Harry’s own wanderlust struck 20 years later, as a married man aged 26 with a young family. By then, the early 80s, he had a growing expertise in classical and acoustic guitar styles, and decided to bring his wife and two young children to Wellington. He has been living in New Zealand ever since.

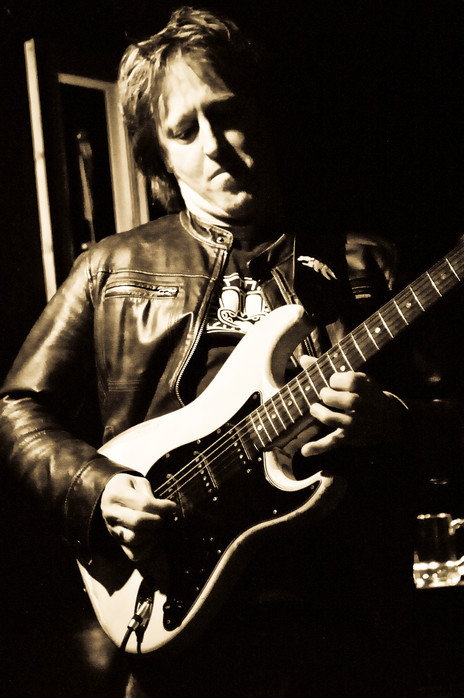

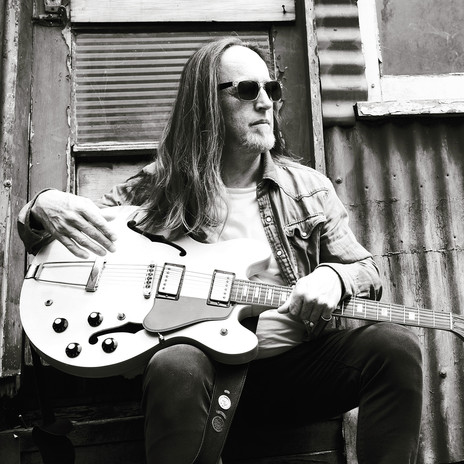

Harry has an honours degree in Media Arts from Wintec New Zealand and teaches music arts full time at the Jazz School of the Ara Institute of Canterbury (formerly CPIT, Christchurch Polytechnic Institute of Technology). He is a prominent composer and performer of large-scale avant-garde music in concert festivals, plays in various of his own and others’ jazz, rock and roots bands, and has played electric or classical guitar in each of the major New Zealand orchestras (Christchurch Symphony Orchestra, Wellington Sinfonia/Orchestra Wellington, Auckland Philharmonia Orchestra and New Zealand Symphony Orchestra), backing artists including Bic Runga, Renée Geyer, Whirimako Black, Julia Deans, Midge Marsden and Dave Dobbyn.

But none of that was formulated yet in the mind of the little boy who had come out on the Fairsky in 1967, one of the last ships through Suez Canal before the Arab-Israeli War that year.

Harry’s pathway into a life of music was via his grandmother, Mary Barr, who emigrated to Australia a few years after the family and lived the rest of her life with them in a sleepout his father built for her.

“My dad played a tiny bit of piano,” Harry says, “and we had one of those home organs with drum beats, but the real music came from my grandma. She played the banjo-mandolin and liked to sing. I was always asking, ‘Can I play it, please?’, so for my 14th birthday, she asked if I would like a guitar. That’s how it all started. When it was the Top 40 countdown, I’d grab the household transistor, take off to the bedroom, lie on the bed and listen to all the songs.”

He started finding his own way around the guitar through listening and copying, had a few lessons and played in a teenage band with some mates. When that band broke up, he got into finger-picking acoustic guitar, inspired by Leo Kottke. At 19 he took part-time theory lessons and began his three-year study of classical guitar at the Sydney Spanish Guitar Centre, eventually achieving grade eight. By his mid-20s he was supporting his young family through music – teaching and doing classical guitar recitals.

In his mid-20s, Harrison thought “let’s do something crazy” – and moved to New Zealand.

“We hadn’t long moved into a rental property and the landlord told us he was going to put it on the market. Rather than move again it was, ‘Oh, let’s do something crazy.’ I taught guitar for a living and felt that I hadn’t really done much adventure before having kids, so this was an adventure that the whole family could go on.”

At the beginning of their New Zealand adventure, the family stayed with a Kiwi friend they’d met in Sydney and then bought a house bus in Wellington, living in it off their savings for the next six months or so until cabin fever with two young children got the better of him. Harry applied for and was accepted onto a government-run PEP scheme, whereby artists could draw a limited income and hone their craft over short blocks of time.

“I had six months on that. There was a headquarters where all the artists had to come and have meetings once or twice a week. You had to go in and rehearse and they organised shows for you. It was really good.”

