AudioCulture

The noisy library of New Zealand music

Te pātaka korihi o ngā puoro o Aotearoa

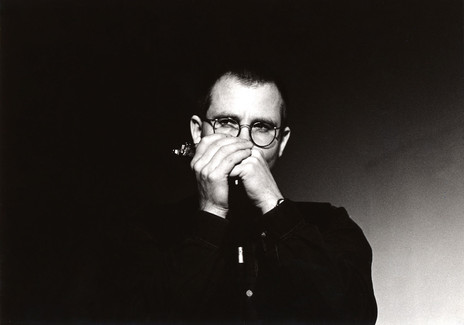

Brendan Power

It was the first step on a fascinating musical journey that has seen Power score international acclaim, not just for his playing but for his creative innovations on the instrument itself.

In an interview with AudioCulture conducted while he was on a December 2015 tour of Austria, Power recalled that pivotal concert. “Hearing Sonny Terry’s harmonica just blew me away and the next day I felt compelled to go out and buy one. It was like ‘wow, that sound. How can I do that?’ That was definitely a very formative moment. Sonny should have got a commission from all the harmonicas he sold at the back of his concerts. I certainly heard of other people who went to their concerts and then bought harmonicas.”

Born in Kenya in 1956, Power moved to New Zealand with his family at age nine. He spent his youth in Nelson, and, as he explains on his website, music was not a big part of his formative years. “I never played any musical instrument. My parents had some classical and Irish folk records that I enjoyed as a kid, but I was more into tramping and canoeing in Nelson's back country mountains and lakes.

“My musical understanding was zilch and I only owned one pop record: The Beatles’ Abbey Road. Hearing raw authentic blues for the first time, and particularly the blues harp, was a total revelation! I decided instinctively on the spot that I wanted to make sounds like those Sonny was coaxing from that little harmonica – an instrument you couldn’t even see behind his hands when he played … What a sound, what swing, what empathy. Sonny’s harp playing just took me by the throat and drew me in. It was raw and primitive, yet highly sophisticated at the same time, and it really moved me. I came out exhilarated.”

He recalls his first harmonica as “a new Hohner Marine Band, the 10 hole single reed diatonic harmonica that’s inextricably entwined with the history of the blues. Luckily the shop assistant was roughly familiar with the type I needed, and I didn’t get given a tremolo or chromatic."

Power says teaching himself to play rudimentary harmonica at the age of 20 was a real challenge. “I had no real clue about music at all then. I was musically illiterate, so just working out what a note, scale, and chord was proved difficult,” he told AudioCulture.

“In New Zealand at that point it was really hard to get information about what to do and how to play the thing! I played totally wrong for about the first year until it dawned on me to try something else with my lips to bend the notes. The self-taught approach can be slow as you make mistakes or do technically awkward things, but it does have benefits.

“I have often thought about this. You get schools of musicians, especially classical, who are schooled in a certain way. They can be technically brilliant but are extremely limited in other ways. It’s as if they can’t play a note unless they have a music sheet in front of them. Being self-taught, you have a more organic connection with the instrument. As with learning to speak as a baby, you’ve grown up with it, whereas if you’re taught a certain and regimented way, you don’t really get access to the other ways. On the other hand I’d love to be able to read music. I’ve tried, but it is still all by ear for me.”

At that time of the revelatory Sonny Terry and Brownie McGhee concert, Power was two years into studying for an arts degree at Canterbury University. He continued with his studies, juggling them with time-consuming devotion to his new love, the harmonica. “I played probably six to eight hours a day, driving my flatmates demented in the process,” he recalls on his website. “Somehow I fitted in the study for a couple of university degrees, but interest in academia was losing out rapidly to the obsession with blues harmonica.”

After a couple of years of home schooling on the harp, Power plunged into live performance.

After a couple of years of home schooling on the harp, Power plunged into live performance. “Christchurch at that time had a healthy folk scene, and I met up with a theology student called Peter Charlton-Jones, who played a mean blues guitar. We got together, stole the name Howling Mudbelly & Blind Boy Grunt from somewhere, and did our first gig at the University Folk Club. Amazingly, people liked us, and we started to gig sporadically at other folk venues. The student dances were great: lots of beer, plenty of flirting, and everyone in an exuberant mood. I also got exposed to bush band music, a peculiarly antipodean hybrid of skiffle and Irish music which was very popular in Christchurch at that time.”

Power graduated from university with a Masters degree in religious studies at the end of 1979. He had yet to fully consider music as a career option, but that quickly changed. “From playing around the odd bluegrass venue, I got asked to record on the debut album of a country singer called Patsy Riggir. The session was in Wellington in 1980, and it was enough of a draw to make me move there. I dossed in an old flat with a few other poverty-stricken musicians and a far more well-off prostitute, and kept practising.

“Eventually the recording session happened. It was my first time in a studio and I was very green, but the style of music was familiar by now, and I put all my Charlie McCoy licks to good use. Everyone was happy, and I got paid! I walked out the door with a big smile on my face, feeling ten foot tall! That was it: I was going to be a professional musician, no matter what.”

Power met guitar ace Red McKelvie there, and he offered to recommend Power for session work in Auckland. That was enough to lure Power there in 1981. “I was dossing on friends’ sofas initially,” he recalls. “I started to get a bit of paid music work, from sessions and playing in country and blues bands. However, it was a hand-to-mouth existence much of the time, and stayed that way through most of the Eighties.”

So-called “King of the Jingles” Murray Grindlay suggested that Power learn the chromatic harmonica, and he took this advice to heart, broadening his repertoire and employment opportunities in the process.

The then-bustling live music scene in Auckland also offered opportunities for Power. “The acoustic scene was thriving in Auckland in the 1980s, with some brilliant songwriters taking their first steps: Kath Tait, Wayne Gillespie, Julian McKean, Phil Powers, Sieffe laTrobe,” he recalls. “I joined a new folk band called Acoustic Confusion, which proved quite influential. Under the direction of band founder Chris Priestley we recorded an album called Hazy Days in 1984.”

On his website, Power recalls that, “Along with the folk scene I was starting to play in Auckland blues and rock bands. I was honoured to be the harp player in the band of the legendary Māori blues singer-guitarist Sonny Day. Sonny was an incredibly charismatic person and performer; he had what the Māori call mana in spades, and I learned a lot about life and music being around him. I was also playing bluegrass and country-rock with two well-known Auckland bands in the 1980s, Gentle Annie and Hillman Hunter and the Roots Group, the latter fronted by Al Hunter, a wonderfully warm singer-songwriter and human being.”

Power recorded his first album Country Harmonica in 1984. He explains on his site that “Erroll and Ginny Peters asked me to do a harmonica instrumental album of country tunes. They’d been to Nashville and bought a whole swag of pre-recorded backing tracks intended for singers to record over. The idea was to substitute the harmonica for the lead vocal.”

One glitch was that pre-recorded backing harmonies couldn’t be removed. Power notes wryly, “They give the finished product an endearing kitsch quality all its own.” The album was released on cassette only, and in small numbers.

Power began composing his own material in the mid-1980s. “My first tune was a Celtic-inspired instrumental called ‘Jig Jazz’, which has stood the test of time: I still play it on most gigs today. Other original tunes followed, and in 1989 I felt experienced and confident enough to want to record my first solo album.

A finished tape caught the attention of James Moss, owner of the independent label Jayrem Records.

“I recruited the services of Steve Garden to record and co-produce. He was one of NZ's best rock drummers and a brilliant, innovative sound engineer. I like working with smart, passionate people like Steve: you can have great arguments! The material, mostly originals in a wide range of styles, came out sounding fantastic, and I think it still stands up today for the quality of overall musicianship and recording.”

A finished tape caught the attention of James Moss, owner of the independent label Jayrem Records. As Power says on his site, the result was an unorthodox recording arrangement.

“James thought my talents could be put to good use playing more mass-market MOR sounds, so he made me a deal: he would release my originals album if I would record an easy listening album for him afterwards. I agreed, and State Of The Harp came out in 1990. It received good reviews and set me on my solo career.”

Power stuck to the deal, recording and releasing Harmonica Nights in 1990. “Though the music wasn't my personal choice, James’ commercial instincts were spot on,” says Power. “The album was soon licensed to overseas labels and has easily outsold any other albums I've ever made!”

Another varied album of original material for Jayrem followed, but 1991’s Digging In was not a commercial success.

Power now looks back on those days in the Auckland music scene with real affection. “It was thriving there then, and I was there all through the Eighties.

I co-formed a band called Working Holiday with singer Penni Bousefield and guitarist Lynne Campbell, with Billy Kristian’s son Daryn Karaitiana on bass. The live scene was thriving and we played all of Auckland’s many venues, the favourite for us and most bands being the Gluepot in Ponsonby.” Of his peers, he singles out the likes of Al Hunter, Mike Farrell, The Ebeling Brothers, and Sonny Day for special praise.

Pro harmonica players were a pretty rare breed in NZ then, as Power acknowledges. “Midge Marsden was a big name then. I was more technically minded whereas Midge was the big blues guy.”

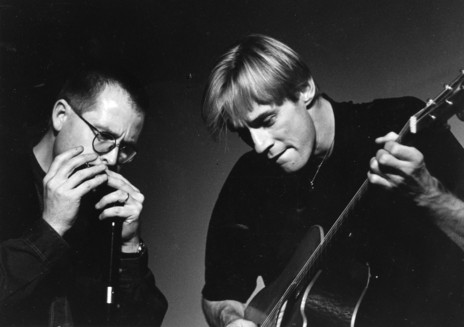

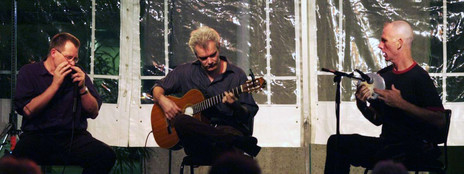

The greater musical opportunities offered in England (plus marriage to an Englishwoman!) led Power to pack his bags and harmonicas and move there in 1992. “Being big in New Zealand is not that big a deal outside the country, as we know,” he reflects with a chuckle. “I did make a name before I left, with the Jayrem albums and touring all over NZ a few times with my brilliant guitarist buddy Gary Verberne. Gary was already well known as an electric player in Dave Dobbyn’s band, but he welcomed the chance to strip it down to bare bones in a powerhouse acoustic duo. We played all kinds of venues from big rock pubs to little folk clubs, from Kaitaia to Invercargill, and recorded a couple of cassette albums to sell on tour (Live at Scoop de Loop and Licks and Spits). Great gigs, good times – and decent money too!”

A degree of antipodean success didn’t exactly mean a red carpet was awaiting Power’s arrival in London. “I sent out these various cassettes of my music when I got there,” he says, “and I heard nothing for six months.”

Opportunity then knocked in the seemingly unlikely form of British rock superstar Sting. “Out of the blue I got a call that Sting wants me to record with him,” says Power. “It was from nothing to ‘wow!’ He picked me up in his car and I recorded a couple of tracks on his album then he drove me down to his own studio. I think he was trying to suss me out – ‘who's this weird guy from the middle of nowhere?’ We played a bit of chess and did some other things together. He has a lovely house out by Salisbury, near Stonehenge. We did some recording for a video there and went over to Paris and did some stuff. For maybe a month I was around his entourage a lot, while the album was being promoted, then it was back to normality.”

Power’s playing can be heard on albums by Mary Black, Kate Bush, Sting, Van Morrison, James Galway, Paul Young, Shirley Bassey, John Williams, Mike Batt, and more.

Having that credit on his resume certainly helped his cause, and in the two decades since he has been involved in many other star-studded projects. Power’s playing can be heard on albums by Mary Black, Kate Bush, Sting, Van Morrison, James Galway, Paul Young, Shirley Bassey, John Williams, Mike Batt, and more.

“In many cases I never met the artists at all,” acknowledges Power. “You just work with the engineers and the producer of the album. I do enjoy session work. It is quite a challenge as essentially you are just a tool in their toolbox. They have the idea of what they want and they use you in a certain way. You have to put aside your own view and you focus on what they want. They may say ‘do your own thing’ but that’s within a certain parameter. That is the craft side of music, using your skill to add to what they're trying to create. My preference is to do my own thing, but that [the session work] certainly pays a lot better!”

Another big career break for Power in the UK came via his 1994 album New Irish Harmonica. On his website, he explains: “This album started out intended as an instructional cassette on how to play Irish tunes on the harmonica. Dave Mallinson (well known in the English folk scene for his successful range of tutor books and tapes for Celtic musical instruments) heard me playing a few Irish tunes in solo shows, and suggested a collaboration with guitarist-producer Chris Newman to make an instructional tape. A couple of months later Chris and I got started. After the first day, we were having too much fun to stop at an instructional cassette, so we persuaded Dave to invest a bit more and put the project out as a CD on his new label, Punch Records.

“Though it got very little promotion, the album somehow made its way into the hands of Radio Galway, on the west coast of Ireland, who gave it quite a bit of airplay. As a result, Irish musicians heard the music and, out of the blue, I started getting calls to come over to Ireland and guest on other peoples’ albums, play on film soundtracks etc – a process that eventually led to a gig in the Riverdance show.”

In his AudioCulture interview, Power recalls that “when I came over to Britain, I was still playing a big range of stuff, but it was the Irish thing that got the gigs. After New Irish Harmonica ended up being played in Ireland a lot, I got all these calls to come over and play and record there on albums by legendary Irish trad musicians like Ringo McDonagh and Arty McGlynn. As a Kiwi (albeit with an Irish name!) I felt really honoured to be invited into that elite Irish traditional music circle.

“It was an accident in some ways. It could have been the blues or jazz side but I do have an enduring love for Irish music. In some ways I don’t like to be too identified with being an Irish musician but I have rather become that way. I do love playing it but I love playing plenty of other things as well.”

Power’s sudden popularity in Ireland led to a commission in early 1995 to compose the soundtrack for the Irish feature film Guiltrip, one he terms “a disturbing movie about love, deceit and murder in a small Irish town.” On his website, Power explains that “Hummingbird Records suggested making an album to coincide with the film’s release later that year, so I did some extra recording in Dublin and added a couple of tracks from New Zealand sessions that had never been commercially released. These were added to selected tunes from the film soundtrack.”

The resulting album was entitled Blow In, with Power noting that “Blow in is a term the Irish have for an outsider who visits and then sticks around, and in a musical sense that's what I’d become, as most of my work was coming from Irish sources by that time as a result of people hearing New Irish Harmonica. It fitted well with the double meaning of blowin’ the harp.”

He has not composed for other films, but Power’s skill as a harmonica player has been featured on at least seven feature films, including the high-profile Atonement (the soundtrack won an Academy Award in 2008), Pushing Tin (1999), Shanghai Noon, and The Next Big Thing (2000). Well-known British TV series featuring his playing include Billy Connolly in Canada, Auf Wiedersehen Pet, and Bruce Parry’s Arctic Series.

Two new Power albums were released in 1996. Dawn to Dusk is a compilation of material selected from five earlier albums. “They were selected by James Moss of Jayrem Records for relaxed listening. They are all ballad tempo tunes in a smooth jazz or celtic style,” says Power.

A more adventurous effort was Jig Jazz, a joint recording with Irish jazz guitarist Frank Kilkelly. “That was a self-financed album, recorded live to DAT master in 1996 to sell at our live shows,” says Power. “We toured quite a bit together before I got committed to the Riverdance show. Jig Jazz has quite a range of material, reflecting our live show.”

By 1996, Power’s career became closely intertwined with the Riverdance phenomenon.

Launched in 1995, this show celebrating Irish dance and music broke all records at the Point Theatre in Dublin and made a star of Irish-American dancer/choreographer Michael Flatley. It would go on to become an international sensation, visiting over 450 venues worldwide and being seen by over 25 million people. The music of composer Bill Whelan found Grammy-winning success, and a Riverdance DVD and album also topped charts.

Power attributes his participation in the show to the button accordion player in the original show, Mairtín O’Connor. “He was very interested in the affinity between the small Irish button box and the harmonica, and we always swapped a few licks whenever our paths crossed at gigs etc. However, it still came as a big surprise when he asked me to do the first London run as his stand-in.

“Eventually, when Mairtín left the show for good, I got offered his seat. I toured with the show for three more years, for the last two doing a solo spot on stage as well as the orchestra seat. It seemed to me early on that there was scope to do a stripped down recording of the music, more in a traditional Irish style, without the big keyboards, strings and percussion sound of the official album – and featuring the harmonica as the lead voice.

“Bill Whelan gave his permission, and this album was recorded in late 1996 in London. It is licensed to the Scottish label Greentrax, as well as JVC in Japan and Jayrem in New Zealand.”

Power terms the Riverdance music, “a real tough challenge to play on harmonica, and I found the only way to do it in a convincing and flowing way was to come up with some quite bizarre tunings, often specific to just a single tune. I’d never use them in any other context, but they did the job on the gig.”

