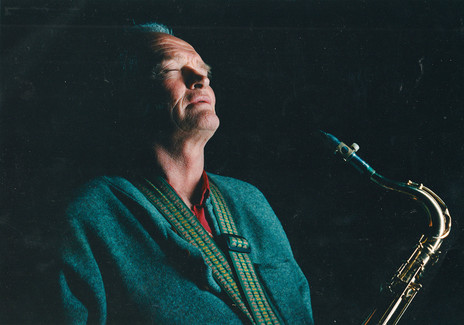

This legendary saxophonist and multi-instrumentalist – known to everyone simply as Stu – was born to play music, and his twinkling eyes and joie de vivre testified to the benefits of his lifetime pursuit. When he died, aged 83, on 4 June 2014, his death rent a large hole in the fabric of city life and the New Zealand music scene.

Stu’s life was jazz, whether gigging, listening, composing, arranging or teaching, and along the way he inspired several generations of younger musicians, many of whom are themselves doing well in the business now.

For more than a quarter-century from the 1960s he was an itinerant teacher in secondary schools and at the CSM (Christchurch School of Music), an all-ages, not-for-profit, music-tuition organisation. And 25 years ago, when fellow musician and teacher Neill Pickard founded the CPIT Jazz School at the Christchurch Polytechnic (now Ara Institute of Canterbury), as a jazz-based alternative to classical music degrees, Stu was on the original panel of advisors.

He was influential in introducing stage bands at the CSM and secondary schools as a practical means for students to learn on the job – a method that served him well along his own path – and he was the musical director of the popular Garden City Big Band from 1997 until 2012. He continued to play with the big band after relinquishing leadership and, in 2013, recorded his album, Hey! What’s the Time?, backed by Garden City.

Stuart Duncan Buchanan was born on 18 November 1930 on “Waione” in the King Country, a BNZ-owned sheep station his farming father managed midway between Te Kuiti and Taumarunui. Back then, the surrounding bush was in constant flux, as timber-milling companies felled and cleared the bush for pasture and burnt the woodchip scraps.

“I remember scanning the horizon on winter evenings,” he told Wilson Reveley in 1999. “The atmosphere was always blue with rimu timber smoke and the air heavily accented with slab-heap rimu scent.” (He was speaking to Reveley for a University of Canterbury sociology paper titled “Sax Education – The Musical Evolution of Stu Buchanan: Jazz Muso & Educator”.)

On still days the dawn chorus from the bush was spectacular

On still days the dawn chorus from remaining bush was spectacular and other melodic notes issued from the Buchanan household, making a strong impression on Stu and older brother Don. They enjoyed singing together at school concerts and family get-togethers, and once they found they could sing simple harmonies, they would fight – sometimes literally – over who would harmonise and who would sing lead.

Stu sang and whistled constantly – tunes he made up or heard on the radio – and both parents had natural musical talents and inclinations. His father was a “bathroom baritone” and his mother, Tui (née Ashby) taught herself piano and violin from tutorial books. The boys grew up listening to her work through the classics with a deft touch.

“Though self-taught she could read music pretty adequately,” Stu wrote later (in an unpublished biographical essay), “and seemed hugely capable as an ‘ad lib’ musician, willing to accompany any performers in just about any key …”

Tui organised piano lessons for Stu, but he lasted only three months at it. “I was pretty reluctant,” he told Reveley. “I was just an ordinary sort of a kid who wanted to go bird-nesting or play cricket or something …”

He hated the structured lessons and instead found his own way into music, with inspiration sparking at 12 after hearing the dixieland jazz of Bob Crosby’s Bobcats on an old wind-up gramophone. Jazz became his doorway to musical pleasure and he was hooked.

The family moved when Gordon Buchanan began managing another farm, and again as he bought two of his own. Just before the Second World War began, Stu found himself at Glenbrook Primary School in South Auckland. Pukekohe Technical High School followed. “I was no scholar,” he wrote with emphasis.

He quelled his ennui long enough to achieve School Certificate and left school when he was 17. Freed from curricular restraint he found his real school in the jazz clubs of Auckland, soaking up the sounds and atmosphere by night while holding down various farm-labouring jobs by day. Adept at several different instruments, including tin whistle, by the 1950s he was playing in local bands.

“… Immediately I left school and went to a city I found kindred spirits everywhere,” he told Reveley. “The first gig I ever did, I think, was at Matakawau, a place on the Awhitu Peninsula, and I played acoustic bass.” His fingers bled and he “found it a bit onerous” – but things looked up when he was 21.

“I rode my motorcycle to Auckland and bought a silver-lacquered tenor saxophone”

“I rode my motorcycle to Auckland, walked into Lewis Eady & Co and bought a ‘STAR’ silver-lacquered tenor saxophone off the wall for £65 secondhand. With a borrowed tutor book I entered my bedroom with the sax at about 10.30am one day and re-emerged about 1.30am next day. I was nutty about the sax.”

Behind closed doors he worked hard on his chops, emulating jazz licks he heard on records or radio and by watching jazz players in the clubs.

“In retrospect,” he wrote later, “I feel lucky that formal education didn’t enter in the first love affair with music, where I developed my own terminology for scale intervals and diatonic melody bits and pieces. Later, of course, I built on this elementary approach and since then have always [sic] been able to find someone who knows more than me when I need to understand something new.”

Keen to stretch his technique, he joined Franklin dance band Bulte’s Orchestra, playing along with the melody, like the other band members, and having fun in the process. “You had lots of time to indulge in fingering errors.”

At 24, Stu headed to the South Island in pursuit of work and, for the next decade or more, he earned good money shearing and as a freezing worker around Southland and the Maniatoto Plain.

“In the boarding establishment of the freezing works just about every branch of humanity from murderers to parsons’ sons seemed to be represented. Man, incredible people! The violence and the gambling – I had never seen anything like it.”

By 1957 Stu had met and married Invercargill girl Marie Harpur and they moved to a small farm in Ohoka, on the outskirts of Christchurch, with a few sheep, some poultry and a paddock of potatoes. He worked the farm during the week and sought out jazz wherever he could find it, playing in district dance bands every weekend. Their two sons, Lyn and Kere, would grow up to be professional drummers, well regarded on both sides of the Tasman.

HE FARMED DURING THE WEEK AND SOUGHT OUT JAZZ WHEREVER HE COULD FIND IT

Although Stu was not to know it at the time, this move was a major signpost. He remained in Canterbury for the rest of his life, expressing the full range of his creative abilities from his base in Christchurch.

In 2012 Stu and Neill Pickard were interviewed by Chris Bourke for the Radio New Zealand series Blue Smoke. Stu talked about his early days in Christchurch, fellow musicians and major influences.

“I remember walking up the stairs of the Union Rowing Club, I think in 1958, and asking Martin Winiata whether I could play the saxophone. He was a most amenable guy and he said, ‘Sure!’ The band … consisted of Doug Caldwell, piano, Lester Winfield on bass, Coral Cummins singing, and a returned vet surgeon by the name of Mike McMullin playing drums. That was my first night in Christchurch … and it was wonderful fun.”

The pace of Stu’s working life in music picked up exponentially, as he met and worked with all the key players in Christchurch’s lively jazz scene – jamming, playing with dance bands, and eventually earning a spot in a coveted live-to-air radio-band gig through the influence of one man in particular:

“This was Chook Fowler. Everyone called him Chuck, but he was John Fowler,” Stu told Bourke. “He was a piano player, went to Timaru Boys’ High School. … I remember him approaching me in a pub with a fistful of hand-written charts, saying, ‘I’m auditioning for a big band for 3YA. There’s the tenor charts, get it down’. So I went home and read the first middle C of my life.

“Chook Fowler, Harry Voice, Dave Easterbrook, Dennis Bryson – that seemed to be the nucleus of people. … We met every Saturday at somebody’s house, drank a lot of beer and played ‘A Foggy Day in London Town’, and the fifth chorus was better than the first one, so that was our learning scenario.”

That first radio band was the Brian Marston Band. “Brian and Doug Kelly used to alternate. They did 10-week programmes, one after another. It went on for years. They used to write the charts, rehearse them down at 3YA, and go out live.”

Brian Marston was a kingpin on the southern jazz scene, and playing in the band was aspirational for any up-and-coming player. “He was Mr Music in Christchurch and deservedly so,” Stu told Reveley. “It was a closed school; it was like an old man’s home and to get in there someone had to go out. It was a political hot potato.”

But Stu had earned his foot in the door. “I came in and played a couple of tunes with the rhythm section … and you got pounds, shillings and pence. Doug Caldwell was the pianist. He wrote on-the-spot chord charts for the occasion – no extra charge. He is a magnificently able and helpful musician.”

The radio-band gigs were hair-raising for their on-the-spot pressure

By now, Stu was doing a crash course on the job, developing both his chart-reading and improvisational skills. The radio-band gigs were hair-raising for their on-the-spot pressure: “The red light went on and you were on air – you played it. Great training ground, really – goof-ups and all, but surprisingly accident-free over all,” he told Reveley. “You never play well, you just play correctly.”

