Alan Galbraith was born in Luton in the UK and raised in Richmond, Nelson. He was given his first guitar at age 12 by his parents, which led to his first band, The Dynamics, who played local dances in his high school years. Shortly after leaving school, Galbraith was asked to join one of the key bands in the region, The Silhouettes, which was quite a step up.

“They were quite a bit older than me – they were great musicians and I was just a 17-year-old sort of stars-in-your-eyes guy. Playing with these guys was amazing. I learned so much really quickly.”

The Silhouettes (L to r: Ian Mills, Alan Galbraith, Gary Stewart, Dick Brough) 1964 - Alan Galbraith collection

Silhouettes to Sounds

The young Alan Galbraith’s aspirations went beyond local dances, however. “I had my eyes set on being a pop star, they were married and had children. I was also inspired by Brian Peacock, the bass player from a group called The Bel-Airs in Nelson who had joined The Librettos in Wellington, and then went to Australia to play with Normie Rowe’s Playboys and, later, Procession. Brian was a friend of mine … a kind of a hero … and I thought if Brian can do this I can. So I sort of followed his footsteps.”

The Silhouettes split in late 1965 and Alan found himself doing solo shows at several Ken Cooper promoted gigs, supporting the likes of The Librettos and The Breakaways. Impressed by what he was seeing, in 1966 Cooper, one of the top promotors in the Wellington region, asked Galbraith to cross Cook Strait and join a band he managed, Sounds Unlimited. A Palmerston North combo which had shifted to the capital, they had just lost their lead singer, Bogdan Kominowski, to a solo career (as Mr Lee Grant).

Five decades on, Galbraith still questions his teenage life-changing decision. “I was a guitar player and not a singer. I had never really fronted a band as a singer before so why on earth I was fronting this band – and as a singer, I have no idea.”

Galbraith joined Sounds Unlimited in May 1966. Like many bands in the Wellington live scene, Sounds Unlimited recorded for the locally based His Master’s Voice label, with three singles released in 1966 and 1967. Galbraith gigged solidly with them until the end of 1966 when he was hospitalised with nodules on his vocal chords. Recovering, Ken Cooper suggested that Sounds Unlimited re-group and head to the UK, where expat New Zealander John Hartnett was running a club called The Tiles Club. The deal was that the band would travel to Britain on a liner, playing as the ship’s band to cover the fare, then possibly work at The Tiles as a resident band. They embarked in April 1967 on the liner Ellinis.

Sounds Unlimited aboard the luxury cruise liner Ellinis, bound for London. The new band was (rear) Ben Kaika on bass, Paddy Beach, (front) Johnny McCormick, Alan Galbraith, Reno Tehei.

Sounds Unlimited had to learn quickly when the beat band arrived in a still very Swinging London; it was a town where Pink Floyd, Hendrix and Sgt. Pepper held sway. “When you are a young band coming from New Zealand where you’re used to playing everything from Small Faces and Manfred Mann covers to suddenly having to get on a stage where you’re going to be followed with THE WHO, it’s a bit spooky. It’s very spooky. So, on the trip home we started to turn all of our cover versions into things that sounded partly original.”

The band only stayed a few weeks in the UK before returning to Wellington in July, once again as a shipboard band. After a short national tour they went their separate ways. Back in Wellington and without a band, HMV suggested to Galbraith that he launch himself as a solo act. Artist manager Dianne Cadwallader, however, was unenthusiastic about having another solo act to complete with her primary talent, the teen-pop sensation that was Mr Lee Grant, and so she suggested a duo with Auckland-based Ken Murphy. The pair agreed and Galbraith moved to Auckland, where – now signed as solo artists to HMV – they were launched as The Real Thing with a single, a cover of The Ronettes’ ‘Walking In The Rain’ in early 1968. Cadwallader toured the duo as support to Mr Lee Grant. However ill health, this time a kidney infection, again waylaid plans and The Real Thing split after one single when Galbraith was hospitalised for three months.

The Real Thing: Alan Galbraith and Ken Murphy

The producer

In hospital Galbraith had plenty of time to ponder his future and decided that it was as a record producer – his label, HMV was the obvious place. He wanted to make records, not just his own, but for the not insubstantial roster of the local company. His first chance came in 1969 when HMV producer Howard Gable moved to Australia with his new wife, Allison Durbin. However, Peter Dawkins, just back from London, was offered the job by HMV and Alan was left wondering what was next.

The immediate answer came when he was offered a partnership in a new record company, Independent Record Productions, soon to be renamed Direction Records; his partner was a former HMV employee Kerry Thomas. Galbraith quickly recorded a single for it, the Sonny Bono-penned ‘Where Do You Go’, backed with Ashford and Simpson’s ‘Rose Growing In The Ruins’. Both were produced by Bob Gillett at Mascot Studios in Auckland.

Alan Galbraith performing at Wellington's The Place, circa 1966. - Ken Cooper collection

HMV, who still had Galbraith signed as a solo act, declined to issue it and only the B-side would ever see a release, on the flip of a Peter Dawkins-produced track, called ‘Serving A Sentence Of Life’. Galbraith then decided to sell his shares in IRP (Direction Records). “[The single] is best forgotten I think. Before we got to do any more, I went back to Wellington. I really wanted a staff producer role at HMV. Kerry suggested I might want to transfer my shares to Guy [Morris] as they wanted to get into retailing. I was only too happy to do that, as I was not interested in selling other people’s records.”

A final Alan Galbraith related release for Independent Record Productions was by The Wedge, a Wellington soul band: their cover of Leonard Cohen’s ‘So Long Marianne’ was recorded in the HMV studios. It was the very first record to feature the credit ‘Produced By Alan Galbraith’ when it was issued by HMV in September 1969.

The first credit "Produced by Alan Galbraith" to appear on a record, in 1969 from Wellington soul band, The Wedge.

When Galbraith was hired by HMV it was still not as a staff producer; instead initially he stacked records in the warehouse, continued to play in clubs on the weekends, and took the lead role in New Zealand’s first rock opera, Jenifer, written by Clive Cockburn and Val Murphy. However, he always kept an eye on the desired studio job.

“I soon spent every available moment working in the studio as a musician, singer, composer – whatever was required, with or without pay. I would have scrubbed the floors if that’s what it took. I soon got to see how it was all done.”

Alan Galbraith in HMV's studio on his first day as a full-time producer in 1970

His chance came in early 1970 when HMV and Peter Dawkins decided they needed a second producer and the eager young musician was offered a job at HMV. He would be working for New Zealand’s biggest record company as an A&R man, and in the studio as a producer. At HMV’s Wakefield Street offices in Wellington, he would share an office with Dawkins.

Peter Dawkins in the control room at HMV studio in Wellington.

“I didn’t report to Peter as such, we tended to work quite separately, but he was then very successful, so I tended to get a lot of the more basic work to do such as choirs, instrumental albums with people like Garth Young, Allan Gardiner, Jack Thompson and various cultural groups and orchestras.”

Jack Thompson’s final LP for HMV was recorded live at the Russley Hotel in Christchurch in 1971. With Ralph Walker on bass and Lance Glanville on drums, the album was produced by Alan Galbraith.

Ironically the first release as an HMV producer for the man who would go on to be the company’s top producer in the mid-1970s was a Christian brass band 45 by The Young Salvationists, signed by the company’s boss Alfred Wyness and issued in June 1970. It was not an atypical situation though and it was soon followed by lounge singer Paul Fisher’s ‘Lady’, the classic wistful pop of The Kal-Q-Lated Risk’s ‘I'll Be Home (In A Day Or So)’, and Brendan Dugan’s ‘Little Miracle’. As Alan recalls, “I did everything. I’d be in the studio with Highway at night. The next day I'll be recording David Curtis, a 13-year-old boy soprano. And the next weekend I'll be down in Christchurch recording the Salvation Army band and then next week I'll be recording Ngāti Pōneke Māori Club.”

