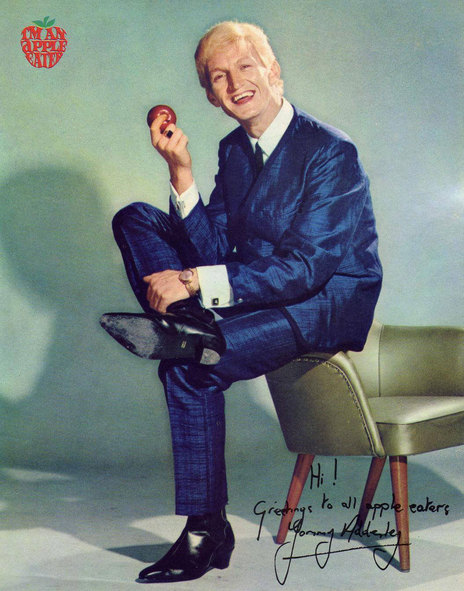

This is from a cassette recording of an interview with Tommy Adderley conducted by Roger Watkins in Auckland in 1992, a year before Tommy’s death:

“Once I was so hung out. I couldn’t get anyone in Auckland to give me a taste,” says Tommy. “I was sick, physically sick, really sick … I can remember ringing a guy in Hamilton and asking if he had any. ‘I can give you a taste, that’s all I can do.’ … I met this guy at the [Hamilton] Post Office … He gave me enough for a taste. We went to a field somewhere. We took our works with us, hit it up. By the time we got to Mercer on the way back I needed another one. The whole thing was a pointless exercise. By the time we got to Mercer I was thinking, where I was going to get the next one from?”

Merchant Marine

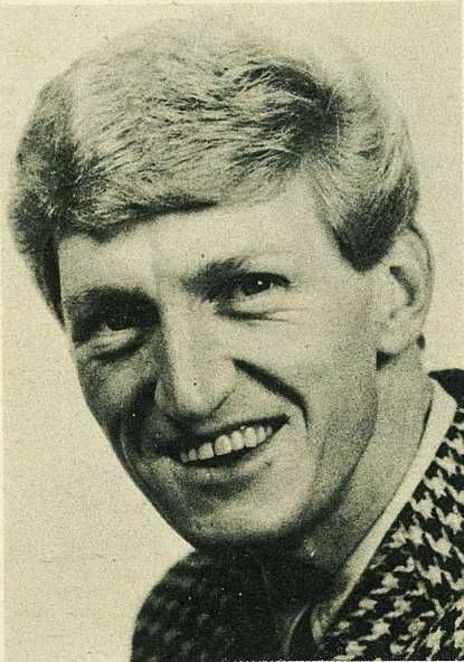

Tommy was Brit-born, Birmingham, April 7, 1940, a child of the Blitz. It was an age of music and bombs. His grandmother cleaned the Birmingham Hippodrome and Tommy watched the acts rehearse. People sung at home, in pubs, and family events. As a kid, he woke up singing. At three, he was demanding applause.

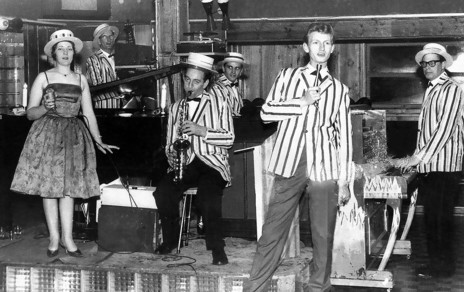

By his teens he was performing on the school-stage, winning music competitions, discovering a life-time love for cooking and dressing sharp. Then Tommy joined the British Merchant Navy, forming an on-board group, Tommy Adderley and the Hounddogs.

Long layovers in New Zealand gave him an intro to a new world, hungry for fresh sounds, wide-open for talent, and with women impressed by English style. Tommy liked colognes, clothes, and shined shoes. The Hounddogs gigged in all New Zealand’s main cities. He got a New Zealand girlfriend, jumped ship in Sydney so the arrest warrant would be in Australia, and was back in Wellington in a week.

