Ragnarok with Lea Maalfrid (L-R): Ramon York, Mark Jayet, Lea, Andre Jayet, Ross Muir.

Those with a religious disposition might be inclined to declare it a miracle. Even a confirmed agnostic would have to admit that it’s an unprecedented and amazing phenomenon. The idea that a 47-year-old album by an obscure progressive rock band could rocket up the New Zealand charts in 2022 to sit pretty at the No.10 position … it feels surreal.

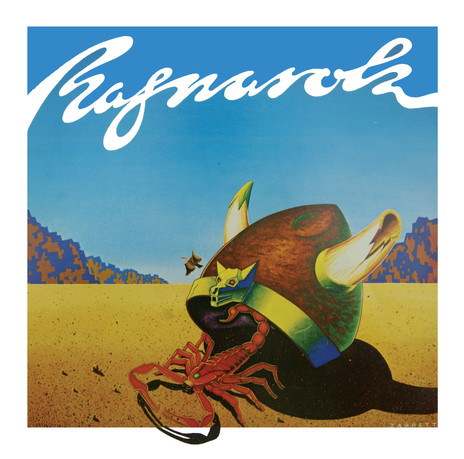

This unlikely event occurred in March 2022 with the Frenzy label reissue of Ragnarok’s self-titled 1975 debut, which meant that it briefly broke the stranglehold the likes of Six60 and L.A.B. have on the Top 20, bringing a flash of fresh (albeit very old) Nordic-inspired oxygen to the weekly popularity parade.

The 1975 debut album from Ragnarok, reissued on Frenzy in March 2022.

The chart action was a blip, for sure, but the genuine interest in the band’s until-now impossibly rare records is gratifying to the surviving members, especially given the short shrift the group got at the time. It wasn’t that Ragnarok were unpopular, just that like so many other New Zealand acts of the era, a combination of managerial issues, poor timing and sheer bad luck saw their potential evaporate.

In fact, from the group’s inception they were a phenomenally popular live act. Drummer Mark Jayet explains that within a few weeks of their first Auckland performance in early 1974 they were packing out venues and punters were queuing down the street to see them – much to the chagrin of more established acts like Dragon, who they were soon to displace at an inner-city residency.

A mere 16 years old at the time, Christchurch born-and-bred Mark Jayet remembers getting the call from his older brother, Andre, to join his group Sweet Feet in Auckland. Andre had been playing in a band with Sharon O’Neill, and when she left to do her thing, he already had the nucleus of the forthcoming group with Ross Muir (bass guitar) and Ramon York (guitar, vocals). Ramon had introduced Andre to singer-songwriter Lea Maalfrid and her then-husband, Tony Wyber, who became the group’s manager.

Lea Maalfrid, after her stint with Ragnarok. - Photo by David Roberts

“They sent me a tape of some of the stuff they’d been working on,” says Mark, “and the sound was really good, so I was like ‘wow, I want a piece of that’.”

“I remember driving all the way up there in my old blue Vauxhall PA, a six-cylinder that used to go like the clappers but had bits of metal on the side doors that kept on falling off. When I came into Auckland, I’d never seen a motorway, nothing like that. It was absolutely pouring and I couldn’t see the lanes and I was like ‘holy crap!’”

Mark hardly had time to put his feet down on the Auckland isthmus before he was whisked off to Gisborne, where the group had a three-week stint at the Sandown Park Hotel. And, as unlikely as it seems, this is where Ragnarok was born.

“During the day we rehearsed and got new ideas together. We changed our name and came back to Auckland as Ragnarok. The funny thing was that within three weeks we had queues down the street at Mon Desir (hotel). For me it was mindboggling. “Me, Ross and Andre were living in a cabin in the Takapuna Tourist Courts. It was dirt cheap and you’re on the beach front at Takapuna. And the Mon Desir was just across the road and we had all our gear in there so we could just go in and potter round during the day.”

