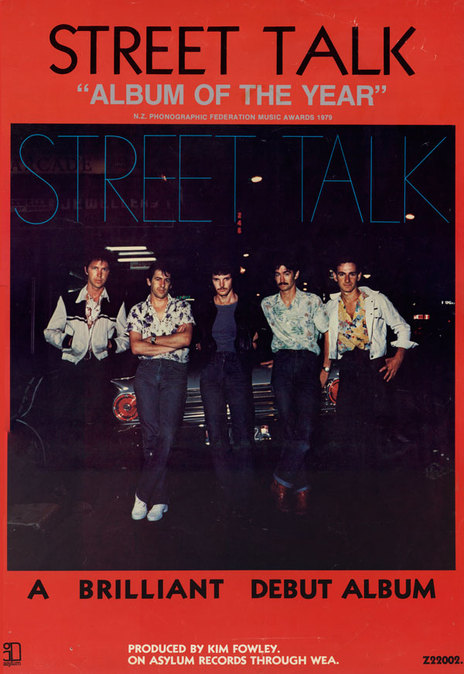

At the Windsor Castle they were seen by former Byrd, Chris Hillman. That led to their involvement with Kim Fowley, Svengali producer of Los Angeles. He tried to turn them into an antipodean Bruce Springsteen & The E Street Band.

“Musical differences” split Street Talk apart in 1980 at the end of their only national tour, but the band members enjoyed long careers in New Zealand or Australia either solo, as session musicians or in bands such as Dave McArtney & The Pink Flamingos, Hello Sailor and Mental As Anything.

