Upstart music channel Max TV was an influential aspect of Auckland’s cultural landscape during the mid-1990s. It survived on chaos for over four years, before heavy-handed scheming on behalf of TVNZ nailed the coffin shut. “...and it’s more than what it might be...” As Chris Knox’s ‘Not Given Lightly’ diminished, Max TV’s transmission faded to black at midnight on December 3, 1997.

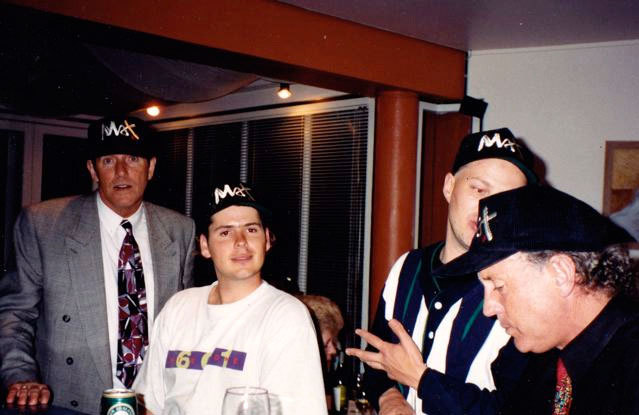

Max TV launch party: Kevin Black, Daniel Wrightson, unknown and Dale Wrightson - Photo courtesy of John McCready

The sad, bitter demise of Auckland’s independent music channel left an enthusiastic staff and large audience bereft. But for over four years Max TV echoed Knox’s sentiment and amounted to more than the sum of its parts, its vibrancy helping to galvanise Auckland’s music-obsessed communities.

Deregulation of the New Zealand television market under the Fourth Labour Government opened the door for independent operators such as Max TV. The new Broadcasting Act, introduced in 1989, smashed the state-owned Television New Zealand’s monopoly, as coveted UHF television frequencies were offered up to private enterprise.

The first incarnation of Max TV broadcast out of the offices of production company Vidcom.

A group of New Zealand FM radio pioneers, including renowned radio DJ Kevin Black and Stereo FM managing director Allan Rutledge, successfully tendered for a UHF frequency.

However their intention to launch a music television station, Much Music, stalled in 1991, and the frequency was sold off by the receiver. Auckland businessman Geoff Thorpe snapped it up at a bargain price, in cahoots with Kevin Black.

The first incarnation of Max TV broadcast out of the offices of production company Vidcom, near Auckland Grammar School. Thorpe was in partnership with Kevin Black, Vidcom owners Reston Griffiths and Andy Arcus (formerly of CBS Records) and music TV makers Dale and Daniel Wrightson.

“We went to air October 28, 1993 at 4pm with Hans Hoeflich as the first host,” Daniel Wrightson told AudioCulture in 2014. “We would have started work on it about March. At that stage it was called Bob TV as we didn’t want anybody to know what the name was, right up to the day we launched. Dale and I drew the Max logo. If the M looks familiar, if you look at Interview magazine and turn it upside down, their W was the inspiration.”

Francesca Rudkin interviewing Zane Lowe - Photo by Murray Cammick

Daniel Wrightson was the programmer and found the on-air talent for Max TV and Dale Wrightson did advertising and marketing assisted by Nikki Tysall. With the assistance of the TVNZ subsidiary Broadcast Communications Ltd, they used a microwave link first to the TVNZ studios on Victoria St, and then to the Waiatarua transmission mast in the Waitakere Ranges.

Although this transmitter reaches most of Auckland, few homes at the time had UHF aerials, except subscribers to the relatively new Sky service. The enterprising Max TV start-up actively promoted UHF aerials within their Auckland catchment.

95bFM's Wendy Adams at the Max TV closing party - Photo by Murray Cammick

It was difficult going for the fledgling station, as advertising agencies were reluctant to come on board due to the dearth of hard numbers around audience measurement. The only competition Max TV had were the meagre portions of time TVNZ and recent arrival TV3 saw fit to dedicate to music programming.

This combination of factors meant that TVNZ didn’t view the new music channel as real competition. “They saw us as amateur and they didn’t like the format,” Thorpe says. “And the major agencies told them we were not a threat. So we had a relationship with them that was essentially them humouring us.”