On the road

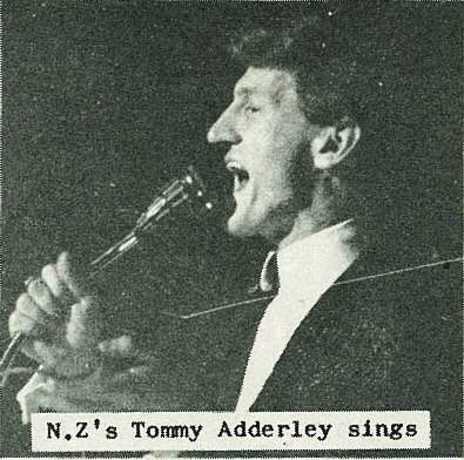

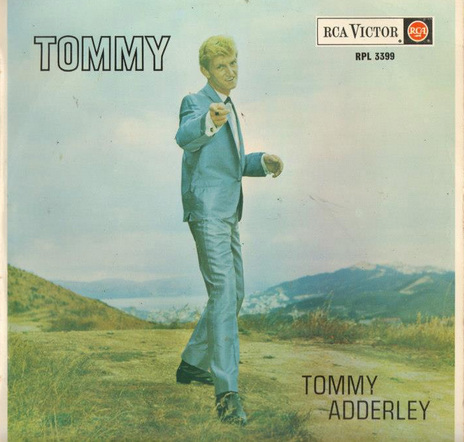

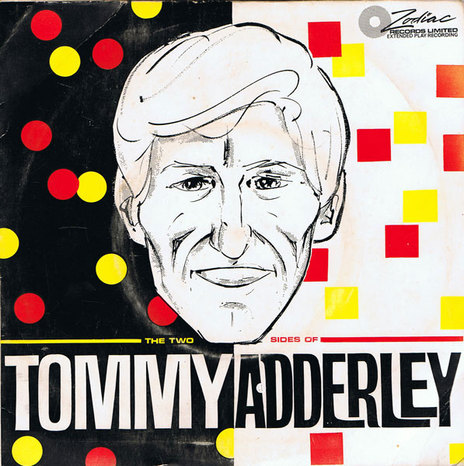

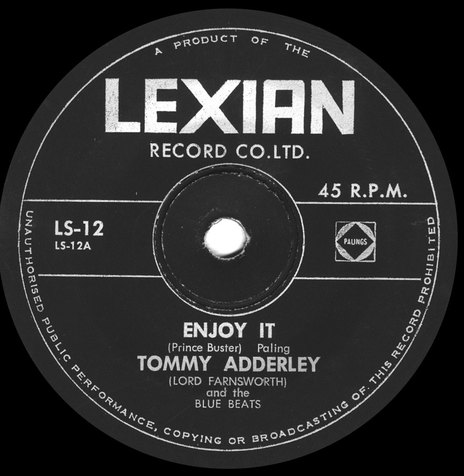

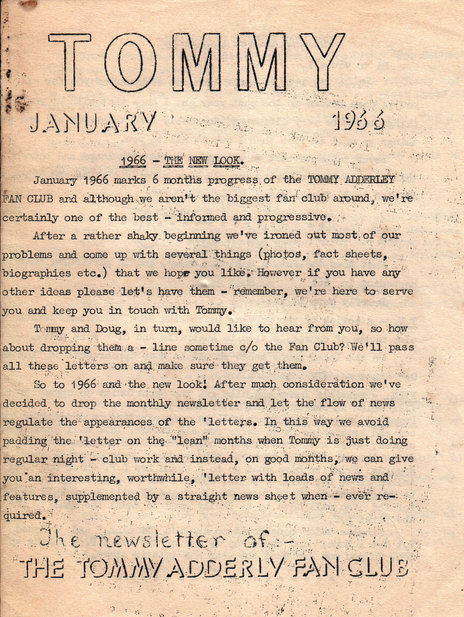

Tommy’s first album was vocals in front of imported backing-tracks. The lurid silver-mauve suit he wore on the cover was a shocker. He’d been working in Wellington, had a residency at The Pines in Houghton Bay. He’d learned the art of arrangement. He made recordings that were released on Lexian and RCA, but Auckland was bigger and so he made the upward move.

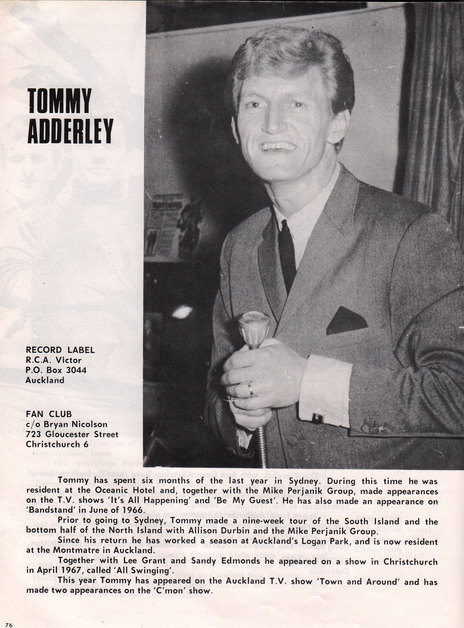

Tommy worked the Auckland clubs. It was an era of non-licensed venues. The Montmartre was home base, allowing him to return to jazz, but there was the Oriental Ballroom, the Crystal Palace, the Embers, and the Picasso. He was on TV now, In the Groove, Let’s Go, and Startime Spectacular. Programme producer Kevan Moore had tendencies to put Tommy in over-propped sets because Tommy’s looks weren’t televisual, but his singing won the fans.