Questions about who he was and where he was from began to arise in relation to government schemes and regulations. Until then he had British citizenship and whatever rights were granted to Commonwealth citizens. He hadn’t applied for Australian citizenship, so instead opted for permanent residency in New Zealand. He put down roots and doors began to open for work.

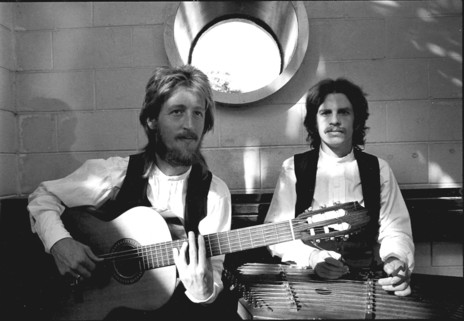

After his PEP course Harry paired up with American hammer dulcimer player, Michael Warmuth, writing music together and doing the acoustic club circuit, but his income was still slim. He applied to and was accepted for music teaching positions at both Christ’s College and St Andrew’s College in Christchurch, so he packed up the family once again and moved south.

“The teaching fed the family basically, and then out of the blue I met guitarist Mark Kahi. He wanted to leave the covers band he was in and asked me if I wanted to audition for it.”

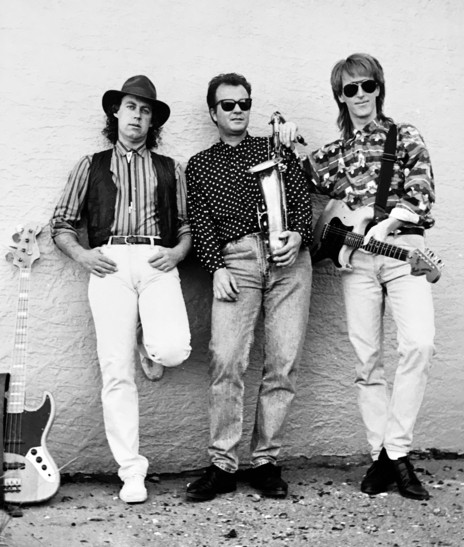

That band was Sneaky Feet. Danny Wilson was on sax and flute, Harry on guitar, Marc Beecroft, bass, Wayne Beecroft, drums – and both Marc and Wayne on vocals. The band was a going concern from 1985-89, with a high profile around the city and environs, its line-up expanding or contracting around Danny and Harry over the years or to suit the nature of the gig.

“Danny and I had a duo, Ozone Brothers, from 1990-94 and I rejoined Sneaky Feet after that with Danny, Rob Carpenter on bass and vocals, and Wayne Allen on drums and vocals,” he says.

“Danny was the link to getting into playing commercially, making regular money for people and playing what people wanted. But I always had the passion and appetite for my own music and listening to other sorts of music that weren’t very popular. That always was simmering away in the background, and it just got to a point where that took off.”

“I always had the passion for my own music, and listening to other sorts of music that weren’t very popular.”

The arc of his musical knowledge base was set on an upward curve when guitarist and gypsy jazz specialist Keith Petch asked him if he would like to join him, dynamic violinist Fiona Pears, and bassist Mike Kime in the Blue Swing Quartet. The band specialised in Hot Club de France stylings – fast and swinging Euro jazz à la guitarist Django Reinhardt and violinist Stéphane Grappelli. Until this point Harry had little jazz in his kit, so the quartet was a swift, on-the-job learning experience in the heated Hot Club-style musical atmosphere.

“Keith had loads of experience, in that he was sort of the leader of the band, so I learnt a lot from him and playing it. It really had some energy. That was my link into jazz and after that band finished, I started playing with other jazz musicians, playing standards. It helped me realise where I was heading and that the kind of music I like to write was more along a certain style of modern jazz rather than rock or pop.”

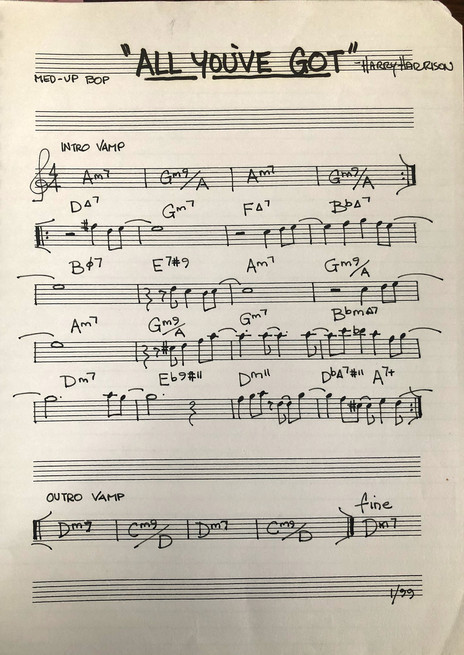

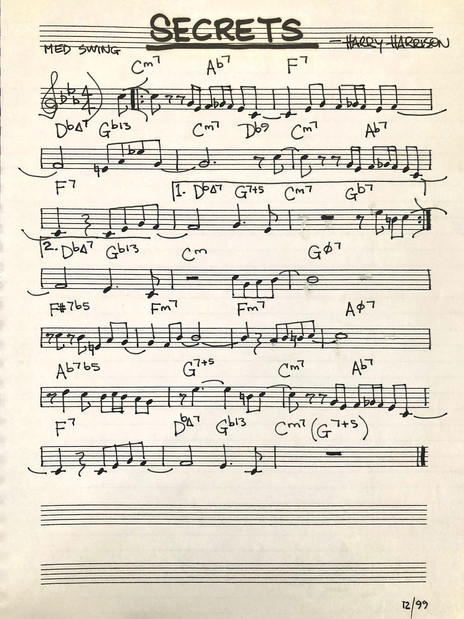

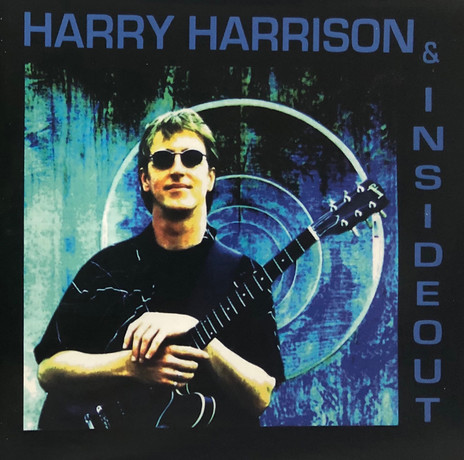

Around that time he formed Inside Out, a contemporary jazz band playing his own and others’ compositions. It was all instrumental music and the line-up comprised, variously, saxophonists Gwyn Reynolds and Simon Lean-Massey; Cameron Pearce, trumpet; Darren Pickering, Tom Rainey or Ben Gerrard, piano; Mike Kime or Johnny Lawrence, bass, and drummers Greg Donaldson or Matt Gibb.

“Inside Out hardly earned any money at all and was a bit of a floating line-up, but people were starting to get in touch to do gigs or record with them, so I became a session player. I was playing in the Christchurch Symphony Orchestra, in the New Zealand Jazz & Blues Festival, in backing bands, and blues and roots bands – all sorts of things.”

Harry’s diversification meant he mixed and played with musicians from many genres and was seen to be accomplished in numerous styles. He and his wife had parted company by now and in 2000 he was offered a place as tutor in jazz and contemporary styles at the Christchurch Jazz School by its founder and still head, Neill Pickard. Harry has been teaching there ever since, completing his degree along the way (his 34-minute honours composition is yet to be performed), riding with the school through its various format changes – diploma to degree, name-change from CPIT to Ara – guiding students through composition and performance, and working both on stage and behind the scenes with the top-line echelon of other jazz school tutors.

When the quakes of 2010-11 happened, with the destruction of venues around town, gigs were interrupted in a major way for all working musicians in Christchurch. People continued performing acoustically and those who could teach, did. Jazz school tutorials continued off-site, and this provided Harry’s base income while the city gathered itself together with earthquake repairs and reconstruction.

Pre-quake, the Jazz School had begun to offer courses in contemporary music alongside its core jazz line, and under the guidance of the Tom Rainey ONZM, head of creative industries until 2019, its remit had continued to expand.

Harry’s own music keeps morphing, in step with the changes at the jazz school.

“Over the past five or six years we’ve branched out into singer-songwriting,” Harry says, “and if laptop is your instrument, you can get involved in producing music on that. I’ve been involved in the jazz side, in the contemporary side and we also now have a one-year level four, which is between high school and tertiary. I teach performing and music writing on that certificate course level four and I take the third-year-degree students for their capstone [culminating] project. It’s a contract. They come up with the idea and we say cool, we can do that, and this is how we’re going to do it.”

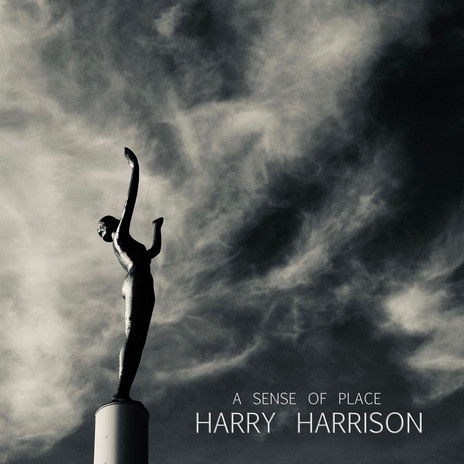

Harry’s own music keeps morphing, in step with the changes at the school and as the city’s musical life and various festivals resumed. Along with several line-ups and ongoing ensemble projects he has with his partner Justine Snelgrove (sax, flute, keyboards), he has produced a series of major audio-visual projects based on the art of four New Zealand artists: the Christchurch-born New York-based kinetic artist Len Lye (1901-1980), and contemporary artists Bill Hammond in Lyttelton, Max Gimblett in New York, and Neil Dawson, Christchurch.

