Neill Pickard

Some people walk through this world unnoticed, while those who choose music and communication arts are always in the spotlight. Such is the case with Neill Pickard – musician, academician, humanitarian, gentleman. Whether teaching, playing music or working behind the scenes, words and music are ongoing motifs in his personal and professional life.

Neill has influenced countless secondary school students during a career-long occupation teaching French, music, and English as a Second Language. He has lectured in music history to tertiary students, composed and directed a full-scale rock-jazz musical based on the life of Shakespeare, and continues to work as a singer and musician in a Dixieland jazz band as well as other genre line-ups.

River City Stompers in the studio, Christchurch 1963. Dave Innes (drums), Les Brown (trumpet), Tony Lewis (trombone), Paul Dyne (clarinet), Neill-Pickard (banjo).

Photo credit:

Neill Pickard Collection

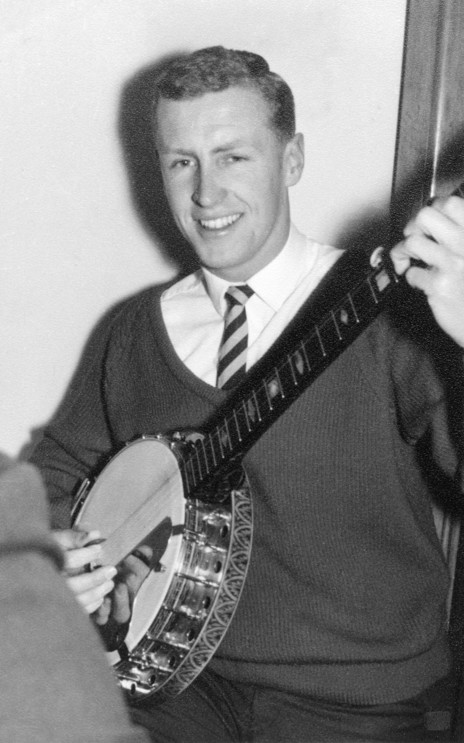

Neill Pickard with banjo, 1963.

Photo credit:

Neill Pickard Collection

River City Jazzmen live, 2018

My Grandfather's Clock - Larry Marschall, Tony Hale and Neill Pickard

Neill Pickard's first guitar, a 1958 Ermelinda Silvestri, built in Catania, Sicily.

Photo credit:

Neill Pickard Collection

Neill Pickard with Manhattan Transfer, Christchurch Town Hall 2005.

Photo credit:

Neill Pickard Collection

Neill Pickard receiving QSM honour from NZ Governor-General Anand Satyanand, 2008.

Photo credit:

Neill Pickard Collection

Neill Pickard with Emile Grimshaw, banjo, 1964.

Photo credit:

Neill Pickard Collection

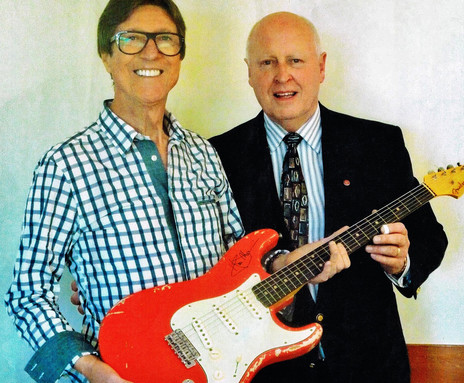

Hank B Marvin of The Shadows signs Neill’s Stratocaster.

Photo credit:

Neill Pickard Collection

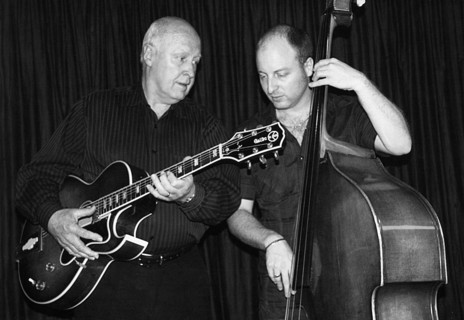

Neill and son Richie Pickard on double bass, April 2008.

Photo credit:

Neill Pickard Collection

Therese and Neill Pickard at Neill's QSM honours ceremony.

Photo credit:

Neill Pickard Collection

Undergrads publicity photo, taken on the roof of a demolished building in Hereford St Christchurch. Left to right: Neill Pickard, John Brock Miles Reay Dave Innes.

Photo credit:

Neill Pickard Collection

Lloyd & the Undergrads, Caroline Bay, 1963. (From left) drummer Dave Innes, Neill Pickard, Lloyd Scott (in long trousers), John Brock, and Miles Reay.