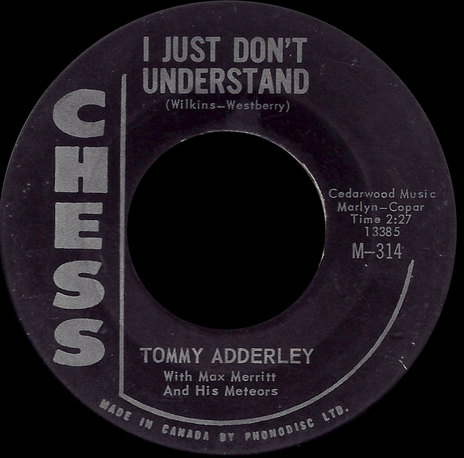

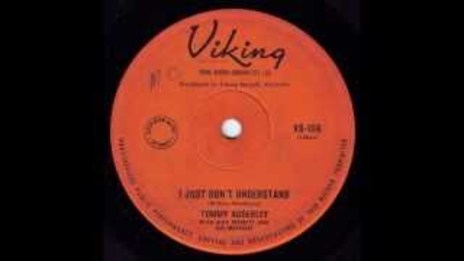

1964 gave Tommy ‘I Just Don’t Understand’ on Viking, a rearrangement of an Ann-Margret song, which would eventually chart in Australia, Canada and the USA. Its Merseyside sound and its international success reflected Tommy’s ability to tap into a zeitgeist with a nice bit of arranging and an assumed Liverpool accent.

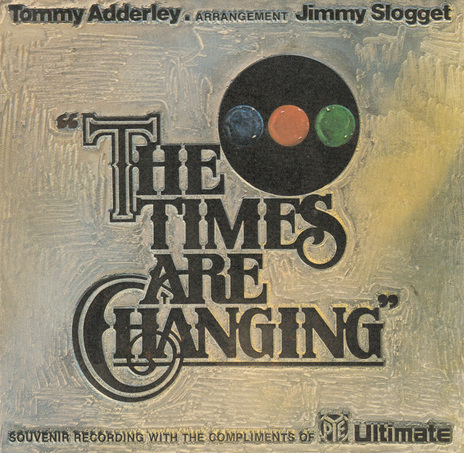

Life as a merchant seaman had prepared him for the road and Tommy toured. There were local whistle-stops, but there was also the packaged nationals. Let’s Go 65 had Tommy with Bill and Ben and the Jimmy Sloggett Showband. In Stars of 65 Tommy was placed with Peter Posa and the Doug Jerebine Showband. Swinging 65 featured Manfred Mann, The Kinks and Tommy. He toured with Sandie Shaw and the Pretty Things. There were months on the road in a bus. At home, Tommy’s wife received knickers in the mail, sent by motel and hotel staff returning ‘lost property’.

There was Australia and Sydney for two years. Tommy worked, gained a residency at the Oceanic in Coogee Beach, appeared on TV, but for him Australia was summed up by a sign he saw in Grace Brothers department store: ‘Three Santas. No waiting’.

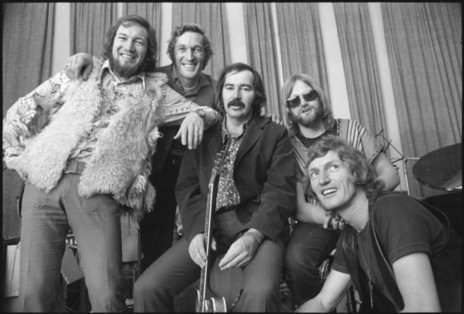

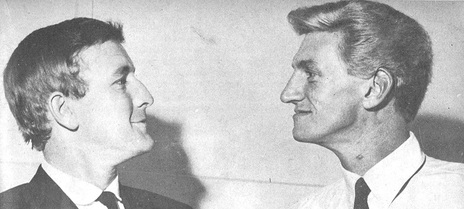

Back home, in early 1967, Tommy formed the Adderley-Walker Movement with Mike Walker. They worked the El Matador, easily Auckland’s most popular dine-and-dance, for 18 months, recorded the ‘Hooray for the Salvation Army Band’, before breaking up.