Nathan Rarere, host of Box Dog, Universal Records' Nicky Jarvis and Grant "Sample Gee" Kearney, host of Pulse - Photo by Murray Cammick

Despite being run on a shoestring, Max TV quickly gained an audience amongst the music hungry youth of Auckland after its launch in October 1993. Thorpe and associates couldn’t have timed it much better to tap into the Zeitgeist. It was the summer of the first Big Day Out festival in Auckland, and there was a massive upsurge of interest in music that simply wasn’t being aired elsewhere. The inaugural festival, featuring Smashing Pumpkins, Soundgarden, and The Breeders, represented a gathering of the tribes, a confluence of fans of various music styles coming together. “The Big Day Out was where we really excelled,” says Thorpe. “It gave Max a big boost, and I think we gave it a big boost.”

Max TV happily catered for them all through both its specialist and general music shows, including Pulse, True School, The Tube, The Rock Show, Monitor, and Pixel, while also offering a good dose of anarchy with Chat Bungalow, Box Dog, Serious Fun, and others.

There was also a high proportion of New Zealand music shown at a time when music video broadcast opportunities were scarce.

There was also a high proportion of New Zealand music shown at a time when music video broadcast opportunities were scarce. “It really gave New Zealand bands a bit of a leg up,” Thorpe considers. “We’d have them in the studio for interviews and record them playing live.”

The station thrived on a roster of paid talent, both young and experienced. Amongst them were ex-Th’ Dudes vocalist Peter Urlich, New Zealand dance music pioneer Grant "Sample Gee" Kearney, hip-hop legend Sir-Vere, and fresh talent drawn from student radio including Hans Hoeflich, Aaron Carson, Zane Lowe, Francesca Rudkin, and Nick Dwyer.

Presenter Hans Hoeflich. ©️ Rob Read Photographer. Graphic Design by Marcus Ringrose. Published in Pavement magazine

Dwyer, who has pursued parallel careers in DJing and broadcasting since, began at Max TV as a 14-year-old, presenting both Power Play and The Nick and Steve Show. “Within our age group, if you were a fan of music, it had such a major impact,” Dwyer says. “Being that age and being out at gigs and everyone recognising your face is a weird thing to have all of a sudden. But we loved it and I have no problem saying we were completely precocious little shits.”

While it was fun, and interviewing heroes including Foo Fighters’ Dave Grohl and Sonic Youth’s Lee Ranaldo was a thrill, Dwyer remembers Max TV generally being a chaotic, low-budget affair.

Luke Nola, who hosted the crazed and often inspired non-music shows Chat Bungalow and Box Dog, says that the walls of the studio were so thin that they could gauge how successful a show was by the laughter emanating through them.

Max TV editor and cameraman Seth Wilson with Johnnie Leech - Photo by Murray Cammick

He and co-presenters including Peter Robinson welcomed a revolving cast of guests onto the show – piercers, tattooists, prostitutes, tow-truck drivers, a dominatrix – to keep the fun flowing.

“Basically we just went into Max TV on a Wednesday night, had a few beers, and did some crazy stuff,” Nola says. “I used to like cutting things out of cardboard, making finger puppets, making lots of mess and doing stupid things on TV with bits of old meat and shaving cream. It was kind of like a whole bunch of kids playing television, which is what the best kind of television is.”

From December 2, 1994, the Wrightsons were also producing the Juice TV overnight music channel for Sky TV’s Orange channel, in Max TV’s early morning down time.

“Max TV was all well and good for the first two years. It was my and Dale’s baby. We were doing $2 million in turnover. We thought, why don’t we make an offer to the other guys, as this is our passion and where we are going in life. We made an offer of $2,100,000 and they accepted it in a tacit way, on the Friday of Labour Weekend 1995 and on the Monday they reneged and said, ‘Actually we’re going to run it and we don’t need you anymore.’ ”

“It was acrimonious and nasty. We then had no voting rights and potentially, financial responsibilities, so Dale extricated and abdicated ourselves of having anything to do with it. The other two partners had only provided facilities and the licence and we’d provided all the advertising income to pay the presenters. I said to people like Zane Lowe, ‘you’ve got gigs here, don’t worry about us, get back in there and carry on with your work.’ The only money we got out of Max TV was a third of the value of the transmitter, about $15,000.”

Daniel’s assistant Eddie Hribar stayed on to programme Max TV and he was followed by Brigid Reilly. “Our ethos was always to make a commercial product with wide appeal,” reflected Daniel Wrightson, “but we brought in programmes like Box Dog and brought in people like Zane Lowe, Sample Gee and Toni Marsh. They were all people I picked and put in place. The people who followed had more of a bFM style, but just being live made Max TV edgy.”

In 1996, Reston Griffiths and his partners sold Vidcom to the nascent Aotearoa Television Network and further chaos was thrust upon Max TV. Thorpe and Black became the sole directors of the station. They were left in a difficult situation, needing to buy their own equipment, with little revenue coming in, and dealing with new landlords.

