AudioCulture

The noisy library of New Zealand music

Te pātaka korihi o ngā puoro o Aotearoa

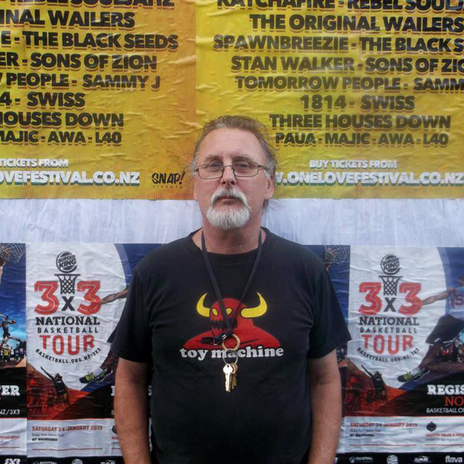

Brian Wafer

His record shop and label, Ima Hitt, has been responsible for numerous local releases. The gigs he has organised or assisted with are too many to be listed and the number of posters he has and continues to put up around the city, is a work that will probably remain in progress for the rest of his life.

Born and bred in New Plymouth, Brian’s introduction to live local music began somewhere in the mid-to-late 1970s. It was a scene you could have found duplicated in any number of places around New Zealand.

“Creativity was seen as playing other people’s songs really well,” he tells me. “Pink Floyd, Genesis, Steely Dan, Little Feat. It was good but I just got sick of it. There was no spark. Some of the people were OK, but there was nothing rock and roll that really inspired me, or made me think that I wanted to do something.”

“I had a job as a commercial cleaner. No idea what I really wanted to do. I knew you had to work to earn money, but I didn’t really like going to work. It was just what you had to do, so you did it. I was always going to garage sales and buying records. I bought as many as I could. I just thought I wanted to spend my whole life buying records, and hopefully, going to see some good shows.”

The arrival of punk rock, both internationally, and later locally, caused a life changing epiphany for Brian.

The arrival of punk rock, both internationally, and later locally, caused a life changing epiphany for Brian. “I think that might have been an angry time in my life. You know like domestic issues and all that, and noisy abrasion was perfect.”

The DIY aesthetic connected with punk also appealed to him. He decided from this point on, that he “wanted to work with the things I enjoy”. “Punk made me think that way, or helped me to think that way,” he says. Life had a new set of reference points, and Brian’s worldview was changed permanently.

He rented the upstairs floor of a building in Devon Street. He chose 50 records from his burgeoning collection that he didn’t really want, and with a $12 float to kick it off, Ima Hitt records was in business. The shop moved its location, “sometime around the end of 1980, or the start of 1981” to Brougham St. “Richard Clemance had a shop there called 48 Records. I took over from him.”

The hire purchase of a $600 duplicating cassette deck allowed Ima Hitt to issue music by local acts, and Brian’s shop, and his steadily building list of contacts, were able to help in getting the tapes out there.

At the same time he was doing poster runs around town for various venues. This had been prompted by meeting Chris Knox in 1979 at a sparsely attended Toy Love show, somewhere in New Plymouth. Brian asked Chris why there were no posters around town. Chris said that the band had sent 200 down, so Brian asked the barman where they were. “Over there on the floor,” came the reply. Clearly there was room for improvement, and as time went on Brian eventually gained some sort of remuneration for the work he was doing in this area. Peter Campbell (who went on to run The Powerstation in Auckland) “got me to do the postering for a band called Knightshade for their New Plymouth show. That was the first time anyone ever paid me.”

As the 80s progressed so did Ima Hitt, relocating back to Devon Street, this time on the ground floor, and building to a point where in 1987 ( with the help of Karl Iveson, who fronted the money) Brian was able to issue his first vinyl release. What Is This Place?, a compilation of local acts playing original songs, defines a time and attitude in New Plymouth’s musical culture more completely than any other work before or since. Brian had a list of acts that he asked for material, but no preconceived idea of what or who would eventually go on the album. He knew he “wasn’t going to be the judge and jury. If they think they’re ready, then let’s do it” is the way he explains it. He asked around 15 bands. “The ones who got their songs in first were the ones that got on the record,” he says.

By now a typical day went something like this: “I’d be getting up in the morning at 5.30 to go postering first, come home, have a shower, drop the kids at day-care, then go to the record store for the day, buying records, writing letters, sending stuff out. Order five of something, getting the band to play New Plymouth when they were on tour.” Often people would come in with tapes of their songs, and Brian would “always listen to it”. When the record store shut for the day he’d “do whatever”, which meant live shows or home on the phone, attending or organising. Brian’s contacts overseas were now an ongoing part of the scheme of things, but different time zones could often lead to long nights.

As Ima Hitt continued to build its catalogue it was able to exchange stock with various labels outside of New Zealand.

As Ima Hitt continued to build its catalogue it was able to exchange stock with various labels outside of New Zealand. Brian was able to get albums like Bleach by Nirvana direct from Nils Bernstein at Sub Pop. “I got 100 copies. I asked a few of the other shops around the country if they wanted to stock it, but they weren’t interested. Then when Nevermind came out they rang me to see if I had any copies left.” Of course all the copies of the earlier album had already sold, but as Brian is quick to point out, it was a learning curve for everyone involved.

