Millie Bradfield with Lou Mati, bandleader and proprietor of the Polynesian Club, near Pitt and Beresford Streets, Auckland. - Photo by Merv Thomas, 1976

Once described as “NZ’s Naughtiest Nitery”, the Polynesian Club was a unique venue in Auckland during its 1950s heyday. The patrons on the dancefloor were a true cultural melting pot, the music ranging from Hawaiian-influenced popular tunes to swinging jazz, and – despite the rules around 6pm closing – the bar serving alcohol all night long. It was run by band leader, multi-instrumentalist, and club owner Lou Mati, who had emigrated from Tahiti. Many great musicians of the day were drawn to the “Poly” by the freedom to play whatever they liked. It all went remarkably smoothly until the early 1960s, when the club came to a nefarious and untimely end.

This photo of Karangahape Road in 1953 shows the windows of the club above street level, with signage reading: “Polynesian Dance. Entrance at the rear of the building.” - Archives New Zealand BABJ A680/1/3

The space where the Polynesian Club once operated is still visible, sitting on the first floor of the building next to the Pitt Street Pub (formerly the Naval and Family Hotel) on Karangahape Road and running through to Beresford Street on the other side.

There’s nothing to indicate that a century of musical events occured in the space, but it has a long history of musicians performing there, well before Lou Mati’s freewheeling reign as venue owner from the early 1940s to the early 60s.

The building was originally opened by the Fraternal Order of Foresters as a Foresters Hall in 1884 and was used for a range of activities: religious services, dance lessons, seances, public talks, and musical performances.

An advertisement in the Auckland Star, 8 May 1886.

In 1912, it became the Newton Picture Palace (aka Palace Theatre) which showed silent films, which were undoubtedly accompanied by musicians. The hall then reverted to a space that could be hired for public events. An Auckland Star ad on 9 April promised “A perfect floor, a wonderful orchestra, luxurious furnishings”. The venue lasted two years, including six months renamed as the Savoy Club Ballroom, before the management moved their dance to the Orange Hall.

On 12 April 1927, the Musical Box Cabaret opened in this space with Jack Rowe leading the Musical Box Five. In 1932, it became the Labour Party Hall (or just Labour Hall) and again had dances on nights when it wasn’t required for political activities. In March 1937, Lew Mati’s Royal Hawaiian Band began playing at the hall from 8-12pm on Wednesday nights.

Lou was actually born “Laurent Mati” in Tahiti in 1906, but over the years his first name shortened, with a variety of spellings: “Lalou,” “Lu,” “Lew,” or eventually just “Lou”. From 1925 onwards, he spent most of his time in New Zealand. His cousin Gus Lindsay recalled playing in Lou’s band in the early 1920s and says that they even played in the US at that time (Lindsay later led bands at the Orange Ballroom, Labour Hall, and Pt Chevalier Sailing Club).

Lou Mati joined the Royal Rarotongans, who toured Aotearoa extensively between 1924 and 1926 as part of the local touring circuit run by Australian promoters such as J C Williamson and Harry G Musgrave. In 1926, Mati married Hylda Mitchell, who came from a well-respected family in Rarotonga (though her mother was Tongan and her father was English).

The Mitchell Family, with Hylda second from the left. Photo: Wikitree.

In November of 1926, Mati began to advertise his services as a music teacher in the Auckland Star: “Lalou Mati, late Casino Theatre, Paris. Expert teacher banjo, mandolin, tenor banjo, ukulele, and guitar, at 144, Sly’s, Symonds St.” The suggestion that Lou had played in Paris is unsurprising given his international tours and Tahiti’s status as a colonial territory of France, although Tahitians weren’t given full French citizenship until 1946.

In March 1927, Lou began appearing with his “Tahitian Instrumental Quartet” and “Viaoleti Lutaligi, Premier Hula Hula Dancer” as part of a vaudeville variety show at the Britannia Theatre at Three Lamps, Ponsonby. The group played other nearby venues, including the Prince Edward Theatre (the Mercury Theatre).

From 1936-37, “L. Mati’s Hawaiian Band” had a residency at the Pt Chevalier Sailing Club, where the show included hula dancing and patrons were given leis to wear. He took part in similar nights at the New Romanos Cabaret on Karangahape Road (previously the Carlton Cabaret). Then in March, he found a long term home for his band when he began playing shows at the Labour Hall.

The initial run of Lou’s Hawaiian Band at the Labour Hall lasted for three years and cemented their place as one of the foremost acts playing Hawaiian-influenced music in a popular style, providing a bridge between Walter Smith’s band before them and subsequent acts such as Bill Sevesi and Bill Wolfgramm. However, the gig listings went quiet in 1941, before the opening of the Polynesian Dance Club was announced early the next year.

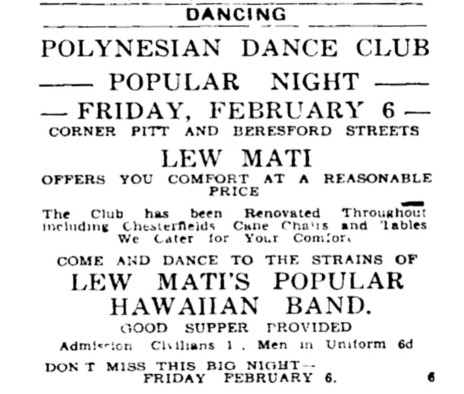

Auckland Star, 5 February 1942.

Lou and Hylda Mati used the Polynesian Club to bring styles of entertainment from their homelands directly into the heart of central Auckland, with Tahitian and Rarotongan dancers, as well as Polynesian-style food: “fish cooked in the Island fashion, mussels, pipis.”

By September 1942 the music was a mix of the “Island melodies and the latest swing numbers”, including such favourites as ‘Princess Pupule’, ‘Don’t Sit Under the Apple Tree’, ‘Johnny Doughboy’, ‘Manhattan Cocktail’, ‘Tangerine’, ‘Tahitian Moon’, ‘Tamure’. There were jitterbug competitions, cigarettes for sale, and Monte Carlo (gambling). Lou Mati led the band, playing “fascinating rhythms on his electric steel guitar” though within a few years he was confident enough in his group’s reputation that he dropped the mention of “Hawaiian” and instead took the more honest label of a “Tahitian band”.

Through the band, Mati was able to provide work for local Polynesian performers, and talented Māori musicians. He employed guitarist Mark Kahi for seven years, after which Kahi became the leading jazz guitarist in the country, playing on the radio with the Four Aces (Kahi, Frank Gibson Sr, Crombie Murdoch, George Campbell). Mati gave lessons to Kahi’s brother Tommy, who became a respected guitarist in the local scene and in Christchurch. The Polynesian Club was one of the first places you could hear the smooth voice of Māori/Tahitian singer George Tumahai.

Polynesian Club owners Lou and Hylda Mati are bottom right in the band photo. Pacific Islands Monthly, 1 February 1953.

In 1949, Mati became a New Zealand citizen and by the mid-1950s he and Hylda were living in a house within walking distance to the club, at 26 Seafield View Road in Grafton. As the decade progressed, it gradually became known as a late night spot where jazz musicians who worked in the city would have “a blow” once their paid shifts had finished for the evening, as trombone player Merv Thomas recalls:

“You’d get in for free and Lou sold alcohol – illegally of course. You could go up there with your horn and just sit in. He never paid anybody, it was just a place to go up and have a blow … I played up there with all sorts of people: Lyn Christie, Pem Shepherd, Lachie Jamieson. The music we played was all jazz, but it was always, of course, at a tempo that people could dance to. I don’t recall the place ever chocka with dancers, I think people came up to listen. And of course, because it was a place where you could get booze.”

