Simultaneously, Levin toured countless overseas acts, from Ben E King in the 1960s to Bob Dylan in the 1980s. In his office above Durham Lane were posters for many of the other tours he had promoted: the Beach Boys, Rod Stewart, Elton John, Kiss, Buck Owens, Elvis Costello, Little Feat, Ry Cooder, Bo Diddley, Tom Jones, Lionel Richie, Cliff Richard … plus Randy Newman and Michael Jackson, whose proposed tours were both cancelled. The only other acts he seems to have missed out on were three who never came to New Zealand. All were flamboyant divas: Barbra Streisand, Bette Midler and Liza Minnelli.

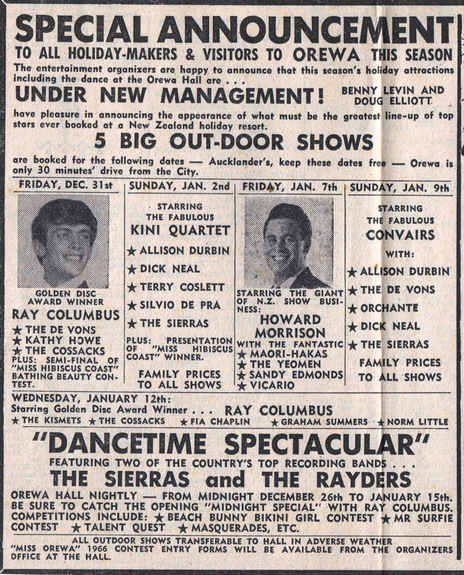

In John Berry’s 1964 book Seeing Stars – a slight but fascinating memoir of New Zealand show business – he recalls Levin taking a bath on a variety show he put on in 1960 at Auckland’s Carlaw Park (a venue that later tripped up other promoters such as Harry M Miller and Hugh Lynn). Top of the “Showcase of the Stars” bill were four minor “stars” from overseas, whose names meant little then, let alone now. Outside Auckland, the package tour went well, but at Carlaw Park the promoter’s “big mistake was in trying to ‘clean up’ with an outdoor performance,” wrote Berry.

“It was a gloomy night – not raining, but grey overhead. A chilly wind blew across the terraces. By the time the show was due to start, about 150 people were huddled together, and most of those were friends or associates of Benny’s, on the free list. While the entertainers battled against the outdoor acoustics, and with the rattle and whistle of trains passing close to the park, Benny stayed hopefully at the gates for almost an hour. Finally, carrying his leather money-bag which must have felt as light as a feather, he made his way slowly across the park. It was a sad moment.

“But to Benny, it was just another knock in a business that is full of them. Irrepressibly optimistic, he has gone on to other failures, and many successes, and will continue to promote entertainers for the rest of his life, because he is a born showman.”

The high-profile, high-stress life of a concert promoter gives many people the idea that it is a quick way to make a lot of money. Sometimes it is, but it’s also a quick way to lose a lot of money. A promoter needs to be well capitalised to sustain a big tour that bombs.

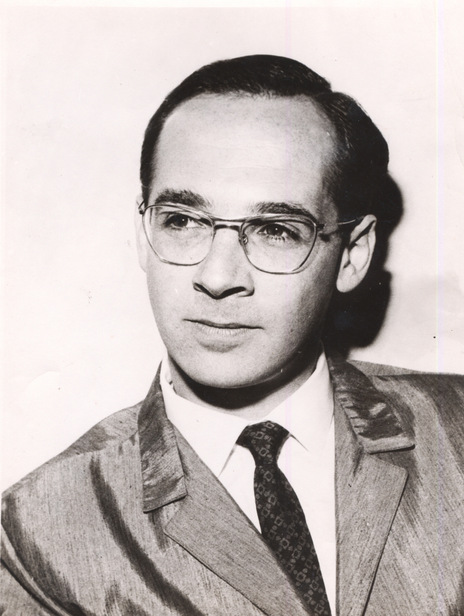

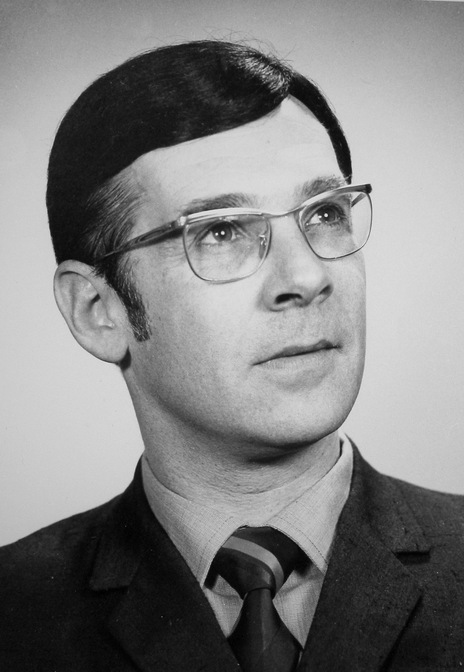

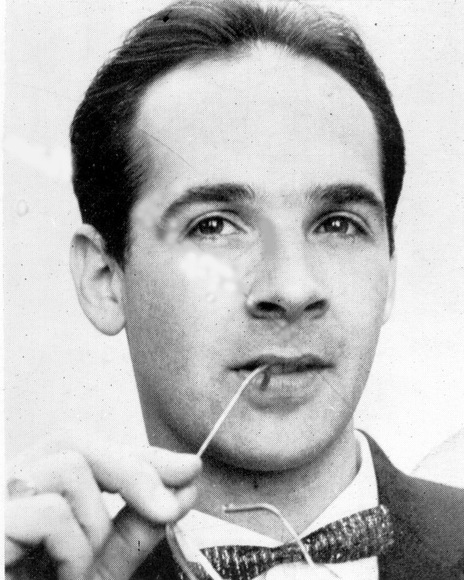

Levin was born in 1929, and grew up in Devonport. His parents met at a dance run by the Jewish community, of which they were both members. He enrolled in an accountancy course at Seddon Technical College, but left early to help support the family, as his father became unwell. So he struggled through a five-year apprenticeship as a clothing cutter at an uncle’s factory.

Music was his salvation. Levin was an avid listener to jazz programmes on 1YA, saved money to buy an old upright piano, and received lessons twice a week from a local teacher who was happy to teach popular as well as classical music. Levin totally immersed himself in his piano practice, encouraged by his parents. After his five-year apprenticeship was over, he tried working on the wharves, enduring the harsh conditions for about six months before returning to the clothing trade.

Levin formed a quartet, and they practised for 18 months in the family living room.

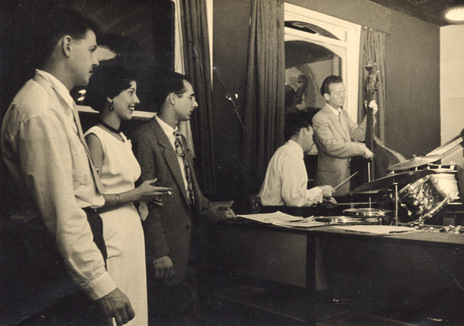

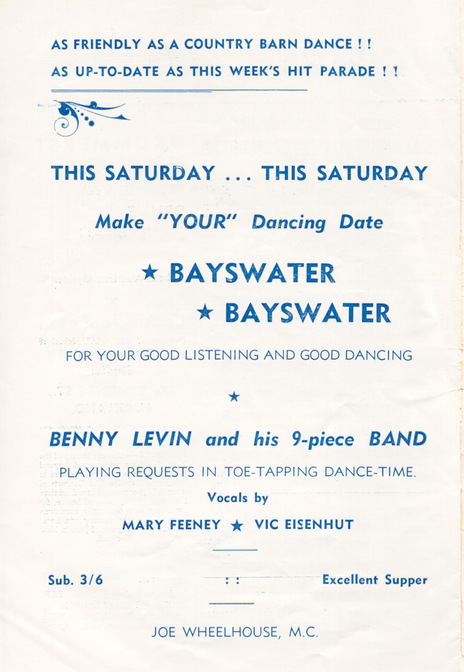

In his late teens Levin formed a quartet with some local friends, and they practised for 18 months in the family living room. Out of the blue a call came from Joe Wheelhouse at the Bayswater Boating Club on Auckland’s North Shore, who was looking for a new band. Benny “Dancetime” Levin and his Orchestra became the resident band; they stayed seven years at the venue, before moving over to St Seps in the city (near Khyber Pass) for another three years. Each night, they would attract about 600 dancers, who paid five shillings (50 cents) to get into the unlicensed venues, jive to the live band, then enjoy a supper of tea and cake. The Bayswater dances finished at 11.30pm so people could catch the last ferry back to Auckland.

The Dancetime band played stock big-band arrangements of current pop songs. Jock Nisbet wrote the band its own theme, ‘Dancing Time’, and Mary Feeney was the regular singer; there were also occasional big-name guests such as Mavis Rivers, Kahu Pineaha, guitarist Johnny Bradfield and pianist Nancy Harrie. Among the musicians who sat in when regular players couldn’t make it were Merv Thomas, Frank Gibson Jr and Murray Tanner. The band wore red jackets, black trousers and bowties. Levin himself was resplendent in one of his gaudy glitter jackets, and enjoyed doing a vocal turn singing rock’n’roll.

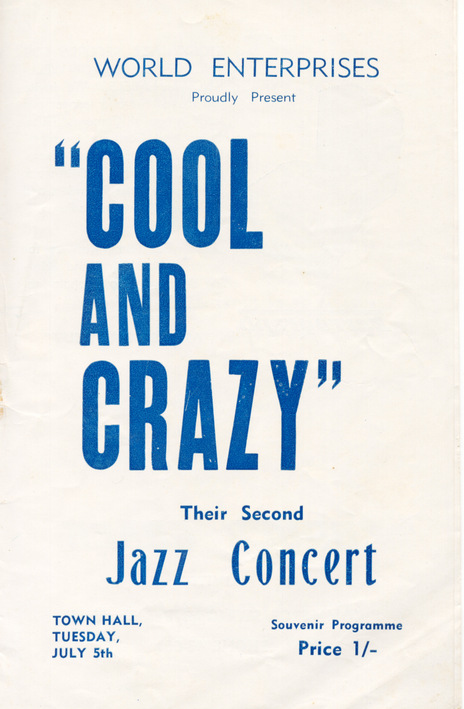

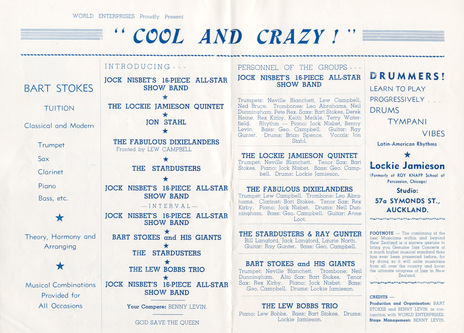

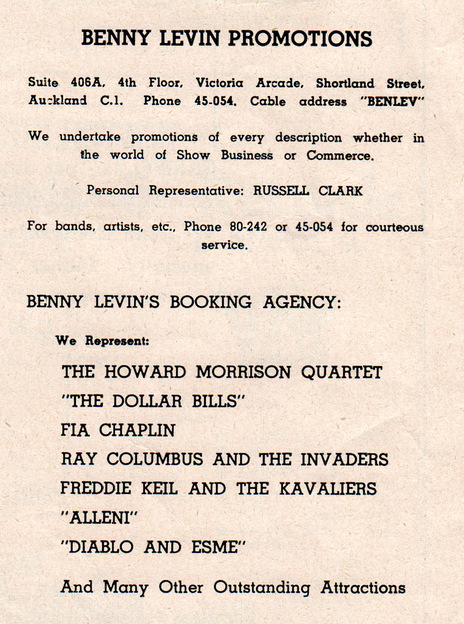

In the early 50s he started to run his own midweek dances, and this is how his promotion career began. It almost faltered immediately when trumpeter Bart Stokes gave him the misinformation that the South Island liked jazz – why not organise a tour there? Levin gathered together a stellar band for the 1952 This is Jazz tour: Stokes, Julian Lee, trumpeter Lynn Christie, and trombonist Dorsey Cameron. “With this first show, Benny learnt all the vicissitudes of large-scale promotion,” Beverley Simmons wrote in the short-lived Cinema, Stage and TV magazine. “He was everything: advance manager, publicity manager, front-of-house manager and compere, but he learnt enough from it to produce five more shows, tour them, cover costs and make a modest profit on each.”

Just as well, because the This is Jazz tour was a disaster. Forty years later, he recalled the tour to Toni McRae with a chortle. “Can you imagine the South Island in 1952 being terrific for jazz? We had a wonderful line-up of musicians and I booked the tour. We died on our backsides. But it taught me how to do it.”

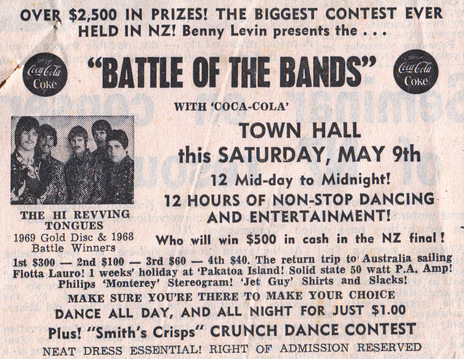

Levin’s promotional skills quickly came to the fore. In 1955, for example, he filled the Auckland Town Hall with 2,000 jazz fans even though interest in the genre had peaked and audiences were falling away. His eclectic, original approach is exemplified in a 1958 item in the Australian Music Maker, which wrote that Levin “has a new type of show lined up for the near future. It will consist of a monster dance, a treasure hunt with a car for first prize, a beauty contest and lots of entertainment with his own band, the Keil Isles, the Scorpions skiffle group, the Morrison Quartet and vocalist Austin Moon.”

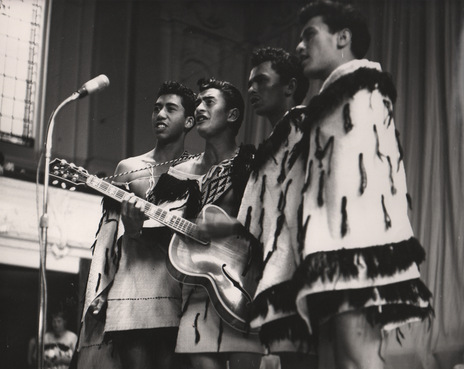

Among the many acts discovered by Levin, the biggest and most influential was the Howard Morrison Quartet.

Among the many acts discovered by Levin, the biggest and most influential was the Howard Morrison Quartet. He first saw them at Rotorua’s Ritz Hotel in 1956, and invited them to take part in a variety show in the Auckland Town Hall – the fee was £8, with no accommodation. Audiences and critics were excited by the Quartet’s harmonies and humour and the group quickly became a leading attraction in Auckland. Levin booked gigs ranging from cabarets to A&P shows to being the warm-up act for a jazz concert at the Town Hall. He also introduced the Quartet to Eldred Stebbing who recorded them in Rotorua on a portable Grundig tape-recorder. One of those first recordings became a hit, ‘Hoki Mai’ b/w ‘Po Kare Kare Ana’: soon the Quartet was the biggest draw card in New Zealand entertainment history.

Levin put an enormous amount of work into getting the Quartet established, however in 1959 a slick, ambitious promoter called Harry M Miller saw the group at the Colony restaurant, and approached Morrison with an offer to manage them. His timing was fortuitous. Levin – who knew Miller from childhood, when they attended Hebrew classes together – was tired, and had decided to quit the music business and buy into a takeaway bar. Levin encouraged Morrison to go with Miller, who promised the group £30 a week, whether they worked or not. “Take it,” he said. “You’d be crazy not to. And I gave away the whole thing at that time. Who was to know what was going to happen?”

Benny’s Tavern, on Victoria Street in central Auckland, “was a crazy idea,” said Levin, “but I made good hamburgers.” Unfortunately, the inner-city clientele was disappearing as factories and boarding houses closed down, and Levin’s health – and savings – suffered. After 10 exhausting months, he sold the business and was back as a promoter and dance-band leader.

Even before his break, Levin had showed an affinity with Māori entertainment, booking all- Māori shows that featured acts such as the Quartet, Eddie Howell, Hiria Moffat and the Sunbeams, a children’s band from Orakei (which featured Maurice Watene and Charlie Tumahai, future members of Herbs).

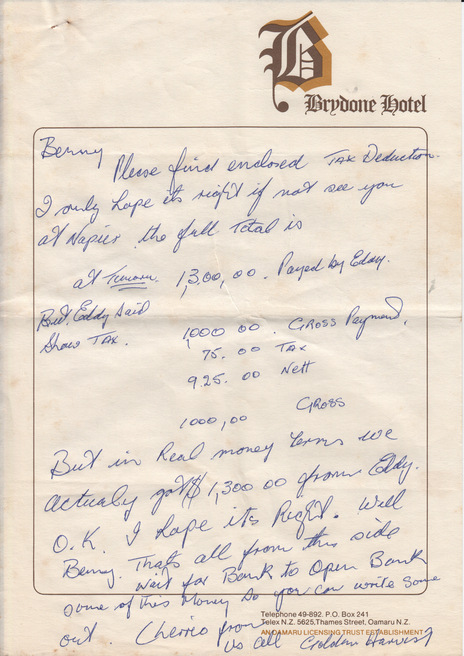

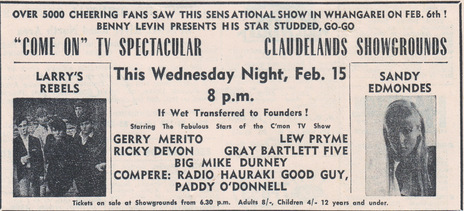

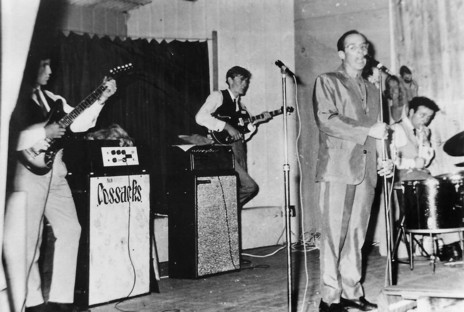

This continued from the 1960s – when he championed acts such as Howell (a singer in the Elvis mould, who never quite lived up to his potential as a new Devlin), Gerry Merito and Bunny Walters – to the 1980s, when he managed Golden Harvest.

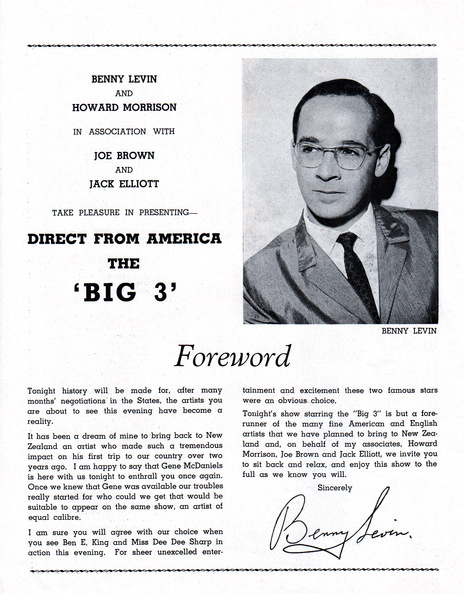

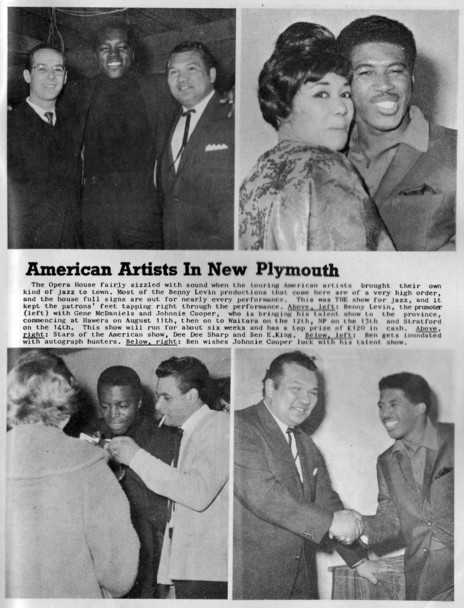

He booked tours big and small. In the provinces in the early 60s he toured a variety show featuring acts such as Peter Posa, Ray Woolf, “a girl vocalist” and a band led by Bob Paris. They would ask bus drivers to put up posters while driving their route, set up in tiny dance halls, use backstage toilets as dressing rooms, operate a small PA with a single microphone – and charge five shillings for a dance. In 1964 he toured the first show in New Zealand to feature a line-up of black Americans. He caught Ben E King between his time with the Drifters and his solo success, and billed them with Gene McDaniels and Dee Dee Sharp. Playing two shows a night, the production sold out throughout New Zealand.

Two memories of that tour stayed with Levin. “At Balclutha, Gene lost his voice and had to go to bed,” he recalled to Toni McRae. “I pleaded with him, sick as he was, to just come on stage in Dunedin the next night and let the audience see we weren’t pulling a rort. Well on he came in his shimmering suit and said in a whisper, ‘Hi everyone, I’m so sorry. I’ve lost my voice.’ They went wild. The show, with replacements, was mighty even with no Gene.”

Ben E King’s drummer – also black – ran out of white shirts to wear on stage, so Levin lent him one of his. “He was so overcome but I didn’t really understand why until two days later when he still hadn’t returned my shirt. ‘Oh Man’, he said, embarrassed when I asked him for it. ‘You wouldn’t want it after it’s been on my black body.’ I told him, ‘This is New Zealand, not America.’ A few weeks later on the streets of New York he was shot.”

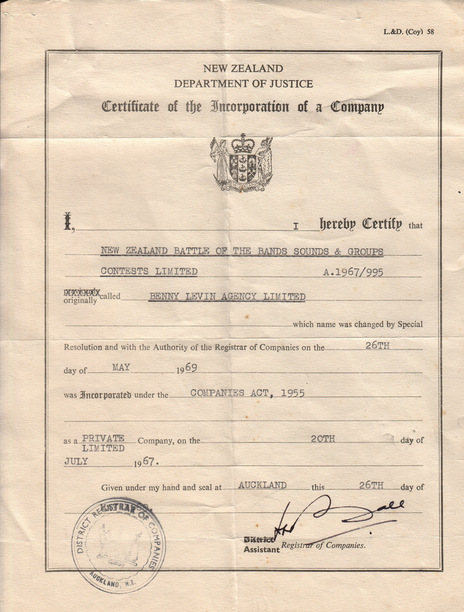

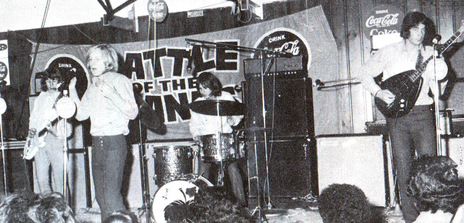

Levin founded his own record label, Impact, and in the first batch of releases were acts such as Larry’s Rebels, Lew Pryme, the In-Betweens and Ray Columbus. There was synergy with Stebbing and Phil Warren as Levin booked acts into their venues such as the Shiralee and the Monaco. The market set the fees: if a band such as Larry’s Rebels was in demand, it could earn between $500 to $1000 a night playing a club, or $2000 for a private gig. The gigs would draw up to 1000 people.

Overseas acts occupied much of Levin’s business in the 1970s.

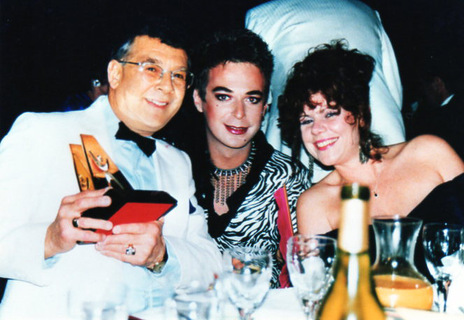

Overseas acts occupied much of Levin’s business in the 1970s. There were entertainers such as Sammy Davis Jr, Peter Ustinov and comedian Dave Allen. Among the musicians were Elton John, “a temperamental genius” who, at lunch with Levin, asked for hamburgers and Dom Perignon. Lou Reed was miffed when a Christchurch bouncer denied him entrance to a nightclub, so the next day he refused to perform unless the perpetrator was sacked. Levin discreetly arranged for the bouncer to take a paid night off, and told Reed what he wanted to hear. Rod Stewart famously snatched Levin’s toupee off his head, and soon it was being passed around the restaurant on a sliver platter; someone lit a match and tossed it on the platter and the toupee went up in flames. “Rod was mortified,” recalled Levin. “He offered to pay for another wig.”

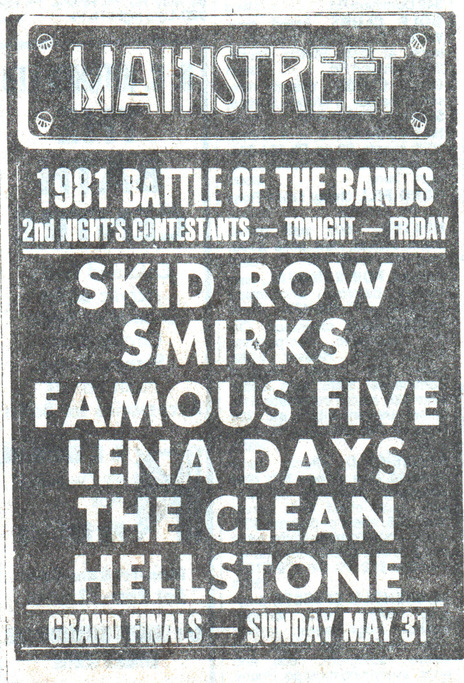

But his commitment to local acts never stopped; from the late 1970s he was a partner in New Music Management which booked bands playing original music into pubs. Besides his toupee, his loud jackets and his poor driving, what Levin was most famous for was keeping his word. After Levin died from cancer in 1993, Howard Morrison recalled to the NZ Herald’s Peter Calder, “You knew that, whatever happened, if Benny said you were going to get paid, you were going to get paid.”

Levin was frugal, to the artists’ benefit. Morrison joked that his careful budgets were “so tight he wouldn’t let the draught under the door.” While Levin may have been generous with his gifts, he didn’t go in for a flashy lifestyle. The NMM offices were drab, and he lived in a two-bedroom unit in Papatoetoe. “Money never meant a lot to me,” he told Calder three days before he died. “I never wanted to drive a Rolls-Royce and own a mansion. I am very happy with what I have done in life.”

Of all the queens of show business Levin worked with, a special memory was the time he was invited to go to a cocktail party on board the royal yacht Britannia. “I couldn’t believe it,” he told Toni McRae. “It may be because I’d arranged a concert here for Prince Charles and Princess Anne. Anyway I took my mum Katie who wore a tiara and looked lovely. Suddenly there was the Queen herself, offering us sausage rolls and savouries on a silver tray and asking me, “And what do you do?” Very few did more to support New Zealand music than Benny “Dancetime” Levin.