It was a steep learning curve for Binder, who had little previous experience in music. “I was only in the band at the beginning because no one else wanted to get on the mic and sing and jump around. But learning to play with people who were so much better than me, forced me to get better quickly. I just wanted to be the lead singer, but Chris said – ‘no we need two guitars, we need more density on some of the songs’. I’d only had one guitar lesson when I was 15, so Chris taught me heaps. It helped so much in the end, because it later influenced the way I wrote songs.”

After a few gigs around the city, they did an early recording session at Progressive Studios of their early “post-punky, gothy” tracks and van de Geer immediately found himself taken by the recording environment. (He later enrolled at School of Audio Engineering/SAE). Yet Casey eventually found himself too busy with his other bands and quit the group. By this stage, van de Geer and Binder were living together at a flat on Sentinel Rd, and van de Geer recalls it wasn’t hard to find replacements.

“Through the scene someone suggested Jules Barnett. He was great because quite a bit of the stuff that we were doing was quite intricate, involved material and Jules loved to play technically tricky stuff. There was a really creative and supportive scene for meeting other musicians at the time. We were friends with some key people who lived up the road from us on Curran St – Shirley [Charles now Simpson] and Mark Anderson-Jones from Freak Power; Matthew Heine and Lance [Strickland] from Albino Slug/S.P.U.D.; and also Andrew Moore (author of Yeah Bo fanzine). Our two flats partied every weekend and went to a lot of gigs. Paul got a proper job and announced he was leaving. By then we were also flatting with Barbara [Morgan] and she was already playing with Fatal Jelly Space, so we said ‘hey, we need a bass player’ and she was totally into it.”

The young group were intent on not sounding like any other group.

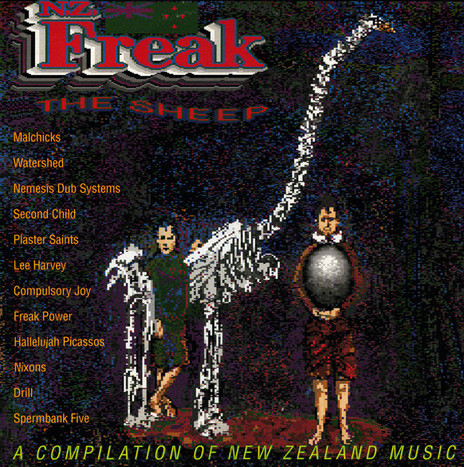

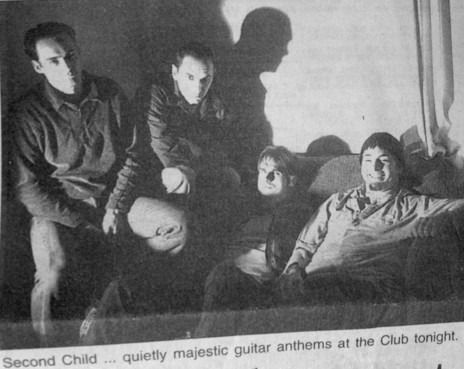

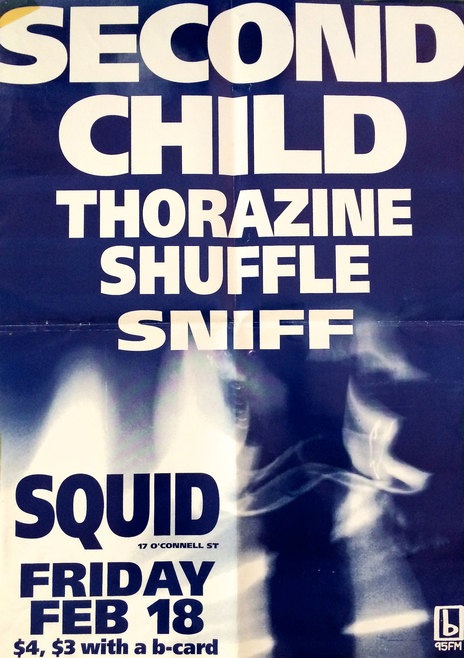

Auckland’s live scene was thriving over this period and the band had up to this point often played in front of a couple of hundred people at the University Cafe, as well as doing all-ages gigs at the Grey Lynn and Parnell Library Halls, the Ponsonby Community Centre. They had moved onto shows at licensed venues like the Beach Road Hotel, Rising Sun Hotel and the Dog’s Bollocks. During weekend downtime they recorded three new demos on the 8-track at bFM with Matthew Heine, who was the production engineer there. One of these, ‘Flock Before Me’, became a bFM No.1. By 1989, they’d booked into The Lab with Heine to record seven further songs. They found a strong supporter in Lisa Van Der Aarde who hosted the Freak The Sheep show on bFM and was putting together a compilation through Flying Nun, which gave Second Child their first official release in 1991 (‘Right Up’ appeared on Side A of the cassette).

