Farmyard

Wellington band Farmyard may have had a short career – just two albums in two years at the dawn of the 1970s – but their progressive folk-rock and sometimes penetrating lyrics on their self-titled debut captured the mood of that changing time.

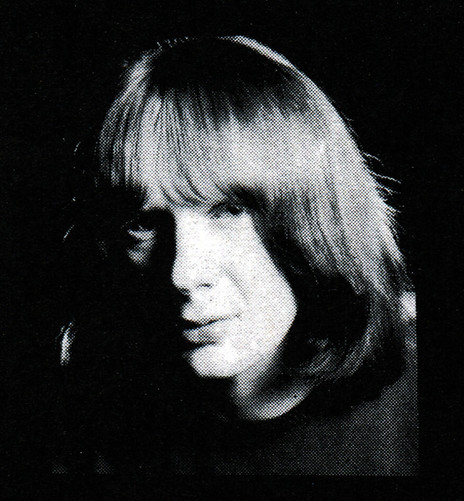

Farmyard's Paul Curtis (vocals, guitar)

Farmyard - Back to Fronting (Polydor 1971)

Farmyard: "New Zealand's First Supergroup"

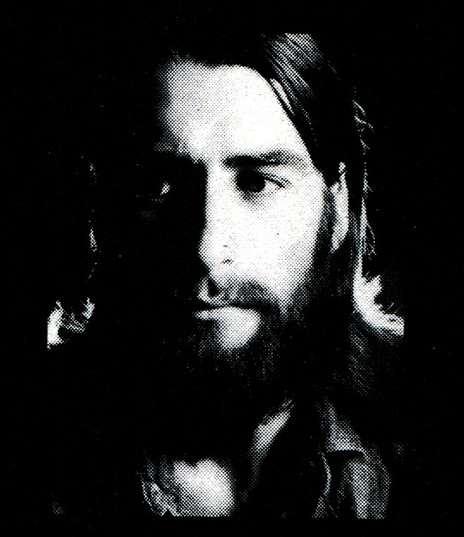

Farmyard guitarist Milton Parker. “A serious musician, Milton has passed Grade 8 on guitar and his ultimate ambition is to become a classical guitarist.” – Polydor flyer

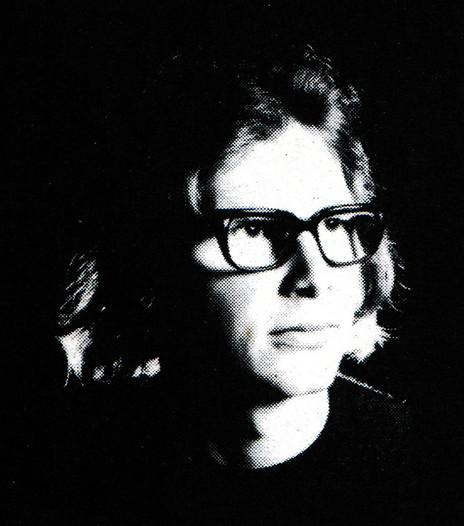

Farmyard's Andrew Stevens (flute, saxophone). From a Polydor flyer: “Eighteen year-old Andy has learnt the flute for eight years and has passed Grade 8 Royal Schools with distinction. “Last year he played piccolo with the National Youth Orchestra, as well as pursuing a keen interest in rock-oriented music.”