Later in 1970 it was Brendan Dugan who gave Galbraith his first pop album credit with his A Touch of Nashville long-player. In the interim, as an artist, Alan Galbraith issued a further solo single: ‘The Old Man’, produced by Peter Dawkins. For this he won the NZBC’s Studio One songwriting competition (it was also recorded by Eddie Low).

Brendan Dugan's A Touch Of Nashville, released in 1971 and produced by Alan Galbraith.

In mid-1970 David Curtis – a 13-year-old Wellington schoolboy with a crystal-clear, unbroken voice – was signed to HMV by the company’s singles head, Bruce Ward, who took him to Galbraith, saying “you have to record this guy”. The resulting debut single was a somewhat sugary cover of the 1950s standard ‘Wheel Of Fortune’ recorded with the New Zealand Symphony Orchestra. Initially nervous about the result, the song proved to be a massive hit when released in July, selling some 17,000 copies, and was a finalist in the end of year 1970 Loxene Golden Disc.

Curtis’s follow up, the self-penned ‘Take Your Leave’, was a finalist in the Yamaha World Music Contest in Tokyo, to which Alan and David travelled in late 1971. At this time, Galbraith was also appearing in TV shows as a solo entertainer, working at the Majestic Cabaret in Wellington, and continuing to do commercial sessions. He sang the groundbreaking TV ad for Gregg’s coffee, ‘Different Places’.

From the mid-1950s until the end of the 1970s, His Master’s Voice (NZ) operated on several levels (from June 1972 it was called EMI [NZ] Limited). The company was a wholesaler and a retailer of a vast range of international music, from not only its own labels Parlophone, Columbia, Capitol and HMV, but also from licensed labels such as its global competitor Decca, Tamla Motown, the various labels combined under the Stateside brand and much more. They also manufactured and retailed domestic and electronic goods via a network of stores. Galbraith: “The guys heading HMV Records were not music men, they were sales men who sold records alongside whiteware and brown goods [stereos].”

Composer Alan Galbraith and arranger Brian Hands with the tape of 'The Old Man' after the song had won the NZBC’s Studio One songwriting competition in 1970.

On the other hand, HMV was also very proactive from the mid-1950s in signing New Zealand artists to the company; this was supported by the substantial revenues from the international sales, although the local artist roster was expected to show an overall profit. That meant that big-selling local acts could support an adventurous A&R policy and so it was, especially as the 1960s turned into the 1970s and Peter Dawkins and Alan Galbraith were largely given free reign as to who they wanted to sign and record. Artists were not charged for studio time – although their royalty rates were low, around 5% to 7% – but this policy allowed these adventurous producers to sign and record acts that may otherwise not have been recorded in a more strictly profit-driven environment.

In 1971 Galbraith signed left-of-commercial-centre Wellington band Highway to HMV. Known for their epic and hypnotic live sets, it was a brave local signing and offered challenges, not least how to turn their extended songs into album length tracks. It caused a clash between the producer and the band, who didn’t want “the man” interfering with their art.

Alan Galbraith in the studio with Highway, 1971.

Galbraith recalls, “They didn’t really trust me … I never interfered with the material at all – I went to all the rehearsals. I just tried to get a decent sound. I tried to figure out how to get the best out of the band, knowing the shortcomings of the engineers at EMI who wouldn’t want to work past teatime and all that stuff going on. I needed to work out how I could get something out of these guys that would work. I didn’t want to interfere with their music and I wouldn’t profess to tell them how to play that, but I did try and get the things sounding as true to what the band sounded like as I possibly could. I went to lots of gigs and lots of rehearsals, went in the studio and said let’s mic it this way. Let’s set it up and let’s just play it like it’s live and it kind of worked. But they could be difficult buggers, you know, just difficult … it was like I was the establishment and EMI was the enemy.

“Later on we all became great friends … but at the time, I think because I was doing David Curtis during the day and Highway during the night they probably thought, ‘what are we doing with this guy?’ The album says ‘thanks to Alan who tried’.”

His trying seems to have had a positive result: in 2009, Nick Bollinger included Highway’s record in his book 100 Essential New Zealand Albums.