Photo credit:

Neill Pickard Collection

Jazz school staff, 1992. Back row, left to right: Neill Pickard, Murray Warner, Bob Heinz, Tom Rainey, Ted Meager, Gerald Marsden (trumpet); middle: Ian Edwards, Doug Caldwell; front: Genevieve Kelly (voice and choir) and Sharon Moynihan.

Photo credit:

Neill Pickard Collection

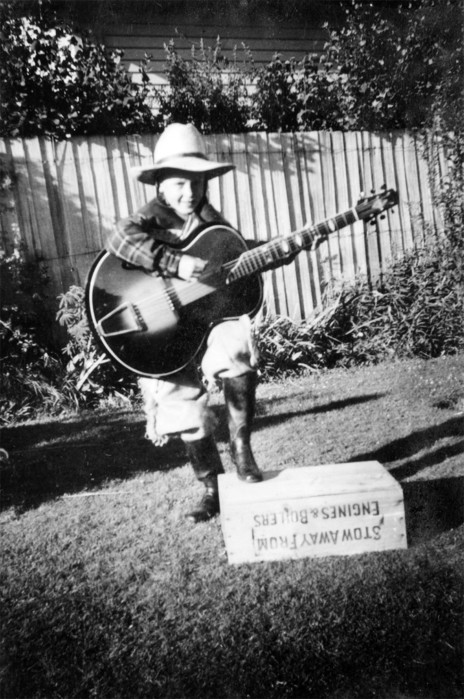

Neill Pickard, singing cowboy.

Photo credit:

Neill Pickard Collection

Redwing - Larry Marschall, Tony Hale and Neill Pickard

Neill Pickard and his son Antony.

Photo credit:

Neill Pickard Collection

The River City Jazzmen - Putting on the Ritz

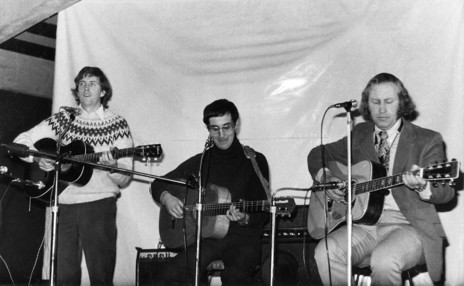

Folk trio, late 1970s. Hugh Canard, Steve Dakin, Neill Pickard.

Photo credit:

Neill Pickard Collection

"Dippermouth Blues" River City Jazzmen Live @ Orange

Neill Pickard's 60th, with his sons Antony and Michael.

Photo credit:

Neill Pickard Collection

Neill Pickard receiving Civic Honour Award with Christchurch Mayor Bob Parker, 2008.

Photo credit:

Neill Pickard Collection

Neill Pickard in class at CPIT, 1980s.

Photo credit:

Neill Pickard Collection

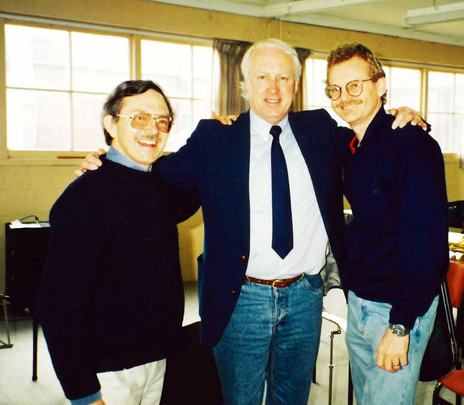

Ian Edwards (left), Neill Pickard and Brent Stanton, a former pupil of Stu Buchanan and Ian Edwards, and a regular in Ian’s band. A Sydney Conservatorium graduate, Neill describes Brent as “a monster reed and flute player who went to New York; an Emmy arranger, among other feats”.

Photo credit:

Neill Pickard Collection

Neill Pickard, Larry Marschall and Tony Hale live, Christchurch Folk Club.

Neill Pickard jamming with Acker Bilk.

Photo credit:

Neill Pickard Collection

“Nothing’s Too Hard for Neill Pickard” by Gerard Masters (2017)

Neill Pickard in gig mode, 1963.

