Crombie Murdoch

From a Southland farm to the Auckland Town Hall stage with Nat King Cole, Dave Brubeck and others, pianist Crombie Murdoch – aka “the quiet man of jazz” – made his mark in music without fuss or bother. His 1950s ditty about the Hokianga Harbour dolphin, ‘Opo the Crazy Dolphin’, was an overnight success, but its omnipresence embarrassed him, as jazz was his great love and primary focus.

Murdoch eased into the Auckland music scene as a young man in the 1940s, and quickly became an admired and in-demand fixture as bandleader, arranger, and studio pianist. He was the accompanist of choice for leading vocalists Mavis Rivers, Pat McMinn, Esme Stephens, and Coral Cummins, in live performance as well as the recording studio.

Auckland's new song hit ... "Taniwha blues", recorded by Pat McMinn, "The Stardusters" and the Crombie Murdoch Trio (popular TANZA recording artists). Taniwha Blue - it blues as it washes [1956]

Photo credit:

Alexander Turnbull Library

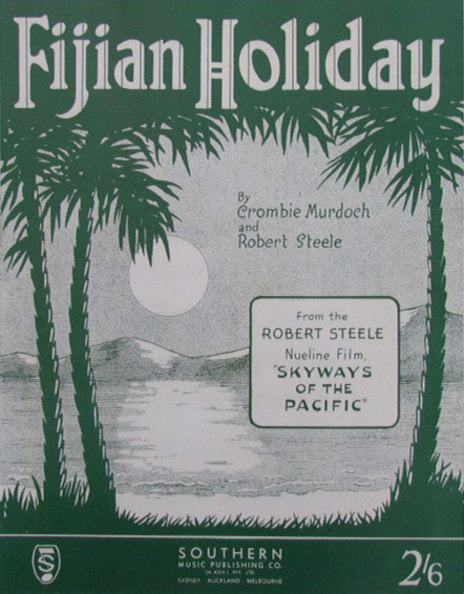

The sheet music for 'Fijian Holiday', a 1951 hit on the Tanza label for Mavis

Photo credit:

Grant Gillanders Collection

Ted Croad’s band at the Orange Coronation Hall, Auckland, late 1940s. From left: Crombie Murdoch, piano; Pat McMinn, vocals; Eddie Croad, drums; Ted Croad; George Campbell, bass; Tommy Simpson, tenor; unknown trumpet; Jim Watters, tenor; Lou Campbell, trumpet; Jim Warren, trumpet; Gordon Lanigan, alto; unknown trombone and tenor.

Photo credit:

Jim Warren collection

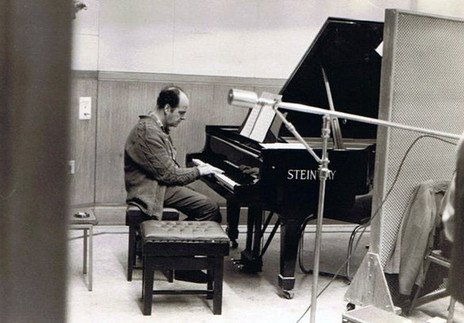

Crombie Murdoch performs in the 1ZB Radio Theatre, Auckland, late 1970s

Dale Alderton, Crombie Murdoch, Julian Lee.

Photo credit:

Stebbing archive

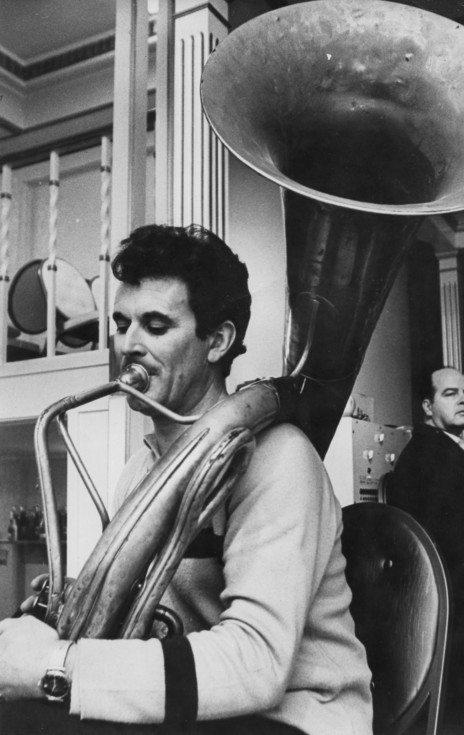

Merv Thomas having a blow; on the far right is pianist Crombie Murdoch.

Photo credit:

Merv Thomas Collection

Crombie Murdoch Trio - Waltz For Debby

Crombie Murdoch at the piano, with Colin Martin taking a saxophone solo, in Whangamata a few days after the Tangiwai tragedy, 1953. Pat McMinn at left.

Photo credit:

Pat McMinn Collection

Crombie Murdoch at the Hi-Diddle Griddle on K Road, Auckland, late 1950s.