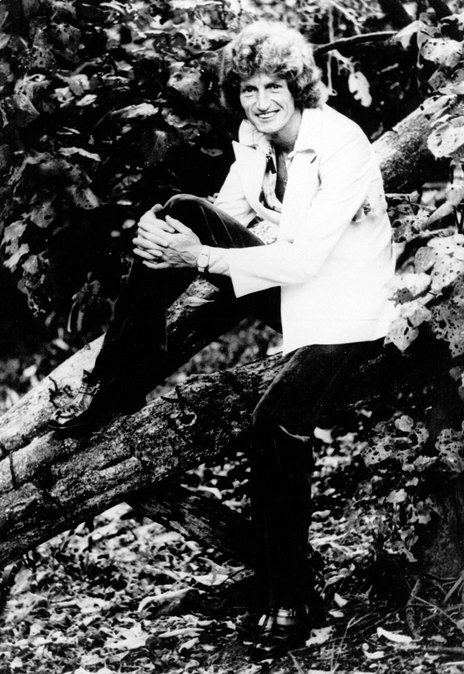

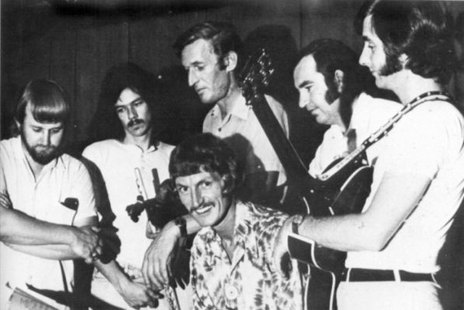

Then Tommy returned to his British roots with Headband, a John Mayall-influenced group. He originally planned to have no drummer but the idea was canned and Headband debuted at Molly Hatchett’s with Jimmy Hill as drummer, in February, 1971.

‘Good Morning Mr Rock ‘n’ Roll‘, which became the Headband’s most widely known song, getting to No.1 on the Radio Hauraki Hit List.

Headband’s album, Happen Out, came in 1972, with a large proportion of original material. The first single from the album, ‘The Ballad of Jacques Le Mere’ was followed by two others, the Adderley-written ‘Good Morning Mr Rock ‘n’ Roll‘, which became the Headband’s most widely known song, getting to No.1 on the Radio Hauraki Hit List, and ‘Love is Bigger Than The Whole Wide World’ which reached No.12 on the national Pop-o-Meter chart.

It also featured the longest track recorded in New Zealand to date, the 15 minute ‘The Laws Must Change’, about the marijuana prohibition. “Tight and gutsy,” the Auckland Star said.

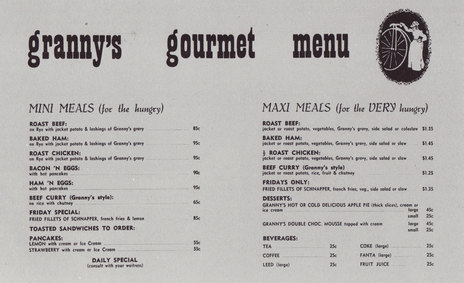

Granny’s and Grandpa’s

Tommy was bored with making no money as a gigging musician. He went into partnership with Dave Henderson, took on the old Bo Peep club in Durham Lane, refurbished it and opened it in 1971 as Granny’s. Headband became the resident band and featured alongside Dragon, Space Waltz, Rockinghorse, and Ragnarok in the new club space. It stayed open late in a country that had just got out of 6pm closing. It was unlicensed, but you could buy booze from a car boot out in Durham Lane. It provided Auckland with the best in alternative music.

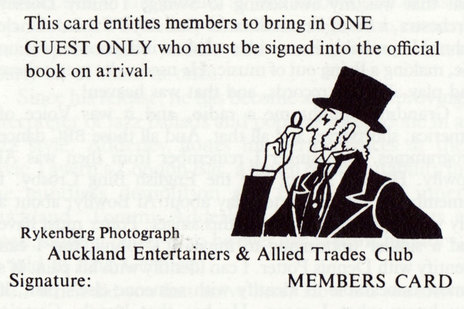

Tommy was on a roll and opened Grandpa’s in the space above Granny’s. It was a private club, members only, aimed at an older crowd and entertainment industry insiders. Tommy wanted it open late, until 5 or 6am, giving working musicians a place to wind down, the sort of place he’d want to spend time.

Grandpa’s was the Auckland club with everything for three years. It would attract a large number of visiting overseas musicians. Keith Richards played one night. There was the Joe Cocker Band, Led Zeppelin, Muddy Waters, ELO, The Temptations, Elton John, Leon Russell, Three Dog Night and more. Tommy hosted movie nights for members on Sunday, getting free prints from Columbia Warner vaults to screen at the club.