Concert poster for Ragnarok by an unknown artist, 1977. Earthborn and Earlybird were Palmerston North bands that performed original material. By Attribution Alone, Palmerston North City Library

The idea of the name change to Ragnarok and the new Nordic theme of the original material they were working on came from Tony Wyber, with some input from Ramon York, according to Lea Maalfrid who, despite looking the part, is not of Scandinavian heritage. Having grown up in Central Otago and spent her teenage years in Dunedin, by 1974 she was already an aspiring singer-songwriter when she turned her attention to writing material specifically for her new band.

“Tony is the one that put me together with them, and he’s the one whose idea it was for Ragnarok,” says Lea. “He was interested in Nordic mythology. And so, songs like ‘Fenris’ – those songs were written to go with that kind of theme. It was all his idea, and he was a very talented person, actually.”

Ragnarok thanks all their "cosmic" friends in Christchurch, 1975.

But the times weren’t conducive to original material. Audiences typically saw local bands in pubs, where – if they were lucky – they held down residencies and were expected to play a big chunk of covers with only a titillating dash of their own stuff. This is the context of the time that audiences in 2022 might find difficult to comprehend. Accordingly, it’s probable that the group’s live reputation relied more on their ability to put on a cracking show with great sound, tight musicianship, and some outrageously glam costumes. Not to forget the dry ice.

They called their own material space-rock or cosmic rock.

“At the Mon Desir when we first started, we’d do two or three sets a night, and for the last set we’d all go and get dressed up,” says Mark. “I would wear blue-satin hot pants and red tights and Andre would do the same.”

Mark says that they called their own material space-rock or cosmic rock – “bring your LSD along and have a trip!” – but during one of their sets they also entertained with renditions of Suzy Quatro’s ‘Can The Can’, David Bowie’s ‘All The Young Dudes’, The Moody Blues’ ‘Nights In White Satin’, Sweet’s ‘Ballroom Blitz’ and Led Zeppelin’s ‘Immigrant Song’.

Lea says they also performed Zep’s ‘Whole Lotta Love’, Bowie’s ‘Gene Genie’ and even Ike and Tina Turner’s ‘Nutbush City Limits’.

Mark: “The light show at the Mon Desir was pretty amazing for its day and we’d have dry ice and we’d come out playing this trippy music and start off with two snares (Andre and Mark) and hoon into ‘Ballroom Blitz’, and then we’d do a few more songs and Lea would come out. One of the songs that went down well was ‘Fire In The Sky’ because it was pretty intense. And that’s how it started. Nobody in Auckland was doing anything like that. We didn’t consider it glam rock, it was just a show, and it took off.”

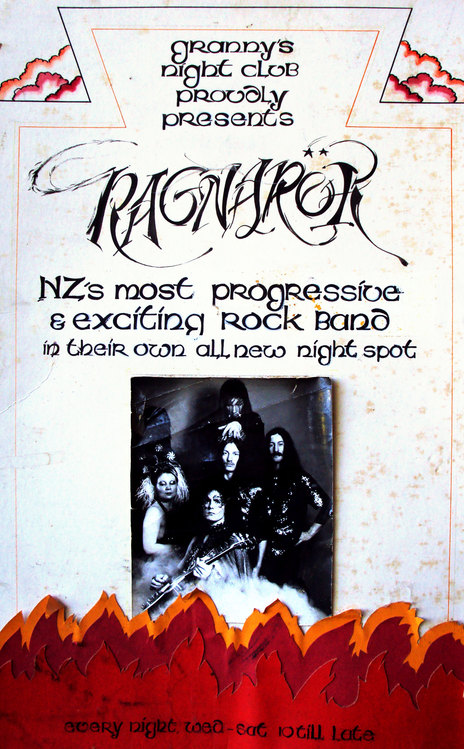

Soon the group’s reputation would score them a residency at Tommy Adderley’s Durham Lane nightclub Granny’s, where the same phenomenon occurred.

The poster for Granny's in Auckland's Durham Lane West. Ragnarok became a resident act at the club in the mid-70s, playing four nights a week. - Grant Gillanders collection

“I remember a lot of the local musos were pissed off with us,” says Mark. “‘Who are these young upstarts coming from the South Island and taking over the place?’ Dragon hated our guts. Probably justified because they were the resident band at Granny’s and they got booted out. They did the place up and put us in there and called it Ragnarok’s nightclub and there were queues all the way down the lane. Upstairs was Granpa’s where the more aficionado-type Auckland musos went – the ones that were playing the funk and were technically good, whereas we were just up there playing ‘Ballroom Blitz’ and shit like that.”

“I don’t know what we were on but we practised solid for 18 hours.”

– Mark Jayet

The residency at Granny’s gave them the opportunity to rehearse original material during the day. “We had to take the people with us so we played all the covers, but while we were in there during the day, we’d be rehearsing the original stuff. I remember once at Granny’s – I don’t know what we were on but we practised solid for 18 hours. And the only reason we stopped I think, because we were so into it, was because we were just about falling over.

“There were times where there might be a four or five-bar section of a song and we’d work on it for a day. Then you strip it back, dress it back again. Because we had a TEAC 4-track recorder so we could record it and play it back and ‘no, that’s not right, that’s not right, try again’, and we’d analyse it.”

Some of the material was worked up from scratch by the four guys while Lea also contributed several of their best songs. “She would give us a basic song and sometimes she wasn’t amused with what we’d done to it,” says Mark. She’d say, ‘I have to relearn this whole bloody song now!’ because we’d put some weird time signatures in it.

Backstage with Andre Jayet and Mark Jayet, Ragnarok. - Grant Gillanders collection

“The thing was that when we were doing these 18-hour rehearsals Lee was never there. So, once we had the song basically finished, or our version of it, she’d come in and sing it and we’d try to put it all together, because there was no point in her coming in and twiddling her thumbs while we played the same five bars for an hour and a half. She’d come in and we’d have a proper rehearsal with all the songs and once again it would take a long time to get them to where we felt they were completed.”

Mark clearly has fond memories of those early days when Ragnarok were holding court in Auckland. “[At that age] you don’t have too many other responsibilities and you live for it. It was just your life, it took over your life, and we used to swan down the street with all our gears on, part of the scene of Auckland and all that. And when you put so much time and effort into it and you’ve got musos who’ve got reasonable talent you will come up with something. But at the same time, we were pretty much, the four of us, on the same wavelength of what we wanted to achieve. Lea wrote a lot of the songs and when we performed live, she enjoyed doing her own stuff. I remember afterwards stumbling down to the White Lady for a feed.”

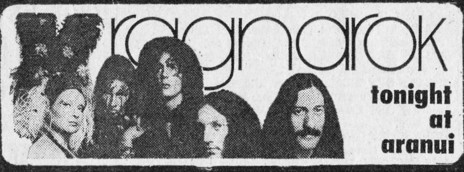

Ragnarok at the Aranui Tavern, Christchurch.

Playing the traps was what it was all about for any band that aspired to professional status, and Ragnarok – when it wasn’t in a residency – toured relentlessly. For the two years Lea was in the band they managed two national tours and Mark says that during this time, the group lived on the road. “We never had a flat where we lived, just kept travelling, going up and down and up and down.”

Lea has no memory of singing on the album at all.

While the boys in the band were young and free, it was different for Lea, whose first love was classical music and whose own songs veered towards balladry. “And by the way, before my career started in any way shape or form, I had two children,” she says. This responsibility changed the way she experienced her time with the group. “None of it was easy, at all. People can rock up and think it’s all sex drugs and rock and roll. Not for me. I was thinking ‘better go home now and…’ It was more like a job for me.”

No wonder that the album doesn’t figure prominently in the group’s collective memory, and that Lea has no memory of singing on the album at all – despite her wonderfully elastic voice giving the songs a real boost.

