AudioCulture

The noisy library of New Zealand music

Te pātaka korihi o ngā puoro o Aotearoa

Ruia and Ranea Aperahama

By the 1990s the brothers were well known throughout the country, and particularly in Māori homes, largely due to their involvement in Southside of Bombay and their Māori language recordings of Bob Marley songs. Their own compositions are a crossover of reggae, Pacific rhythms and world music, often with tight brass arrangements or indigenous expressions that explore what it means to be Māori in a nation still coming to terms with its Treaty of Waitangi-based bicultural heritage.

The multi-instrumentalists have been involved in at least six albums, performed in bands, as a duo and as solo acts. They have won a string of accolades for their services to indigenous music and the use of te reo Māori.

The twins grew up at Rātana Pā, a small community between Whanganui and Bulls, escaping in their late teens from the strict upbringing and brass band sounds of the Rātana Church and movement to explore the wider musical world of Wellington.

Māori was their first language but they quickly became aware of resistance from venues and mainstream radio to play anything that included te reo. They were soon part of the fledgling movement challenging the “ghettoisation” of Māori content and coverage.

While Ruia was at teacher’s training college, Ranea began studying at the School of Music in Wellington, and they quickly forged deep connections with the city’s music scene. They jammed with Māori and Pacific island players, joined Kaihana which had a popular following for a time, and were invited to join Kevin Hodges (aka Kevin Hotu) and others in Southside of Bombay.

Bold as brass

They brought a fatter brass sound to the energetic, reggae-influenced Southside of Bombay with their contribution to the songwriting including ‘What’s the Time Mr Wolf’ and ‘All Across the World’, recordings that helped take the band into the mainstream.

Ruia and Ranea remained with Southside of Bombay for around four years.

Ruia and Ranea remained with Southside of Bombay for around four years, while often joining the brass section of Moana and the Moahunters, for whom Ruia contributed songs.

They quit Southside of Bombay in 1994 when their father became ill, returning to Rātana Pā just as ‘Mr Wolf’ got a second wind when it was included in Lee Tamahori’s 1994 film Once Were Warriors. After a short hiatus they began pursuing collaborative and solo careers.

Their interest in music began earlier than most prodigies. Ruia recalls their mother telling the story of tying a transistor radio to her stomach to settle the energetic twins. “She said we would often butt heads, twist and turn and the songs would settle us both.”

She would also sing hymns and other songs of her generation. “I believe we heard her voice in the womb and ever since that time Ranea and I have had a passion for music.”

The Aperahama twins grew up under the strong influence of the legendary Rātana brass bands, which were a training ground for many New Zealand musicians. By the age of seven they were learning on instruments that were nearly as big as them and soon performing as part of Te Reo o Te Arepa band.

Alongside their tuakana (older brother), Ruia and Ranea joined the mātoro (Rātana fundraising touring party 1979-1981), where they acquired kapa haka and choir skills and learned to read music.

Tough teaching methods

Ruia says the teaching methods of the some of the elders wasn’t always easy. “They were too tough and would smack us. Today they might have ended up in jail if people knew what they were doing. That’s how it was then but the important thing was that we learned.”

Ruia first learnt the clarinet, tenor horn and euphonium, and Ranea learned cornet, tenor horn and guitar. Becoming skilled in multiple instruments ensured they could easily step in if one of the other players couldn’t make it for Sunday service at Te Temepara Tapu o Ihoa (the Rātana Temple).

As he got older Ruia learned the saxophone, which became his passion, and started performing more commercial music with the Rātana big bands at events and functions outside the church and pā.

Ruia soon added keyboard and guitar to his skills and Ranea played guitar for the Rātana big band, later adding trombone and harmonica. Both became members of the Whanganui Garrison Band.

Ranea says musically the brothers generally got on well. “In the process of music making it was whether to use minor key, split harmonies, which instruments to use, composition, arrangements and musicianship.”

Like most siblings though, there were differences of opinion, particularly in how they communicated when it came to political and social topics and what they sang about. Ranea often kept himself to himself. “Ruia was more articulate. He could express himself more clearly. I rank my brother very highly as an orator and linguist. He has a high command of both languages.”

He says there were also perceptions of who should be the younger and who should have seniority in different roles, including Ruia being the speaker for the family. In the early days of Southside of Bombay and when the brothers were collaborating on their first albums he admits he was a little whakamā (shy). “I didn’t say much ... but I was highly observant.”

