Magazines come and go, but few have the impact and lasting legacy of New Zealand’s Hot Licks. The local monthly magazine helped spark the careers of local bands like Split Enz, Dragon and Waves. Jeremy Templer writes about Hot Licks and working with founding editor Roger Jarrett.

–

The Sweet, Alvin Stardust, Emerson, Lake & Palmer, Yes, Leo Sayer, The Bee Gees … if you deleted from living memory much of what passed for popular music in the early 1970s, you’d be doing everyone a favour.

Yes, most of what we listened to back then deserves to be forgotten. But not all of it. There were bright spots, even in what were bad times for good music.

In Auckland, 1974, we had Radio Hauraki’s Buck-a-Head concerts, for instance. And there were record stores catering for less mainstream tastes like Direction Records and, appropriately enough, Taste Records.

Add to that, there was a new music magazine. First published in February 1974, it’s hard to overstate the importance to New Zealand music of the free monthly magazine Hot Licks.

Waves, signed to Direction Records, had strong support from Hot Licks with a cover in September 1975

Over the course of 27 issues and a two-and-a-half year existence, the magazine jump-started the careers of local bands like Split Enz, Dragon and Waves. It helped pave the way for visits by international acts like Roxy Music, Little Feat, Bob Marley and others. And Hot Licks blazed the trail that another magazine, RipItUp, would soon follow.

Early issues of Hot Licks replicated the original format of Rolling Stone: a folded tabloid, unstapled, printed on newsprint, with economic but effective use of spot colour.

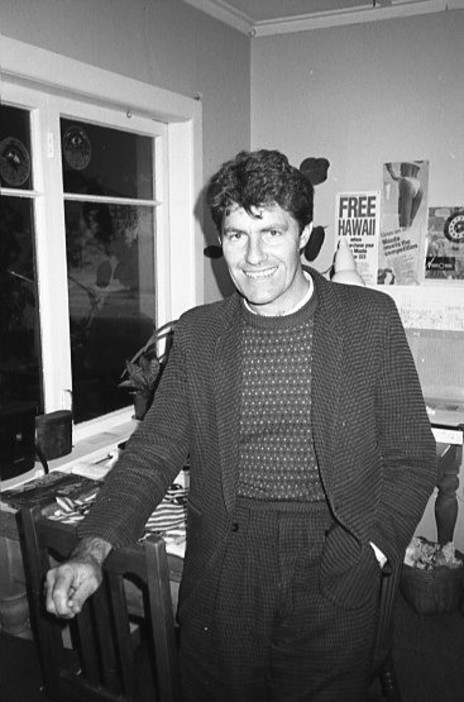

Roger Jarrett

The name? It came from San Francisco’s Dan Hicks and his Hot Licks. Founding editor Roger Jarrett had a soft spot for the band.

Jarrett’s editorial in the first issue announced the magazine’s purpose: “Hot Licks is published to fill a gap. To provide for those people who consider themselves reasonably aware a vehicle through which they can express themselves and state their point of view …” And, he went on, “… it is envisaged that Hot Licks (like several overseas publications) will contain both cultural and political articles under the guise of a music magazine …”

Jarrett wasn’t a journalist: he was a graphic designer and illustrator. He’d been working in advertising before Direction Records’ Kerry Thomas and Radio Hauraki’s David Gapes enlisted him as editor for their new music magazine. Rhys Walker, who then ran the Direction Records store in Swanson Street, recalls: “Roger had always said that there was some great music happening in New Zealand, but you couldn’t read about it here.” Hot Licks would change that.

Roger Jarrett by Peter Adams, July 1975

The first few issues were largely all Jarrett’s own work, with a little help from some friends. They included illustrator Dick Frizzell. Years later, Frizzell recalled those times:

“Roger down in the Hot Licks offices – seeing him all unshaven and red-eyed after staying for a week pasting up that ground-breaking music mag. Printers screaming for money, and Roger’s still raving, writing a fiercely loyal deadline piece on Split Enz with one hand and an intro to this strange new music – reggae – with the other … this is the guy who taught me the meaning of boundless enthusiasm!”

That enthusiasm was evident in everything Jarrett wrote. Disappointed by poor attendance at local gigs, he rallied for readers to wake up, get over their indifference and start supporting local artists. Or, he warned, they would be lost to Australia – a move most musicians then considered necessary for any chance of recognition and success.

Jarrett wanted Hot Licks to be a magazine that gave everyone a voice. But its success was overwhelmingly due to his drive and vision.

Direction Records both owned and used Hot Licks as a marketing tool, speaking directly to their target audience

Parent company Direction Records made free copies of the magazine available in all its stores. Like the record stores, the magazine would initially only be available in Auckland, and was intended (as Jarrett declared in the first issue) for young Aucklanders.

Hot Licks covered the local and international music scene, and interviewed visiting acts. Film, theatre, books and TV programmes were regularly reviewed. And there were occasional articles and commentary on global and local politics (such as East Timor and the Fretilin; Rhodesia; NZ elections) and social issues (abortion and nuclear power).

Editing, design, layout and production would long remain solely Jarrett’s responsibility, but unsolicited contributions were encouraged. Before too long the magazine had attracted a lengthy cast of writers, illustrators and photographers. Some were already locally known, others soon would be.

Regular writers, and there were many, included Tim Blanks, Gordon Campbell, Roy Colbert, Terence Hogan, Wellington T. Choy, Graham Donlon and Brian Thorogood. Illustrations became a feature of the magazine, provided by Frizzell and others like Peter Adams, Barry Linton and Frank Womble. Roy Emerson was the magazine’s on-call photographer.

Musicians also became contributors. Henry Jackson, then of Cherry Pie, was perhaps the most prolific, but others included Mike Chunn (then of Split Enz) and Waves’ Graeme Gash.

Pseudonyms were popular amongst the Direction team, allowing them to say in print what they might not have wanted to as Direction staff. Tubes Paradise was Rhys Walker; Clark and Lois was Grace Sloan (now Grace Cardwell Scouller) while Sol Amio was none other than Jarrett himself.

As Direction Records opened stores in Hamilton, Tauranga, Wellington and Lower Hutt, Hot Licks’ readership grew. Eventually, its 10,000 copy print run would prove insufficient. And, ultimately, it wasn’t a magazine that Aucklanders could keep just for themselves.

Reggae Got Soul

Back then, Jarrett liked everyone from Little Feat and Emmylou Harris to Asleep at the Wheel, Allen Toussaint, Ry Cooder, The Meters, Bob Marley, Toots and the Maytals, Split Enz, Waves, Skyhooks and The Tubes.

“Dad had incredibly eclectic tastes – partly why he helped set up the magazine,” his son Ben would later write, “I was exposed to a very diverse range of musicians: the Congos/ King Sunny Ade/ Roxy Music/ Neu/ Eric Satie might constitute a musical transition in the Lancia as we went on a road trip. It rubbed off, and I like almost every genre, given the right artist …”

Other writers were discriminate in the genres and artists they liked. There were champions for Can and Kraftwerk; Roky Ericksen and Captain Beefheart; The Flamin’ Groovies and Dr. Feelgood; Miles Davis, Dr. Tree and Gary Burton; Lou Reed, Ragnarok, Space Waltz and The New York Dolls. All were given a voice. Where most music magazines of the day were secular in their coverage, Hot Licks aimed for diversity.

The magazine did not skirt controversy and didn’t shy from having a contrary point of view. And, true to its intent of providing a forum for different points of view, the magazine’s reviewers themselves were sometimes at odds with each other.

Tim Blanks (later to become a well-known international fashion critic) would praise Bowie’s Station to Station but found Lou Reed’s Coney Island Baby tiresome. On the other hand, reviewer Richard Best thought Reed’s far the better record. Hot Licks published both reviews.