The band had signed to the fledgling Pye-distributed Revolution Records, a short-lived label run by Mexican/Canadian accountant and would-be entrepreneur Antonio Santamaria Fernandez, whose other main act was the Māori Volcanics in its Billy T. James era.

The 1975 Ragnarok single 'Fenris'.

Recorded in early 1975 at Stebbing Recording Studios, the project was clearly on a tight budget and the group were expected to perform at their best with no prior experience of the studio environment.

“I was pretty awestruck when I walked in,” says Mark. “I thought holy God, look at this place, all the gear! I remember going in there and they didn’t tell me anything and I didn’t know much, and we just started playing and did one take and I thought ‘we’ll do the proper take now’, and they said, ‘that’s it!’. And I thought ‘oh shit!’. A lot of them were first or second takes and then that was it, you moved on.” The whole album took just over a week to record.

“Initially when it first got released, we were all annoyed that it had the shit compressed out of it and it was slightly slower or faster … you’d play it and it would be slightly out, the speed was different. Not by much, but we were pretty disappointed by the sound quality of the album. And not only that but you hear all the mistakes that you’ve made.”

Lea may not remember the process, but she can recall her two main contributions to the album, which she sang live many times. “The song ‘Fenris’ is specifically Nordic,” she says. “But ‘Fire In The Sky’ isn’t. I’d hesitate to write such a song now because I find the lyrics quite alarming. It’s quite a hard song to sing and I’m pretty self-critical. I was only pleased with how I sang it once, and I sang it many times. I was thinking quite recently it would have been a wonderful song for Freddy Mercury to sing, because it’s quite operatic.”

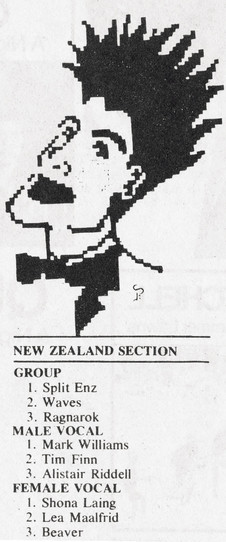

Hot Licks readers' poll of 1976 sees Ragnarok and Lea Maalfrid placed in the top three.

The album barely caused a ripple at the time, despite a full-page ad in Hot Licks magazine and a smattering of posters around town. Maybe the group’s audience was looking for the same experience they got from the live show, or perhaps they expected similar production standards to overseas contemporaries like Pink Floyd, with that group’s massive budgets, celebrity recording engineers and as much time as they needed in the studio to sculpt the perfect product.

But taken on its own terms, Ragnarok is special, and time has been kind to this unique fusion of psychedelia, progressive and cosmic rock. And happily, the reissued vinyl and CD sound way better than the original pressing, thanks to a careful remastering by Steve McGough and Robert Stebbing.

Just prior to its release in August 1975, however, Lea left the band. “It was very difficult for me to tour with two children,” she says. “And also, I felt myself going off in a different direction, musically speaking. I could see that they could go very well without me.” She is, however, fond of her former colleagues in Ragnarok, with special mention of the shy but photogenic guitarist/singer Ramon York. In the liner notes of the reissued debut album, Maalfrid said, “Having to take my four-year-old daughter with me when we toured started to get me down. Another deciding factor happened one night when we were in Timaru when a tornado ripped through the motel where we were staying. Someone knocked on our door and told us to leave the room immediately. I grabbed my daughter and as soon as we got out of the room a huge piece of corrugated iron came through the large window and landed on the bed. We had a lucky escape.”

Lea had also split from her husband, Tony, and so had the band. “He had great ideas,” says Mark, “but we wanted to get into Australia, and he went over there and spent a whole lot of money that we didn’t have – caught taxis here and there and bought handbags and things – and we were living on about $30 a week.”