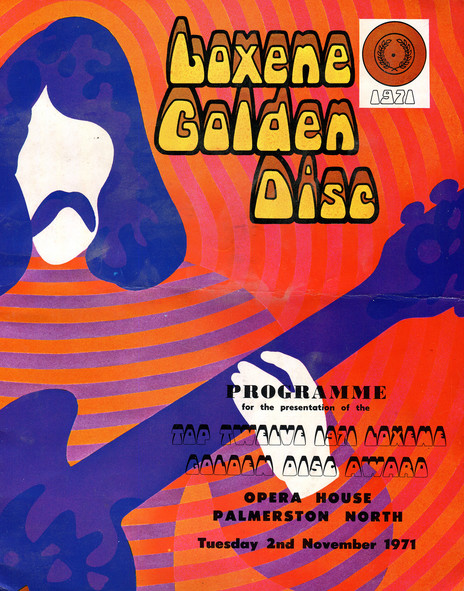

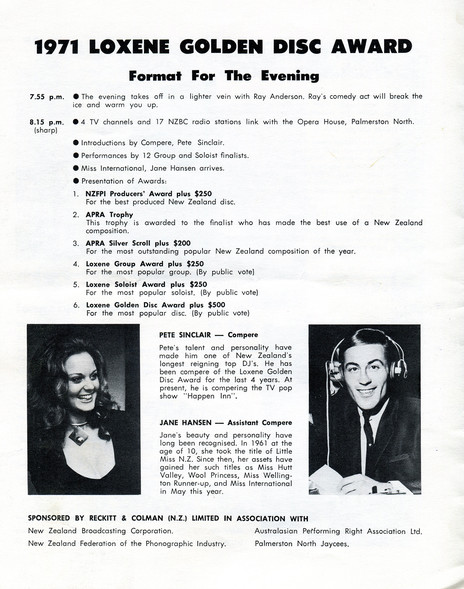

The cover of the programme for the 1971 Loxene Gold Disc, held at the Palmerston North Opera House on 2 November.

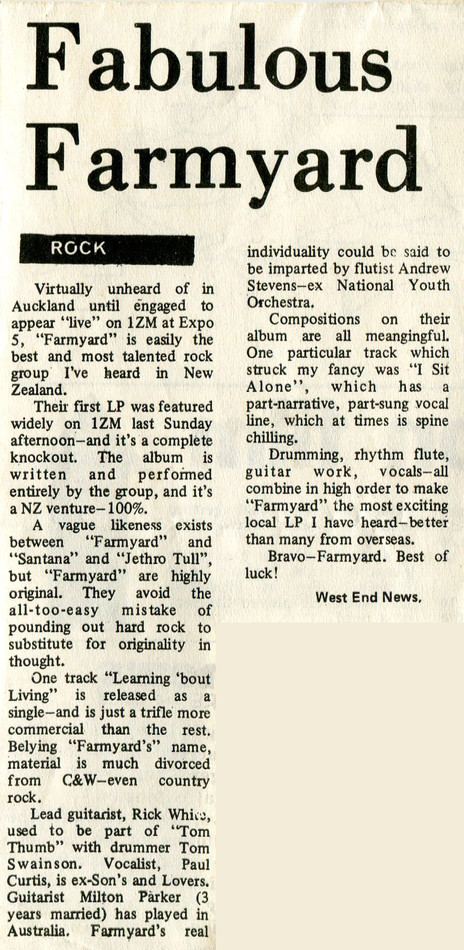

Farmyard review, from the West End News, Auckland.

Farmyard: bassist Rick White and Andrew Stevens (flute, piccolo, tenor sax), May 1971.

Photo credit:

Rick White Collection

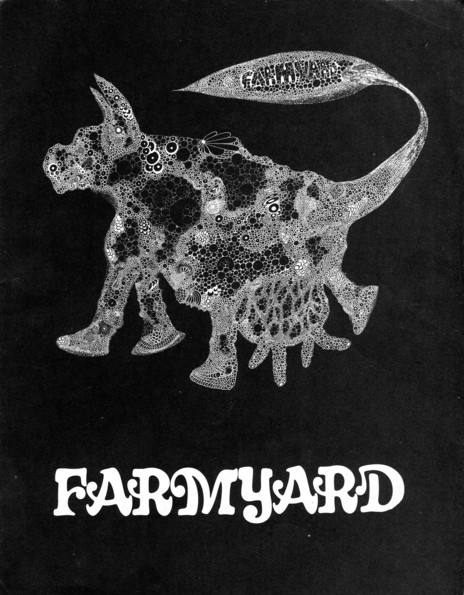

Farmyard: the cover to a promotional flyer at the time of their debut album, 1970.

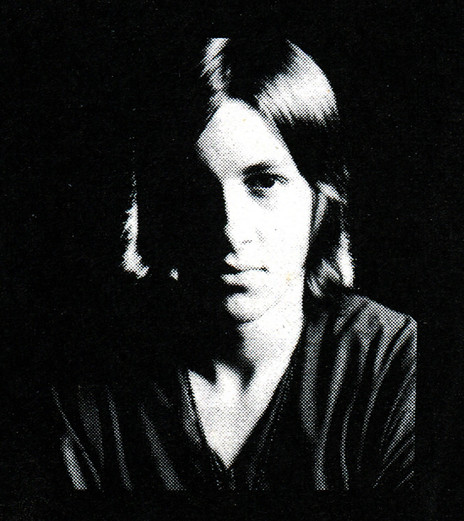

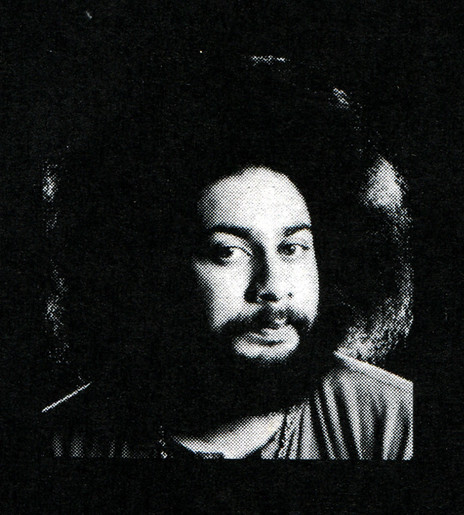

Farmyard vocalist/guitarist Paul Curtis. Originally from the UK, he was in Nomad and Sons & Lovers before Farmyard. A Polydor flyer says: “Has no formal musical training, plays guitar and sing – and you should hear him “sing”.