Sweet inspiration

Ranea says a Māori writers-and-artists hui at Rātana during the 1980s was a profound moment, a turning point in his musical understanding. Many well-known Māori artists of the time gathered, including Hirini Melbourne and Richard Nunns.

A Māori writers-and-artists hui at Rātana during the 1980s was a turning point in musical understanding.

“They performed with a local whānau from the River, the whānau Ponga. ‘Yeah mum, just sing it like you do on the marae’. Piki Ponga then wailed and sang Te Reo o ngā Manu [the language of the birds]. The fusion of taonga puoro, the wailing ‘marae’ voice and the rhythm section in a 6/8 groove just blew my mind. It was game changing,” says Ranea.

Ranea recalls his father Rapine saying to Ruia and himself: “If you overcome the music you will overcome the church. In other words, getting the music out there would be a powerful vehicle of influence.”

Their first foray into recorded music after the exit from Southside Of Bombay was in 1995, when Ruia released the single ‘Ka Tangi te Tītī’, based on the Māori whakataukī (proverb) Ka tangi te Tītī, ka tangi te Kākā, Ka tangi hoki ahau. Tihei mauri ora: “The Tītī is calling, the Kākā is calling, and I wish to call. Behold there is life!”

Ranea, Piripi Ponga and Arahi Haggar on guitar, bass and drums were session musicians for the recording and supported Ruia for several gigs but its success mostly came through airplay on Māori radio.

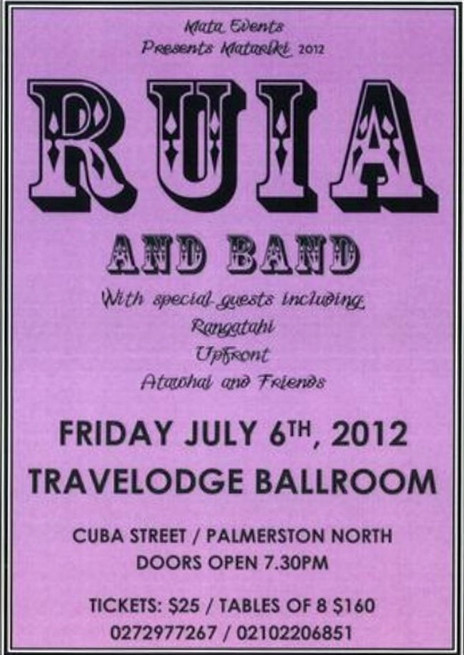

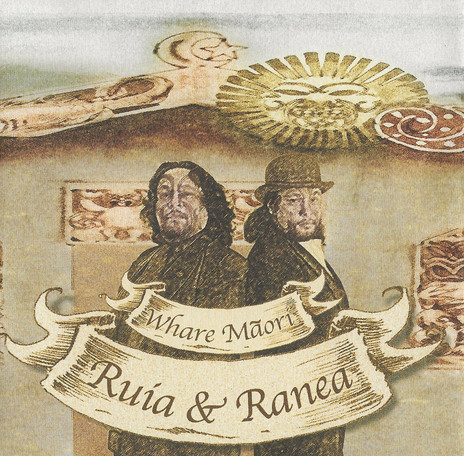

A more collaborative approach was taken five years later when the twins released the Te Māngai Pāho-funded album Whare Māori in late 2000, produced by Flax Wax and released by Tangata Records. Ranea and Ruia shared ideas and vocals, writing five songs each, then polishing them together. Taking a full unit on the road would have been logistically challenging so most gigs were as a duo working with backing tracks.

Keeping memories alive

The album was an expression of their Rātana faith, covering the history of Rātana Pā to inspire themselves, family and wider relations. It was to keep the memories alive and “hold on to the treasures of our parents and grandparents, including the language, our connections and the cultural things we grew up with.”

The name of the album, Whare Māori, comes from the museum at Rātana Pā that housed many historical treasures of the Rātana movement, including documents, photographs and ancestral and tapu (sacred and/or cursed) items.

The bulk of the exhibits however, were the crutches, walking sticks, eyeglasses and other items left behind by those who were healed during the early days of T.W. Rātana’s ministry, which began in November 1918.