Another supporter of the band was music writer Kirk Gee, who became their de facto manager over this period. They’d initially been in discussions with New Plymouth-based label, Ima Hitt, when Gee introduced them to Murray Cammick – Rip It Up editor and Southside label boss, who had just started a rock label, Wildside. Their mini-album, Magnet (1991), appeared on Cammick’s label soon after.

The young group were intent on not sounding like any other group, and for this reason van de Geer eschewed power chords in favour of ever-changing riffs that spiralled around Morgan’s busy basslines and Barnett’s wild, skittering drum playing. Their songs were held together in part by the strength of Binder’s voice, which yowled over the top, drawing melody from the chaos. Though van de Geer does believe they got a bit carried away: “We were just stubborn little shits really. We’d say – ‘we’ve got this great chorus, but we’re only going to do it once and go somewhere else.’ To our own detriment probably. We weren’t honing them as songs in a traditional sense, it was more about a journey of energy.”

Music writers and DJs lapped it up and, in addition to Lisa Van Der Aarde, fellow BFM DJ Simon Coffey became an early supporter of the group, along with Jonathan King, who edited indie magazine Stamp and went on to direct music videos for the band as well as doing cover design work during their Slinky period. Morgan left soon after the release of Magnet due to her commitments with Fatal Jelly Space and was replaced by Theo Jackson (from funk-metal group, Deep Sea Racing Mullets).

Music writers and DJs lapped it up.

Through this period the band supported The Rollins Band for two nights at Auckland’s legendary Gluepot venue, as well as playing with Bailter Space (a fave New Zealand act of van de Geer and Binder’s at the time) at the same venue and US post hardcore band Fugazi at the Powerstation. In 1992, along with The 3Ds, they received the much-coveted spot supporting Nirvana at the Logan Campbell Centre. This gave them the opportunity to watch the grunge legends soundcheck from side of stage (though the US trio were burnt out by endless touring and didn’t stop to chat).

Binder recalls that Jackson’s arrival sparked a new phase of the group, especially once Barnett parted ways with the band the following year:

“Theo was actually a huge fan of Second Child and came to all of our gigs. That’s when we started creating more simplified song structures and laying down a strong foundation with drums and bass. Our songs were very long before that. People would say, ‘it’s good, but I don’t hear a hook.’ Theo also turned me on to Bob Dylan quite a bit. We were all changing what we were listening to quite a bit around that time. But we were still into Afghan Whigs, along with some of the SST bands, Sonic Youth, Pixies and REM. We also listened to Hüsker Dü quite a bit – I’m still a big fan of Bob Mould. Songs with melody that still had some heavy guitar and still retained a nice edge to the music.

“It was definitely becoming a bit more focused with Chris and I sitting down to write a song then bringing it to the band. Before that, we’d write songs with jams and would spend three months on one song! We could work a lot faster by writing together as a duo first. Then Theo would get a really good groove going that we could put the song on top of.”

Second Child kept up their momentum by releasing a follow-up single, ‘Hold Back’, in 1993. They still had no drummer so Casey re-joined them for a short period and filled in for this session. Isaac Tucker recorded the three tracks on Second Child’s next single ‘Crumble’ (released in 1995) and the track displayed how much the band had changed. Recording it at York Street with Malcolm Welsford meant they now had the big sound of a modern rock band and Binder’s melodic singing in the chorus provided the perfect counterpoint – meaning the song came across as both heavy and supremely catchy.

“It was four people going in the same direction.”

The drum seat was finally taken over by Ben Lythberg from the hardcore group Balance, which Binder found was the perfect fit. “Ben was a few years younger than us, into faster punkier US stuff and a powerful drummer. He was also a fan of the band and regularly came to our shows. He was just what we needed and leapt at the chance to do some different music. So it was four people going in the same direction for that period of time.”

The band were preparing to enter The Lab (where Chris was now working as an engineer) to record a new single, when Binder and van de Geer instead decided to push themselves to complete a whole album. This meant a flurry of songwriting had to take place in the studio, while van de Geer used his growing studio skills to record, mix and produce the sessions (with Binder acting as co-producer).

Their new tracks gave them a more polished sound, but there wasn’t an obvious path beyond student radio since Hauraki was the only commercial station that focused on rock at the time (in the years before Channel Z and The Rock). This left van de Geer feeling like they were a little stranded: “We were definitely stuck in between. Especially because our rock wasn’t straight-ahead dumb rock. There was always a lot of layers to it, musically and theme-wise. It was a little more complicated than what you’d put on purely as fun party music.”

On the upside, their music videos continued to gain high rotate on Max TV (where they found a champion in VJ Zane Lowe) and even regular airings on the music video shows on the mainstream channels, which Binder traces partly to a canny decision by director Jonathan King: “We had a whole run of videos with Shortland Street actors. John Leigh in ‘Disappear’. Joel Tobeck in ‘Desire You’. Angela Bloomfield in ‘Prove You Wrong’. It was a who’s who of Shortland Street.”