Doodlin’: Impressions of Len Lye (1987), a television documentary on Lye’s life and avant-garde work, including his film Tusalava, was Harry’s initial motivation.

“I never knew about him before that and it fascinated me so much – not just that I found his art, his life and his whole concept really exciting, but because he was into art that moved, sculpture that moved, and I wondered if I could connect art with music. That’s what led me down that track.”

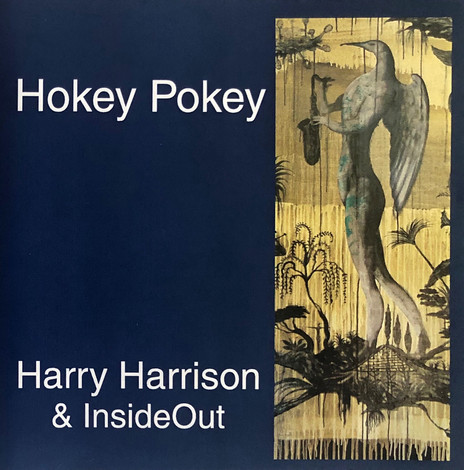

He presented his Tusalava project in 2002. Next up, in 2003, was a composition based on WD (Bill) Hammond’s large-scale acrylic on canvas painting, Hokey Pokey (1998); another in 2005 was on sculptor Neil Dawson’s Chalice sculpture, which is in Cathedral Square, Christchurch, and a piece on the work of Zen painter Max Gimblett in 2007 followed.

Harry spent time with each of the three living artists, jamming with Hammond at a friend’s place (Bill was drumming), and seeing Gimblett in Auckland and New York. “He was lovely. I spent an afternoon and had a meal with him in New York and went to his studio. He’s a spiritual kind of chap. I guess the artwork’s like a window into spirituality and existence.”

In each case the compositions were performed in concert with a jazz-based ensemble of eight or more musicians playing live to a film based on the artworks. It was, he says, “stressful but exciting”.

“You have to try and cue sections of the music to match up with the film and it never works out the same way twice. There are sections of the films where I knew certain things needed to happen, but there was always an inbuilt buffer. In other words, a musician soloed until I gave the cue or there was a little section of music that was free in structure, where we all kind of rambled, and then I’d make a cue and something else would happen. When we rehearsed, the musicians had to get a feel for how long they had, but obviously if the tempo of the earlier parts were a bit slow, then they had less time, or if they were quick they had to go for a bit longer.”

‘Last Light’, his first jazz composition, was performed with the Christchurch Symphony Orchestra.

Last Light was his first jazz composition for a full orchestra. Atmospheric and just over seven minutes in length, it was performed with the Christchurch Symphony Orchestra and featured jazz vocalist Jennine Bailey.

“Tom Rainey was putting on a show, I think it was called ‘Kiwi Jazz’, and it was to include a whole lot of arrangements by locals and include Stu Buchanan, Doug Caldwell, Bob Heinz, and everybody. I asked Tom if it would be OK if I did a composition instead of an arrangement. He showed me some faith and let me do that. I chose Jennine because I felt her voice would work really well with it.”

His band-based concert projects include Voice of the Blues and Digging the Roots for the New Zealand Jazz & Blues Festival, each featuring a strong line-up of local musicians and vocalists with arrangements of classic songs of each genre, and Midge Marsden as the headline act in “Voice”. Bon Ton Roulet was another such project, and it has life beyond the festival.

“It was specifically for the Jazz & Blues Festival, but we’ve carried on with a different piano and drums, but still keeping the rest and Steve Driver singing – purely because it was too hard to get those other guys together. They were too busy.”

As well as classical, acoustic and electric guitar, Harry plays lap-style slide, resonator, lap steel and banjo, and draws his inspiration from a wide sweep of music, from Renaissance to contemporary classical or serious music, to all sorts of jazz and Americana. All of these styles inform the music he composes and plays in his duos and ensembles with partner Justine, including the former acoustic instrumental unit, Radius, and the present one, King Tubbs.

He has also started experimenting in digital artforms as a continuation of his long-held love of the visual arts.

“It’s always been there. I wish I’d taken art at school as a subject. We were given one period a week of general art or something, and I loved it. I’ve drawn occasionally over the years and now that I’ve reached a place in life where I’ve done so much music, I’m quite happy to invest some time in the arts.”

--

Read more: Harry Harrison on Christchurch’s live scene since the mid-1980s

Watch more: Harry Harrison’s audio-visual projects