Born in London, Burgess immigrated as a boy to Christchurch in 1959, where his father had been offered a job. This may have denied him the chance to see the emergence of swinging London, but by the time he could attend nightclubs, Christchurch had developed its own reputation for live music, after the success of bands like Ray Columbus and The Invaders and Max Merritt and The Meteors.

“The Christchurch scene was incredibly active at that time with many clubs. My favourite was the more underground blues scene at the Stage Door where I eventually wound up playing”, Burgess told Trevor Reekie in a NZ Musician interview.

Burgess gained a reputation as a drummer, playing in two bands with his long-time friend Barry Saunders (later of The Warratahs), and briefly moving to Australia with The Fantasy (later The New Zealand Fantasy Band).

Burgess found enough work as a musician to lure him away from the training he began in avionics with National Airways Corporation (NAC), but he retained a fascination for electronics. “While I was at NAC I bought myself my first stereo quarter inch tape recorder from a Dutch engineer I worked with. That was my first foray into recording music,” said Burgess. In later years with the band Landscape, Burgess would make successful live records by parking a slightly more advanced tape recorder behind the drum stool on stage.

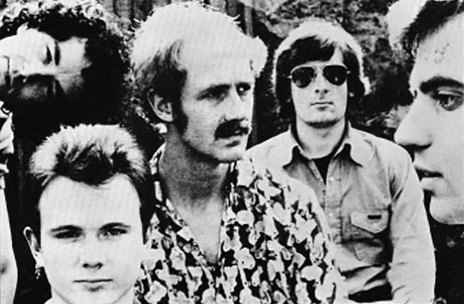

When the brilliant but unreliable drummer Bruno Lawrence was fired from The Quincy Conserve in 1970, Burgess received a call from producer Peter Dawkins to audition for the group, and after the audition, got the role on the spot. Burgess told Wallace Chapman, “I was incredibly punctual – sort of OCD. I put this in my books – sometimes you might not be as good as the best guy, but if you show up on time, you might get the gig … but the man was an incredible player, make no mistake, and frankly I was kind of awed to step into his shoes at such a young age.”

The Quincy Conserve gave him his first experience in the studio environment, recording the Epitaph album at HMV studios in Wellington.

The Quincy Conserve gave him his first experience in the studio environment, recording the Epitaph album at HMV studios in Wellington, where he stayed after hours, soaking in the experience of what he called “creativity, electronics and science and everything I’m interested in wrapped up in one ball.” Of Dawkins, who died in 2014, Burgess said “I was spoiled by how great the experience was. It was only later when I worked with lesser producers that I started to realise how great producers operate.”

Eager to develop his drumming further, Burgess successfully applied for a scholarship at Berklee College of Music in Boston to study under Alan Dawson, who had taught Tony Williams of the Miles Davis Quintet. He then returned to his birthplace, and helped by a recommendation from expat New Zealand singer Frankie Stevens, started getting session work in major London recording studios. Over the next few years in London he followed a “full boost at all frequencies philosophy”.

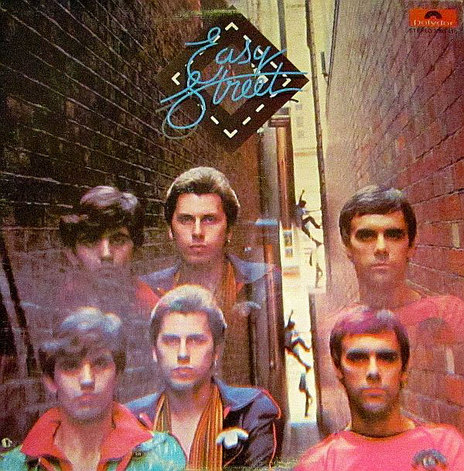

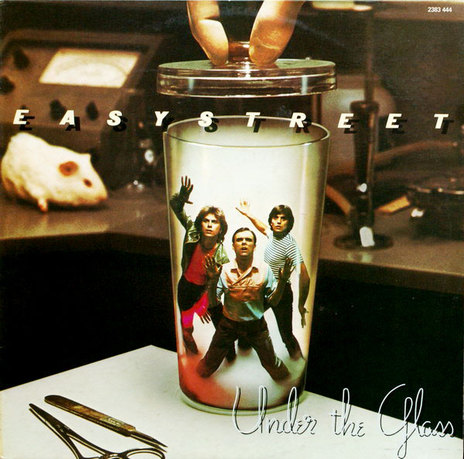

“I did everything I could – played sessions, joined as many bands as I could fit in and formed my own things as well ... I played straight ahead jazz, all kinds of fusion music, classical music and various types of rock, R&B, and funk.” His most successful acts became the soft rock band Easy Street, and Landscape, which was initially an instrumental jazz-funk band.

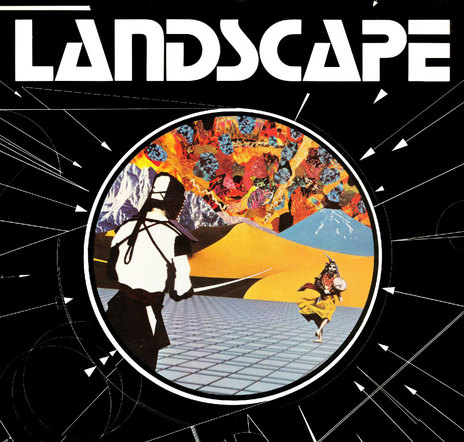

After a brush with success when Easy Street spent time signed to major labels, Landscape finally emerged as the more satisfying project for Burgess, and he eventually turned his full concentration to the act. Developing a crowd by playing close to 300 shows in a year, the band sold 25,000 copies of their self-recorded EPs, released on their own label Event Horizon Records.

By the end of the 1970s they could draw 3,000 people to a gig at The Music Machine in Camden, and labels started taking notice.

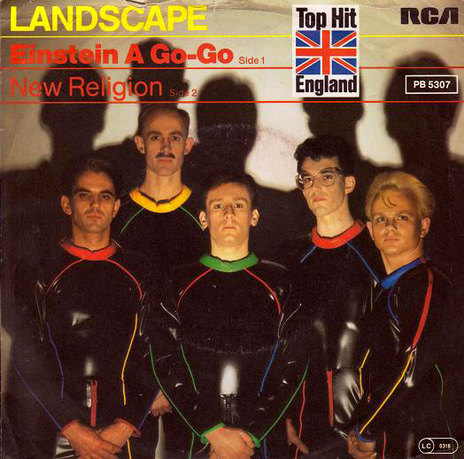

By the end of the 1970s they could draw 3,000 people to a gig at The Music Machine in Camden, and labels started taking notice. “At that point RCA offered us a deal. We took a vote, and with three for and two against, we took the deal. I was against signing and in favour of building up our own label. By this time I had been signed to three majors and I knew what was in store for us.”

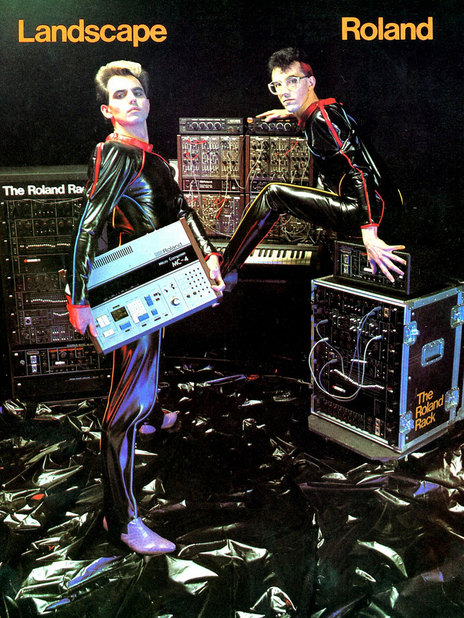

Burgess’ interest in electronics had been developing over this time. He played electronic percussion and synthesiser in avant garde electronic band Accord, who appeared on the BBC series Music In Our Time. He would become one of the first three people in the UK to own the breakthrough Australian sampling computer the Fairlight CMI (another was Peter Gabriel). To solve problems mic’ing drums on tour, he was developing ideas and prototypes for what would become the hugely popular Simmons SDSV – a fully electric drum kit that would dominate recordings in the 1980s. With its distinctive hexagonal drum pads, it become a recognisable prop in music videos and TV appearances.

“Everything was electronic in the band except the drums … the keyboard player, Chris Heaton, would play the drums for me while I set up the drum sounds, and I’d get everything set up and then I’d push the mics up for the drums and suddenly everything would degrade because all the instruments would bleed through them. So I thought, ‘this is bizarre – why are drums still in the Stone Age – basically skins stretched over logs?”

Because of his reputation as an electronic musician, Burgess was asked to produce the debut record of a band he’d seen at The Blitz, the London club night that became the epicentre of a new genre of music. The band was Spandau Ballet.

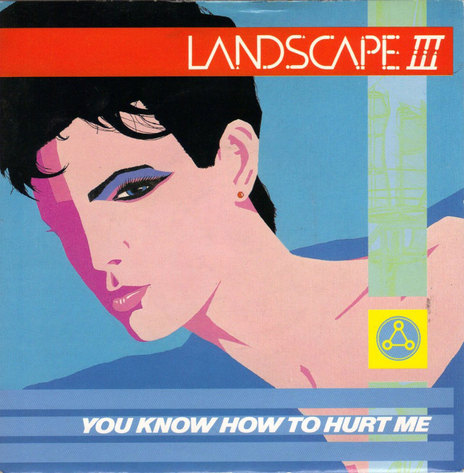

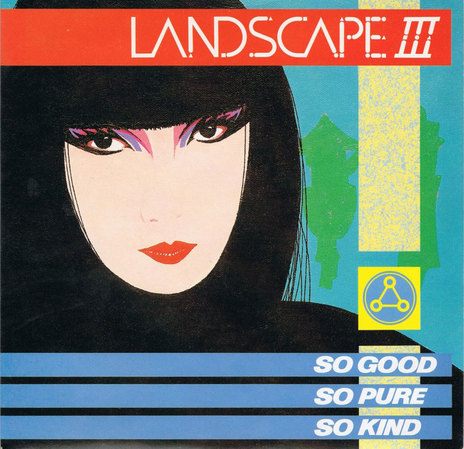

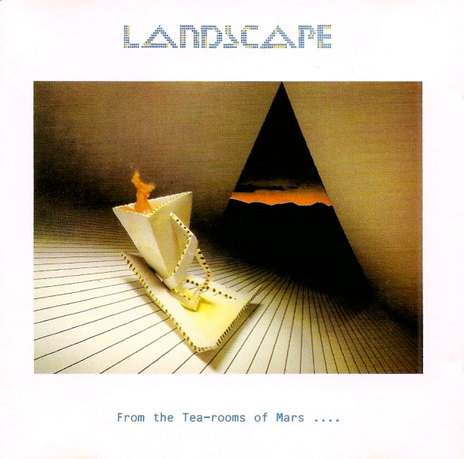

Landscape’s first album on RCA hadn’t done as well as the EPs they had released themselves, and the band decided they should bring their interest in digital music fully into the sound of their second album (Chris Heaton was also a member of Accord, and Landscape had already experimented with effects like digitally altered saxophone and Moog drum on their first RCA album). “I realised that we were going to get the same result as we did with the debut album if we put out another instrumental jazz-funk album through a major label.”

Burgess decided to let Spandau Ballet release the electronic album he produced with them first.

Burgess decided to let Spandau Ballet release the electronic album he produced with them first. “I knew that we could make a great album that would be a hit and that the Landscape album would be more likely to chart if I had a hit with Spandau Ballet first.”

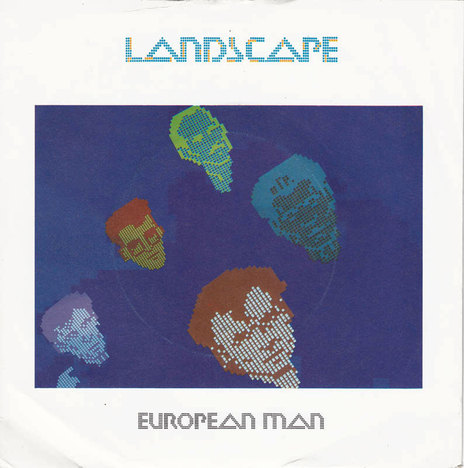

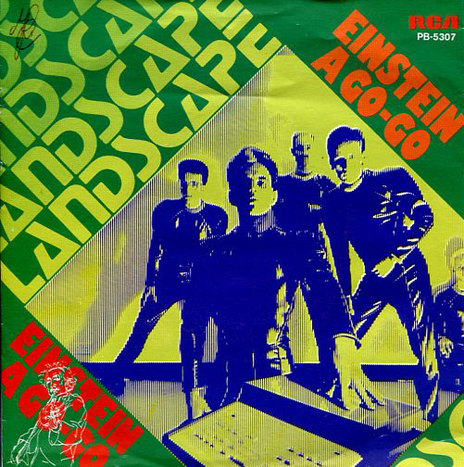

He was right. Not only did Spandau Ballet’s album Journeys To Glory take off, Landscape’s From The Tearooms of Mars To The Hellholes Of Uranus followed with a hit song, ‘Einstein A Go Go’, and the now futuristic looking band became stars. A new movement had been born and with an instinct for marketing, Burgess argued the movement needed a name.

He started using the term “New Romantic” (choosing it over other terms he had initially used, such as EDM for “Electronic Dance Music”, which would be recycled by a later movement). The name stemmed partly from the fashion sense of bands like Spandau Ballet and their fans who could be found at The Blitz, but the term would come to define the movement, even though some of Burgess collaborators disliked the term.

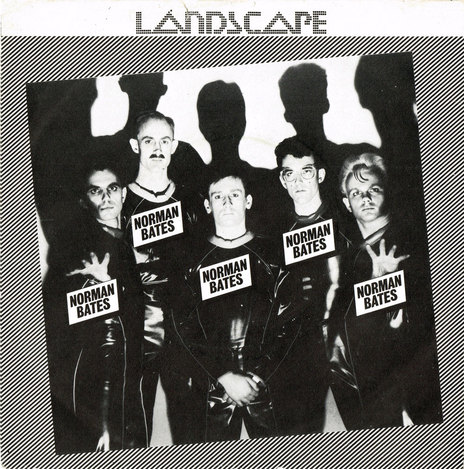

Burgess’ reservations about major labels proved well founded for Landscape. RCA got into a dispute with the (UK) Musicians’ Union, which meant the brilliant ‘Norman Bates’ music video couldn’t air the week the single came out. Burgess says the American branch of RCA seemed confused as to how to try to sell the band, even once MTV started in 1982 and ‘Norman Bates’ was being played regularly. “It is always frustrating to put as much effort as you have to into making an album and to then watch the label miss opportunity after opportunity. Along with the endless promotional touring these were the factors that drove me further toward producing.”

Burgess’ work with Spandau Ballet had put him in huge demand as a producer, and he now started to spend most of his time in the studio. “As a producer I could make many albums in a year whereas labels were tending towards one album cycle or less per year for individual artists.”

Kate Bush called him in to programme the Fairlight CMI on her Never For Ever album.

Kate Bush called him in to programme the Fairlight CMI on her Never For Ever album. He says of her, “That was a truly magical experience, I have to say. Kate is one of the most creative people I’ve ever had the honour to work with ... she really understood the Fairlight immediately.”

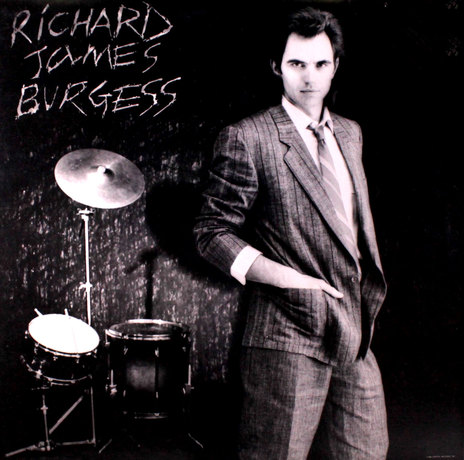

After Landscape folded in 1984, Burgess moved to New York, where he worked on Colonel Abrams’ debut album, including the proto-house hit, ‘Trapped’, using only a electronic few instruments he brought over from London. At the same time, he made a solo record for Capitol Records, distancing himself from the New Romantic sound, which he says was starting to repeat itself. Burgess also became a pioneer of 12-inch extended remixes, which allowed New Romantic bands and others to be played in dance nightclubs. In the mid 80s, he started using pseudonyms for these remixes and some producing jobs, so that his name wouldn’t associate the band with the electronic sound he was known for.

In 2001 Burgess brought his career full circle, accepting a position at Smithsonian Folkways Recordings.

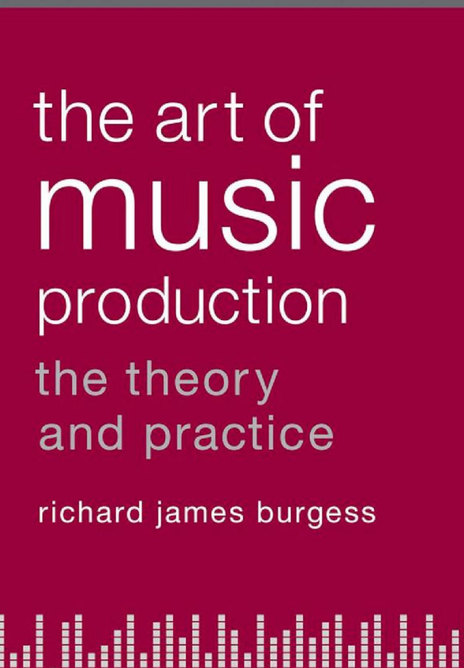

Burgess continued his education into the 1990s, eventually gaining his PhD and educating others: he produced the BBC radio series Let There Be Drums, and in 1997, published the best-selling book, The Art Of Record Production. A more holistic look at music production than Burgess could find in the more technically focused production manuals that came before it, the book is in its fourth edition (it was renamed The Art of Music Production: The Theory and Practice after the second edition). “Producing is a pretty catch-all term. It covers a lot of different aspects of what can happen in the studio, and I wanted to really document that so that it could be taught in schools, it could be understood,” he told Radio New Zealand in 2009.

In 2001 Burgess brought his career full circle, accepting a position at Smithsonian Folkways Recordings, the non-profit record label that has re-compiled and re-released some of the landmark recordings that first influenced Burgess. He was the Associate Director for Business Strategies at the organisation, of which role he said: “It is truly a full turn of the wheel … I remember standing in the World Record International (I think it was called) in Christchurch, at the age of about 15, holding a Lead Belly LP cover and listening to this incredible music on the headphones in the listening booth. We have that Lead Belly LP in our collection and we are just about to put out a new Lead Belly box set … it has been the perfect home for me for the past thirteen years.”

As of January 2016, Richard James Burgess is the CEO of A2IM (the American Association of Independent Music).

- Thanks to Trevor Reekie.