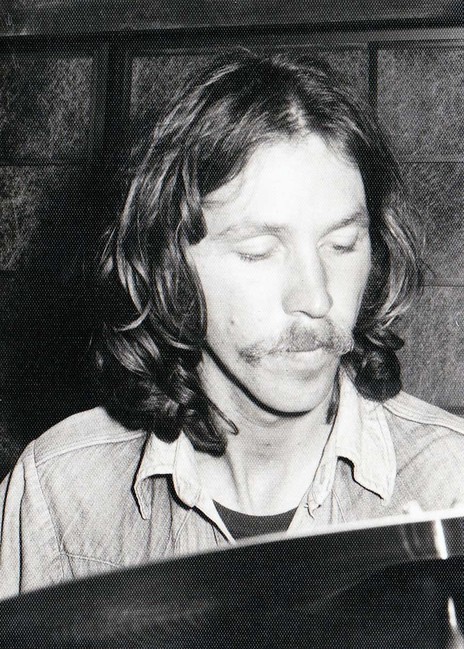

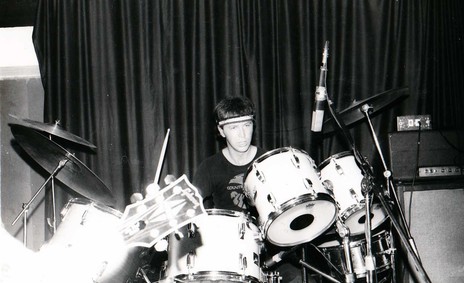

Jim Lawrie was born in Wellington on 29 May 1951 and raised in the eastern suburb of Seatoun. Young Jimmy was forever banging pots and pans. His Scottish father solved the annoyance by sending him to the Wharfsiders Junior Scots Pipe Band and in 1965 he bought his son a £15 drum kit.

“It was an Autocrat kit, cheap, with calf skins instead of plastic. When we played The Catacombs in Lower Hutt, which was hot and sweaty, the skins slackened so much it was like hitting tea towels.”

Lawrie’s first band, formed with neighbour Phil Pritchard on guitar in 1966, was Inner Sound but Lawrie and Pritchard soon joined The Urchins, R&B enthusiasts who played suburban Friday night dances, covering the likes of Paul Butterfield, The Pretty Things and Tom Rush. In mid-1967 the Lawrie family shifted to Whangarei where Jimmy, reluctantly attending Whangarei High School, met a young guitarist named Hammond Gamble, starting a lifelong friendship.

Before year’s end, established Northland band The Clan had split in two, with half morphing into Serenity Lane, adding Jim Lawrie They played current hits around the Northland dance halls and won the regional finals of the 1968 Battle Of The Bands. At the end of 1969, on holiday in Wellington, Lawrie was reunited with Phil Pritchard and decided to remain in the capital.

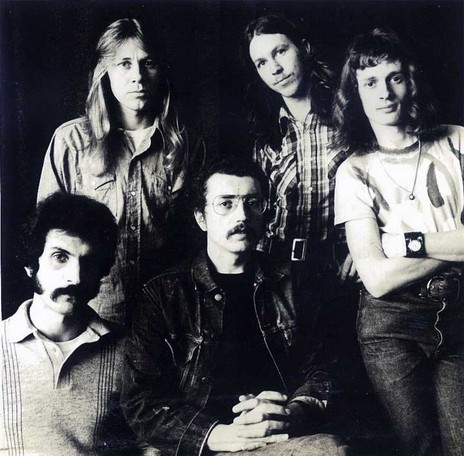

Pritchard had just returned from a stint in Sydney with Retaliation and was seeking like-minded musicians who wanted to play original, experimental, progressive music. Highway featured Pritchard and Lawrie, singer Bruce Sontgen and bassist George Limbidis; second guitarist George Barris joined later. “We mucked around for months and months before performing in public,” Lawrie remembers.

