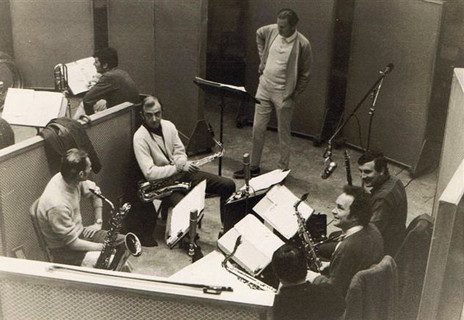

Likewise, although his time in Sydney was brief, top Australian jazzmen Bob Bertles, Don Burrows, Bernie McGann and Jimmie Sloggett, a lifelong friend, have all sung Gillett’s praises. Big band leader Bernie Allen, who provided Gillett with his first New Zealand gigs, said of him, “He was a renegade, the sort of individual talent which we all aspire to.”

Despite the accolades and the influence he exerted, Bob Gillett, who died in 2013, remains largely unknown.

Robert Allan Gillett was born in Santa Ana, California on 26 March 1925, claiming an exotic blend of French, Scots and Navajo blood. At an early age he was an accomplished musician on several instruments before concentrating on the clarinet and, later, the alto saxophone, which was to remain his preferred instrument. At age 18 he gravitated to Los Angeles, auditioning for one band leader who told him that he sounded “too black”.

“I didn’t know what he meant by that at the time, although I never did much like Benny Goodman and Glenn Miller,” he told me in 1991. “My personal tastes ran to the big bands of Count Basie, Duke Ellington and, in particular, Jimmy Lunceford.”

With the world at war, Gillett was soon conscripted into the army which, given his natural rebellious nature, was always going to create problems. His two years of military experience, such as it was, was filled with friction and clashes with authority, including a mandatory psychiatric appraisal. “They thought I was mad,” Gillett remembered, “but I was just pissed [off].”

In 1944 Gillett was shipped to Europe, where he persuaded his superiors that he would serve his country better as a bandleader. No one ever accused Bob Gillett of false modesty and he was soon arranging and conducting an 18-piece officers club band.

It was the improvisational nature of jazz which appealed most and he spent the 1950s largely as a journeyman musician.

After the war, Gillett took full advantage of the G.I. Bill to further his musical aspirations, studying classical composition under Arnold Schoenberg. In 1953, Gillett’s Sonata For Small Orchestra was performed by the Los Angeles Chamber Symphony Orchestra.

Despite his lifelong interest in classical composition, it was the improvisational nature of jazz which appealed most and he spent the 1950s largely as a journeyman musician, only a two-year spell with the Stan Kenton Orchestra providing stability. He played behind Billie Holiday in Milwaukee (“she chose me as a playmate,” he told Keith Newman in 2007) and toured with Ella Fitzgerald. In Palm Springs he was sacked by Frank Sinatra and roughed up by his minders. Other notables he played alongside included Stan Getz, Art Pepper and Anita O’Day.

In 1959, very much inspired by the “beat” writers and poets, Gillett set his sights on India, planning to country-hop to his ultimate destination. He never got there and a six-month jaunt across the Pacific in a two-man boat saw him land in Sydney in February 1960.

Although he was to secure bookings in Sydney recording studios and radio shows, Gillett felt most at home in the city’s jazz clubs, notably El Rocco. Over the previous 12 months Sydney had been invaded by a large number of NZ musicians. Drummer Tony Hopkins and keyboardist Claude Papesch arrived in May 1959 as members of Johnny Devlin’s Devils but soon ditched rock and roll for jazz. Other New Zealanders to arrive included guitarist Bob Paris, saxophonist Brian Smith, pianists Judy Bailey, Dave MacRae, Mike Nock and Mike Walker, bassists Andy Brown and Rick Laird, and drummers Frank Gibson Jr and Barry Woods. Some would soon return home, some would join the vanguard of jazz in Sydney; most had some sort of contact with Bob Gillett.

In late 1960 Gillett arrived in New Zealand, chasing work and immediately impressing radio bandleader Bernie Allen. It wasn’t long before he was arranging his own radio band, his bread-and-butter over the next five years. In 1962, reunited with Tony Hopkins, he became part of Hopkins’ jazz workshops at the Bali Hai Coffee Bar. In 2011 Hopkins told me, “There were two streams in Auckland jazz: the established radio band clique and younger players interested in innovation and musical risk-taking. Bob was cutting edge, the best alto player I ever played with. His lines could bring you to tears.”

In 1962 the Bob Gillett Sextet supported the Dave Brubeck Quartet on a national tour. Gillett wasn’t impressed. “He played too many notes,” he told me 30 years later.