His commitment to that show kept Power from recording his own material for a couple of years. In 2000, he returned to his blues roots with Two Trains Running, a joint album with British blues singer-guitarist Dave Peabody. “It was recorded live to DAT by Dave and myself in a couple of evening sessions, and released by Indigo Records in May 2000.”

Next up in the Power discography is Triple Harp Bypass, a groan-inducingly entitled album credited to the group Iron Lung. This comprised three harmonica players, Rick Epping, Mick Kinsella, and Power, backed by guitarist Martin Dunlea, and the trio occasionally gigged together.

A prolific recording artist, Power continued to release albums regularly. From 2000 to 2015, he has put out 11 albums (often in collaboration with other instrumentalists), covering wide stylistic terrain. 2011’s The Bulgarian Project and 2012’s New Chinese Harmonica reflect his interest in world music, while other albums mined more conventional roots music styles. The albums Lament For The 21st Century (2008) and Power & White (2009, with guitarist Andrew White, at one-time a New Zealand resident) appeared on noted US acoustic label Candyrat Records, with many tracks notching high YouTube video views (in the 100,000 to 250,000 range). Power was the first harmonica player signed to Candyrat.

His 2008 album Back To Back drew kudos from blues harmonica great Charlie Musselwhite.

His 2008 album Back To Back drew kudos from blues harmonica great Charlie Musselwhite, who wrote to Power to say, “I love your Back To Back CD … Man it really wails. Great choice of tunes all played superbly.”

Power has always been naturally eclectic in his musical preferences and choices, something that has not always worked to his advantage. “It is not easy being eclectic in the British Isles scene. People do want to put you in a pigeonhole and there are these different festival scenes here. It’s like in the old record shops where you have different racks for different styles. If you cross over between them they don't know where to put you.”

He notes that, “There is definitely a New Zealand element in what I do, with the mixing and matching and pulling together of styles. In New Zealand, we don’t really have a musical folk tradition of our own. You could argue that Māori music was there though of course that had largely been obliterated by the Brits by the time I was born.

“Essentially we are picking and choosing from a wide array of world music, from mainstream pop music to ethnic folk music. I sense that Kiwis are more open-minded in experimenting than if you grew up with a strong ethnic style, like the Irish, Scots, or Bulgarians, for instance. Their history of music is in many ways set. Fooling around with it is perhaps frowned upon or the musos themselves would think it is wrong to do it, whereas for someone like me I don’t know what’s right or wrong. In some ways I think that’s an advantage. I see it as a bit like Pacific cuisine, which mixes and blends things willy-nilly, but often that can work in surprising and good ways.”

Power is something of a restless musical explorer, seeking out new musical cultures he can immerse himself in. “From time to time you get a buzz for a certain kind of music,” he says. “It might be gypsy jazz, Bulgarian or Chinese. I will explore that deeply then when I get the feeling I have a handle on it to some extent I record an album in that style, working together with some people I like in that scene. I have taught myself to be a reasonably good sound engineer and I have a little studio setup, so I can choose how we do it together. That's a periodic phase that comes and goes. It was Chinese on the last one.”

One relatively regular collaborator over the past decade has been Celtic musician Tim Edey, a highly-regarded guitarist, button accordionist and singer who has also worked with The Chieftains, Christy Moore, Mary Black and Natalie MacMaster. Power terms Edey “incredibly gifted.”

In 2011, Brendan Power and Tim Edey recorded a stylistically eclectic duo album, Wriggle And Writhe, one that led them to being named Best Duo of the Year at the prestigious BBC R2 Folk Awards in 2012. In a review on the BBC Music website, noted roots music scribe Colin Irwin wrote that the pair “blaze into the spotlight as a duo notable not only for virtuoso playing, but an incorrigible sense of fun and mischief not necessarily apparent in their other incarnations ...”

The pair have frequently toured together in the UK, Europe and North America, and have hopes of performing together in NZ for the first time, possibly in 2017. Power also guested on Edey’s 2010 album The Collective.