The fact that Whare Māori, the museum at Rātana Pā was allowed to fall into disrepair was an ongoing concern for those who wanted to see it preserved for future generations.

Ranea says he and Ruia and others put aside their music and other commitments for a time, worried that evidence of what their parents and grandparents had been involved with was disappearing. “It was frustrating not being in any position to resolve some of these issues; there seemed to be too many challenges to overcome to preserve, restore and protect.”

In the end it was easiest for them to express that history and those concerns in their music. The album Whare Māori received strong support from the Māori radio network and was a finalist in the 2001 Tui Awards.

Bob Marley in te reo

Bob Marley songs and albums sold strongly in New Zealand from the mid-70s and his legendary 1979 concert at Western Springs is seen as an important catalyst for a resurgence of Māori artists blending reggae and Pacific rhythms. The fortunate coincidence of Marley’s birthday falling on Waitangi Day has helped to add mana to the commemorative period.

Seasoned music writer Graham Reid agrees. “Marley was always big among Māori and Polynesians and it doesn't take a great deal of social analysis to guess why. His was a voice for the politically and financially disenfranchised and the socially oppressed. Yet he stood for dignity, spoke with eloquent simplicity (“get up, stand up, stand up for your rights”) and celebrated life and spirituality. His albums were alternately political and party time. He denied racism and loved kids.”

With Bob Marley albums thrashed at parties, social gatherings and Māori households across the country, Ruia and Ranea struck on an idea to translate his compositions to inject some enthusiasm into the uptake of the struggling Māori language.

Ruia says he and Ranea grew up with Bob Marley songs for breakfast, lunch and tea.

Ruia says he and Ranea grew up with Bob Marley songs for breakfast, lunch and tea. Translating his music into te reo was to build a bridge so speaking the Māori language was non-threatening and a novelty. “If Bob Marley can use indigenous music and put it on the map then so can we.”

Ranea says that growing up in the 70s meant there weren’t many role models in terms of an indigenous voice in the messages on the radio and TV. “Bob Marley, as a coloured man, totally connected with us. He sang about the Bible, about revelation ... land loss, racism ... freedom and emancipation ... He was a vehicle for us expressing our own indigeneity.”

Peter Tosh had a similar impact, he says, although he was more militant. “All of this quickly aligned with the spiritual and the Bible and the Treaty for our culture. This was and still is a huge source of inspiration.”

Kohanga reo generation

Ranea sees himself and Ruia as part of “the kōhanga reo generation” and gets great pleasure from seeing their own children carrying on with the language. “That gives me hope ... holding on to the language means they’re better empowered to reconnect with the history and help us to move forward.”

Ruia and Ranea shared the lead vocals behind Waiata of Bob Marley Vol 1 and both were involved in the translation and organising all the vocals over a pre-recorded backing track. It won the brothers a Tui Award in 2001 for Best Māori Language album.

By the time the second album came out Ranea, now with five children, pulled back from “living a musician’s life” to commit to his responsibilities at home.

The success of the first CD meant it was all go for Waiata of Bob Marley Vol 2. Produced by Simon Lynch (Ardijah, D-Faction) at Stebbing Recording Centre in Auckland, it was released in November 2002.

Ruia played acoustic guitar and saxophone and was joined by the subtle harmonies and backing vocal of his wife Erina along with Stephanie Pohe and Vivienne Merito. He says every effort was made to maintain the “wairua” (spirit) of the original recordings and respect for Marley’s music with “the translations ... phrased perfectly to the original melodies [and] ensuring the messages remained the same.”

Because of the licensing agreement with the Marley Estate, there was only approval for a limited release. They quickly sold out and are now “very rare”. The complexity of the recording business and renegotiating with the Marley Estate made it too hard to revisit, says Ranea.

His son Paiheretia Aperahama – a Māori language teacher at Te Wānanga o Aotearoa – uses the albums as a teaching tool. “To know he can recite all the words that myself and his uncle composed, and that he teaches from it, brings great joy and gratitude,” says Ranea.

Paiheretia is a past member of the popular six-piece L40, short for “Latitude -40” the map coordinates for the home of the Rātana-based unit, which performs a blend of R&B, hip hop, neo-soul and reggae.