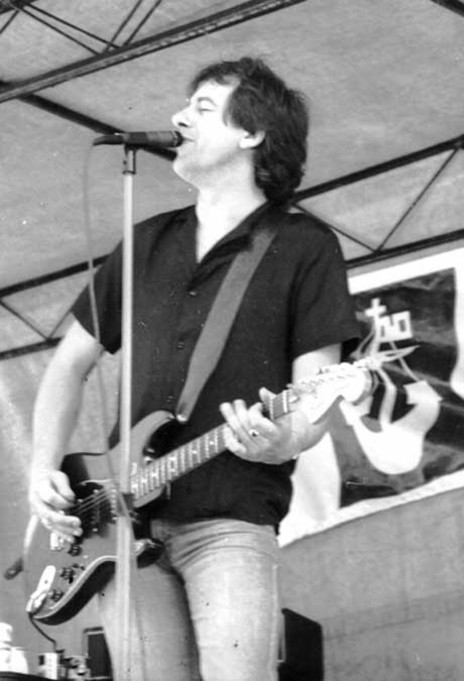

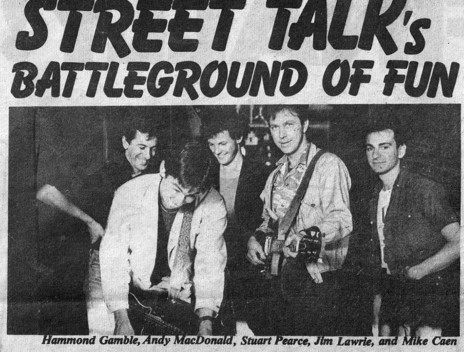

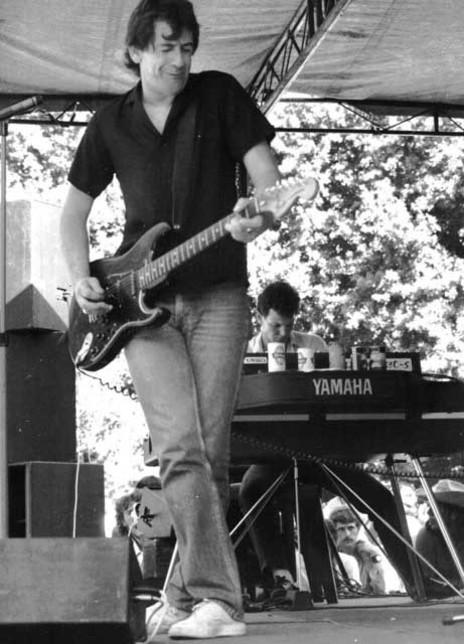

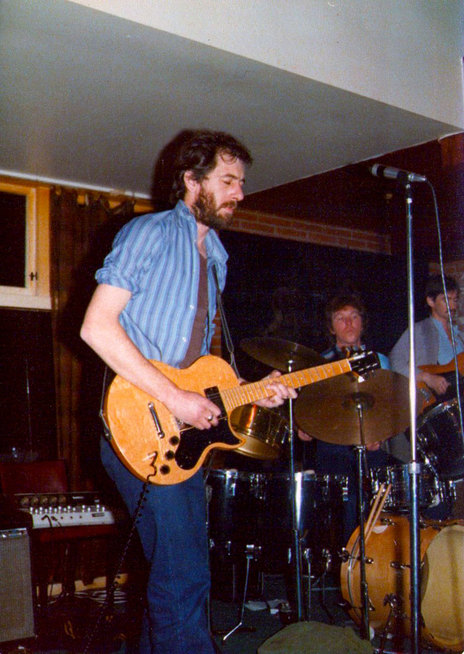

In mid-winter 1974, Auckland bass guitarist Andy MacDonald found himself at a low-key Northland music festival where he was floored by the blues playing of pick-up Whangarei guitarist Hammond Gamble. MacDonald told the shy Gamble that he should chance his arm in the big city.

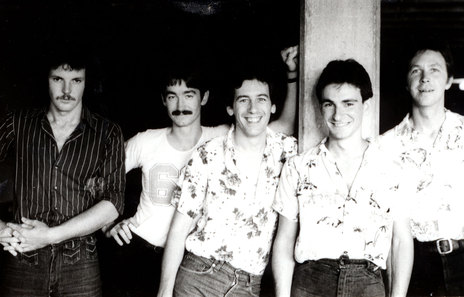

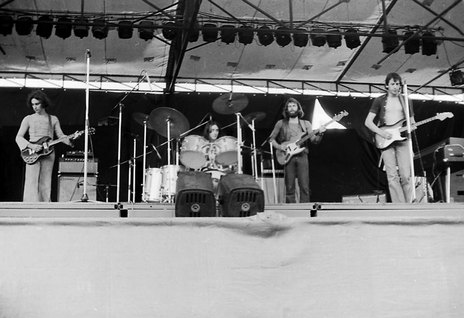

Gamble decided to do just that, arriving in Auckland weeks later where he, MacDonald and Walter Ormsby (drums) formed Street Talk. Their first gig was at the Pukekohe Hotel in August but Gamble soon negotiated a Tuesday night residency at the Windsor Castle. Pub manager Kevin Lane was so impressed with the turnout that the residency grew to two nights and then three and eventually six nights a week.

Caen’s dirtier guitar sound complemented Gamble’s clean style and the guitarists clicked.

Early in the new year, MacDonald invited guitarist Mike Caen to a Street Talk rehearsal and he joined the ranks. Caen had been with progressive rock jam band Elysium and had even spent three weeks in Split Enz, which amounted to being driven to practices by Tim Finn because Caen’s mother wouldn’t let him take her car. Anyway, Caen was a Clapton fan and the Enz were Beatles freaks, so it didn’t work out.

Caen’s dirtier guitar sound complemented Gamble’s clean style and the guitarists clicked. The Windsor residency was still going strong when Street Talk disbanded in October. Andy MacDonald joined Hello Sailor but not for long, rejoining Street Talk the following January when they returned to the Windsor Castle with a hefty pay rise and new drummer Steve Butler.