Photo credit:

Rick White Collection

Farmyard's self-titled debut album (Polydor 1970).

Farmyard - 'Which Way Confusion Part 1' produced by Peter Dawkins (Polydor 1971).

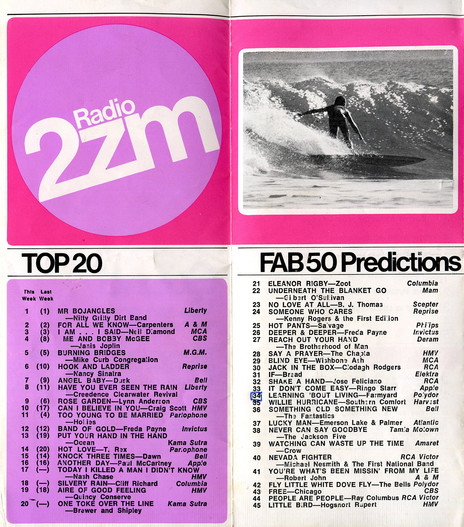

Ones to watch: Farmyard in 2ZM's Fab 50 predictions, 1970.

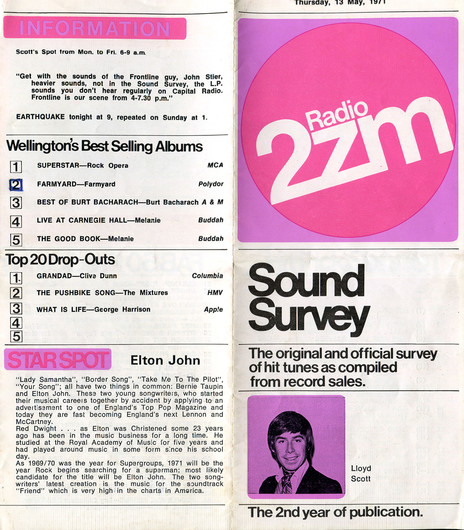

Farmyard's debut album is Wellington's No.2 best-selling album in radio station 2ZM's Sound Survey, 13 May 1971.

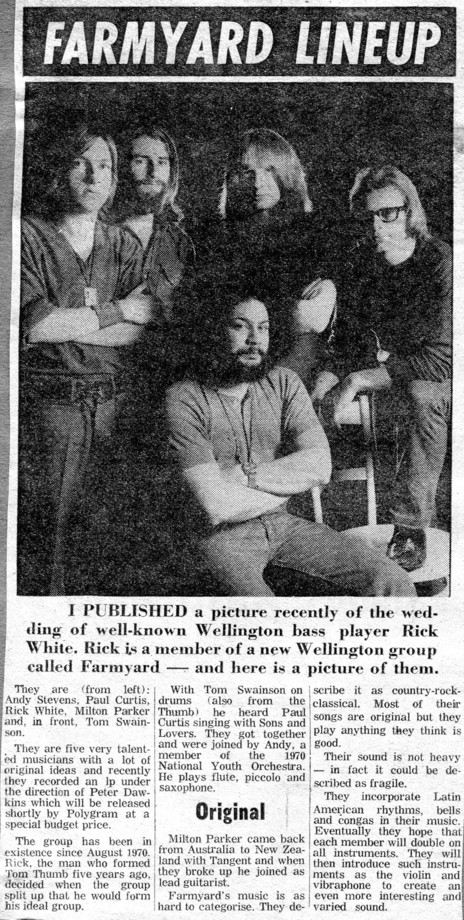

A music column announces the arrival of Farmyard: "Their sound is not heavy - in fact it could be described as fragile."