Photo credit:

Neill Pickard Collection

"Sweet Georgia Brown" River City Jazzmen Live @ Orange

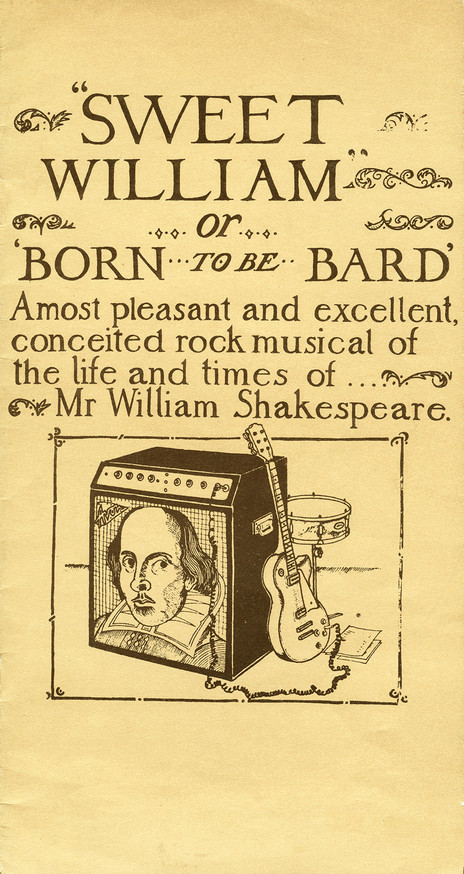

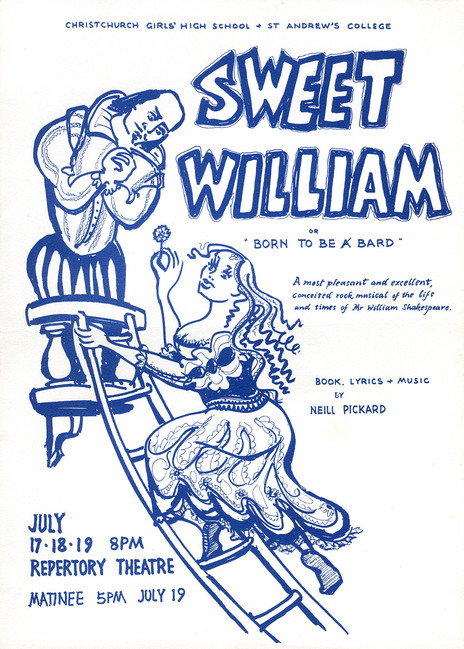

Poster for Sweet William, a rock-jazz musical based on the life of Shakespeare, composed and directed by Neill Pickard.

Photo credit:

Neill Pickard Collection

Jazz school tutors, 1993. Back row (left to right): Tom Rainey, Ted Meager, Neill Pickard, Doug Caldwell, Bob Heinz; front row: Ian Edwards and the late US jazz trumpeter Nat Adderley, who did the narration for Porgy & Bess with CPIT Jazz School choir & leads.

Photo credit:

Neill Pickard Collection

Neill Pickard in Red Hot & Dixie.

Photo credit:

Neill Pickard Collection

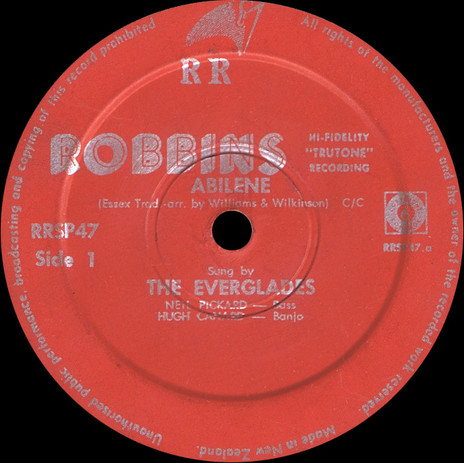

The Everglades - Abilene (Robbins Recordings, RRSP47, 1964) - Hugh Canard, bass; Neill Pickard, piano.

Larry Marschall, Tony Hale and Neill Pickard - Caravan

Neil Pickard, John Wilson, and Michael Lawrence, mid-1970s.

Photo credit:

Neill Pickard Collection

The Undergrads with singer Susie DeMaria, Ilam Homestead.

Photo credit:

Neill Pickard Collection

River City Jazzmen at Nut Point Gallery, November 2018. Left to right: Jerome Raateleand, Neill Pickard, Dave Pitt, Michael Fairhurst, Tony Lewis, Allan Hawes.

Photo credit:

Neill Pickard Collection

Poster for Sweet William, a full-scale rock-jazz musical based on the life of Shakespeare, composed and directed by Neill Pickard.

Photo credit:

Neill Pickard Collection

Neill Pickard on contrabass with Barry Brinson at the piano.

Photo credit:

Neill Pickard Collection

Lloyd & the Undergrads, 1963. Miles Reay (left), Lloyd Scott, Neill Pickard, and Dave Innes (obscured).

Photo credit:

Neill Pickard Collection

Turkey in the Straw - Neill Pickard, Larry Marschall and Tony Hale live, Christchurch Folk Club.

Labels: