The family spent a lot of time with their grandfather, while their Ngāti Porou mother, Hera Te Mirowai, worked long hours at the Ruatoria telephone exchange. “We only had a radio, we didn’t have power when I grew up, so we didn’t have TV.”

But music has always been part of his life, he said on RNZ’s Musical Chairs in 2002. His brothers and sisters enjoyed performing, and Apanui began to pick up the guitar (finding the chords his brothers played were often not correct). At primary school, music centred around action songs, and there were also hymns in church. Apanui always preferred the guitar, and began writing his own songs. The only Māori-language song he remembers hearing at school was ‘E te Hokowhitu-a-Tu’, written to the melody of Glenn Miller’s ‘In the Mood’.

From an early age Apanui was committed to New Zealand music. He told Saw, “I began this argument with my brothers about New Zealand music being as good as anywhere else in the world.”

As a teenager Apanui boarded at St Stephen’s College at Bombay, South Auckland; it was an experience that was sometimes “brutal”. But while there, his music was encouraged by a teacher, and he decided he wanted to write Māori music.

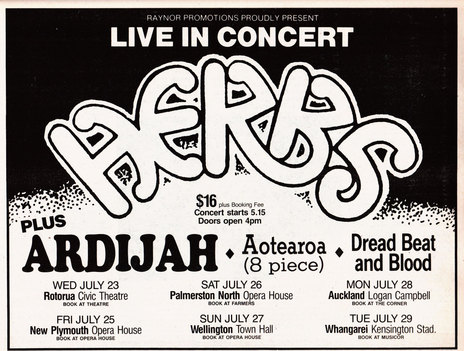

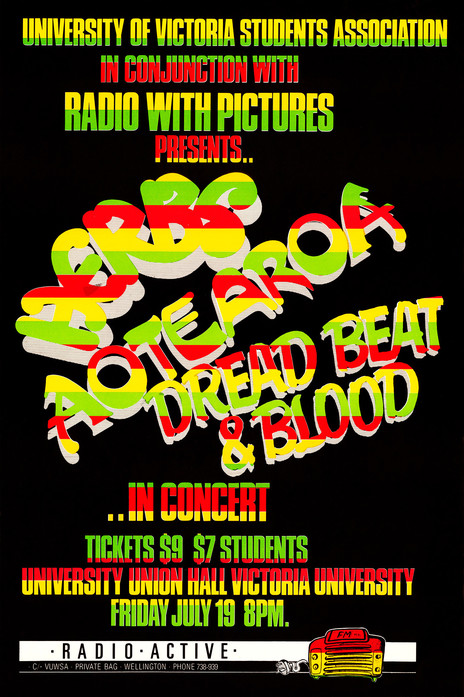

Another key moment during high school was a visit to Bastion Point in 1977, when he was in the third form. “I knew the place was special,” he told Saw, “though I wasn’t particularly aware at the time.” This experience was intensified when he saw his first New Zealand band, Herbs, shortly after their seminal Whats’ Be Happen? album.

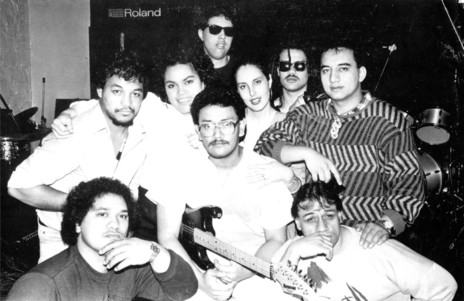

“Herbs were the band that really got me thinking,” he told Saw. “When I left school I wanted to start up a band that sang in te reo Māori. After that first Herbs gig at university in 1982, it was just after Toni Fonoti had left the band, and I was a bit disappointed, because he was the man for me. I loved his songwriting. Willie Hona had become the leader of the band … I was blown away and inspired to start my own band. That was really the event that kickstarted Aotearoa.”

Apanui’s opportunity to both start a band and begin writing Māori music came when he enrolled at Victoria University of Wellington to study law. “While I was at boarding school I worked hard as I didn’t want to waste [his mother’s] money. But at university I missed classes and played guitar.”

The meeting place for Māori students was the university marae, Te Herenga Waka, where Apanui met another law student, Joe Williams (Ngati Pūkenga, Waitaha and Tapuika). The journey began to form Aotearoa, with its commitment to original songs in te reo Māori. (See accompanying story, “Aotearoa: He Waiata Mo Te Iwi”.)

Aotearoa is best known for the waiata ‘Maranga Ake Ai’, released in 1985.

Aotearoa is best known for the waiata ‘Maranga Ake Ai’, released in 1985 on Jayrem Records. The song was a political protest, a kaupapa Māori driven message that expressed the need for Māori self-determination and empowerment against colonisation and its detrimental effects. It utilised a solid four-on-the-floor reggae beat that rhythmically helped to push the lyrics out. For so many young Māori this waiata has become an anthem against oppression with a message: Māori people, gotta wake up, gotta take up the cause.

‘Maranga Ake Ai’ was composed over a period of three years. Apanui recalls the time when he was hanging out playing guitar at Te Herenga Waka, when Williams turned up one day with the first verse and melody. They were joined by Kararaina Rangihau and Maru Karatea who added their distinctive harmonising and backing, most clearly heard in the a capella introduction.

Apanui recognised the waiata had something special and needed to be recorded. ‘Maranga Ake Ai’ and ‘Haruru Mai’ were both recorded at Marmalade studios in 1984 with the help of Denys Mason as producer and Ian Morris as engineer. They were joined by drummer Tim Robinson (of the Eelman scene), who played that discernible reggae beat.

In E-Tangata, Apanui reflects on this time: “After listening back to the rhythm track for ‘Maranga Ake Ai’, we both knew it was going to be a special song. It just sounded so great. I played that song probably thousands of times to people before we got the release deal with Jayrem Records. When it came out it was already widely known in te ao Māori”.

‘Maranga Ake Ai’ was released at a time in the 1980s when Māori renaissance was peaking with the establishment of Kohanga Reo, Kura Kaupapa Māori, and the Māori language claim to the Waitangi Tribunal. Apanui recalls, “I remember thinking at that time that we could achieve anything that we wanted. It was an amazing time to be involved. I know the Māori language claim led to the establishment of Te Taura Whiri [the Māori Language Commission] … there just didn’t seem to be anything that we couldn’t do.”

Considering the revitalisation of te reo Māori, I asked Apanui why ‘Maranga Ake Ai’ was bilingual. “We wanted people to understand the words, that was the main thing, we were aware that a vast amount of Māori didn’t speak Māori so it was about getting that message across.”

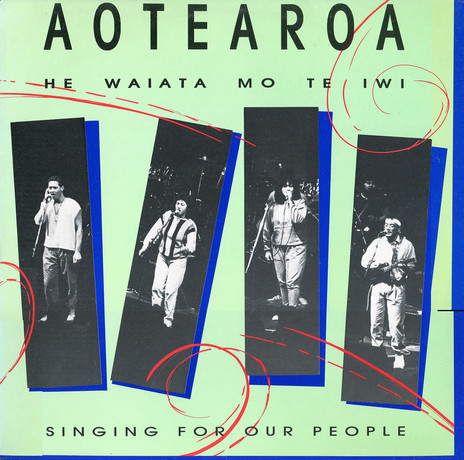

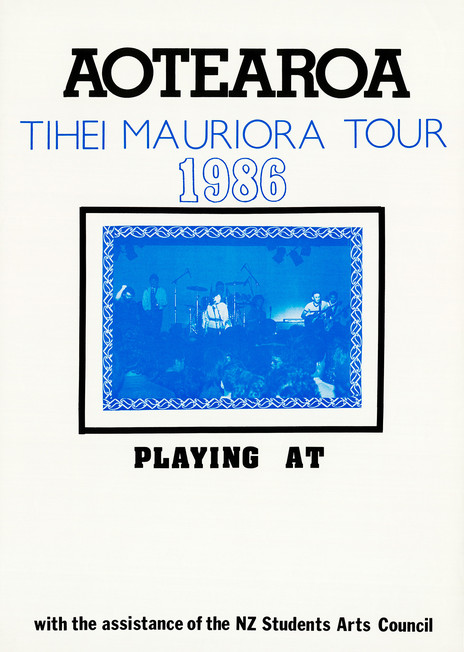

Aotearoa’s debut album Tihei Mauriora appeared in 1986 shortly after the band took part in a groundbreaking national tour, organised by Hugh Lynn, that also featured Herbs, Ardijah, and Dread, Beat and Blood. A second album, He Waiata Mo Te Iwi, followed in 1987. (By that stage Williams had left; he went on to become Justice Joe Williams, appointed to the Supreme Court in 2019.)

Looking back at Aotearoa with Trevor Reekie of NZ Musician in 2011, Apanui said, “I had a very clear kaupapa for the band and that revolved around te reo Māori and communicating pride in being Māori. I also wanted to move towards incorporating taonga puoro and waiata tahito [traditional song poetry] into our music, but culturally the band wasn’t ready for it. The band began to move towards its potential around 1987/88 and by the time of our last gig at Otago University in 1989, I felt Aotearoa had become a very strong live act.”

“I had a very clear kaupapa for the band and that revolved around te reo Māori and communicating pride in being Māori.”

