AudioCulture

The noisy library of New Zealand music

Te pātaka korihi o ngā puoro o Aotearoa

Tony Littlejohn

aka Littlejohn

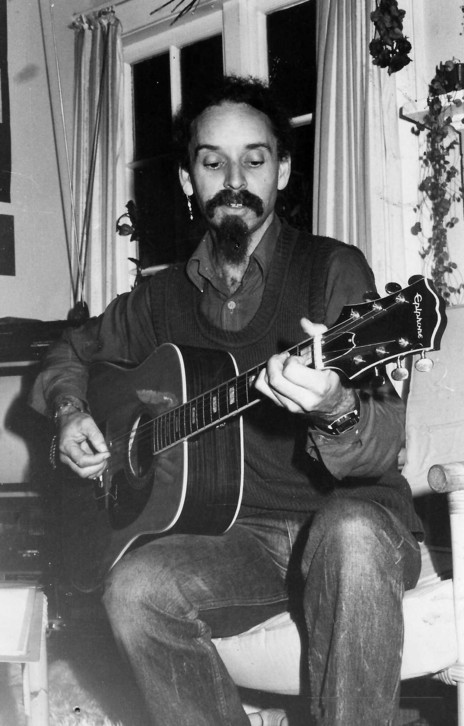

Littlejohn grew up in Rotorua, where he picked up a few chords from his mother on ukulele. He picked up the rest from listening to older friends who at the time were playing Shadows and Peter Posa instrumentals.

By the age of 14 he was playing professionally, his career kickstarted by escaping out his bedroom window after the evening meal and after his father had gone to bed ahead of a 3am logging run from Kawerau to Gisborne.

He would take his guitar and meet with older friends to play clandestine parties and underground socials after 6pm closing of the pubs, which “paid very well”.

They played jazz and hit parade songs with Littlejohn equally as adept on bass as guitar and vocals.

His first band The Knights started out playing instrumentals. After winning a beach talent quest they graduated to 21st and wedding celebrations. They played jazz and hit parade songs with Littlejohn equally as adept on bass as guitar and vocals.

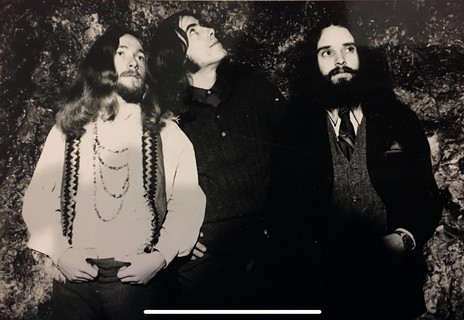

With the arrival of The Beatles, The Rolling Stones and psychedelic music, the trio changed their name to Internal Crocodile, mimicking some of their music idols with long hair and suits.

The band, featuring Don Bedgegood on lead guitar and vocals, Larry Abbott on drums and vocals and Littlejohn on bass and vocals, changed its name again to Soul Movement then simply The Movement.

Songwriting soulmates

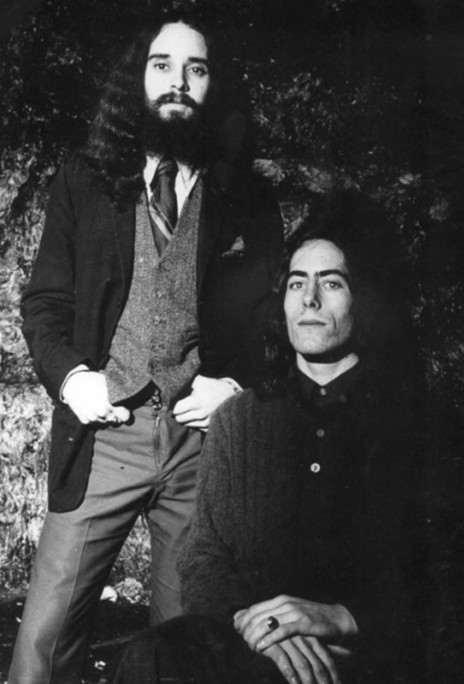

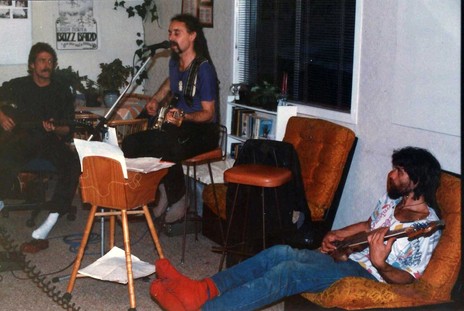

The Movement, allegedly the only professional rock unit in the region, had already begun to experiment with their own original compositions, mostly written by Littlejohn. But a 1968 collaboration with multi-instrumentalist and singer Corben Simpson changed the direction of both their careers.

Simpson began playing guitar at aged 14 in his hometown of Manurewa, and after trying his hand as an apprentice electrician, moved to Tauranga in 1968 to play bass and sing with four-piece group Sons and Lovers, comprising Alan Moon on keyboards, Ally Mathews on drums and Denny Price on vocals.

He remained with them until shortly after they won a Waikato-Bay of Plenty Battle of the Bands semi-final. He urged the band to move to Wellington to follow up on their success but they were reluctant.

Simpson moved to Hamilton to be with his girlfriend Barbara Vail working three nights playing bass with a resident backing group at the Hillcrest Lodge and three nights at the Starlight Ballroom where he began building a reputation as a singer.

He purchased new equipment, including one of the first electronic drum machines in the country and began appearing at Sunday afternoon lakeside “Happenings” in Hamilton, organised by Larry Abbott, the leader of The Movement.

Movement bass player Tony Littlejohn asked Simpson to perform at his birthday party. Before long there was a close friendship and he moved into Littlejohn’s flat.

The management at the Hillcrest weren’t happy that Simpson kept singing sad songs and “making the women cry and go home without spending any money ... They wanted me to play ‘Ten Guitars’ rather than ‘By The Time I Get To Phoenix’.”

Beyond the ballads

It was this curb on Simpson’s repertoire and the fact the battery kept running out on his electronic drummer that encouraged him to accept an invitation to join the big rock sound of The Movement in late 1968 on rhythm guitar and vocals.

Here was a chance to sing Led Zeppelin, Jimi Hendrix and hard rock, something the Hillcrest would never have tolerated. “His voice was so good I stepped back from lead vocals and we worked on harmonies together,” says Littlejohn.

The Movement went to win the Waikato Battle of the Bands and came third in the national finals in Auckland.

The day after Simpson married Barbara, on 26 September 1970, the couple moved to Rotorua where he joined keyboard player Murray Hancox’ band Captain Fogpocket on rhythm guitar and vocals.

In September 1971 he rejoined The Movement as they headed to Wellington and quickly picked up work at clubs, concerts and dances. Guitarist Bedgegood didn’t stay long, moving back to Waikato, followed closely by drummer Larry Abbott and his girlfriend.

They had quit in the midst of a string of gigs. Littlejohn and Simpson were in a fix: while they could turn in a credible performance as a duo most of their bookings were as a rock unit.

Bruno in the band

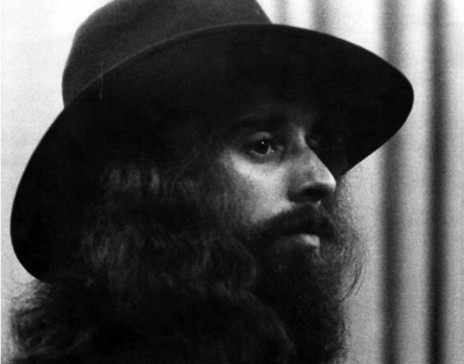

It was then that a friend put them in touch with Bruno Lawrence, who’d been playing professionally for 13 years, most recently in the drum seat with The Quincy Conserve.

“He was unlike anyone I have every met or played with before. He’d been involved in an acting job and turned up with a shaved head, a colonel’s hat, a white shirt, bow tie, shorts and bare feet. The crowd just parted when he walked in – he looked so strange,” says Littlejohn.

“He just walked in and without any rehearsals, picked up the drumsticks and played like he knew all our songs. I learned a lot from him including how to lead a band and how to handle people.”

Lawrence stayed with The Movement to fulfil the jobs they’d booked. Louise Warren in the Sunday Times, 12 September 1971, caught their act at Lucifers. “It’s unusual to find a young pop musician singing jazz on the side and Corben doesn’t really fit the image ‘til he opens his mouth and sings. He attributes his interesting jazz to Ronnie Smith ‘one of the best and most respected jazz pianists in the country’.”

The Movement were soon joined by guitarist Kemp Tuirirangi and organ player Alan Moon from Simpson’s old band Sons and Lovers.

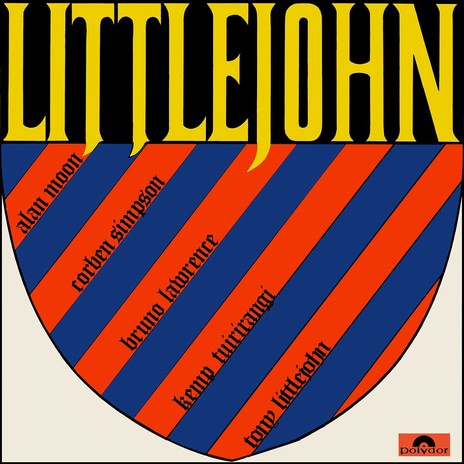

“We made an album under the name The Movement but just before they were about to release it they told us we had to change the name straight away because someone else had the name Movement. I suggested Littlejohn,” says Simpson.

They released a single on Zodiac called ‘Dead And Gone’ backed by ‘Turning On To Rock ‘n Roll’, before moving to Alan Dunnage’s Sonic Label to record three more singles, ‘Everybody Knows’ b/w ‘Social Smoker’; ‘Have You Heard A Man Cry’ b/w ‘Nice and Easy’; and a third, ‘Why Did You Leave Me’ b/w ‘Bloodsucker’. Littlejohn and Simpson shared vocals.

Collaborating with Corben

‘Have You Heard A Man Cry’ was written in 1970 at a low point in Simpson’s life, when he had a row with Barbara and broke off their engagement. They were back together in a couple of weeks but the song rode up the Top 20 nationally and reached No.13 in Wellington, eventually winning him the 1971 APRA Silver Scroll.

In 1971 Simpson released two singles on the Strange label, owned by his manager Edd Morris under the pseudonym Girven O’Strange. On the first, a cover of Van Morrison’s ‘Moondance’ was on the A-side, backed by the Gerry Goffin and Carole King penned ‘Up On The Roof’. Gershwin’s ‘Summertime’ was backed by ‘Jean’ (from the movie The Prime Of Miss Jean Brodie) on the second single and both were included on his first self-titled album released in 1972.

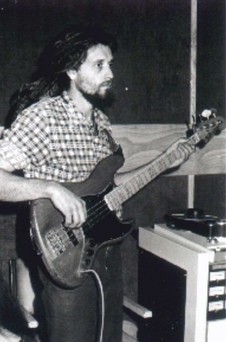

Tony Littlejohn was on bass, Bruno Lawrence was on drums with Alan Moon on Hammond organ and Michael LePetit on piano. Corben Simpson played acoustic guitar, pouring out his soul with haunting vocals. Desna Sisarich was on background vocals and the cover was designed by Dick Frizzell.

Concurrently the Littlejohn band was recording further tracks at Sonic Studios for their self-titled album (Littlejohn, Polydor). After this album, Chris Seresin, a friend of Bruno’s who’d been in Fresh Air, was invited to join the unit on second keyboard.

Littlejohn increasingly became more involved with the film side and began to incorporate theatrics and props, lighting and a menagerie of weird ideas into their act.

Bruno Lawrence had his own ideas to push social, musical and creative boundaries. Much of the inspiration came from his association with moviemaker Geoff Murphy and their sideline business the ACME Sausage Company, which had produced an experimental musical called Santa’s Liquid Dream.

Littlejohn increasingly became more involved with the film side and began to incorporate theatrics and props, lighting and a menagerie of weird ideas into their act. Soon it was time for a new name.

“We were sitting around discussing a job offer to play on a ship bound for England when photographer Helen Whitford just ‘blerted it out’. Bruno then came up with the name BLERTA and she spontaneously came up with the meaning, Bruno Lawrence’s Electric Revelation Traveling Apparatus,” says Littlejohn.

There have been several explanations from Bruno Lawrence and Geoff Murphy as to how the name came about although Corben Simpson insists he first coined it.

BLERTA breaks through

Bruno added another dozen or so talented friends and associates, including musicians, actors, clowns, lighting specialists, writers and photographers with a view to presenting “kids shows” around the country and generally giving people a cultural shock.

Littlejohn would play their music and Corben would perform solo as would guest vocalist Beverley Morrison (Beaver). They’d perform dramatic productions, show films already created by Geoff Murphy and Bruno (who had won the 1970 Feltex actor of the year award) and film and record everything they did along the way for later use.

Once the plan was hatched and the enthusiasm of the team was tapped the group paid $400 for the former Wellington City Council 1948 Leyland Tiger bus, which had belonged to Sons and Lovers.

Alan Moon was the only one who could handle the temperamental transport so he became designated driver. Littlejohn’s Jaguar and another five cars were added to the convoy. BLERTA’s unique multimedia potpourri was on the road.

At its peak BLERTA embraced an entourage of 25, including nine musicians, technicians, Pete Pharazyn’s lightshow, Corben and Barbara, Bruno’s wife Veronica, their four children and her sister Pat, and Geoff Murphy’s wife and their four children.

Perhaps the biggest crowds they drew were in Nelson where up to 700 people attended their shows. As they travelled about the ideas developed, the jam sessions gave rise to new songs and the lighting and projection equipment was housed in a home built unit patterned after the lunar module.

Through the musical jam sessions ideas for songs evolved, including the New Zealand classic ‘Dance all Around the World’ written by Simpson and Geoff Murphy with a voiceover by Bill Stalker, based on Margaret Mahy’s children’s story The Procession.

The single entered the charts in May 1972 and stayed there for five weeks, reaching No.13 on the Singles Chart. The BLERTA sessions were engineered at EMI studios in Wellington by Michael Grafton-Green and produced by Peter Dawkins.

Change is in the air

By March 1972 BLERTA was working its way up the North Island with stopovers in every “major, minor and one-horse town” from Wellington, through Wairarapa, Horowhenua, Manawatu and Hawkes Bay and on up to Whangarei.

On many occasions it looked as though the whole thing was falling apart. Musicians left and revisited and there were rumours it had all turned to custard but somehow Bruno’s enthusiasm would rally the troupe and they’d carry on again.

Simpson was featured as a solo artist throughout although he continued to fulfil solo commitments. The Littlejohn album was finally released eight months after it was recorded.

The BLERTA line-up continued to change. Kemp Tuirirangi and Tony Littlejohn left and were replaced by Chaz Burke-Kennedy and George Barris (The Underdogs, Jigsaw) and actor Bill Stalker was joined by his peers Tony Barry and Ian Watkin. Corben Simpson remained a part-timer, heading off to do his own thing including working with Anteapot, the group that was to become Dragon.

Littlejohn describes his time with BLERTA as an amazing experience.

Littlejohn describes his time with BLERTA as an amazing experience. “People didn’t know what to think. We’d get met by police and stopped by road blocks but everywhere we went we’d always win the town over. They must have thought we were a gang or something – we nearly got run out of a couple of towns but the children’s shows always softened their hearts.”

Tony Littlejohn moved to Sydney where in 1973 he reformed the Littlejohn Band playing jazz-rock fusion material with mainly New Zealand musicians including Scratch Rae from former Waikato bands The Nomads and Sons and Lovers, Mina Motu on drums and bass, and various other players including members of Tokoroa’s Collision.

When BLERTA came across to Sydney he occasionally gigged with them and with Corben Simpson when he visited.

Radical reggae transformation

The time across the Tasman was plagued with tragedy. A member of Littlejohn’s road crew and a bass player named Terry from Whanganui both died from a drug overdose. Tony was opposed to the use of hard drugs and devastated by the loss.

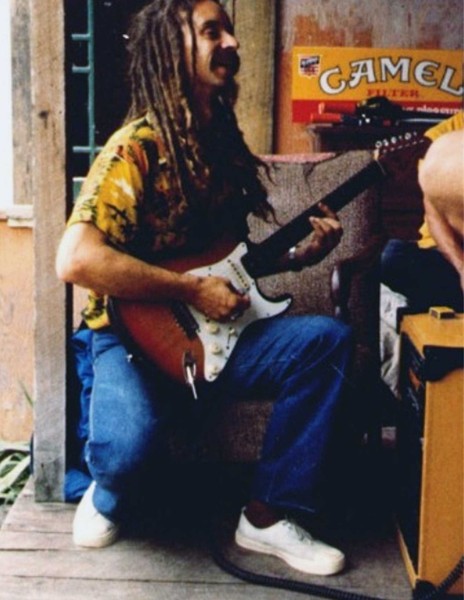

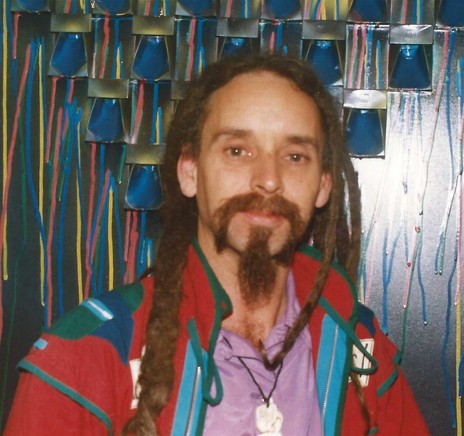

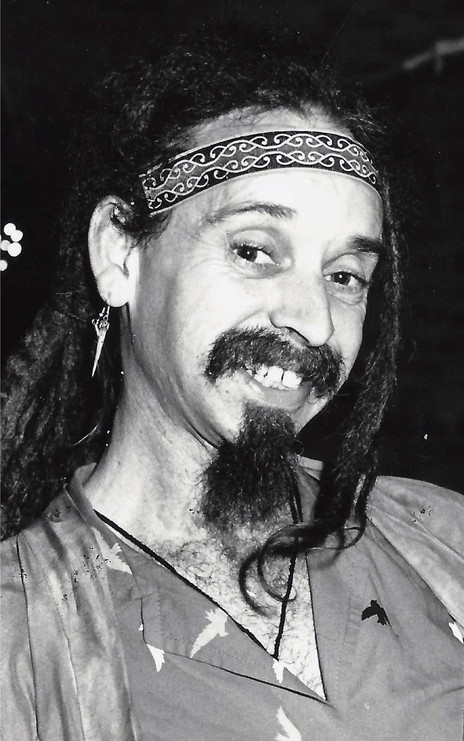

In 1976 he stepped into roots music, growing his trademark dreadlocks, picking up heavily on the Bob Marley influence and forming the first of his Ghetto bands. The style of music appealed even though it was very early days for reggae he was motivated by the social justice elements.

He found it hard finding the right musicians and when he did found few venues would book a reggae band and that having dreadlocks actually alienated the Danish-Māori boy from New Zealand. He often found himself facing the brunt of racial slurs.

Ghetto ran and promoted its own concerts and on discovering few bands were interested in playing pubs in the rougher Sydney suburbs like Redfern, they stepped up and were made welcome among the mainly Aboriginal regulars.

On Australia Day he played a concert for hundreds of Aboriginals and wrote ‘Let Your Body Move’ for the Aboriginal Women’s Centre, which worked to dry out alcoholics and look after women and children facing difficult times.

“I also wrote ‘I & I Talkin’ ... one law for the rich, one law for the poor ... at that time to highlight what I saw happening there. Not a lot has changed.”

Littlejohn says the arrival of Bob Marley in Sydney in 1979 changed the attitude of many people toward reggae.

Littlejohn says the arrival of Bob Marley in Sydney in 1979 changed the attitude of many people toward reggae and Ghetto found itself getting much more work in Melbourne and Sydney. Highlights were playing support for Midnight Oil, The Angels and the Doug Parkinson Band.

He found it “a dangerous time ... you’d be walking down the street and people would jump on you and try and rip out your dreads so I went and did martial arts and then moved to Nimbin to rethink everything, wrote some more songs and planned to come home to New Zealand.”

Ghetto pioneers Kiwi reggae

He returned to New Zealand in 1980 and teamed up with his brother Terrence on bass and drummer Lloyd Lattimer on drums, keeping the Ghetto name alive and playing a hard-edged funk-reggae mix including a growing number of originals.

“It was still fairly early days for reggae. We were playing it before Herbs hit the mainstream but they had really good management and got the profile and recognition.”

In 1985 Corben Simpson attempted a comeback under the guidance of Terence O’Neill Joyce of Ode Records with a re-recording of ‘Have You Heard A Man Cry’. The song won the APRA Silver Scroll in 1971 and was chosen again in 1975 as the best New Zealand composition of the previous 10 years.

Simpson adjusted the lyrics to take more of the blame for the demise of the relationship with ex-wife Barbara. He called his old friend Tony Littlejohn into Mandrill Studios to play some new guitar lines, added drummer Bud Hooper and the vocal capabilities of Mahia Blackmore and Janice Leaf from Meg & the Fones.

Simpson wasn’t entirely happy with the re-release and resisted efforts to promote it, fading again from the scene, appearing sporadically at hippie gatherings around the country, often as part of the Gypsy house trucker’s band, in a duo with Blackmore, playing alongside his old mate Sonny Day or with Human Instinct drummer Maurice Greer.

By 1985, Tony Littlejohn’s Ghetto had evolved into Heartwarrior, with a constantly changing line-up that mostly featured his former wife Mina Paikea on supporting vocals, brother Terence on bass and Lloyd Latimer on drums, performing concerts and gigs in Auckland, at Rātana Pā and around the country.

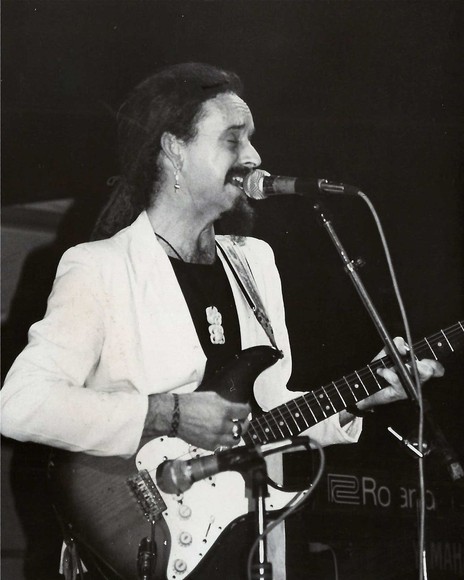

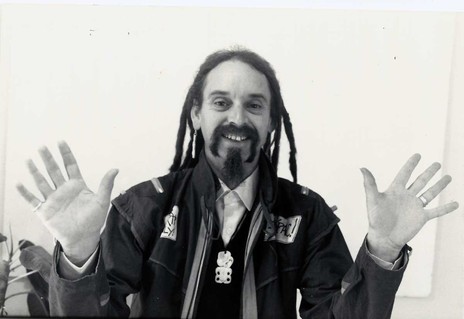

He then reverted back to the Littlejohn name with further line-up changes, often adding former Billy TK bass player Gav Collinge on second guitar, and playing regularly around Auckland traps at concerts and in the Far North.

A vehicle for true stories

Littlejohn says reggae was a great vehicle for expressing ideas about his growing spiritual awareness, the Gospel message, issues of social concern and true life stories.

A number of his songs put music to other people’s poetry. His mother wrote the lyrics in ‘True Friends’ and his powerful cover of Billy TK’s ‘Prisoner’ came out of a collaboration in the 1980s.

“Like so many songs the same theme gets repeated, there’s so much corruption, so many people are in poverty and in jail and you don’t even have to be in jail to be a prisoner,” he says.

“You have to find freedom – as Marley says, ‘release yourself from mental slavery’ – no matter how much the system tries to crush you in the end, love is the only answer.”

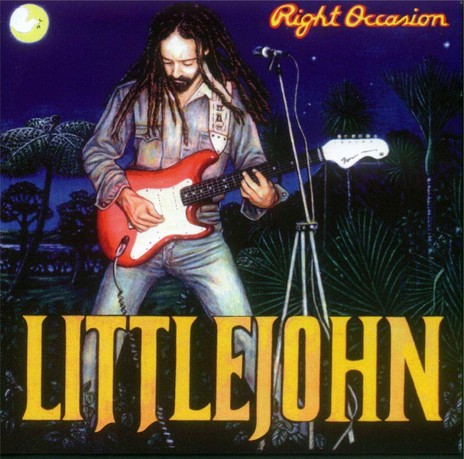

Some of the dozens of songs written by Tony Littlejohn were included on double cassette Right Occasion, recorded over a range of sessions at Mandrill Studios in early 1993 and upgraded to a double CD with 21 tracks, recorded at Scoop de Loop and Pryde Studios in Palmerston North and finally released in 2000.

Tony Littlejohn continues to put together various cover bands and write new material, recording when the right occasion calls for it. He’s also enjoyed watching his two sons Tawhiri (drums) and Raniera (bass) carry on the family name as a sought-after rhythm section in Soljah and playing and recording with other top names.

Visit our sister site

NZ On ScreenMade with funding from

NZ On Air