Bernie Allen also played at the club and recalls that occasionally he’d get a small payment from Lou, but only grudgingly:

“Lou ran the place … he also served, he played saxophone too, but if it was going to be a busy night and he and Hylda were held up, he would hire someone to come in and play. And he’d say ‘you’re coming in Sat night and I’ll give you 7/6 shillings’ and you’d say ‘but the union rates for a gig are a guinea’ and Lou would say ‘oh but I’m not paying you for a gig. If you come in and play I’d give you seven and six.’ So you know, it was kind of like that … Halfway through the night, Lou would come up on the stand and no matter what we were playing, Lou would say ‘stop, we’ll do the Tahitian Conga now.’ He’d get on the drums and go into a pretty wild drum solo. Then a few Polynesian ladies would get out on the floor and shake their hips to do an informal dance. Then they’d finish and we’d go back to playing again.”

Dancers at the Polynesian Club. - Auckland Libraries 1269-E0146-09

The availability of alcohol gave the Polynesian Club a certain reputation and in 1954 a petition was submitted to Auckland Council to shut it down. The complainant, A H Dodd, said the club should be closed due to “obscene language”, offences against adjoining premises and even “orgies”. The NZ Observer sent along a correspondent to investigate and he entitled his article “NZ’s Naughtiest Nitery” (13 Oct 1954):

“The music is fast and jammy. The floor is full – but not flooded. You work your way past the coat counter where two hat checks girls (no hats, few coats) are too busily and happily jitterbugging with each other to notice you; past a couple of Māori youths playing a casual game of table tennis; past a girl in a yellow frock having a solitary game of darts. Where the bar would be in an overseas club is a bare supper counter and deserted tea urn. The crowd, on the dance floor and on its fringes, is like the music itself – downbeat jive, played with a zest and with a more languorous hum of Hawaiian guitar running through it. A good looking blonde is dancing with a young Māori, whose rhythm is considerably better than her own. A statuesque island girl wearing a black skirt, green blouse and very bored look goes by … The number finishes. ‘Now we’re going to do a foxtrot – no jitterbugging this time, please!’ a cheerful grey-haired man, grinning pleasantly, says over the microphone. The compere, whose ancestors sailed the Pacific in their canoes, is the part-time guitarist, part-time saxophonist in this five-piece orchestra.”

However, the article went on to deny that many “naughty” acts are going on in the club:

The idea that the Polynesian Club was a den of sin was undoubtedly driven partly by racism.

“The night I last visited the Polly was a Saturday night. There was not a drunk in the entire crowd – more than can be said for all the invitation-only affairs I have attended in commercial premises. The most common beverage was the tea drunk with decorum at supper. It is perfectly true, on the other hand, that in the darker corner a beer bottle or two would appear and disappear. Not all the liquid in the glasses here and there were orange pop. But what any honest detective, however, would have to admit was that there was less whisky consumed – far less – than at most police balls.”

The idea that the Polynesian Club was a den of sin was undoubtedly driven partly by racism. Bernie Allen was well aware of the reputation of the place at the time, but it generally didn’t match up with his experience:

“If you told people you were playing the Poly, they’d ask if you got out alive, but it was good fun. Hylda would get stuck into us musicians from time to time, but I enjoyed spending time with Mati and Hylda. They were good people. Lou ran the place really well. With Lou, you didn’t need a bouncer. He didn’t stand any crap.”

Allen reels off a long list of young musicians who played there before becoming central to the local scene, most notably the bebop saxophonist Bart Stokes, who ran the elite Auckland radio band before moving to the UK, and the aforementioned Lachie Jamieson, a recent returnee from the US where he played drums with Sonny Rollins, among many others. In Anna Hoffman’s autobiography Tales of Anna Hoffman (2009), she also mentions seeing Auckland pianist Billie Farnell playing at the club and gave a vibrant description of the crowd: “Young men with ducktail or DA hairdos, wearing stovepipe trousers were jive dancing with girls in full skirts and blouses, just like mine. They spun around displaying layers of petticoats, their ponytails flying free.”

Polynesian Club patrons in 1961, note the distinctive artwork along the back wall, stylish mid-century curtains, and beer bottle on the table. - Auckland Libraries 1269-E0145-34

Bernie Allen recalls that both Don Lylian and Phil Warren played drums at the club, before starting Prestige Promotions and touring many of New Zealand’s biggest acts. Equally important to the music scene was Harry M. Miller, who described his visits in his autobiography:

“On Sunday nights, the Polynesian was the place where local musicians gathered for jam sessions; the sort of place where, among a good crowd and under the influence of good jazz, you could feel at the centre of a very special world. I had the same feeling under more authentic influences, the first time I visited Ronnie Scott’s jazz club in London. But for the mid-1950s the Polynesian Club, tatty though it may have been, was a heady place in little old Auckland. One night, inspired by a reckless confidence in my sense of rhythm, I asked a drummer I knew if I could sit in for him during a simple set. Jazz or dance band drummers in those days usually seemed to be lugubrious, monosyllabic characters, coming alive only when they took solos which would sent them briefly demented. The fellow I knew had done his big solo for the night and seemed happy to pass his sticks and brushes to me. I cannot say I gave a distinguished performance but did all that was required for the small group and no one objected when I deputised on several further Sunday nights.”

Lou Mati (far right, on saxophone) at the Polynesian Club. Tony Ashby is the clarinettist. - Merv Thomas

Among those who played at the Polynesian Club were others who left music behind to become successful in other fields, such as John Daley who had a show in Australia “playing trumpet on roller skates” before he returned to New Zealand and became a compere on television. David Forman played trumpet at the club before he started the business training company which is named after him.

Bernie Allen believes it was this freedom to get up and play that made the club so appealing: “Young guys have to test themselves. When you’re that age, you’re testing yourself as to how good you are. You want to beat the next guy. Music shouldn’t be looked upon as a competitive sport, at that age you are competitive – you want to play faster, louder, higher … Nobody ran the band exactly. Usually Lou would yell out ‘Guys, start playing.’ Everyone would shuffle up to the stage and say ‘What are we going to play next? What key? How does the bridge go?’ Then you’d play. If a drummer didn’t turn up, Lou would play drums. His skills on the drums were pretty basic, but he could carry it. Hylda was the same on piano. Brian Spence’s brother Owen played regularly up there and he was quite a good saxophone player. I think he had a deal with Lou, so there’d be at least one musician to get the band together each night.”

Mauri Chan at the Polynesian Club, 1961. Chan went on to release a run of singles on the Zodiac label. - Auckland Libraries 1269-E0146-05

Unfortunately the good times didn’t last far into the 1960s. Allen found that the club had become a popular place for sailors and merchant seamen to congregate and this led to semi-regular fist fights:

“There were two boats that did the island trips – the Tofua [MV Tofua II} and the Matua – and God help you if you if those boats were in town at the same time – there was always war between the crews. I do recall stoushes up at the Poly. I recall one case where the police took both crews and lined them up, then took them all the way back down to the wharfs to be confined to quarters …

“This particular night we were playing away at the Poly and one of the guys says, ‘I’m going down for a drink’. He came screaming back over to us and said ‘We’ve got to get out of here, there’s blood all over the walls, there’s fighting downstairs like you wouldn’t believe.’ So we climbed out the window to the awnings of the shops on Karangahape Road and walked along to Prime’s Hardware Merchants and they had a ladder where you could get down most of the way. We were handing the horns down as we went. There were two American [Navy] destroyers in town and one of the guys was knifed and killed down there.”

The Polynesian Club closed soon afterward, though other nightlife did continue in the spot in later decades. There was a nightclub in the same spot during the 1990s called Club Polynz. In the 2000s, the space was finally converted to an office space.

A jam session at the 50th wedding anniversary of Polynesian Club proprietors Lou and Hylda Mati, 1976. Sitting in front are Don Branch (usually seen behind a drum kit), Derek Neville on clarinet, and Millie Bradfield. At the back, from left, are Bobby Griffiths on piano (usually a trumpeter), Bert Penney on bass, and Chuck Morgan and Johnny Bradfield on guitars. - Photo by Merv Thomas

Local musicians who played the Polynesian Club continued to feel a debt of gratitude towards Lou and Hylda Mati, reflected in the impressive turnout at their 50th wedding anniversary in 1976. The event even had band leader/trombonist Merv Thomas as its photographer.

Hylda passed away on 16 June 1991 aged 83, and Lou followed her in 1994, aged 88. His occupation, to the end, was listed as (Retired) Musician.