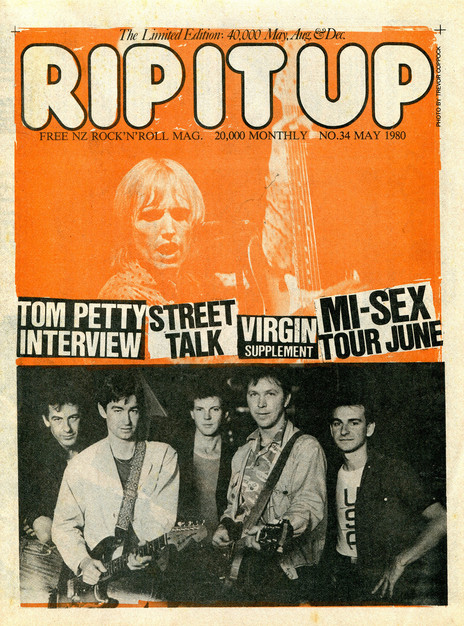

But MacDonald left in June to try his luck in Sydney, where he recorded an album with glam rock band Australia. A Band File entry in Rip It Up from June 1979 says he was sacked from Australia “for falling asleep on stage” (see link below). His replacement in Street Talk was singer-songwriter-bassist Malcolm McCallum.

Caen ventured to Australia in early 1977 before heading to London in the middle of the year. By April, the Street Talk line-up was Hammond Gamble, drummer Brent Eccles and bassist Peter Cuddihy (both ex-Space Waltz) and keyboardist Andrew Kay. When Gamble himself opted out, they changed their name to Vox Pop.

Gamble and wife Sue relocated to his Lancashire hometown of Bolton-Le-Sands for a year. When they returned to Auckland, Gamble found an energised band scene with Hello Sailor leading the way and newly dedicated venues like the Gluepot packing in big crowds.

He called in to the Windsor Castle, where Rockinghorse were in their death throes playing to a half-filled room. Their drummer was Gamble’s former Whangarei high school mate Jim Lawrie. After leaving Northland, Lawrie had played and recorded with Highway and Midge Marsden’s Country Flyers. When Kevin Lane told Gamble there would be a gig at the Windsor for a re-formed Street Talk, Lawrie was quickly recruited.

Bassist Andy MacDonald was welcomed back and Gamble got a message to Mike Caen in London telling him of the boom in Auckland. It didn’t take much coercing: returning home sure beat living in a squat waiting for The Rolling Stones to find out who he was and giving him a call.

A Byrds reunion of sorts brought Chris Hillman, Roger McGuinn and Gene Clark to New Zealand in June 1978 and somewhere along the way Hillman caught a Street Talk gig. He put a call in to his New Zealand label head Tim Murdoch at WEA and advised him the company should finance a Street Talk single and he would produce it.