After more than $15,000 in fines, Tommy and Dave Henderson pulled the plug on one of New Zealand’s greatest clubs.

But Grandpa’s still didn’t qualify for a liquor licence. They tried ticketing and locker systems, but the law was a bitch. And the licensing raids rolled in regularly until after more than $15,000 in fines, Tommy and Dave Henderson pulled the plug on one of New Zealand’s greatest clubs. Tommy lost his house, his Daimler, the Monaro, and the land he owned on the Mahia Peninsula.

Sister Morphine

‘I Get High (On Music)’ was a track on the briefly reformed Headband’s 1975 album Rock Garden, but Tommy was getting high on a lot of other things too. It was the Mr Asia years and New Zealand was flooded with some of the most potent heroin in the Western world. Tommy preferred morphine for the tingle it gave his head, but it was a time of brown rocks and white powders that were sledgehammers for the synapses.

Tommy had smoked marijuana since 1959, but opiates were a different ball game. Danni Cohen offered him some pethidine, Tommy tried it. “It was like the sun coming out all over you,” he said. Then there was the habit, the late night trips to score, the lack of veins, the need for cash, all the bodily hunger for a drug, and with time ticking against a legal clock.

Tommy was arrested in Christmas 1979 for possession of heroin, but got off with a two-year suspended sentence. He tried methadone, but it simply prolonged the inevitable. In 1980, together with David Gapes, he was done for supply, selling three grams of morphine to an undercover police officer with a convincing story. Two and a half years. With another six months for allowing a club premises to be used for drug use.

On home-leave in 1982, he recorded ‘Morphine Blues’ at Mandrill Studios, It was released on Ripper Records, who piked out on the titling and called it ‘Mauveen’.

Aftermath

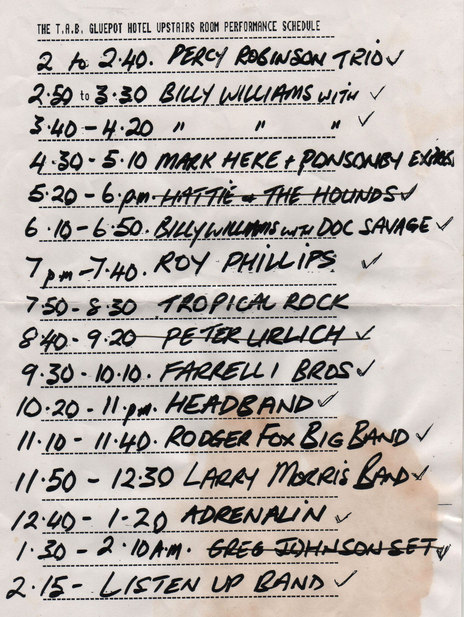

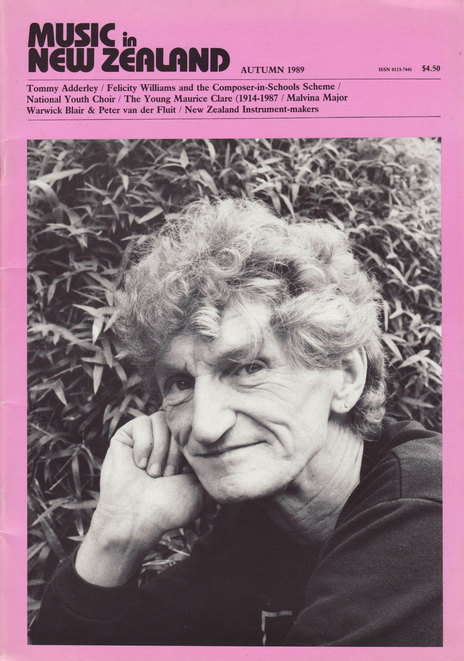

Tommy organised New Zealand’s first jazz and blues festival, the Auckland Jazz and Blues Festival in 1984, a second in 1985, two and a half days this time over Queen’s Birthday weekend, and more following. He clocked up hundreds of hours doing gigs for charities. He scored a residency at the London Bar on Queen Street, but somehow the heart was knocked out of him. His health suffered.

He helped create the Corner Bar at the Gluepot, but as soon as the place started making money, the breweries took back the contract. In February 1993, Tommy performed at the Gables, getting through one set before being found in the men’s in a pool of vomited blood. He died in North Shore Hospital on Friday February 5.

Unique, big-hearted, boundary-pushing, a magnet for people, a natural musician, host and organiser Tommy Adderley remains an under-appreciated figure of New Zealand music. He fought the law and the law won. But just as he’d started, he performed to the end.