studios, Auckland, February 1973. - Mike Chunn Collection

Just before we leave New Zealand what did you think about New Zealand society? The smallness, the lack of expectation, whatever it is ... what is it about New Zealand that allowed Split Enz to develop the way that it did?

When Split Enz came through in the early 70s we were lucky in that the music industry really didn’t exist. We didn’t have to come up against a star-making machinery thing, a wheel of managers, agents, publicists, people in power. A country like England, at the time there was probably a layer of men in their 40s and 50s, 60s who if they said, “yes you will get the chance, up you come”, it would happen. Here in New Zealand, we just did what we wanted to do. There was no one to get in the way of going down to Wellington and putting on a show in the Concert Chamber, the reviewers would come and there’d be a fantastic review in the paper the next day. The word got out and it was a very kind of “if it feels good let’s just do it” kind of place. We did feel though that society in general thought we were wacky and zany. In a way we quite liked people reacting against us because we reacted against them, it was a nice symbiotic relationship.

Split Enz live at the Auckland Town Hall, 1976.

And you would have had a small and hopefully growing number of people who were totally into it?

We had fans who were absolutely dedicated, they bought right into the whole thing, loved the music, just the whole arrangement thing that we had. We spent a lot of time working on songs where we believed the arrangements were superlative, and the attitude we had mirrored theirs. I’m happy on a stage, I love being on a stage, it’s in me. I would always watch the audience and there were times when I saw them just ecstatic, everyone just staring and staring. It wasn’t like playing in a pub where you’re just the background. We believed that we were achieving this huge focus and while we didn’t play to thousands – well we did in the end play to thousands, we played the [Auckland] Town Hall two nights in a row. I remember when I was in fourth form I wrote a little essay, ‘My Favourite Dream’ or something it was called – I was in a band playing at the Auckland Town Hall and it was full, and I had an amplifier so high that I had to climb up a ladder to turn the volume up. Well, it all came true except my amplifier was much smaller, but we got there in the end. We achieved the dream and then the hard graft started because we also wanted to take it to the world.

Was there a sense of inevitability that you went to Australia? Why did you go there and what did you find initially?

Going to Australia was kind of the wrong direction. We’d always talked about going to England, and Australia was only going to be for three weeks because we were swapping with a band called Hush, who came here. Barry Coburn our manager put them on a tour and we were going to go into the Hush infrastructure, which didn’t know we were coming, it would appear. So we got there and it took us about two weeks to even find a gig, but we were lucky in that because we’d been announced as New Zealand’s Skyhooks – presumably because we put on some makeup before the show – they were curious to see us. We played a gig at the Coogee Bay Hotel, and Skyhooks came along and took a big shine to Split Enz, and went back to their record company saying, “you’ve got to see this”. Mike Gudinski turned up and it just all happened straight away. We were there four or five weeks and got offered a record deal with Mushroom Records. Gudinski is great, he has a whole infrastructure, so he had an agency in Melbourne, an agency in Sydney. We suddenly got shows every night of every week basically, driving up and down. I used to travel in the truck, I would hop into a single bed in the back of the truck cab, me, Murray the sound guy and Phil Judd would all be in the single bed together. Because of my phobic disorder it was perfect, I’d be taking sleeping pills, sleep for 14 hours all the way to Melbourne, and a week later drive all the way back up again. There was a lot of to-ing and fro-ing, we did 20 thousand kilometres in something like four months. In Australia we couldn’t do it the way we’d done it in New Zealand, we couldn’t just do concerts, we would have been laughed out you know, so we had to go to the hotels and the pubs, do the hard graft. I think we made an impact because by the end of the year, six months later, or whatever, we were selling out halls like the Dallas Brookes Hall in Melbourne which holds 1500 people, so we’d built up that audience.

What did Gudinski tell you initially? Why did he like the band, why did he sign you?

I think Gudinski signed Split Enz because Skyhooks told him he should. At that stage we were looking pretty wayward in terms of presence, the three-minute pop songs had gone we were doing up to 15-minute pieces. He took advice from those around him and made a decision, also he was a bit flush at the time because Sky Hooks had sold a quarter of a million albums, so he thought well you know, I can invest in this. To his credit he hung in with that band until five years later it finally paid off.

Split Enz - Mental Notes (White Cloud, 1975)

Tell us about recording Mental Notes – to finally getting some of these other songs down?

Mental Notes ... I enjoyed the process. I mean I was grappling with this phobic thing but in the studio, it was a beautiful little isolated world. Maybe I did enjoy boarding school after all, and so here was another kind of place where we just created our own universe. There were tensions. Tim had built up this moment for so long. It was only three years but ... the path we were following just had so much in it, it was like a decade of “this album has to be the one”. He was tense in the studio, so much so that the next album, I think he was banned from being in the studio when we didn’t need him. Having Dave Russell (Ray Columbus and the Invaders) as a producer was good in terms of our having a rapport with someone in the control room. The engineer didn’t like us, it was a real pity we didn’t have an engineer that loved what we were doing and would have put a lot more creative skills in. Aspects of the album we were disappointed with, but it seems to have legs and lasted a few decades. I still get my royalties, there you go.

We believed ‘Maybe’ had a chance of being a hit single, but it wasn’t to be. Listening to it now, we could have done things a bit different that made it more instantaneous. It was a great little song, it had been around for a while – it was something Tim wrote way back in 71 or 72, which is highly relevant really.

Eventually you did get to the UK.

Well Gudinski having interest from film – and knowing that the whole rock scene music connection with film – meant a lot of doors were open in the UK. He invested in sending us to the UK to record Second Thoughts, whether it was a good idea or not to re-record songs off Mental Notes in terms of what was happening in Australasia. Possibly it wasn’t a good idea, we came up with an album that didn’t really kick in Australia and New Zealand because people said, “oh I’ve already got half of those songs and some of the new stuff”. Some of the stuff prior to Mental Notes probably should have been considered to create an album of new recordings of songs that people hadn’t heard before. The list of songs that we learnt prior to going to Australia that were never recorded is something like 16, all sorts of songs, a lot of them three-minute pop songs. England found us very vibed up about being there, we finally got where we always wanted to go – 1976 wasn’t a good year to go, we probably should have gone in 1973 when the Sex Pistols, The Clash and the Damned weren’t about to release their records, but there you go, got to see Buckingham Palace.

Publicity shot used for Mental Notes artwork. From left: Wally Wilkinson (back), Timothy Finn (front), Noel Crombie, Eddie Rayner (back), Jonathan Michael Chunn (front), Philip Judd, Emlyn Crowther (as they were called on the album) - Simon Grigg Collection

Tim and Noel were very aware of what was happening in the industry. There was a feeling that something new was going on but it wasn’t really until we saw this huge Melody Maker spread on punk rock written by Caroline Coon that we suddenly thought “uh-oh”. Alarm bells rang, we’d just finished recording the album. We had a year then of basically trying to sell a record completely against the tide. By the time we got to the States it was just mildly if not at times overly depressing having to know that we had a record that was old-fashioned.

Was it really that much against the tide?

This is Second Thoughts. I started learning songs that ended up on Dizrythmia,but the agoraphobia was just so – it was like this mushroom cloud I was inside and you just couldn’t see past that day you were in. I remember learning ‘My Mistake’ and ‘Parrot Fashion Love’, but I had to go so I went back to New Zealand. When I heard Dizrythmia – “aah they got three-minute songs, an album full of them, and good on em”. It’s exactly what should have happened and if Phil hadn’t left, maybe it would have still gone on in that kind of convoluted way. The songs we were learning, that were being written post-Second Thoughts with Phil in the band, they weren’t working. We would learn the same song week after week, turn it round, grind it down, put it in the mixer, it would come out a bit different, but we just lost the thread really. Tim’s obsession with ensuring that a path was maintained drove him to write all those songs on Dizrythmia with Eddie’s help here and there, and it worked.

Punk did in a strange way give the band a bit of a kick up the arse.

Punk rock basically catapulted Enz back to the three-minute pop song, the intense live performance, because they were seeing what was going on around them. You know if you go and see The Clash live, that’s what you have to do. It’s no good saying “oh well this is how it works with Peter Gabriel in Genesis, you know it’s beautifully crafted in its time” – even the critics today that will laugh at British progressive rock, they were all listening to it at the time. It was huge, things change, and Enz changed beautifully with the times.

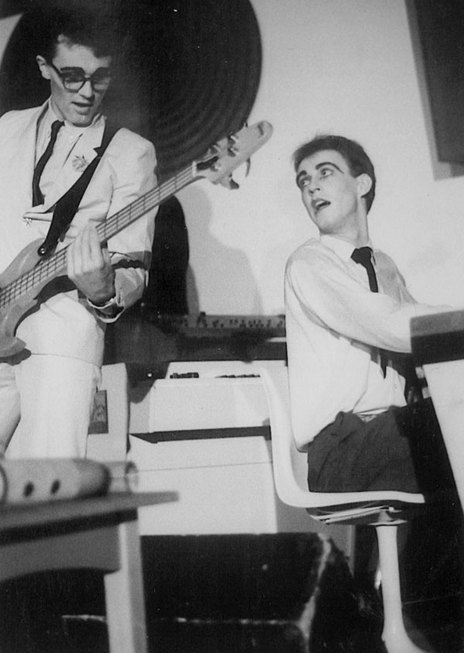

Mike Chunn and Eddie Rayner, 1976. - Mike Chunn Collection

What was Eddie Rayner’s contribution in those days?

Oh, Eddie was a total genius, and there were those that say you shouldn’t tell him that. I first saw Eddie with Orb, Paul Crowther on drums, Alastair Riddell out front. He was playing a Yes song, ‘Roundabout’, and I remember thinking wow that guy is good. The minute we decided that Tim would come off keyboards and go out front, this is nearly 74, he was the guy to ring. And he’d been at Sacred Heart, how could we not, we had to ring Eddie Rayner. He turned up in this room behind me here with the same piano that’s still sitting in it and we said “well if you sit down there we’ll show you what we’re doing” so we played a few songs and he was – I could see he was like, “this is good”. We sat him down and said “why don’t you just join in on one of them” which I think was ‘No Bother To Me’, and off he went and we thought “he’s good”. It was like love at first sight, some enchanted evening, and Eddie was in from that day. It was one of those things, he knew one day he’d be in, and we knew one day he’d be in, we just had to give him a call. His influence is enormous. If you listen to The Beginning of the Enz to the tracks that were done without him and then the tracks with him, there was a huge difference in terms of expertise and bringing the best out of cool structures.

Were there any positives to come out of Second Thoughts?

Second Thoughts – I thought was a great title. The costumes, the cover art, titles, Mental Notes, Second Thoughts, all great. Did anything good come out of the release of the album – not really, I don’t think so. Didn’t sell a lot, we felt that the production was quite clean and a bit nice compared to Mental Notes. I think Mental Notes is the one. We should have done new songs – ah well – Second Thoughts came and went, Bob’s your uncle, got me to America, what a shithole.

‘Late Last Night’ – Noel’s first video.

Split Enz and videos, ahead of its time really with Noel Crombie’s whole vision of how you present a song on a television. ‘Late Last Night’ was the first one where we got proper film and 16mm cameras out. I saw it as a chance to be an actor, so I pretended I was drunk and I got to smoke cigarettes and wear my glasses, play a character, cos I just liked playing characters. It made an impact back in New Zealand and in Australia. Not that the record sold, but we were used to records not selling by then, singles, so we just moved on.

When did you go to America and what did you find there, what did they think of you?

We went to America to promote what was called Mental Notes – it was Second Thoughts yeah, the second album – in February 77. It was a commitment we made because Chrysalis Records in America had said we’ll release it if they come. We thought United States, cool, so off we go into LA and up-and-down electric windows in a limousine, sticking our heads out the electric sunroof and turning the TV on in the limo and changing all the FM radios cos New Zealand [only] had AM, and all that kinda stuff. But after about a week in LA we suddenly realised that we were held up to be a bunch of zany nutty weirdos from a distant country and it was a gimmick thing. The promotional device of a clay model of Noel’s head into which you planted grass seeds, watered them, and he grew a funny haircut ... we went to a dinner with some radio people, by then of course we were even more antisocial than we’d ever been so we just – we didn’t do the hard graft socially. There were probably major radio people sitting round this big table in LA and there was Noel’s clay head in each place. The whole thing was really not about the music at all. In Atlanta they had a lookalike contest that no one entered, the prize was a trip to LA to see Jethro Tull, second prize was free hairdressing at this hairdressing salon ... the guy who won looked like me, in fact he looked more like me than I did.

A Split Enz dressup - Dallas, Tx, 1977. - Mike Chunn Collection

America, America – a big “U” shape, San Francisco, around the bottom, ended up in Chicago. My agoraphobia was paramount at this stage. It was beautiful, I was on tranquillisers, beautiful, dreamy ... I got to eat cherry pie, pecan pie for breakfast, grits, I had grits in Dallas, God they tasted terrible. I remember sitting in my hotel room in 1977 watching Taxi Driver on the TV going “oh Christ that’s what it’s like out there”, so I just stayed in my room the whole time. It was a surreal trip of three weeks, it felt like three decades. And I wouldn’t have missed it for the world, because at least I got through to the other side. It had nothing to do in the career of Split Enz, however.

So you went back to the UK, hard times?

For about a day, I didn’t last.

You didn’t last, you went.

Well, I came back here to ask Alastair Riddell to join the band, cos Juddsy had gone, but he said no after a while. I was here about three weeks and then I forced myself to go back to London, but just knew I had to go so I came back again.

Mike Chunn and Tim Finn reunited on stage, Sweetwaters 1983. - Mike Chunn Collection

You’ve been obviously a musician, a band manager, and you’ve been involved in the business side of the industry. What do you think of the attitude of musicians themselves?

Well, I think musicians are driven by their personalities. They are what they are, and bands are like a microcosm of society. Certain people are attracted to certain instruments that mirror that personality trait. I’m a bass player, I look at other bass players and yeah, there is a certain aspect to what we’re after that drives us to that instrument. Drummers are drummers, front people are front people. The mix of those with huge egos and selfish natures tends to find people going from band to band all the time. Being in a band is like being married to three or four other people – I believe it comes down to the craft of compromise. The best bands are those that understand the intense subtext of the relationships they have, if there is a problem there’s no point in just running off and leaving the band. Learn to get on. There are bands that have been around for decades that hate each other, but they’ve understood that if they go off on their separate ways, they’re kissing goodbye to something that’s pretty good. The beauty of New Zealand musicians in the main is that they all have great respect for each other; the competitive spirit might be there, but it doesn’t lead to obvious moments of public arrogance. No one spits the dummy on television ... oh mind you I saw someone throw an egg at Th’ Dudes at Sweetwaters. Yeah, musicians, I just think they’re a great, gregarious bunch of crazy people.