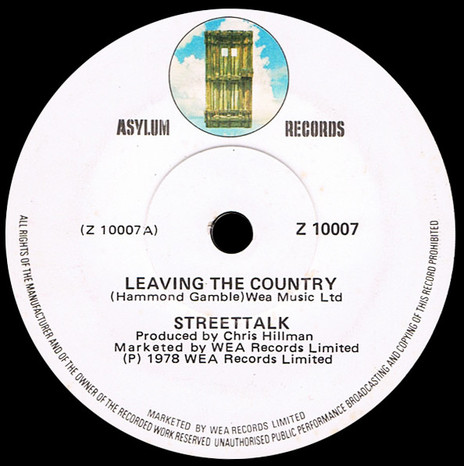

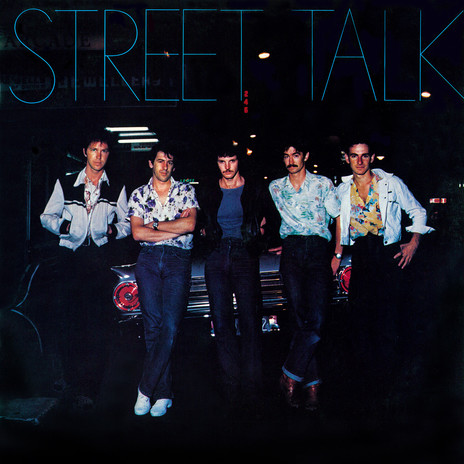

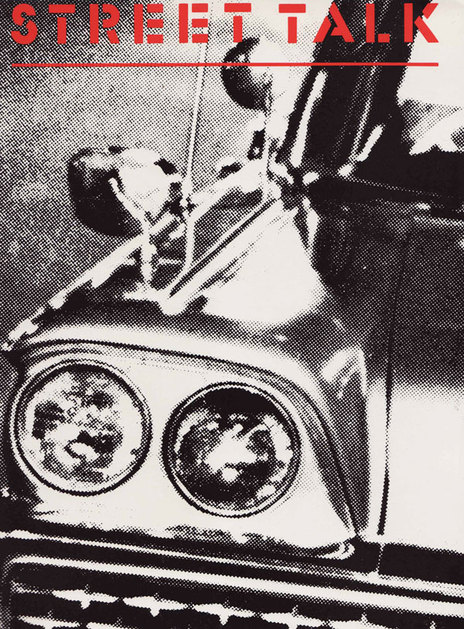

Murdoch agreed and the band convened at Stebbings. The resulting single ‘Leaving The Country’ b/w ‘Fallin’ To Pieces’ (both Gamble originals) was released on the Asylum label. The single disappeared quickly but copies were in the right places at the right times when LA music man Kim Fowley turned up alone in Auckland on what was supposed to be his honeymoon.

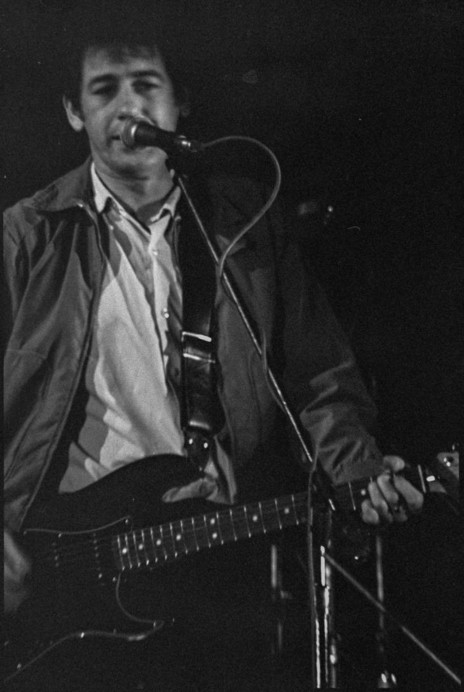

Fowley was on a mission to discover a New Zealand Beatles. He called on 1ZM programmer Peter Fyers and Mandrill Recording Studios boss Glyn Tucker and listened while the men played tracks from every current New Zealand band from Hello Sailor and Th’ Dudes to Citizen Band and Alastair Riddell. But it was the voice of Hammond Gamble and the Street Talk 45 that “smelt like money”.

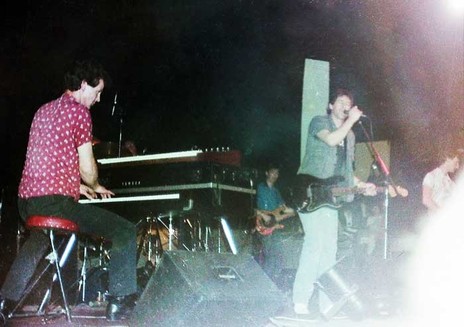

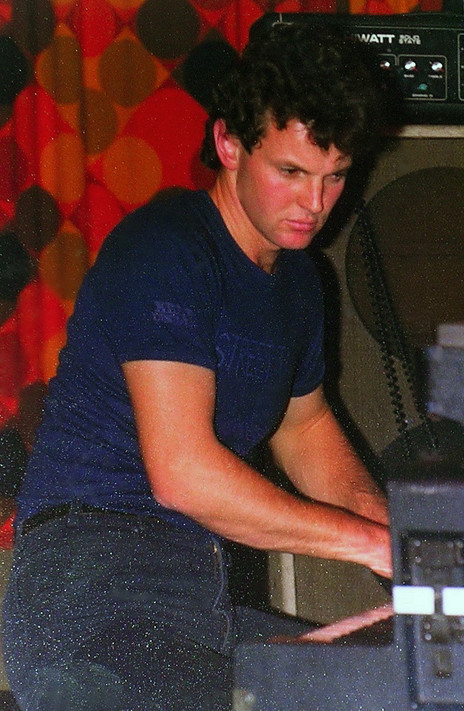

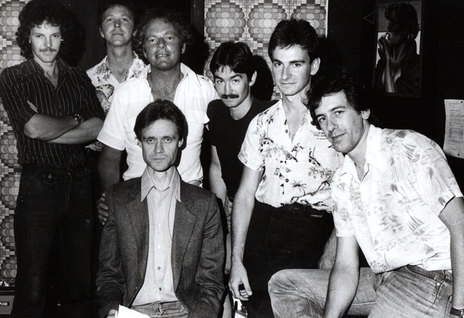

Tucker took Fowley to see the band at the Windsor Castle. After the gig, they all adjourned 200 metres down the road to Mandrill and began recording. Fowley instructed Caen to play the riff from The Velvet Underground’s ‘Sweet Jane’. He then told Caen to play it backwards. Caen’s reverse riff became the basis of the album’s eventual opening song ‘Street Music’.