Pat McMinn with the Crombie Murdoch Trio - 'I Want A Hippopotamus For Christmas'

“The Kentuckian Song”: Dorothy Brannigan & Buster Keane with Crombie Murdoch and His Rhythm (Tanza)

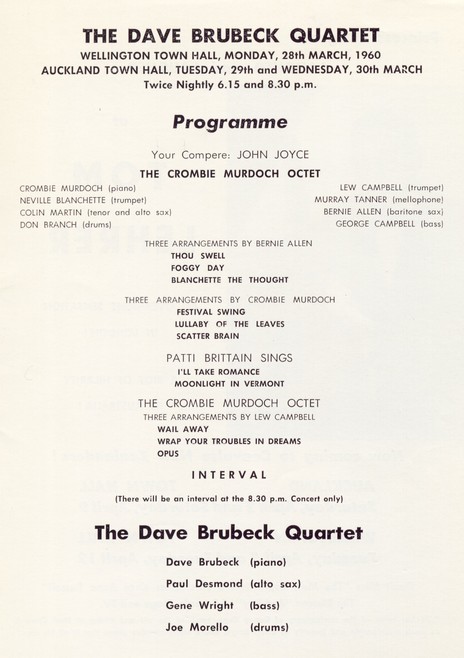

The programme for the Dave Brubeck Quartet's concerts in Auckland and Wellington in March 1960, showing the items played by the support act: the Crombie Murdoch Octet.

Photo credit:

Chris Bourke collection

Mavis Rivers with the Crombie Murdoch Trio during a television show in the NZBC studios in Shortland Street, Auckland, 1963. From left: Lester Still, Mavis Rivers, Crombie Murdoch, and Don Branch. Photo taken by Alton Francis.

Photo credit:

Auckland Libraries Heritage Collections Footprints 02523

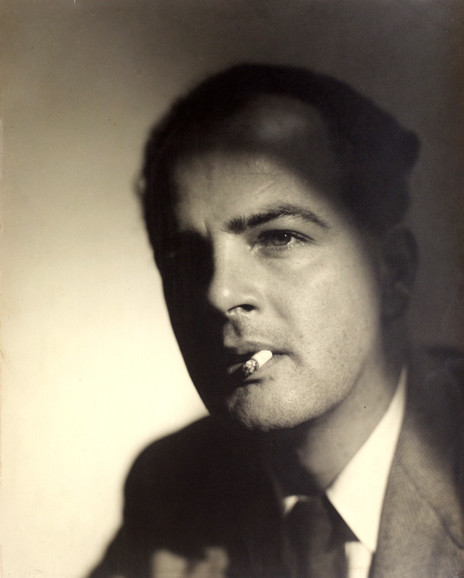

Crombie Murdoch, 1952.

Photo credit:

Clifton Firth, Sir George Grey Special Collections, Auckland Libraries 34-321.

Fijian Holiday”: Bill Wolfgramm’s Hawaiians with vocalist Daphne Walker, written by Crombie Murdoch (Tanza).

Julian Lee on saxophone at the Auckland Swing Club, late 1940s, with drummer Neil Dunningham, bassist Thomson Yandall, and pianist Crombie Murdoch.

Photo credit:

Dennis Huggard collection

Crombie Murdoch with US singer June Christy, who visited Auckland in 1955 with Nat King Cole.

Crombie Murdoch in the 1ZB Radio Theatre, Auckland, late 1970s.

Crombie Murdoch at the piano, with Thomson Yandall on bass and guitarist Ray Gunter.

Crombie Murdoch conducting his own band, with George Campbell on bass and Don Branch on drums.

Crombie Murdoch at the piano for a 1946 session with, from left, Frank Gurr, Jim Warren and Doug Kelly.

Photo credit:

Photo by Peter Lishman/Jim Warren collection

Mavis Rivers with Crombie Murdoch at the 1ZB Radio Theatre, Durham Lane West, Auckland. The band includes Frank Gibson Sr. on drums

Photo credit:

Grant Gillanders Collection

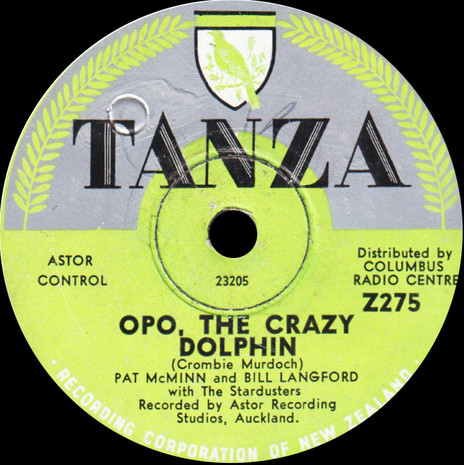

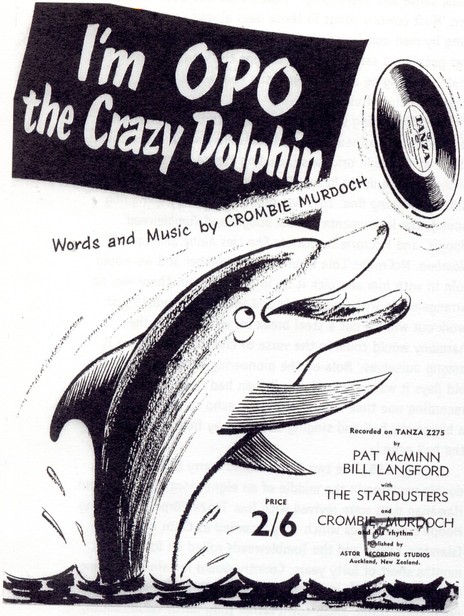

Pat McMinn and Bill Langford with The Stardusters - Opo, the Crazy Dolphin, written by Crombie Murdoch (Tanza)