The album, Slinky (1996), showed the group’s mature sound: acoustic guitars provided the basis for some of the tracks and Binder’s melancholy vocals were pushed out to the forefront. They played some more high-profile support slots over this period (The Jesus and Mary Chain, and Hunters & Collectors) and also played at that year’s Big Day Out festival and were featured on a compilation CD that coincided with the 1996 Music Awards (despite not being nominated themselves).

They recorded a new run of demos, but progress slowed when Lythberg announced that he was moving to the US. After Lythbergs’s departure, Andrew Maclaren, the drummer from Stellar*, filled in on ‘Slip Away’ which was used as a B-side for ‘Disappear’. (The also featured Bic Runga on backing vocals: she had been recording demos engineered by van de Geer.) At this time, van de Geer was increasingly busy in the studio working with a diverse roster of acts that included Garageland, Greg Johnson, Pash, Muckhole, Eye TV and the Strawpeople: “My whole engineering and production career was just taking off. I remember being at The Lab one night and I could hear Second Child rehearsing without me in our practice space behind Kurtz Lounge, because I couldn’t make it – I had to mix a track. At that point I realised my focus had shifted too far. Damien was still coming up with new songs, but things had started to break away.”

Binder found the final decision to end the group came without any animosity.

Binder found the final decision to end the group came without any animosity: “We had our third drummer by then, so that was an on-going problem. Ben had left and he’d really propelled the band quite amazingly – there was a really great energy with him and we just couldn’t replicate that ... Theo wanted to do some other stuff and I was doing my own writing. We were all going different directions musically. I think I just rang Chris up one day and said, ‘maybe we should just leave it’ … It had become a strain because we were also managing the band ourselves. Trying to get gigs, trying to organise rehearsals. When you have the main two people in the band splitting away and doing other things then it’s naturally going to reach a conclusion.”

After the demise of Second Child, Damien Binder took a little while to consider his options: “I had a whole bunch of songs that I started recording with Second Child. I sat on these songs for a while and wondered if I had the guts to go it alone. That’s when I started working with Bob Shepherd, who encouraged me to write. He said, ‘I’ll produce your record’ – and it went very well. The thing is, when you’re a band of four people together then you’re a gang, but when you’re on your own you realise you have to actually get your own band together and make it sound good. Suddenly you’re not just thinking about your part, you’re thinking about what the bass is doing, what the drums are doing. You grow up real quick.”

Binder continued to work with Shepherd on all four of his subsequent albums. Binder’s self-titled solo album (2000) led to Jonathan King receiving best music video at that year’s awards for the track/video ‘Good As Gone’. The title track of his next album, Til Now (2003), was a finalist at the APRA Silver Scroll Awards and he spent the intervening years touring in support of well-respected acts like Ani DiFranco and David Gray (the latter put him in front of audiences of up to 4000 people).

Binder eventually decided to move to Australia and continue his solo career there. “It just didn’t feel like I was going anywhere. I didn’t feel like I was going to break into the territory of the Bic Rungas and Dave Dobbyns, so I just packed up and went to see if I could forge something new somewhere else with a new audience. I only planned to go for a little while, but I ended up meeting my future wife and so I stayed. I did another record in 2009 [While The Wind’s At Your Back] and then one in 2016 [A New World]. The output is a bit slower, but I’m still playing a lot over there. Shortland Street is still playing my solo records, including my new one which is great. [It's] thanks to Graham Bollard who programmes their music, he likes my stuff and has been a strong supporter. I’ve recently just written a bunch of songs which I’m really happy with and have just kicked off the recording of a new album. It’ll be good to follow up my last one more quickly this time.”

Chris van de Geer has had an even busier life in the music industry post-Second Child. After a short period he joined the group Stellar* which took him out of the studio for a couple of years. “Around 2000, I came back between albums and did a Tim Finn record and a few other projects. Then we had a break after the second Stellar* album, so I got fully back into engineering and producing records. In 2004 I started a company with Joost Langeveld, doing a lot of commercial-based music production and audio post. In the last couple of years, in addition to running the music and post-production businesses we formed some record labels and a music publishing company so at times I have been right back into mixing and producing new artists.”

Over his time in the music industry van de Geer has racked up a raft of achievements: Stellar* had three top 10 albums and he has twice won the categories of best sound engineer at the NZ Music Awards (as well as best producer, as part of Stellar*). He also continues to play live in his new group, Delete Delete. Yet his memories of being in Second Child remain important to him. “In 2016, we put the album [Slinky] up digitally and I listened to it again. It’s aged really well, 18 years on. I’m still really proud of the album. I don’t know what lasting effect it had on anyone else, but for us it is a major part of our lives and created my bond with Damien. We’ll be friends forever and it’s all cemented from our time together in Second Child.”