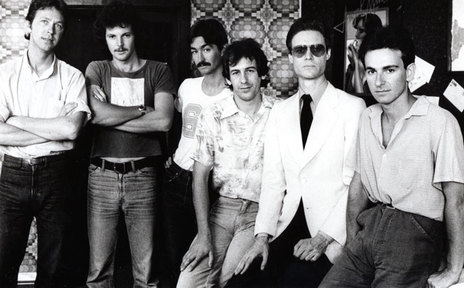

The band gained a new member when Fowley announced that Bruce Springsteen & The E Street Band had keyboards, so Street Talk would feature them too. And he found a top-notch keys player in the next room, in the form of Mandrill engineer Stuart Pearce. Pearce describes his recruitment as not so much joining Street Talk but being inflicted upon them.

Before the sessions, Gamble was the only member trying his hand at writing songs. He offered up ‘Poison’, ‘Lazy Pauline’ and ‘She’s Worth Her Weight In Diamonds’, but the remainder came from Fowley inserting lyrics around the guitarists’ riffs and chords. When he could see the band tiring, he suggested it was time for a reggae feel and they wrote ‘Short Stories’.

Just over a week later the self-titled album was recorded and mixed; in a month, it was in the stores.

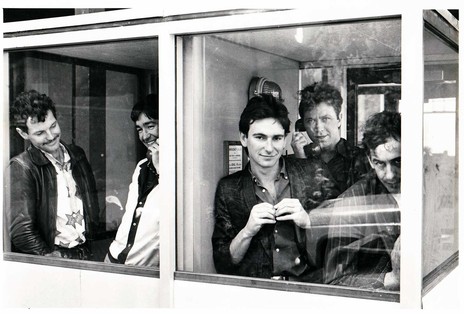

The band then sat back as Fowley went through his contact book and rang and recorded the reactions of everybody from Robert Hilburn of the LA Times, to Dave Marsh of Rolling Stone, to record companies and magazines and even Bruce Springsteen himself, as he waxed lyrical about the new Beatles he had discovered in New Zealand.

Just over a week later the self-titled album was recorded and mixed. A month later, it was in the stores. The singles ‘Street Music’ and ‘Poison’ followed in March and June. Caen knew they were doing something right when he bought a block of butter from the dairy to find that the newspaper it was wrapped in contained a review of the Street Talk LP.

Although they’d made only sporadic trips outside of Auckland, in July, Street Talk crossed the Tasman for three weeks. As well as catching up with the newly resident Hello Sailor, they played a handful of shows in Sydney before driving to Melbourne. When they arrived for their gig halfway between the two cities they found they had been double booked with Sydney pub-rockers The Radiators. Both bands played.

Meanwhile, Caen had fallen for Idle Idols bass guitarist Leonie Batchelor and his fledgling songwriting was taking more of a new wave direction than the blues and boogie of Hammond Gamble. Returning home after one Street Talk gig, The Idle Idols refused Caen entry into his flat because they were being filmed by current affairs show Eyewitness.

The plan was always for Kim Fowley to return to Mandrill to record Street Talk’s follow-up album. At the beginning of 1980, the band’s new manager, Cook Street Market impresario Brian Jones, flew to the States to gauge international interest and nail down Fowley. When Fowley’s demands grew too one-sided, Jones ended the relationship.