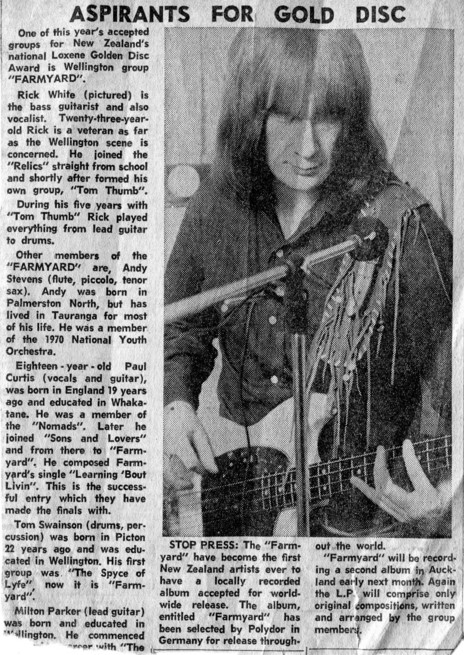

Farmyard's Rick White, in an Evening Post piece about the group being finalists in the Loxene Gold Disc, and their album being released internationally.

Farmyard: a "gay atmosphere" at the Dental Nurses' Jubilee Ball.

Rick White in Farmyard (bass, vocals). From a Polydor flyer: A 23 year-old veteran who has “played everything from lead guitar to drums. Now the auburn-haired wonder is Farmyard’s official bass guitarist – and he sings too!”

Photo credit:

Rick White Collection

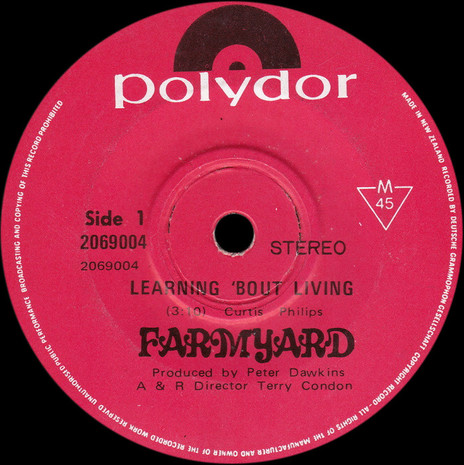

Watch: Farmyard - 'Learnin' 'Bout Living' - a pioneering music video often played on New Zealand's only TV channel in 1971.

Farmyard's Rick White (bass, vocals).

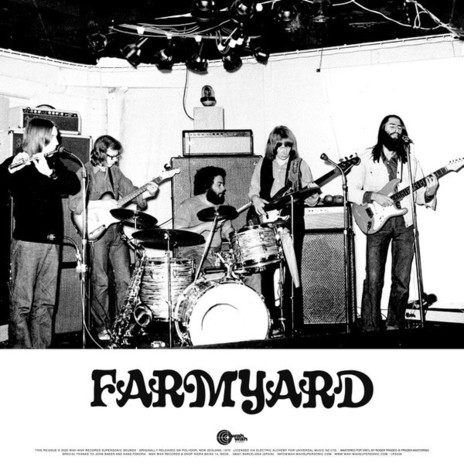

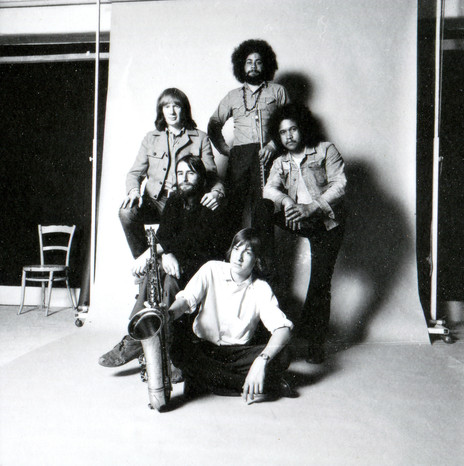

Farmyard, left to right: Rick White, Paul Curtis, Tom Swainson, Robbie Mackie; Andrew Stevens is sitting in front.

Photo credit:

Rick White Collection

Farmyard - Learning 'Bout Living (produced by Peter Dawkins, Polydor, 1970)

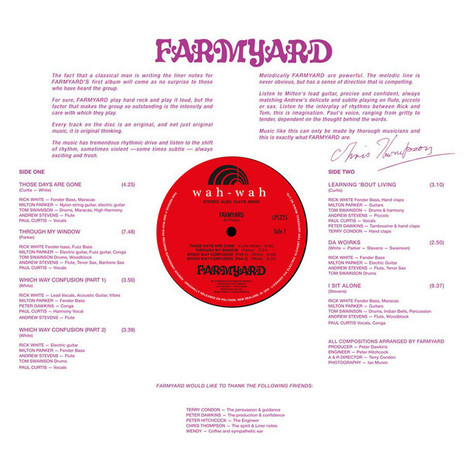

Farmyard's debut 1970 LP, reissued by Spanish label Wah-Wah Records in 2020.