And, while the reviewers around the world were pretty much unanimous in praising Springsteen’s Born to Run, Hot Licks reviewer Peter Puma (Peter Jarvey) proved the exception.

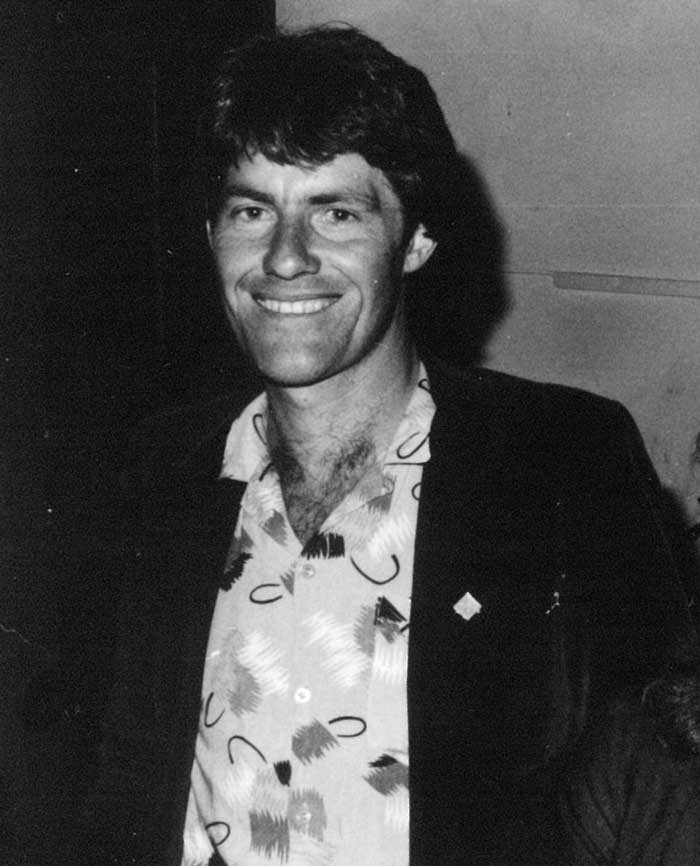

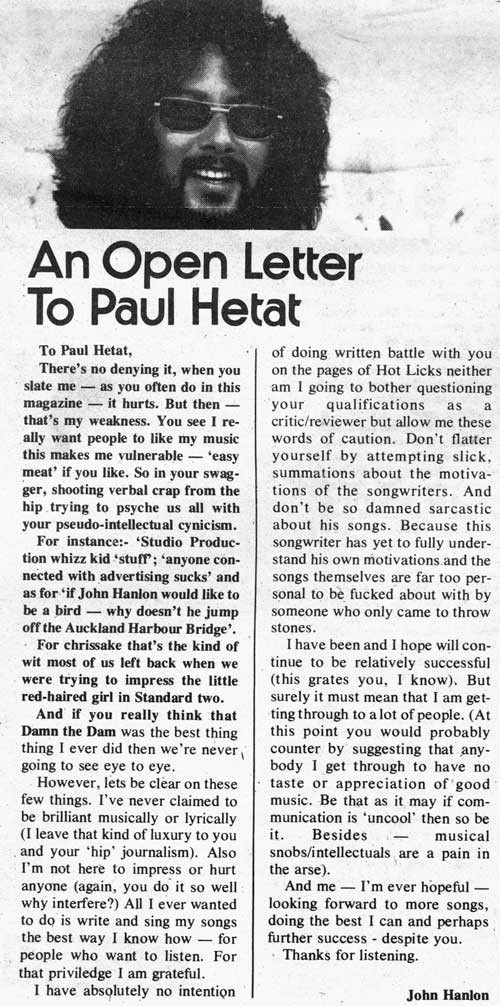

Readers wrote in with a mix of supportive and dissenting views. There were fierce rebuttals from those offended by a review, rebukes for the use of coarse language, and thanks that the magazine existed at all. Bay City Rollers fans were incensed by the magazine’s dismissive comments, Space Waltz fans wanted more articles on Alastair Riddell. And there was a very public spat between reviewer Paul Hetet and local songwriter John Hanlon.