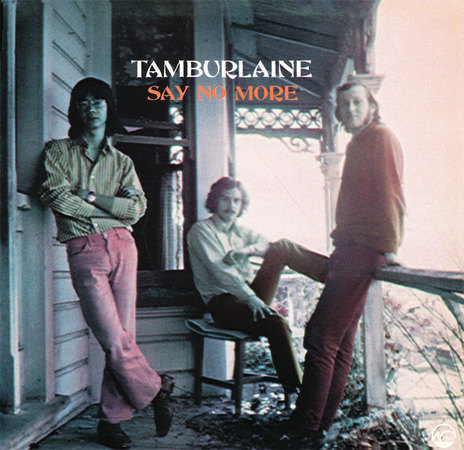

Galbraith also produced the debut album by progressive folk rock band Tamburlaine at EMI, for the indie Tartar label.

Say No More, Tamburlaine's 1972 debut album on Tartar Records, produced by Alan Galbraith and named by Nick Bollinger as one of the 100 essential New Zealand albums.

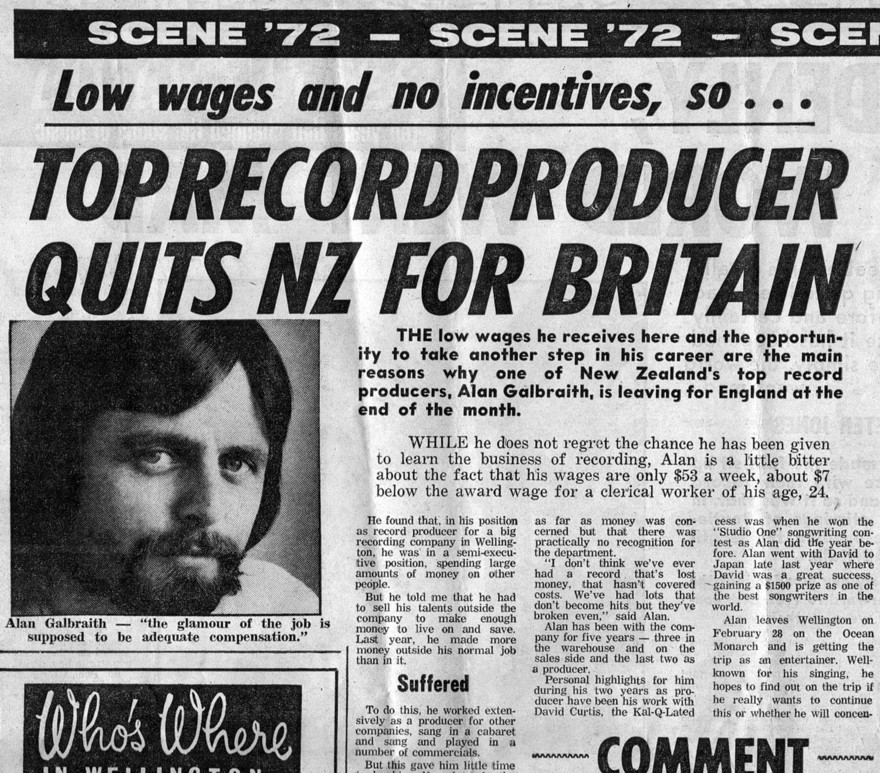

For all the freedom, however, neither Peter Dawkins nor Alan Galbraith were completely happy with the often very conservative corporate climate at EMI and both decided to leave the company in 1972. “I left HMV under a bit of a cloud. Peter and I had been quite critical of the way we were treated and how little we were paid, and both decided to go elsewhere.

Burning bridges! The interview with Alan Galbraith about HMV, 1972.

“We were interviewed for the Sports Post newspaper where I didn’t hold back. Peter, to his credit, was a little more circumspect. He scored a job at EMI Australia and I just walked out and played my way back to the UK with the P&O line. Once I got there I did the rounds, finally getting to EMI who told me they had a letter from HMV New Zealand management with copies of the offending press clippings telling them not to hire me. EMI UK’s response was to ask when I could start.”

--