By then Max TV had moved to a cheaply refurbished studio above the Ponsonby Post Office, on Three Lamps corner.

“I’m not sure if (the Aotearoa Television Network) wanted us there or not,” Thorpe says. “They were of a different world really. In 1997 the Aotearoa Television Network would ignominiously collapse, with their over-spending exemplified by director (and NZ First MP) Tukoroirangi Morgan’s purchase of $89 underwear.

By then Max TV had moved to a cheaply refurbished studio above the Ponsonby Post Office, on Three Lamps corner. Here the station gained more of a foothold in Auckland, and Thorpe and Black investigated the possibility of bringing MTV to New Zealand. Black was friends with Brent Hansen, the expat-Kiwi then helming MTV Europe, who the Max TV directors were told to deal with over the MTV franchise licence.

“We saw Max as MTV, but with more of a New Zealand focus,” Thorpe says. “When MTV started looking at New Zealand we jumped on a plane and rushed over to the UK. We were negotiating with them in London, and TVNZ unbeknownst to us were talking with New York. We got the bum’s rush and got on a plane and came home. We got quite determined then, and thought we’d take the bastards down because we thought we had more pulling power than MTV.”

TVNZ launched MTV in New Zealand in May 1997, and then head of television the late Neil Roberts was cynical about Max TV’s chances of survival. “I don’t think they have a future,” he stated. But by now Max was fairly entrenched, and even the advertising agencies were bringing a small part of their spend to the channel.

“Before that we managed to get money from people who liked Max, who felt it was good for their product and that they were speaking to their demographic,” Thorpe reflects. “But we never really made any money, but I guess that’s because as we increased what we took in, we increased what we were doing.”

Although TVNZ had been forced to offer MTV free-to-air due to Max TV’s presence, the network had other ways of forcing their advantage. Their tactics included drawing Max TV’s advertisers away from the small station, by offering free advertising on MTV with paid slots on TV2.

Thorpe and Black had been considering selling Max TV for some time due to the constant financial struggle. They made it public knowledge that they were considering expanding the station to the other main centres, or perhaps selling it to Australia’s Channel Seven. TVNZ’s Neil Roberts was soon on the phone.

“We had quite a yak,” Thorpe says. “And he said, ‘what would it cost for you guys to move out of there?’ Within an hour we had done a deal and sold them the frequency and everything. If they were going to touch anything they wanted the lot.”

TVNZ company BCL paid somewhere between one and two million dollars for the channel, with Max TV’s directors knowing that the sale meant it would be shut down. On December 2 1997, TVNZ announced that Max TV would cease broadcasting at midnight the following day. Thorpe and Black were able to walk away from their four-year long foray into music television without losing money.

Many members of Max TV’s loyal audience congregated outside its studio on that Wednesday night, as its demise was bitterly lamented.

However, others involved with Max TV struggled with its closure. Many members of Max TV’s loyal audience congregated outside its studio on that Wednesday night, as its demise was bitterly lamented during the final broadcast.

Dwyer had already left the station, but was back in the studio that evening. “That final broadcast will go down in urban folklore,” he says. “A lot of presenters got very drunk and said a lot of things they shouldn’t have said live on air, and probably shot themselves in the foot for any potential media career - especially at TVNZ. I know Neil Roberts had many horrible things said about him that night.”

MTV DJ Mikey Havoc, a friend of many Max TV staff, added fuel to the fire, faxing an epistle suggesting the blame lay with the sellers, not the buyers. “You are championing the wizened husk of Max like children defending a runaway father (or fathers),” he concluded.

Journalist Russell Brown wrote about the circumstances surrounding the closure in his Hard News column. “The evening began pretty, but by the end there were some dumb things being said and done,” Brown noted. “Eventually, Chris Knox’s ‘Not Given Lightly’ trailed away into black and the video signal cut out, which was mildly shocking – like a respirator being unplugged or something.”

That last song was chosen by Max TV producer Leanda Borrett, "I had the last word before the station went off air....and I chose 'Not Given Lightly' as our last song." Borrett was the only person present that day who had worked with the station since its inception. She recalls, "I was one of those people in the background shoving tapes into a machine, and also spent some time being Zane's producer", before becoming the "music programmer and the dark overlord of the transmission controllers".

Half a year later, MTV, the channel Max TV had been terminated to make way for, also had its plug unceremoniously pulled by TVNZ. Undoubtedly Max TV had left its mark on the Auckland music community of the mid-1990s, and spawned a number of talented broadcasters, including Zane Lowe, who is now a renowned music broadcaster in the UK.