At other times a certain amount of inspiration or improvisation would be required to get the job done. By now Brian was working with International acts when they toured New Zealand. When German Band Pungent Stench played here, there was no photograph to accompany a newspaper article planned for them. Brian substituted a photo of a band from Masterton called Carnage instead. “They were both trios with long hair.” Nobody knew the difference. “We did 27 internationals,” he adds.

To get Sticky Filth, who had somewhat of a “bad reputation” at the time, booked into the White Hart, Brian advertised them as the Shady Front Blues Band. He told them to “start the first couple of songs with a bit of 12 bar blues.” Things were bound to work out. And they did. By the time the owner figured it out his bar was full and doing great business. “He was pissed off, but happy with the big crowd,” Brian recalls. It certainly wouldn’t be the last time Sticky Filth played the White Hart, but next time they wouldn’t have to change their name to get a booking. Moments like these changed the landscape in New Plymouth’s nightlife. Sticky Filth’s various appearances at the White Hart over the years have become a memory shared by many, to the point where this band and this venue have become the image most associated with New Plymouth music.

Brian’s budget was usually very limited for many of the endeavours he undertook, and he often took the brunt or shared the load of expenses if things didn’t work out, especially at local shows. The cost of the PA would often be in his name, and it wasn’t always easy when it came to the end of the night.

“No one teaches you this stuff. You have to learn how to handle negotiations. You have to learn how to say, ‘OK, say with Sneaky Feelings, you’ve travelled this far, and there’s 20 people in the room. The PA is $400. Maybe you should’ve known that before you travelled this far, but [laughs] you know, you wanted a show and we’ve set it up for you, and this is what it’s cost to set up.’ ”

In situations like this Brian would do his best to make sure that “everyone at least had enough to keep going,” which meant he was often left to cover any shortfall. “At the end of the month I’d receive a monthly account and I’d pay the PA bills out of the shop.”

This financial interweaving of live gigs and the record shop operations became increasingly necessary as Brian’s activities continued to expand and develop during the 1990s. “Roll it over. Like when we’d go away on tour. Some were great, they worked well. Others didn’t. You’d just come home and start a series of auto-payments. Like pulling rabbits out of a hat really, just to carry on.”

Until it didn’t. The IRD’s heavy-handed, perhaps even vindictive, handling of Brian Wafer, and the forced closure of Ima Hitt damaged New Plymouth music’s infrastructure in a way that made recovery difficult. Ima Hitt had released more than 20 records by local bands at this point, but now the shop was gone, and the shows were on the way out. “The day I stopped doing tours was after coming back from the Unsane tour. That did OK , but there was a hole where there should have been some money, and Mr. Whippy came up the street, and the kids wanted an ice-cream, and I didn’t have a dollar in my pocket. Not a cent. And I thought – ‘Right, I’m not doing this anymore, I’m just going to work for other people from now on.’ ”

And so he does. “We all change our pace and priorities,” he says.

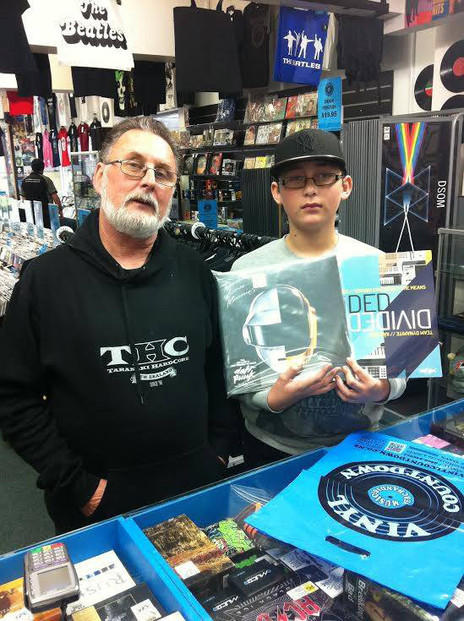

Brian Wafer’s still doing what he wants to do. He’s still doing poster campaigns. Still getting phone calls to help with shows. It’s just that he no longer has to carry the amount of responsibility that he once did. He knows how to roll with it. He’s still involved, just in a different way. Brian mentions Sticky Filth’s first gig at the Ngamotu Tavern, the first show he did with Rival State, or the debut of Ecnalg, (pronounced Glance Backwards) as some of the highlights from the local scene.

The first time he saw The Gordons in New Plymouth remains a vivid memory. The gig at the Army Hall or the various Mushroom Balls he describes as “brilliant”. He name-checks Slot Car as his current favourite New Plymouth band, talks about driving around Auckland with Jello Biafra and Simon Kay, and tells me he’s “been inflicted on Taranaki for a long time”. He’s a bit like Roy Colbert in Dunedin, I say. “Roy Colbert. Interesting guy. Every town needs a Roy Colbert,” he tells me.

New Plymouth scene 1987-2007 - thirsty work

Ima Hitt

Visit our sister site

NZ On ScreenMade with funding from

NZ On Air