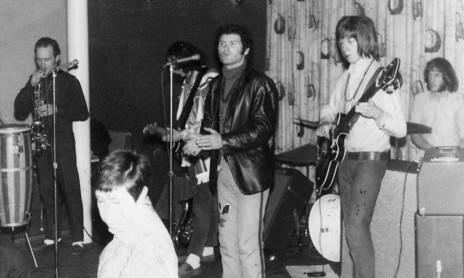

Throughout the 1960s Gillett became increasingly interested in rock music, incorporating rock musicians in his radio bands, notably guitarist Doug Jerebine. Featured vocalists included Tommy Ferguson and Ray Woolf. In 1965 he formed Bob Gillett & The Blue Blades to perform at Auckland nightclubs. Musicians who passed through included Jerebine, bassist John “Yuk” Harrison and organist Claude Papesch.

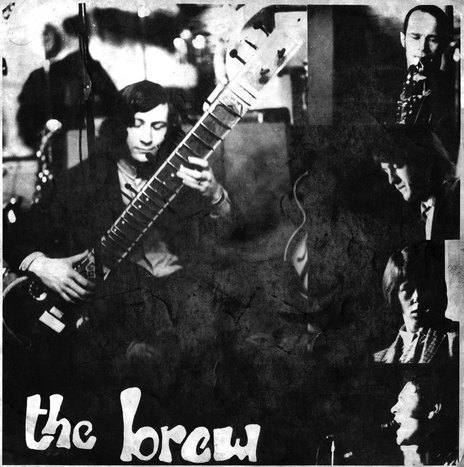

In 1966 Gillett heard that the NZ Tea Council was planning a promotion aimed at teenagers and successfully pitched an idea. The result was a series of nationwide performances and a radio promotion built around a radical arrangement of the jazz chestnut ‘Tea For Two’, sung by Ferguson. Featuring Gillett, Ferguson, Jerebine, bassist Puni Solomon and drummer Trix Willoughby, Gillett named the band The Brew. They released just one single, ‘Bengal Tiger’ (vocals by Ray Woolf) with ‘Tea For Two’ on the flip side. Ray Woolf remembers, “Andy Shackleton [drummer][and I were asked to join but decided our band (the Auckland Avengers] was going pretty good and these guys were a bit out there, so we declined.”

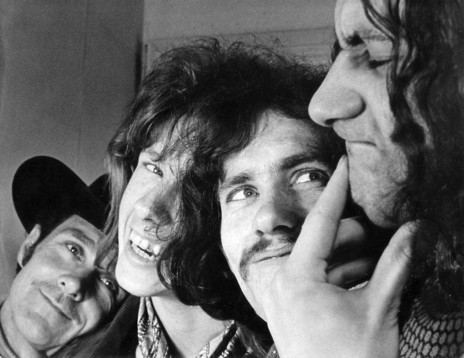

Ray Woolf wasn’t the only one who thought that The Brew was “a bit out there” and regular gigs were hard to come by. Gillett, now in his 40s, seemed out of place in teenage venues and the band’s music was, well, “a bit out there,” featuring Gillett’s amplified sax, Jerebine’s feedback-laden guitar virtuosity and Trix Willoughby’s odd drum kit (including pots, pans and dustbin lids). The band’s repertoire was mostly contemporary covers (Spencer Davis Group, Monkees, even Herman’s Hermits), although barely recognisable given the new treatment.

The Brew went through numerous line-up changes, with Gillett and Jerebine the only constants.

The Brew went through numerous line-up changes, with Gillett and Jerebine the only constants (guitarist Harvey Mann and singer Archie Bowie were in the latter-day line-up; at one stage Gillett played drums). They scored an unlikely residency at The Picasso, a former jazz venue whose new owners catered to Auckland’s street gangs and underworld fraternity. One night Gillett, never known to hold his tongue, was knocked unconscious by a well-known criminal. Although, by and large, The Brew fitted in quite well.

In late 1967, at Gillett’s instigation, a union was formed with other Auckland bands in an attempt to gain larger fees for nightclub acts. Club owners responded by banishing The Brew, who found themselves unemployable, leading to the other bands quickly dropping the pact and The Brew’s inevitable demise.

By 1970 the radio band era had come to a close and jazz had been all but eclipsed by rock music. Gillett survived with session and production work (The Chicks, Ray Columbus, The Rumour). In 1970 he formed Breeze with Sonny Day and produced The Underdogs album Wasting Our Time, becoming angered by budget restraints that saw the album released before he could add his saxophone parts. In 1971 he was a part-time member of Space Farm with Harvey Mann, Billy Williams and Glen Absolum. Bob Gillett appears on their self-titled album, but by the time it was released in 1972, he was back in the USA.

His visit there was intended as an extended vacation with family but visa problems prohibited his return to New Zealand. Despite on-going legal representations, petitions to NZ Immigration and the support of industry heavyweights Eldred Stebbing and Phil Warren, it was 20 years before Bob Gillett again set foot in his adopted homeland. He returned in 1991 and settled on Waiheke Island. Following extensive dental work he didn’t feel comfortable or confident playing the saxophone, and he replaced that passion with short stories and beat poetry. In 2003 Gillett’s Sonata For Small Orchestra was performed by the Auckland Philharmonia Orchestra.

Bob Gillett, one of the genuinely unsung heroes of NZ music, died on 9 November 2013. Doug Jerebine said, “Bob was the master of us all and no one plays the master except the master; his type of knowledge is restricted to the saints.”