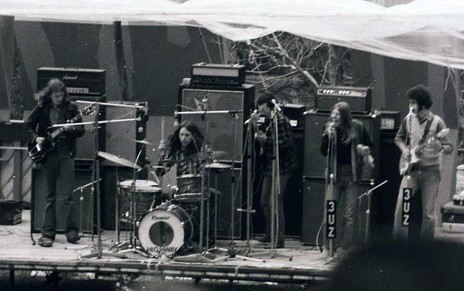

Highway debuted at the Mickey Mouse Club in Taranaki Street in August 1970 and the following week they headlined a midnight concert at the Paramount Theatre, part of the Universities Arts Festival, stealing everyone’s thunder. After months of rehearsal and just two performances, Highway was the hottest band in town. A residency at Lucifer’s followed.

Extremely popular with university audiences, Highway undertook a national tour, the first organised by the newly formed NZ Students Arts Council.

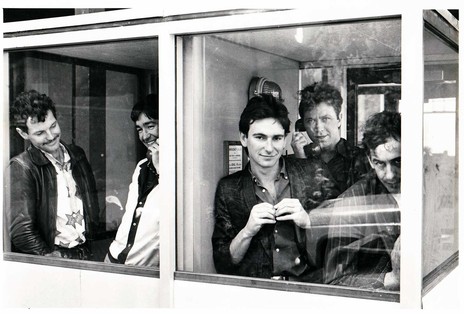

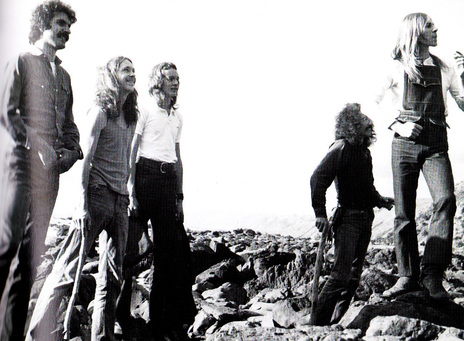

Extremely popular with university audiences, Highway undertook a national tour, the first organised by the newly formed NZ Students Arts Council. They recorded an album for HMV (featuring material never performed on stage) and impressed Daddy Cool leader Ross Wilson, who urged them to try Australia. They arrived in Melbourne in December 1971, immediately coming to the attention of budding entrepreneur Michael Gudinski.

Highway played the major Melbourne venues and the summer music festivals but failed to gain a foothold in Australia. “Michael was great,” says Lawrie. “He was just starting out in the business but he did his best. Billy Thorpe was huge at the time. Daddy Cool was huge. Spectrum were cool, The Chain were cool, and those guys liked us, most Aussie musos seemed to like us but we made no impression on the punters.”

Back in Wellington in mid-1972 Highway disbanded, reformed and disbanded. “We started playing an all-instrumental repertoire, sort of jazz rock, fusion stuff, very jazzy. Audiences didn’t want to know, they were confused. I was a bit confused myself.”

With audience support dwindling, the band went from obscure to full-on commercial. Renaming themselves Danny Douche & The Pelicans, they played nothing but covers – “the Beatles and Stones, we even did ‘The Great Pretender’.”

In 1974 Jim Lawrie was recruited into Midge Marsden’s Country Flyers, enjoying a residency at Wellington’s Royal Tiger Tavern. “I really enjoyed the Country Flyers,” Lawrie says. “I’d never played a lot of that stuff – Johnny Cash, Ry Cooder. We played three nights a week, five dollars a night. Whoopee!

“I’ve got to say that playing with Midge was a musical education, he opened up new music to me. Midge has a wealth of knowledge of different musical styles, not just blues.”

Rockinghorse was Lawrie’s next band. Once a top band, when Lawrie joined Rockinghorse they were reduced to low-key gigs where anyone would hire them. “I thought I was going places when I joined Rockinghorse but I soon realised that they were struggling to play anywhere and we were lucky to make fifty dollars each a week.”

In April 1978 Rockinghorse was playing to a half-filled room at Auckland’s Windsor Castle. Also present, recently returned from Britain, was Lawrie’s old Whangarei mate Hammond Gamble, in the process of reforming Street Talk. The following week Rockinghorse was playing a Palmerston North hotel. “We were staying in the band house – hotel accommodation was too good for musicians – and I noticed these rat poison lids lying around. Within a week I was back in Auckland as a member of Street Talk.”

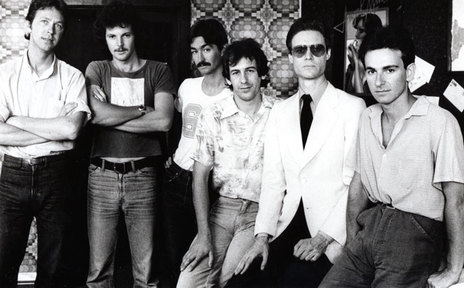

The reformed Street Talk, popular enough in their earlier incarnations, went on to become one of NZ’s top bands. A single, ‘Leavin’ The Country’, produced by Chris Hillman of The Byrds, led to an album produced by legendary Los Angeles hit-maker Kim Fowley.

Lawrie says, “I’d never been in a band so popular. Highway had played to some big audiences and Midge had a staunch Wellington following but Street Talk played to packed houses night after night and we supported Fleetwood Mac and Talking Heads. It was a great time.”

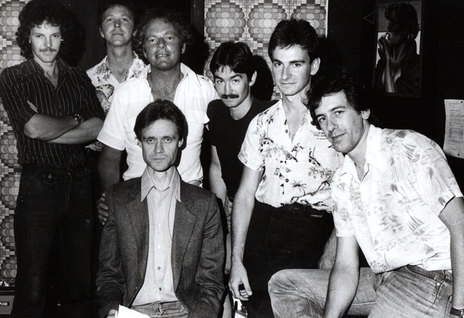

In mid-1980, following a successful national tour promoting the second Street Talk album, Battleground Of Fun, Hammond Gamble surprised all by disbanding one of NZ’s top bands. Jim Lawrie, however, was already moonlighting with another band, resident at Jilly’s nightclub, a band that evolved into Dave McArtney & The Pink Flamingos.

Dave McArtney & The Pink Flamingos was huge, hit singles, two albums, NZ Music Awards, and even larger crowds than Street Talk. Lawrie regards that line–up – McArtney on guitar and vocals, keyboardist Paul Hewson and bassist Paul Woolright – as the best he ever played with.

“I really liked Dave’s songwriting,” Lawrie says, “and he was such a quirky guitarist, a fantastic guitarist, Paul Woolright is just great too and playing with Paul Hewson was a dream come true. What a fantastic musician.”

Jim Lawrie spent two years with the Pink Flamingos, much of it spent in Australia, where the band failed to find an audience, regularly returning to New Zealand to replenish the coffers. The problem was that, despite regular crowds of two and three thousand people, the band was living on per diems, barely covering life’s essentials.

“Australia was tough,” Lawrie remembers. “It was like Highway in a way – musos liked us but the punters stayed away. I guess we could have stuck around, become Australians like Mi-Sex, but we flew back and forth. During one beach resorts tour we were paid four hundred dollars a week, which was fine, but we were grossing ten or twelve thousand a night. Things were so bad, on one occasion I had to dip into my own pocket to pay the band’s airfares, which took ages to get repaid. In Aussie we were living on our bones and I wanted to know why. I started hearing about unpaid bills, our road crew was owed wages. The others thought I was a moaner, stop being a Scotsman!”

The problem lay not with McArtney but with the Flamingos’ manager, no consolation to the underpaid drummer. In 1982, during a return trip to New Zealand, he jumped ship, returning to Wellington where he joined the Dennis O’Brien Band and became in-demand as a session player, including soundtracks for the early Peter Jackson movies.

In the years following, Jim Lawrie was a stalwart of the Wellington scene, playing in resident bands at Chips and Exchequers nightclubs, and on-call for studio and one-off performances. “If there are two people I could single out to thank, it would be Midge and Frankie Stevens, Midge for the music education and Frankie for giving me well-paid gigs during the Xmas season, corporate gigs mostly. Frankie is a thoroughly nice gentleman.”

By the end of the 1990s the work started drying up. “I was no longer trying to make it in the music industry, just trying make a living. Closing in on 50, I no longer wanted to be humping amps.” With a marriage gone belly-up, in 2001 Lawrie shifted to Whangarei, where he survives as a drum tutor at Northland high schools and as an occasional member of the Wallace Brothers Band. He was Billy TK’s drummer of choice for a few years and he has played with Emma Paki and Sharon O’Neill. In 2015 he played drums on Aly Cook’s Alan Jansson-produced album Horseshoe Rodeo Hotel.