The show rundown for the 1971 Loxene Gold Disc at the Palmerston North Opera House. The show was broadcast simultaeously on NZBC TV channels AKTV2, WNTV1 CHTV3, and DNTV4, as well as on 17 regional radio stations. The total prize pool was $1450.

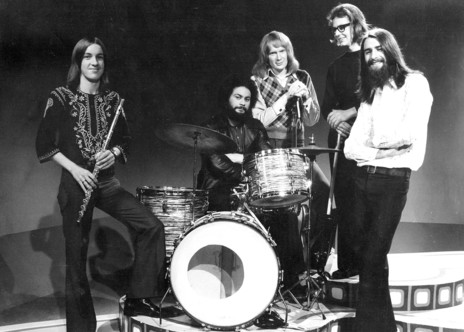

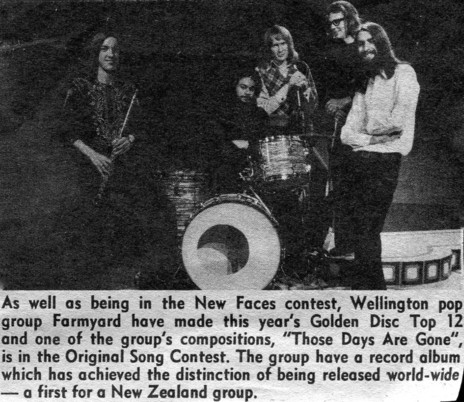

Farmyard in 1970, when they were on the New Faces TV show and finalists in the Loxene Golden Disc. Left to right: Andrew Stevens, Tom Swainson, Rick White, Milton Parker, Paul Curtis.

Photo credit:

Rick White Collection

Farmyard's second album described in a Polydor promotional flyer.

Farmyard, L to R: Andrew Stevens, Milton Parker, Tom Swainson, Rick White, Paul Curtis.

Photo credit:

Rick White Collection

Farmyard, from left to right: Andrew Stevens, Tom Swainson, Rick White, Milton Parker, Paul Curtis.

Photo credit:

Rick White Collection

Tom Swainson, drummer and percussionist, “is 22 and very hairy … A keen jazz fan, Tom sings and plays the drums. In between times, he eats.” – from the Polydor flyer inside Farmyard’s debut album, 1970.

Farmyard, clockwise from top left: Rick White, Tom Swainson, Robbie Mackie, Andrew Stevens (seated), Paul Curtis.

Photo credit:

Rick White Collection

Farmyard, pictured in the NZ Listener in 1970.

Farmyard, L to R: Andrew Stevens, Milton Parker, Tom Swainson, Rick White, Paul Curtis.

Farmyard's debut 1970 LP, reissued by Spanish label Wah-Wah Records in 2020.

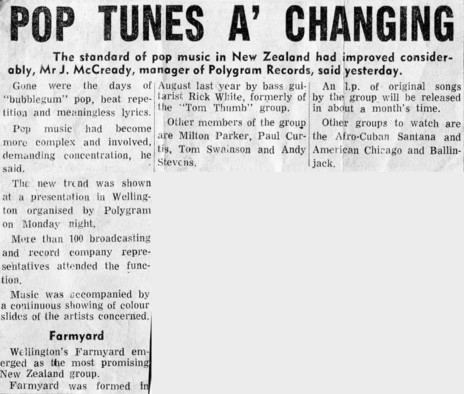

Farmyard - "most promising New Zealand group."

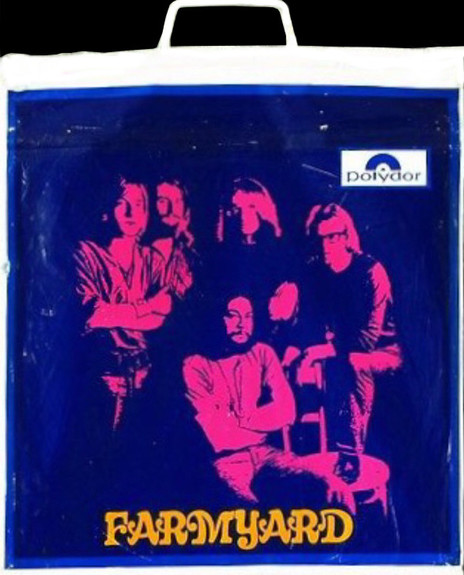

The self-titled Farmyard debut album came with a plastic bag cover and included a fold-out calendar. (Polydor 1970)

Labels:

Polydor

Discography

Members:

Rick White - vocals, bass

Tom Swainson - drums

Milton Parker - guitar

Andrew Stevens - flute, saxophone

Paul Curtis - vocals, guitar