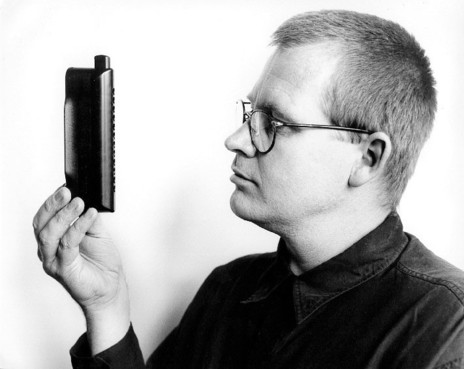

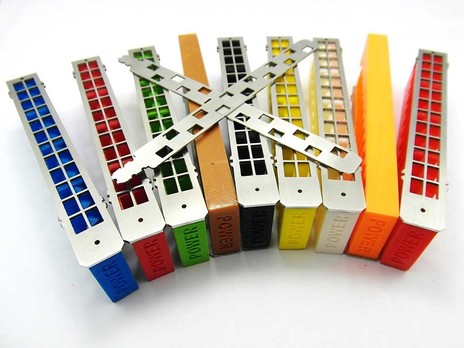

Running parallel with his busy career as a recording and performing artist, Brendan Power has travelled a fascinating path as a technical innovator with the harmonica. He has come up with original tunings that have found international favour with his harpist peers, and he has also made original and significant modifications to the actual instrument.

This urge to improve upon the conventional commercially available harmonicas started early, and Power attributes this to the DIY ethos of New Zealand culture. “In my experience the only way to get an authentic sound in a certain style of music I’m interested in is to actually modify the harmonica physically. I started doing that from an early stage. Maybe I got that from my dad, who had a great workshop at the back of the house and was always making things. I guess that is in my genes. Back in 1978, without realising it, I had invented a new kind of harmonica: the half-valved diatonic. From then to now, I’ve still played half-valved harps pretty much exclusively.”

Power explains that a half-valved harmonica is “a blues harp where there are windsaver valves affecting the lower-pitched notes in each hole. In addition to the normal bends, the valves allow you to bend those other notes too, which is not possible on a normal harmonica.”

He came up with these modifications for both diatonic and chromatic harmonicas, and they found industry favour. “Through instrument importer Riki McDonnell it came to the attention of Suzuki. They liked it, incorporated the idea into a new Suzuki harp, and they paid me a royalty for about five years. That harmonica, the MR-350 Promaster is still being made, and half-valving is a popular choice for quite a few players these days.” Impressed by Power’s expertise, Suzuki employed him as a consultant and promoter of their instruments from 2006 to 2012.

“I’ve loved mixing the two [the playing and modifying] and as a result I have all kinds of crazy tunings, some of which have become quite popular amongst other people. I’ve come up with some bizarre hybrid harmonicas too. I love that side of it as much as the playing to be honest.”

“I left Suzuki because I prefer the freelance approach, and I’m enjoying creating my own high-tech stuff now,” he explains. “I taught myself CAD design and got totally absorbed it, plus learned how to use the amazing new maker-machines available now. I currently have two 3D printers, a CNC milling machine and a laser cutter in my workshop, and just love the power they give me to create very complicated shapes and parts to realise my ideas. They make a good living for me too, as the parts I create (like my 3D printed PowerCombs) have become popular with players wanting to swap them into their own harmonica to make them play better.”

Power has patents pending on many of his designs.

“I have got to know some of the emerging Chinese manufacturing companies and already get several own-brand models made by them, in my own tunings. I have a Chinese business partner who ships them out around the world as orders come in.”

“I guess I'm lucky that the making and design of the instrument gives me more income than the playing and recording side. I imagine I'm in a better position than a lot of other musicians who rely solely on recording and performing. I do love it as well.”

Power has certainly earned the respect of his musical peers over the years. Toronto-based Carlos del Junco is recognized as a virtuoso harmonica player, and he tells AudioCulture, “Brendan is certainly a well respected innovator within the harmonica community who is pushing the boundaries of what the instrument can do. I can certainly vouch for his tireless efforts to ‘improve’ the diatonic harmonica and his wonderful and unique playing style.”

Power still believes there’s plenty of potential for improving the harmonica. “That is what I’m trying to push along, getting greater functionality out of it. Trying to create harmonicas that are louder, take big octave jumps more easily, have more ornaments, for example. There are limitations with the current models but I think there are ways to overcome those with modern design and technology.

If there is a world in a grain of sand there is a universe inside a harmonica, once you start looking. I guess I'll be obsessed with that exploration until I die. I don't think I have much choice really!”

Visit our sister site

NZ On ScreenMade with funding from

NZ On Air