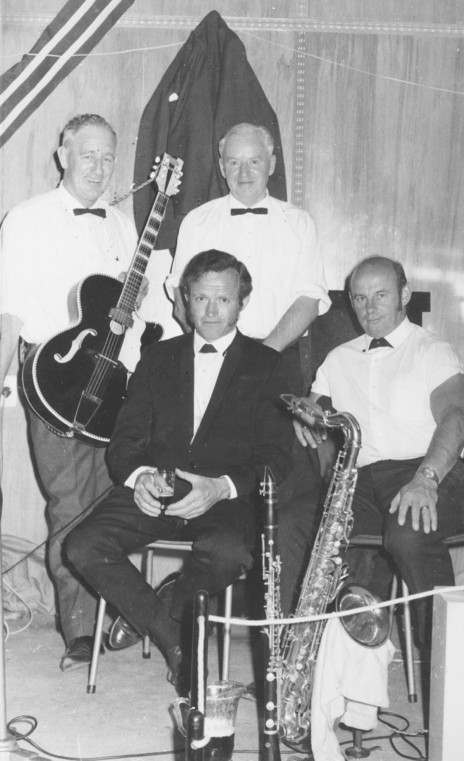

Pianist Doug Caldwell’s workload at that time was inspirational, and he was writing, arranging and performing with his jazz trio, quartet, Latin dance band or orchestra, and Stu participated in most of these bands: live or on radio. They were still working together until Stu’s last few months.

The Bob Bradford Big Band was another key influence, and Stu worked with the band for several years on radio and during its residency at the (pre-quake) Carlton Hotel in central Christchurch.

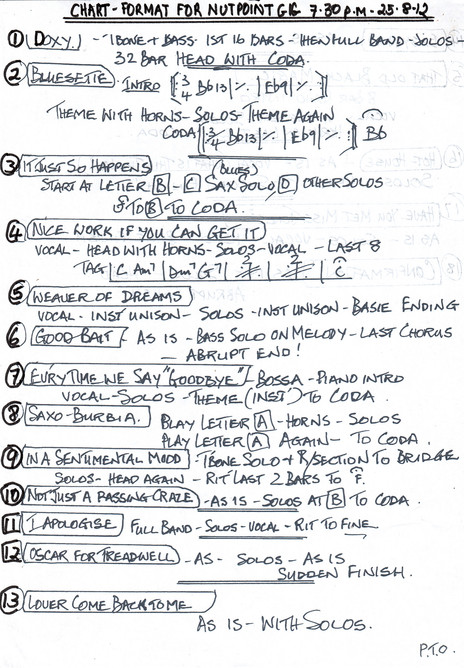

By the 1960s, the gigs were coming thick and fast. There were pubs, clubs, cabarets, dances, balls, live-to-air radio concerts and recordings all over Canterbury. Months and years from his jam-packed diaries tell the tale. March 1962, for example, reads: Mar 2, Belfast Country Club; Mar 9, 3YA – Doug Kelly (day), Belfast Country Club (night); Mar 10, 3YA – Brian Marston; Mar 15, 99 Club – Lester Winfield; Mar 16, Belfast, then Brighton Pub; Mar 23, Brighton & Belfast; Mar 30, Brighton & Belfast.

During these years Stu also travelled further afield, meeting and working with top jazz musicians from New Zealand and Australia, including the likes of Julian Lee, Dale Alderton, Calder Prescott, Bart Stokes, Don Burrows and George Golla.

In the late 1960s an employment opportunity arose for him in teaching music at secondary schools. “I was a culture-shock victim. … I came from off the turnips, you might say, into this cultured environment,” he told Reveley.

He decided to back up his practical instrumental skills by putting himself through his letters, and gained an LRSM and an LTCL in flute and clarinet. Originally hired to teach clarinet, he was soon teaching flute, saxophone and trumpet, as well as creating stage bands so his students would have an outlet in contemporary music and jazz.

Stu Buchanan was married to Marie for some 30 years, then for his last 22 years his partner was Jill Fenton, a trombonist who grew up in Wellington with music, singing in the Henry Rudolph Singers before moving to Tauranga. Her father played in dance and brass bands and her husband was a trumpet player. She told me how Stu’s autodidact streak was prominent in many areas of his life, including teaching himself te reo.

“He loved the Māori language and was very fluent in it,” she says. “His grandfather could speak it … Stu used to sit there and listen to him speaking it when he was little. He always loved the sound of the language and really taught himself it. He sat in on a university course down here at one stage, too.”