Ruia hits overdrive

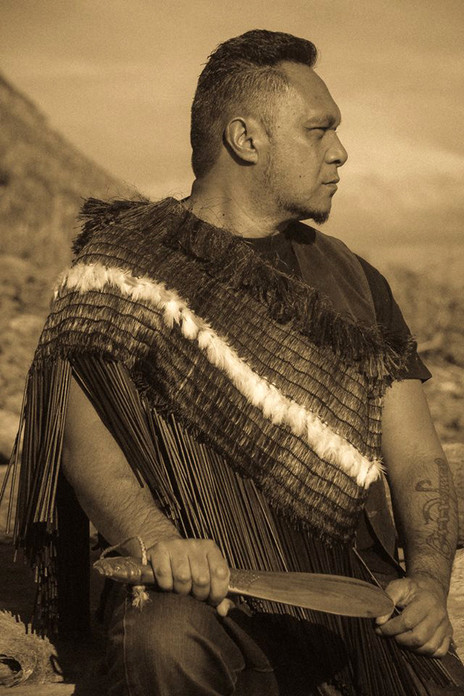

Ruia’s career moved into overdrive with his 2004 debut solo album, Hawaiiki, a predominantly reggae outing “with a pop-jazz tinge” and 11 tracks in te reo.

Hawaiki was recorded at the Far North studio of music icon Billy Kristian who not only produced it but contributed programming, various instruments and co-arranged some tracks. Other session players included former Ardijah member JD, Rob Winch, Carl Doy, the Aperahamas’ older brother Te Kotahitanga (“Manny”), and Ranea. The album was engineered by Doug Jane with some tracks remixed in Wellington by Jeremy Geor, who produced the Whare Māori album. It was mastered by Simon Lynch at Stebbings in Auckland.

Released in January 2004, Hawaiki won a Tui Award the same year Ruia won the Apra Maioha Māori songwriter of the year award for a track from that album, E Tai. Ruia won the Apra Maioha Award again in April 2008 with ‘Rere Reta Rere Reta’ from his album 12:24 or Tekau Mā Rua: Rua Tekau Mā Whā.

It was released in May 2009 in time for New Zealand Music Month with a double billing alongside Moana and the Tribe “to give more emphasis to Māori music”. The producer was Chris Macro, whose past credits included Katchafire, Dubious Bros and Whirimako Black. Again, all tracks were sung in te reo with reggae rhythms, traditional vocal chants, programmed beats and live instruments.

Ruia played keyboards, saxophone and acoustic guitar and musical director Craig Denham doubled on keyboards, with Tobias Wright on bass, Tipene Rogers on guitar and Richie Campbell on drums. Ranea was on trombone, harmonica and vocals, older brother Manny on flugelhorn and vocals, with Chris Macro on drum programming, keyboards and sequencing. Guest vocalist Whirimako Black was on the track ‘Kēkeke kooo’.

Jamaican pilgrimage

After celebrating the launch, Ruia travelled to Jamaica to film a documentary for Māori Television about its music and musical ties with New Zealand, which he saw as a kind of “spiritual pilgrimage”. When he returned after a 20-hour flight, his wife Erina was waiting for him at the airport with a New Zealand Music Award for best Māori album.

Ruia had immersed himself in a punishing schedule of projects, studies, TV hosting, recording, songwriting and composition. He contributed songs to the Moana and the Moahunters albums Tahi (1993), Rua 1998) and Toru (2003) and toured with them in Europe.

He spent time in Japan in 2007, pursuing aspects of the culture and heritage there that were forged by T W Rātana in 1924 when he partnered with Japanese Bishop Juji Nakada after the ship returning from their London tour – with a 40-strong Rātana concert party aboard – was stranded in Tokyo.

While staying at Bishop Nakada’s Bible School and Music Academy the two men became friends. When Nakada came out to New Zealand for the opening of the Rātana Temple in 1927, he brought with him the written music for many of the original songs still sung by the Rātana bands and choirs.

In late 2009 Ruia was hosting the Nine to Noon show on Radio Waatea 603AM, studying for a post-graduate diploma in Business (Māori Development) Studies at University of Auckland, and working as an associate researcher at its Mira Szászy Research Centre for Māori and Pacific Economic Development.

All the while there seemed to be session work, artwork for publications, teaching music part time at Te Wharekura o Hoani Waititi marae in West Auckland, efforts to restore heritage at Rātana Pā, and of course touring.

Ruia was involved in the first season of TV SERIES ‘SONGS FROM THE INSIDE’.

The invitations to perform included a tour with Ardijah in 2011 with a set from his 12:24 album before joining them as part of their show.

Ruia was involved in the first season of Songs From The Inside, the 2012-2015 Māori Television series following top Aotearoa artists – including Anika Moa, Warren Maxwell and Maisey Rika – as they taught songwriting to prison inmates. CDs of the music were later produced and released.

The accolades kept coming. Ruia became an honorary recipient of the Toi Iho Māori-made trademark that recognises individuals of Māori descent, and guarantees the high quality of their product, including his own CDs. He received an Arts Foundation Laureate Award in 2012, recognising his prominence as an artist and outstanding potential for future growth.

Facing the demons

Behind the scenes, however, few would have known that the brothers were facing deep personal challenges based around insecurity and the growing expectations placed on them. From around 2008 Ruia began to open up about the personal struggles he’d been facing for a number of years, including depression, addiction and ultimately a failed suicide attempt that saw him hospitalised.

He spoke to Radio New Zealand’s Te Ahi Kaa programme about childhood abuse and the deep pain he masked through alcohol and drugs resulting in several periods in rehab dating back to 2004. This had been exacerbated by trying to live up to the constant career expectations. In a further conversation with Te Ahi Kaa in October 2014, Ruia spoke of his slow and painful road to recovery and facing up to what had happened so he could deal with the anger.

The journey included an epiphany, that in order to escape the “dark and ugly places” he needed to forgive and even love himself and forgive and love others without expecting anything in return. “I was living on auto-pilot, not taking responsibility and running from the consequences of my actions.”

He realised “no one else can make me happy or sad except myself” and as a result began to see himself in a new way and “relate to other people in a different light”.

Brother Ranea also had to face some home truths, having faced similar challenges of abuse and violence as a young boy. “You don’t realise how much these things impact on your life [particularly] when you are going through the phase where everyone is saying ‘you’re the man, you must have your shit together.’”

While it’s great to know you can inspire people, he says “deep down there are still these ghosts that can eat you up inside”.

He learnt a lot from what his brother Ruia went through, including the need to address “the demons and things in life that keep you so preoccupied,” questioning what was really important in his life. He says many musicians, artists and actors, including young people, don’t manage fame and expectations well, particularly when they get used up and spat out at the other end. “If I knew then what I know now my approach would be very different.”

Ranea says putting yourself out there as an artist is not an easy thing to do. This was something he struggled with in Southside of Bombay, preferring a safe place in the background. “I didn’t really like being in the public eye, opening myself to the world and becoming vulnerable.”

That, says Ranea, requires a certain kind of inner strength “when you hear criticism both positive and negative – some of the criticisms can be soul destroying.”

Ranea’s solo outing

Although Ranea had co-written a number of songs with Southside of Bombay and collaborated with Ruia on several albums, it wasn’t until 2015 that he delivered his own solo album that saw him recognised as a major talent.

His debut, Tihei Mauri Ora, a collection of original compositions written over 20 years celebrating the gift of life was launched at Rātana Pā in January 2015.

Ranea told Waatea news that former Southside of Bombay bandmate Maaka McGregor (Maaka Phat), engineer and producer of the album, helped him to overcome his shyness to release songs under his own name. Maaka encouraged him, saying: “Kia kaha bro, it's a part of having a gift and sharing it with the world.”

This was a chance to stand on his own feet, “expressing myself and taking responsibility for it”. The songs on the album were to rejuvenate and invigorate his spirit, “to encourage it to flitter beyond the clouds of despair – to feel and connect with the breath of my deepest consciousness.”

The album embraced proverbs from different tribal areas that spoke of a common theme, a call to unity; for people to be aware of social issues and awaken to Māori language and culture.

“Tihei Mauri Ora is the calling of our consciousness to not just go along and be ‘baa baa black sheep’ ... but to be aware of what's actually happening for us and our future generations – our children and our grandchildren.”

Quoting the essence of the title track, Ranea says, “Life is a gift, my heart beats with the earth, my breath beats with the heavens, your breath my breath, a heart that is firmly placed as the ancients of heaven, oi! My heart! The sneeze of life into the world of light!”

An economic language

By May 2015, title track ‘Tihei Mauri Ora’ had tipped Stan Walker’s ‘Aotearoa’ off the top of the Te Reo Māori top 20 airplay chart and Ranea was nominated for seven Waiata Māori Music awards. The album claimed four finalist spots: Best Traditional Māori Album, Best Māori Pop Album, Best Māori Hip Hop/Rap/RnB Album, and Best Māori/Urban Roots/Reggae Album.

More music industry support for Māori language music was needed, “not only as a cultural thing, but as an economic language” – Ranea

During the release of the album, Ranea expressed his concern for the survival of the language, saying there was a need for more industry support for Māori language music in the mainstream, “not only as a cultural thing, but as an economic language”.

The irony of what unfolded at the November 2015 Vodafone 50 years of New Zealand Music celebration was not lost on him. The awards, the industry’s biggest event, were televised live by Mediaworks on TV3. While Māori artists including Six60, Marlon Williams and TrinityRoots were shown receiving their awards, the Māori language category was not.

Although aware of the time restrictions, Ranea, when called up for Best Māori Recording for Tihei Mauri Ora, decided – marae-style – to honour his father as well as All Black legend Jonah Lomu who had passed away only days earlier.

“Our father loved and respected Jonah Lomu, so I said I wanted to honour them both by doing the Ngāti Toa haka that is well known throughout this nation – and that’s when everyone in the building who knew it stood up.”

The TV cameras immediately cut away to announcers giving a summary of other events and when they came back Ranea had already received the award. This further fuelled an ongoing debate about “white-listing” of music containing te reo lyrics and the “ghettoisation” of Māori content and coverage, confined to dedicated Māori television and radio stations, depriving all New Zealanders of a vital part of our nation's culture.

A complaint was laid, with Māori expressing frustration that this snubbing was commonplace. During a meeting with musicians and industry representatives it was agreed that in future the industry would try to do better.

For Ranea though, the awards kept coming. He won the Radio Airplay Song Of The Year award by a Māori Artist in Te Reo Māori for the title track from Tihei Mauri Ora at the 2016 Waiata Māori Music Awards.

The award, presented by National Māori Radio Network chairman Willie Jackson, was for the Māori language song which achieved the most airplay on Māori radio stations that year. At the end of the evening an impromptu performance of ‘What’s the Time Mr Wolf’ by Ranea, with Hamilton band Rootz Konekt, received a standing ovation.

Ranea, no longer taking a backseat, having worked through his issues with fame and family, and with a strong platform of his own, believes the growing acceptance of the Māori language is a sign of a maturing “treaty nation”. He says that’s partly due to the fact the younger generations have been more exposed to the language than his generation and that of his father.

How far have we come?

“When we look at Dave Dobbyn’s Māori version of ‘Welcome Home’ ... when I see the Finn brothers doing things like that, I see us working in the spirit of the treaty and upholding our unique language, which belongs to us.”

Of course, he says, that’s an unfolding journey which the music industry needs to take greater responsibility for. “We’re not there yet but we’re a lot closer than we were 50 years ago with Howard Morrison and Tui Teka and the attitudes that were around then.”

“I WANT TO ENCOURAGE MĀORI AND PACIFIC ISLANDERS TO CREATE A UNIQUE SOUND FOR THE SOUTH PACIFIC” – RUIa

During the promotion of Tihei Mauri Ora Ranea found many industry people showing a renewed interest in Māori music; he was surprised they were just discovering Whare Māori, the album he and Ruia first collaborated on and which he believes is a benchmark.

There was some talk of a new album in 2018 but that was put on hold for several reasons: the difficulty of keeping a band together, the cost of touring and the changing economics of the music business.

“There’s so much work for so little return,” the digital world has changed so much (“everything’s free online”) and besides, he has another gig as Māori writer at Te Papa working on exhibitions with the taonga there.

The last taonga he recorded is the song and video clip ‘Te Paki o Matariki’ about the Māori New Year and “celebrating our unique position, where we are located in the world, which shouldn’t be underestimated.”

Like Ranea, Ruia continues to be a strong supporter of the opportunities for Māori music that have opened up through growth in Māori television and iwi radio. “I want to encourage Māori and Pacific Islanders to start looking at creating a unique sound for the South Pacific,” he says, with the ultimate goal of taking those hā-Kiwa (breath of Kiwa) musical forms to the world.

Visit our sister site

NZ On ScreenMade with funding from

NZ On Air