The ongoing public scrap between high profile singer-songwriter John Hanlon and writer Paul Hetet (here spelled as Hetat) was spread over several issues of Hot Licks

As for those with good things to say, a letter from “a NZ music lover” published in the February 1976 issue said what many others were saying:

“Before Hot Licks, the Auckland music scene … was a desert … What (Jarrett) has done (is) to give the whole scene a shot in the arm (his enthusiasm for local music, indeed music in general, is obviously limitless and most inspiring). Hot Licks has pulled together the various pieces and provided us with a national identity, a starting point if you like, from where we (or at least the musicians) can create and foster a music scene equal to any … We are extremely lucky to have something this good …”

Hot Licks gave the local music scene due coverage. But Jagger, Bowie, Roxy Music, Rick Wakeman, Led Zeppelin and Elton John were all on the cover before that honour went to a local band.

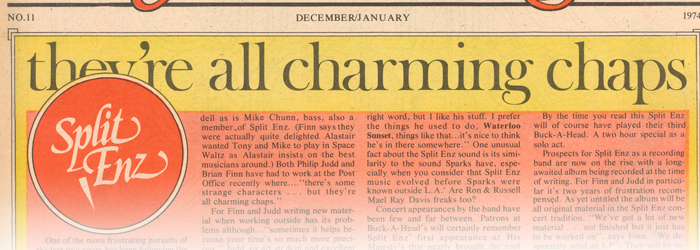

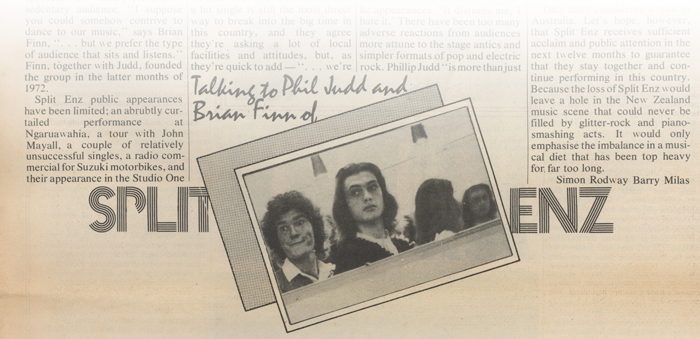

Split Enz made the cover of the August 1975 issue. It was the same month that Mental Notes, the band’s landmark debut, was released. But it wasn’t Jarrett, huge fan though he was of Split Enz, who put them on the cover.

Hot Licks and Roger Jarrett were ardent supporters of Split Enz from their earliest days as Split Ends, with the band appearing in at least 10 issues and a 1975 cover

So Long for Now

The June issue published and with the July 1975 issue ready to start production, Jarrett announced he was off overseas and wouldn’t be back until Christmas.

Published after his departure, his July issue editorial introduced a new editor. But there would be other immediate changes.

With the August 1975 issue, the magazine would be available in bookstores and news agencies (through distributor Gordon & Gotch). And, to support the additional costs involved, it would no longer be free.

Jarrett would later say that putting a price on the magazine had been a mistake. But from August Hot Licks was 40c a copy on newstands and in record stores. Annual subscribers would pay 30c an issue.

There were good reasons for the magazine to be distributed nationally. For one, readers in other parts of the country were more responsive. Letters to the editor (many appreciative, others not so) arrived from Palmerston North, Wanganui, Taumaranui, Napier, Christchurch and Dunedin, even before the magazine was available in any of those places. Comparatively few letters carried an Auckland postmark.

Published while Jarrett was in the UK, the August issue was edited by Roger Thornton Brown. Brown had been working at EMI and was a recent journalism graduate. He was joined by Peter Adams who took charge of design and layout. Adams had done graphics for Radio Hauraki but was yet to be adopted by Hello Sailor. And it was Adams who renamed Brown as Roger Roxx.

Radio Hauraki was a strong supporter of Hot Licks, with ads in every issue

“I wanted a bit more irreverence,” Brown has written in a personal memoir. He wanted “to shake up things, remaking Hot Licks in the mould of CREEM (the US rock magazine), championing bands like The Velvet Underground, Iggy and the Stooges …”

Brown and Adams produced two issues between them, including the issue with Split Enz on the cover. Putting Enz on the cover was a gutsy move at the time.

Yes, the magazine had already been lavish in its praise for Split Enz, but this was to be the first national issue. And, outside Auckland, Split Enz was more likely to raise eyebrows than have people clapping. As for what readers made of the accompanying article, that would be anyone’s guess. The Split Enz story was told in rhyming couplets by Mark Hough (aka Buster Stiggs, later of Suburban Reptiles and The Swingers), under the pseudonym Con Jectcha.

Jarrett returned suddenly in September and wasn’t happy with what the two had done to his magazine. Brown recalls: “Pete and I were called to the publisher’s office and had an awkward conversation about how ‘things hadn’t worked out’ and [were] given a month’s pay in lieu of notice.”

That meant Jarrett was back to doing everything himself, except selling the advertising. That was done by Direction founder Kerry Thomas, who soon found he needed someone else to do the job. For several issues, that person was Grace Sloan, recently returned from Christchurch.

Roger Jarrett in Durham Lane West

In the February issue, Jarrett announced the next issue wouldn’t be out until April. But it would be worth the wait.

“Hot Licks is to take on a new face: a change of size, a new format, a new emphasis and a distinctly new appearance,” he wrote. For those wanting more music news and a guide to who was playing where, there’d also be a new fortnightly supplement. Hot Licks Express would be available free from Direction Record shops, Radio Hauraki and selected “Hot Shops” throughout Auckland.

The original Rolling Stone-style folded tabloid would give way to the more common broadsheet format. That was to help the magazine stand out on newsstands. For cost reasons, however, Hot Licks would continue to use spot colour over four-colour process. And it would still be printed on newsprint.

Jarrett’s editorial also mentioned he needed more staff to allow for the extra coverage. As a one-man-band, he wrote, he lacked the time and patience to report on local artists and new groups, and was already working late nights just to produce the current version of the magazine.

While the music played we worked by candlelight

Fast forward to March 1976 and I was working with Jarrett at Hot Licks, as the new co-editor. Luck played a part – I’d bumped into Jarrett and Sloan working late one night in Hot Licks’ basement office. They were on deadline, both looking so beat I had to offer my services. But I’d met Jarrett before, when interviewing Bryan Ferry, and we’d kept in touch.

I was 20 years old and recently arrived from Wellington; a journalist and layout artist who loved his music and (a bonus) had his own 35mm camera. Five years older, Jarrett was an inspiration, and he quickly became a friend.

The redesign was already well advanced by the time I arrived to help, but together we put out the next four issues. We worked day and night on the magazine. With two of us we got a lot more done; more articles, more interviews. Jarrett would write and put together the reggae issue he had long wanted to do (the May 1976 issue with Bob Marley on the cover). Meanwhile, I contributed interviews with people including local promoter Barry Coburn, Be Bop Deluxe’s Charlie Tumahai, and folkie Brent Parlane.

There was a beat-up record player underneath the stairs, an amp and some dodgy speakers. Next to it, a pile of vinyl records, many of them Direction releases. We listened to almost everyone, nearly everything.

There was the stuff we liked, and the stuff that we played just because it was there. Neil Young’s Tonight’s The Night was one favourite; Patti Smith’s Horses another. Drop into the office and at any time you could be listening to The Meters, The Heptones, Marley’s Live! album (Jarrett had been there, that night at The Lyceum) or even KISS.

Steely Dan’s The Royal Scam became an office favourite. Jarrett would sing along at the top of his voice to ‘Kid Charlemagne’: “Is there gas in the car? / Yes there’s gas in the car …”

There was gas in the car, all right, but not a full tank. The last issue we worked on together (July 1976, with a Steely Dan cover) was also the last to be published.

The Beginning of the End

Direction Records’ Kerry Thomas used to enjoy recounting the story of how he won New Zealand distribution rights to Neil Bogart’s Casablanca Records. There’d been a record industry conference in Hawaii, and the deal was done after he met secretly with Bogart on the other side of the island. He walked away with the rights to releases by KISS, Parliament, and Donna Summer.

Phonogram would become particularly miffed at having lost KISS, but nor were the other majors (EMI, WEA, RCA and Festival) happy to have competition. Certainly not from a new upstart that also had a half dozen or more retail outlets, a national magazine (two if you included the surf magazine Tracks) and a cosy relationship with Radio Hauraki.

By the end of 1975, Direction also had distribution deals with Capricorn, ECM and CTI. And for a good while they had Virgin Records, until EMI won back the rights.

Hit releases would follow, among them Esther Phillips’ ‘What A Diff’rence A Day Makes’ (a top 30 hit for three months), Donna Summer’s ‘Love To Love You Baby’ (Top 10, April to June 1976), and the KISS LP Destroyer (which reached No.16 that June). But it would be a song about a dog (‘Shannon’ by Henry Gross) that got Direction its first No.1 release in July (it stayed in the Top 10 for four months). This was the same song that later caused American Top 40 countdown DJ Casey Kasem so much grief, an audio outtake of his outburst during a pre-recording session featured to hilarious effect in Negativland’s ‘I Still Haven’t Found What I’m Looking For’.

‘Shannon’ was quick to become a hit. But the one song that, whenever I hear it, takes me back to that time – and what would prove to be the last days of Hot Licks – is Elvin Bishop’s ‘Fooled Around (and Fell in Love)’.

The single was a slow burner that eventually stayed in the Top 10 for three months. Yet another hit for Direction that year, it reached No.3 in the New Zealand Singles Chart.

The winners of the 1975 Hot Licks poll

But the record label’s success would cause problems. Big problems. Like pubs need beer, record stores need to have the latest records. And Direction soon faced difficulties supplying its stores with new releases (unless they were on the company’s own label). Resources were tight after the company’s rapid expansion, but the stores soon found it particularly hard to get new releases from EMI and Phonogram. And while it’s hard to imagine any company getting away with it now, Phonogram then required record stores pre-order and prepay for product, mandating the titles each store must stock.

Without new releases to sell, liquidity soon became an issue. With the stores in trouble, so too was the magazine.

Thomas, his partner Guy Morris, and finance manager Karen Howitt handled the business side of things (for the record stores, the record label and Hot Licks Press). Jarrett and I had no involvement, but the problems were obvious even to us by the time we had published the July issue. And, unfortunately, Thomas and Morris couldn’t agree on what to do: it had been Thomas who had wanted to expand the business, whereas the more laid back Morris would have been happier with just a few stores.

Jarrett, wary of the politics involved and approaching burnout from his efforts, was itching to get back to doing something more creative and fulfilling. He left before we completed the August issue.

He turned to fashion photography and later, in what was another surprise to most everyone who knew him, took a job in promotions at record distributor WEA. He found more time for surfing, eventually moving to Mount Maunganui and writing a movie screenplay about surfer Mickey Dora.

Roger Jarrett and friend at David Bowie concert, Western Springs, 2 December 1978. - Bruce Jarvis Collection, Auckland Libraries Heritage Collections 1704-1844D-33

Fade to Grey

While it was clear things weren’t right at Direction, I wasn’t ready to give up. And, for a while, I still thought the magazine could be saved. I carried on with the August issue by myself.

Ready for publication, the August issue had enough ads to cover costs, but there was a problem. The printers, used to late payments, were aware that things were amiss. And they needed to be paid before they’d print the new issue.