He could play bass, saxophone, clarinet, flute, trumpet, tin whistle, piano.

Stu also loved singing: “He sang a lot. He had a vocal group years ago and they did very well. Four-piece, close harmonies – he loved it. He also played bass with Doug [Caldwell] at one stage. He could play bass, saxophone, clarinet, flute, trumpet, tin whistle, piano. He spent a lot of time playing the piano in recent years, his last 10 years.”

Despite the shortage of venues in the aftermath of the Canterbury earthquakes, musicians found ways to keep working.

“Stu did lots of gigs – weddings, birthdays, concerts – small groups, singing at them as well,” says Fenton. “He was pretty busy right up until a couple of months before he died.”

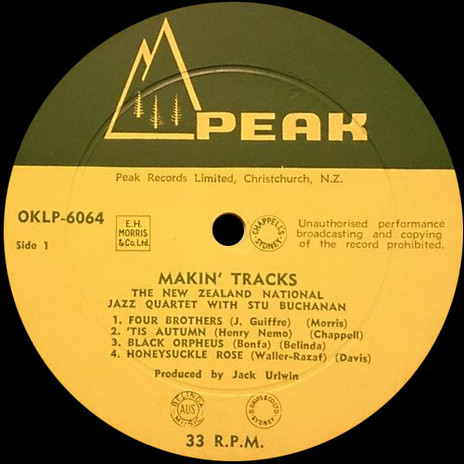

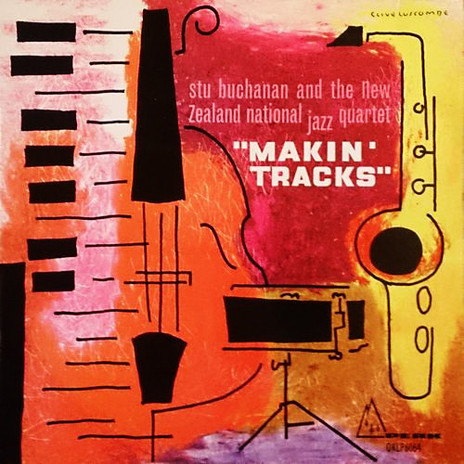

During his career, Stu made several albums. The first was Making Tracks, for the Peak label in 1966, with the New Zealand National Jazz Quartet (this included well-known Christchurch jazz names such as Nick Nicholson, George Campbell and Harry Voice). With The Golden Saxophones – an instrumental group formed and led by Stu – he was behind one of the biggest selling LPs in New Zealand history. 22 All Time Favourites was a compilation of standards commissioned by Music World in 1978 and, with heavy TV advertising, allegedly sold 600,000 copies worldwide.

In 1989 The Silver Saxes of Stu Buchanan released The Beatles Revisited (Hibiscus) – jazz versions of early Beatles songs, on which he was accompanied by younger Christchurch musicians such as Tom Rainey, Tom van Koeverden and his son, the drummer Kere Buchanan. And in 2013, with the Garden City Big Band he released Hey! What’s the Time?.

Stu Buchanan was awarded an MNZM in 2002 for services to jazz and music education. He wrote about being “part of the local ‘furniture’” in Christchurch, where he was able to express his affinity with music from the Great American Songbook.

“I’ve participated almost solely in the dance band world and feel an adherence to the music of Irving Berlin, Jerome Kern, the Gershwin brothers, Cole Porter, Hoagy Carmichael, Duke Ellington, Richard Rodgers, Harry Warren, Jimmy van Heusen etc. … I was very attracted to the jazz playing typified by the ‘Boppers’ – Dizzy Gillespie, Charlie Parker, Thelonious Monk, Gerry Mulligan, Chet Baker, Cannonball Adderley, Dave Brubeck. That’s all gone, too, however. Time marches on. I guess I’m now attracted to 21st century exponents of classical music. Many good examples of this writing art are present in New Zealand. We live in interesting times.”

Stu Buchanan was good company, with an interesting turn of phrase and a singular way of looking at the world. He was a long-time friend of many and always up for a laugh. That he was both loved and admired was apparent in the outpouring of emotional tributes in print, in person and on social media following his death, and by all who gathered at the wake to pay their respects, share tall tales and reminiscences, and take their turn on stage to pay musical homage to the man. Stu Buchanan was an original and there will not be a replacement for him any time soon.

--

Read Stu Buchanan on his peers and mentors

Thanks to Jo Jules for permission to use several archival photos from her book A Passion for Jazz: the Christchurch Scene then and now (CPIT, 2009).