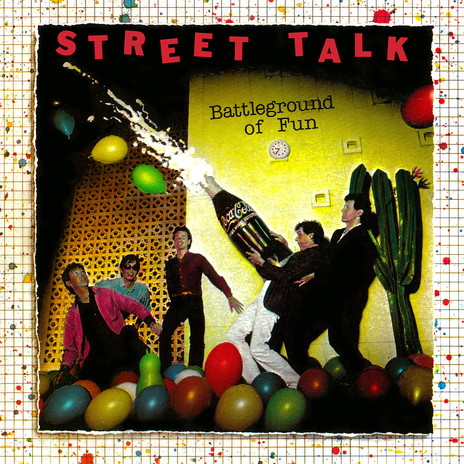

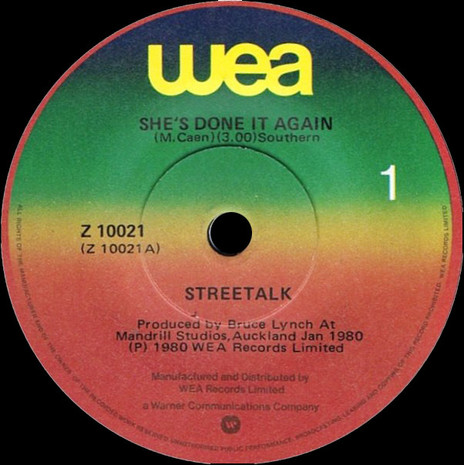

Street Talk went straight into the new Mandrill premises to record tracks for their second long-player with producer Bruce Lynch, back home after several albums and two world tours with Cat Stevens. Caen’s ‘She’s Done It Again’ b/w Gamble’s ‘Long Night Blues’ was released as a single, though neither would appear on the LP.

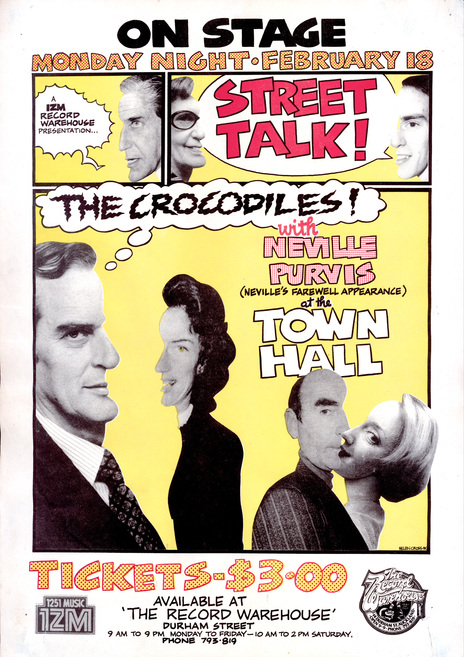

Whereas the production on Street Talk was dense and live-sounding, Lynch’s production on Battleground of Fun was crisp and clear and allowed the songs to breathe. The same was true of the handful of songs the band self-produced for the upcoming Geoff Murphy feature film Goodbye Pork Pie.

The Street Talk songs had been crammed full of Kim Fowley’s faux-Springsteen lyrical imagery, but writing duties for the second LP and the movie were shared; of the 19 new recordings, 11 were written by Gamble, six by Caen and two by Andy MacDonald.

And it was the opposing directions of the songwriters that was troubling Hammond Gamble. The distance from Caen’s new-wave-ish ‘China Girl’ and ‘Queen Of The Party Line’ to Gamble’s ‘Lonely At The Top’ and ‘Leaving The Country’ and MacDonald’s ‘The Lonely One’ and ‘Feminine Minds’ was just too far, he thought.

Towards the end of Street Talk’s gruelling first national tour, Gamble fell ill and the last three or four shows were cancelled. While recuperating at home, he decided to strike out on his own and started recording a solo album. Street Talk bowed out at a packed Gluepot in September 1980.

By the time Goodbye Pork Pie was released to theatres in February 1981 with its radio announcer proclaiming Street Talk as “one of New Zealand’s hottest bands”, they were but a memory.

Hammond Gamble and Stuart Pearce were by then in The Hammond Gamble Band, Mike Caen and Andy MacDonald were two-thirds of Blind Date and Jim Lawrie was part of Dave McArtney & The Pink Flamingos, who had just released their debut LP – all three bands taking full advantage of a live scene initiated by Street Talk six years earlier.