Like a good book you read slowly to savour to the end, I kept going back to Direction’s Albert Street offices each day, hoping for good news. I was planning and preparing for the September issue, even as it appeared increasingly unlikely that the August issue would be published.

Hot Licks may have survived if it had been separate from Direction’s other businesses. But then came the news it was all over: Direction went into receivership, dragging along with it Hot Licks Press, the record label and Tracks magazine. All assets were liquidated: Hugh Lynn bought Tracks but Hot Licks was gone; the last issue never printed.

The Direction Records and Hot Licks magazine Xmas card, 1975, with a rough tribute to Bruce Springsteen's Born To Run album – the hot record that year. It shows Roger Jarrett and Direction owners Guy Morris and Kerry Thomas, with Hot Licks' Grace Cardwell Scouller in the corners. - Photo by Roy Emerson

Eleven years later, in an interview with Chris Bourke, Jarrett spoke openly about the magazine. “The only thing about Hot Licks that I believe is of value is that it’s an accurate reflection of its age, and what people thought about at the time,” he told Bourke. “I hate nostalgia. I’m not nostalgic about the magazine at all. It was good self-expression, and I really enjoyed it, but I really like being now, being current.”

With the end of Hot Licks, Jarrett and I went our separate ways. I returned to Wellington, taking up a six-month contract as a subeditor for the NZ Listener. Back in Auckland, I saw Jarrett a few times but our paths seldom crossed and, after I moved overseas, we lost touch.

My last memory was of seeing him on one of my short visits back – a concert in Auckland, probably 1984 or perhaps 1988, but I can’t be sure who was playing. I saw him across the room in the audience and caught his attention. There was that familiar boyish grin, a sparkle in his eye. We’d catch up, we said. But, damn it, we never did.

Roger Jarrett, Takapuna, July 1987 - photo by Chris Bourke

March 2000. I was in San Francisco when I heard the sad news.

On Jarrett’s death, one-time Split Enz member Mike Chunn wrote “Roger and his Hot Licks magazine believed in contemporary NZ music as a powerful cultural force. He dissected it, he lauded it, he exposed it, and he criticised it – all in good taste.”

The magazine was, as Walker now says, “the first serious music magazine we’d had. It gave a voice, in print, to the music business in New Zealand.”

Hot Licks arrived at a time when we weren’t sure of New Zealand’s place in the world and eagerly sought assurance. Look through archival news footage of that era and you’ll hear TV journalists asking visiting performers what they think of New Zealand, even as they first step onto the Auckland Airport tarmac.

Before Hot Licks, we lacked a frame of reference for the local music scene.

We thought that if it was a local act it wouldn’t be – couldn’t be – any good. So we booed musicians who would have been cheered in other places. Or we simply failed to turn up to see them, even when it was only a dollar to get in.

The 1980 Roger Jarrett hand-inked design for the first Propeller logo - Simon Grigg collection

Radio was little help, with local music getting next to no airplay. Remembering Split Enz’s early struggle for local recognition, Chunn puts it bluntly: “Broadcasting was stonewalled and managed by elderly middle class men with no taste.” That would change eventually, but Barry Jenkins’ Radio With Pictures wouldn’t arrive on TV until shortly after Hot Licks’ departure.

Chunn is also dismissive of the university campus underground circuit at that time. He credits Hot Licks, however, for giving “the young potent audience of 16 to 25-year-olds a focus”.

But Hot Licks wouldn’t have been half the magazine it was without Roger Jarrett. It is for this that he and his magazine deserve to be remembered – he believed that New Zealand music was worthy of recognition, not least by New Zealanders themselves.

Surf's up: Roger Jarrett in his element. - Bruce Jarvis

Read more: The Hot Licks covers

--

Thanks to those who helped me with comments and encouragement in writing this article: Roger Thornton Brown, Murray Cammick, Mike Chunn, Dick Frizzell, Grace Cardwell Scouller, Susan Templer and Rhys Walker.