After the demise of Aotearoa, Ngahiwi Apanui released two solo albums with Jayrem Records. The first was Te Hono Ki Te Kainga (The Link With The Homeland) in 1989, which featured the musicianship of Elliot Fuimaono on bass, Malcolm Ratapu on blues harp, flute and backing vocals, and Kevin Hodges on saxophone. Apanui performed as a multi-instrumentalist on the album, playing guitar, keyboard, percussion and singing lead vocals.

The second album, titled E Tau Nei – featuring 10 tracks, all sung entirely in te reo Māori – was released in 2002. It was produced by Wai Music: Maaka McGregor (who, as a 15 year-old, had played percussion with Aotearoa in the mid-80s) and Mina Ripia. E Tau Nei won the Tui for best Māori album, and the inaugural APRA Maioha award, for the song ‘Wharikihia’.

In an interview with Sounz in 2019, Apanui explains his vision for contemporary te reo Māori music, saying that it requires an edge, something original – and more importantly, a kaupapa. He says Alien Weaponry demonstrates how heavy metal can be a vehicle to engage and connect with Māori language, just like when Aotearoa used reggae as a musical genre to facilitate their message.

Having invested a good deal of his time in kaupapa Māori music and education, Apanui turned his attention to broadcasting. For eight years he was the manager of Radio Ngāti Porou in Ruatoria, a position he upheld to provide an essential platform to revitalise Māori language and culture. While there he produced the Manu Waiata compilations.

Managing the station provided a way of broadcasting and communication dedicated to the iwi, hapū and whānau of Ngāti Porou. During his years as CEO, Apanui was proud to increase the revenue of the radio station but says “the most rewarding aspect of the role was working with a great board and some wonderful people for a greater cause.”

Apanui went on to establish the Māori Media Network which is the advertising sales agency for Māori Radio. It was the successful culmination of four years of consultation and planning with Māori radio stations all over the country.

Working in education has been a real passion for him. He started in tertiary education in 2003 and finished nearly 10 years later. His fervour about education is evident in his conversation with E-Tangata: “I had this belief in education, because education had shaped my life in a positive way ... educational success and cultural identity for Māori go hand-in-hand.”

Apanui attributes his passion for education to his mother who, while he was growing up in Te Araroa, instilled this at a young age. As a solo parent she worked tirelessly to pay for him and his three brothers to attend St Stephen’s School, and for his sisters to attend Queen Victoria School.

Music making continued in the 2000s, fitting it around his family and work commitments.

Music making continued in the 2000s, fitting it around his family and work commitments. In 2011 a third solo album appeared, Matariki. Making it was deeply satisfying. “The album was about re-establishing my musical identity,” he told Reekie, “and with the assistance of my partner Hinerangi Barr, we wrote, planned, and managed the project and produced something that reflects me musically, that belongs to us and our whānau. That partnership is something I value and I look back on the experience with much pride.”

In 2015 Apanui became CEO of Te Taura Whiri i te reo Māori – the Māori Language Commission, based in Wellington. He says his challenge is to win the hearts and minds for all people in Aotearoa/New Zealand to become engaged in learning te reo Māori. He explained his approach in E-Tangata: “It’s about getting more people into te whare o te reo Māori [the house of the Māori language]. All of New Zealand are our manuhiri. We need to welcome them into the house, look to understand their te reo journey, and put support in place to help them succeed.”

Having always been a champion for te reo Māori language revitalisation, he believes this kaupapa is one that requires the engagement of all New Zealanders in order to be fully realised and for the nation to be truly bilingual. However, he is circumspect about realistic timeframes and says that this may not be something that will be accomplished in his lifetime.

“It’s an aspirational goal in a long game. We envision a nation that values te reo Māori. A nation that’s engaged in the revitalisation of te reo Māori. And a nation that speaks te reo Māori.”

He is passionate about how Māori people can find kaupapa Māori-driven solutions towards the revitalisation of Māori language, through understanding the digital world and using technologies such as apps, audio books, PCs, tablets, and smartphones. “We need to learn how to use digital tools to engage and teach people.”

As an advocate for how kura kaupapa and kōhanga reo can be a vital part in the successful revitalisation of te reo Māori and for rangatahi, Apanui affirms his belief: “Kura kaupapa is a proven, real-life example ... and the value of this has been proven by kura kaupapa. The evidence shows that when you look after a Māori student’s identity, reinforce and value it, and engage whānau with the kura, they will do well.”

One thing I sensed when talking with Ngahiwi Apanui for AudioCulture was his passion for justice and being an agent of change for his people. I asked him if he had any last words to add to our conversation. “Music is a tremendous creative expression,” he says, “that has the power to call out racism and injustice without causing more pain ... like Bob Marley sings ... ‘When the music hits, you feel no pain.’”

--

Read more: Aotearoa: He Waiata Mo Te Iwi

Read more: Music from the Long White Cloud

Read more: A E I O U – Milestones in Maori Music