Instead of an Australian excursion, the group invested all their money into a huge PA stack built by the legendary Peter Perreaux, with which they continued to tour over the next few years.

By now, those lucrative Auckland residencies had dried up and the group was working out of Napier (also the home of Perreaux). The group had become precision-tooled through the rigours of the road and even today, boomers up and down the country reminisce fondly about their live encounters with Ragnarok in those later years.

Of the legendary Perreaux PA system, Mark says: “We just knew that we needed something like that to give the music a bit of justice. That’s what we were trying to do. There was no one else with a PA like that back in the day. Nine-and-a-half stone weaklings lugging this shit up the stairs of the bloody Lion Tavern in Wellington!”

Ragnarok live, 1976.

Of equal importance in the Ragnarok mythos is the group’s Mellotron – one of only a few in the country back then – with which Andre Jayet gave the group a big part of its signature sound. “Every time you shifted it, you’d have to retune it and Andre would spend hours with this thing in bits getting it ready for the night’s performance. It was all tapes, but it was an amazing sounding instrument. Each note would only last for eight seconds, and you’d take your finger off and the tape would wind back! Crazy!”

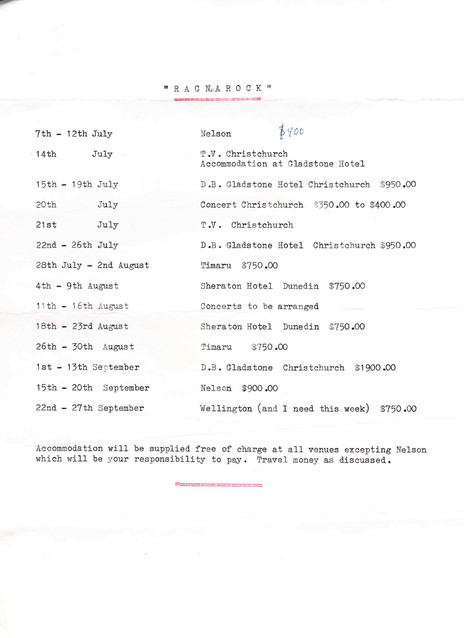

Ragnarok's South Island tour itinerary, 1975. No accommodation provided in Nelson.

But regrets, they have a few. “We never managed to get to Aussie,” says Mark. “We should have just gone but for whatever reason it just didn’t pan out, so we just kept travelling.

“We spent all this money on the Perreaux PA thinking that we would be able to claim it on tax, but we found out that we could only claim 10 percent depreciation. So, we ended up with a massive tax bill and they wouldn’t let us out until it was paid. And by the time we paid it we’d run ourselves into the ground.

“Everything was going back into getting the show up and running. We had a big Bedford truck to lug it all and we owned it all, but the money we got was just piled back into buying more gear. With the constant touring and having to pay off the bill … we were just so tired by the end.”

Ragnarok - Nooks (Polydor, 1976)

After Revolution Records called it a day, in 1976 they had recorded a second excellent album sans Lea: Nooks, for Polydor at EMI Studios in Wellington. But times were changing. With the back-to-basics grittiness of punk about to seep back to Aotearoa the expansive soundscape, long hair and Norse mythology of the group soon seemed gauche. Split Enz were uniquely placed to adapt with the times but groups like Ragnarok found themselves out of place and out of time.

They pulled the plug in 1978. “There was all the punk and what we were doing was sort of…” he trails off. “In the end we knocked it on the head because we were just worn out, really.”

Andre Jayet had been quietly working towards seeing a reissue of Ragnarok when he died in May 2020. To his credit, music historian/archivist Grant Gillanders took on the project and saw it through to its completion. When Mark received the finished pressing, he took it to the cemetery to show Andre and his parents.

What are they doing now? Lea Maalfrid has had a successful international songwriting career and is about to release new material, Ramon is a Christchurch-based luthier, Ross still performs in Alice Springs, and Mark lives in Christchurch where he performs with several bands.