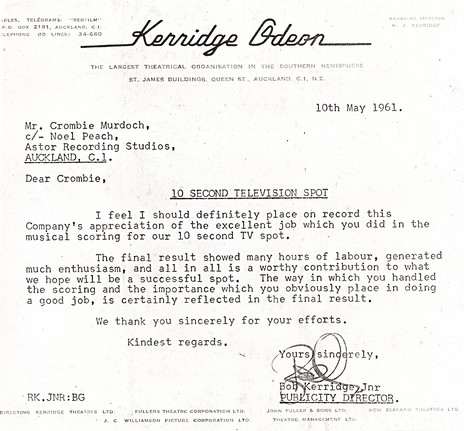

A letter of appreciation to Crombie Murdoch from Bob Kerridge Jr, son of the impresario Sir Robert Kerridge.

Under the Red Moon of the Pampas: Crombie Murdoch – His Piano and His Orchestra (Stebbing).

‘Opo the Crazy Dolphin’, recorded by Pat McMinn with the Stardusters, was written by jazz pianist Crombie Murdoch and released on Tanza in 1956.

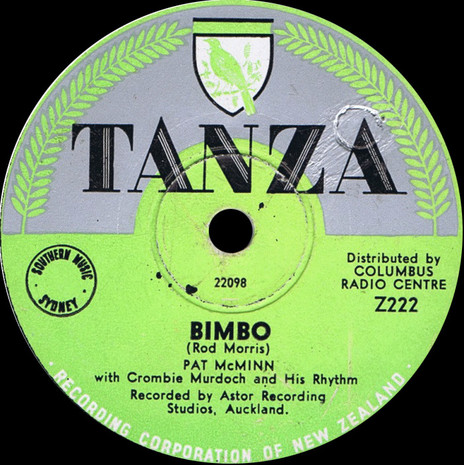

Pat McMinn with Crombie Murdoch and His Rhythm - Bimbo (Tanza)

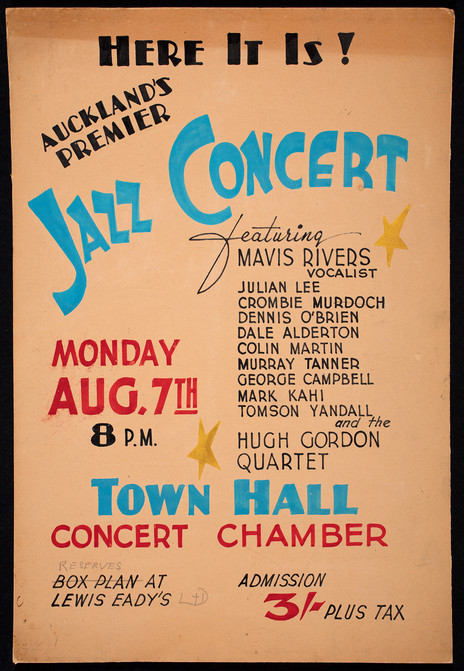

Auckland's Premier Jazz Concert, Auckland Town Hall Concert Chamber, featuring Mavis Rivers, Crombie Murdoch, Dennis O'Brien, Dale Alderton, Colin Martin, Murray Tanner, George Campbell, Mark Kahi, Thomson Yandall and the Hugh Gordon Quartet. - Auckland War Memorial Museum, EPH-PT-15-1_001

Crombie Murdoch acetate - 'Laura'

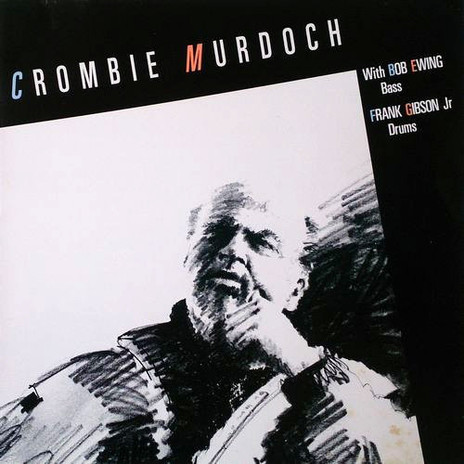

Crombie Murdoch's 1988 album on Ode Records, with Bob Ewing on bass and Frank Gibson Jr on drums.

Merv Thomas, far right, in the Eliza Keil band. Beside him is trombonist Dale Alderton; Crombie Murdoch is seated, alongside trumpeter Murray Tanner.

Photo credit:

Merv Thomas Collection

Links: