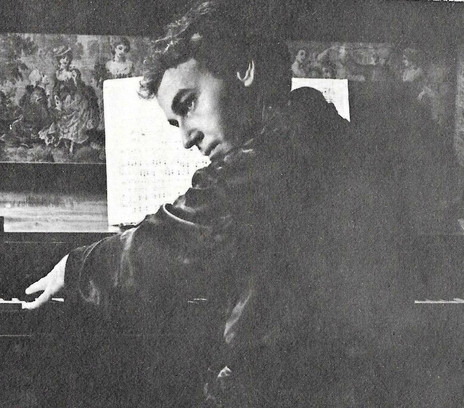

Farnell had a couple of aunts who owned baby grand pianos, and he would watch them playing popular tunes of the 1930s such as ‘Painting the Clouds with Sunshine’. He did his best to watch their hands and pick up what he could. His father was against the idea of having a piano, but eventually his mother snuck a pianola into their house when her husband wasn’t looking (he didn’t notice for a month).

Pianolas or “player pianos” play tunes off rolls of paper with holes punched in them, which cause the keys to depress as they scroll around. Farnell would pedal it slowly so he could watch the keys go up and down, then mark them with his mother’s make-up to keep track of the notes.

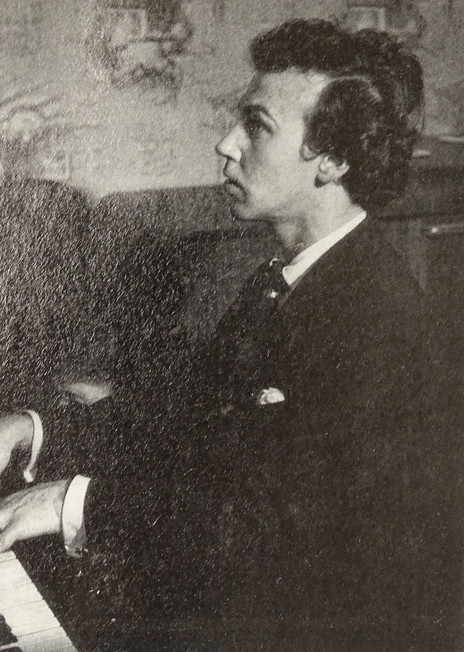

Farnell became proficient enough that he could play songs he heard off the radio. He started his own band at age 14 to perform at Rongotai College social events, mixing modern hits with classic ragtime numbers such as ‘Kitten on the Keys’ and ‘Twelfth Street Rag’ before moving on a few years later to the Pines nightclub.

In the holidays, his family often left Wellington to visit his grandfather in Auckland. He saw shows at the St James Theatre and the Civic, where Freda Stark – an aunt through marriage – had previously performed.

Around 1951, Farnell went for a weekend visit to Auckland and was enlisted for a band by Phil Warren, who at the time was a drummer. Warren needed a pianist for his band’s gig at the Town and Country Roadhouse in Oratia, a venue opened by Marge Harré, based on roadhouses in the US. Warren gave Farnell a ride to their first gig at the Town and Country on the back of his motorbike, though this meant holding onto the drums as best they could for the long drive out West.

At the time, the Waitakere ranges had a sprinkling of popular entertainment venues such as the Dutch Kiwi, Back of the Moon, and the Toby Jug in Titirangi. They were far enough out of town that punters were able to get away with some “sly grogging”, though they were often raided by police. The restaurants would call each other if police were doing the rounds. Patrons at the roadhouse would quickly be warned to hide their booze and Harré’s 11-year-old son would run upstairs and slide out through the window onto the roof so he could lower an “Alcoholic Liquor Prohibited” sign over the main entrance.

It wasn’t a salubrious music environment, but Farnell finally saw a chance to fulfil his aspiration to play in the style of his idols, Frankie Carle at New York’s Waldorf Astoria and Billy Mayerl at London’s Savoy. He relocated to Auckland permanently, working wherever he could, sometimes at illegal establishments that flaunted the alcohol laws of the time.

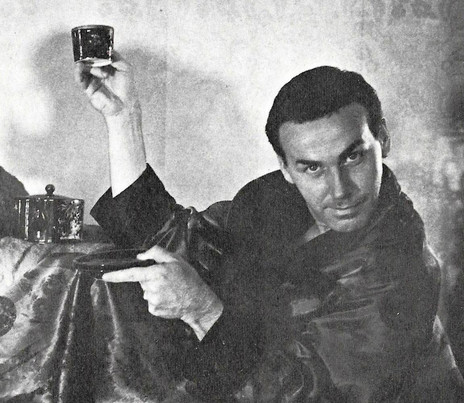

In 1955, Farnell took up a job at the newly opened El Morocco restaurant, on the corner of Wellesley and Federal Streets. He would provide backing music for singer Kay Reilly (Miss Western Springs), performing songs by Cole Porter and George and Ira Gershwin while people ate dinner and surreptitiously drank wine served in teapots. The interior was given a desert look with a tent and sand on the floor, while a person in a kitsch North African costume stood outside the front door to lure customers.

“I said to my mother ‘I’m the manager of the El Morocco tonight’. She said, ‘I don’t like the sound of that’.”

In an interview for the Queer Stories Our Fathers Never Told Us oral history project (2011), Farnell spoke of how his work as pianist at the establishment led him to falling foul of the law:

“I was playing the piano and Leon Aldridge who owned the place said to me this particular night ‘I’m going to have the night off; I’ll leave you in charge.’ … I thought ‘Oh, I’m coming up in the world.’ So I rang my mother. I said to my mother ‘I’m the manager of the El Morocco tonight’. She said, ‘I don’t like the sound of that’. She said, ‘you’d better come back’. I’d only just left college. And anyway, a man came up to the piano. He said, ‘Can you tell me who is in charge, who the manager is here?’ I said, ‘It’s me’. He said ‘right, you’re the man we’re looking for’. And it was down the stairs and into the Black Mariah [police van]. They were pretty heavy. They were looking for drink in the place.

“Another night they came, and it was upstairs and downstairs. And we had a dumb waiter … It [brought] the food up and down into the restaurant. And Leon said to me ‘oh god, take this’ and it was a box of Dewar’s Whiskey, a wooden box with all the drink in it, you know. I thought ‘what am I going to do with this?’ So, I stuck it in the dumb waiter, and I jammed it between two floors … the police were so angry they got an axe. They axed the walls … and Leon went to jail for three months for selling liquor.”

The police subsequently tried to convict Farnell, claiming that he kept alcohol in his piano stool and got the waiters to sell it to the customers for him. Fortunately, his lawyer had him bring his piano stool to the hearing and was able to show the court that it had no compartment where alcohol could have been hidden.

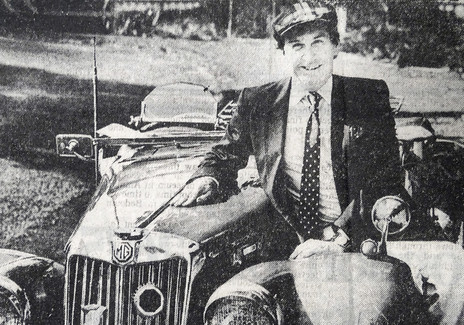

At the Town and Country club Farnell had played a Collard & Collard piano, but the instrument didn’t handle the heavy use of being a nightclub instrument for two years running. When he wanted a new piano, he purchased a gold painted Blüthner grand.

Farnell didn’t stop there and continued to keep an eye out for new pianos that were on sale at an attractive price. He managed to get a smaller grand piano, which had been left behind by the Royal Yacht Britannia (it was accidently drenched and left ashore). He squeezed it into his apartment by standing it on top of the Blüthner. The smaller piano still met its watery fate after Farnell eventually resold it: the new owner shipped it to London, but it slipped off the hook while being unloaded and fell into the River Thames. Farnell later bought a Steinway, which he painted gold to keep up appearances.

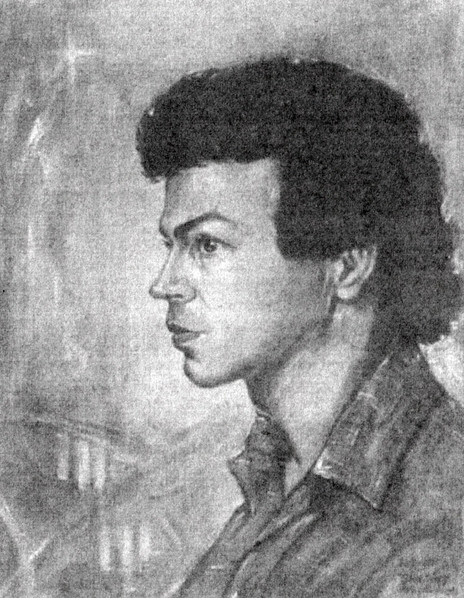

Around 1960, Farnell became friends with another flamboyant figure on the Auckland scene, Anna Hoffman. In her autobiography Tales of Anna Hoffman, she recounts their first meeting at Begg’s music store on Queen Street and how she was captivated by his friendly manner and impressive style:

“His appearance was somewhat startling for those times. He had shoulder-length black curly hair with a red felt beret, pinned with a glittering antique brooch on the side of his head. Slung over his shoulder was a lady’s handbag. In those days this would not only be wildly eccentric but almost indictable. I stood transfixed.”

This account contrasts with Farnell’s own description of how he met Hoffman. On more than one occasion he insisted that they were both trapeze artists in a circus.

After meeting her at the music store, Hoffman writes that Farnell took her back to his apartment, where he played her Beethoven’s ‘Moonlight Sonata’ and told her a fantastical story of his mother’s life in New York, which involved her playing for the Hotel Waldorf rooftop band and becoming romantically involved with millionaire “Diamond” Jim Brady. The truth of this tale is hard to verify, though it is true that Farnell was a naturalised US citizen though his mother.

His apartment was filled with object d’art: a stuffed crocodile, a polar bear skin, china cherubs, and a frog beside a Fabergé pig.

Hoffman described his apartment at the time as being filled to the brim with “wonderful and exotic object d’art” which included “a stuffed crocodile lying on an antique chaise, a polar bear skin on the floor, china cherubs on the wall, and a frog nestled next to a Fabergé pig.” By this stage, Farnell was playing at various venues across the city. Hoffman captured the scene at the Polynesian Club, of Karangahape Road, where Farnell showed that he was equally adept at playing modern rock’n’roll:

“The Polynesian dancehall known as the Poly was a large dimly lit low room with a low ceiling at the end of a long passage. Young men with ducktail or DA hairdos, wearing stovepipe trousers were jive dancing with girls in full skirts and blouses, just like mine. They spun around displaying layers of petticoats, their ponytails flying free ... As my eyes accustomed to the dim red light, I saw Billy Farnell playing at the piano. He smiled and raised his hand high in a wave without missing a beat. He was wearing rings on every finger, and I could’ve sworn he had on make-up.”

In 1958, Farnell began working for the legendary restaurateur Bob Sell at his newly opened dine and dance nightclub, La Boheme. Sell didn’t want diners to be disturbed by having a full band with bass guitar and drums, so Farnell adopted a solo piano style that covered the whole range of the keyboard. He was influenced by recordings he’d heard by Carmen Cavallero, who played light classical music with an audacious style, stretching chords across the whole keyboard by using sweeping arpeggios, often ranging over several octaves. This approach allowed Farnell to keep a melody line flowing, while filling in the bottom end, which a rhythm section usually would have provided.

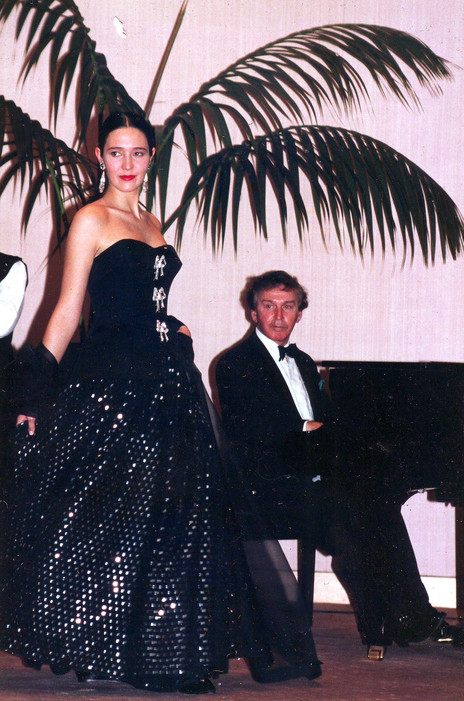

In 1959, Sell opened a new nightclub, The Colony, and enlisted Farnell to perform in the house band on Saturday nights along with Bruce King on drums and Les Still on bass. Farnell would be called upon to back a wide range of singers, including jazz crooner Ricky May and rising stars Kiri Te Kanawa and Lynne Cantlon. The patrons would eat their meals to light accompaniment then get up to dance before the night’s floorshow began at midnight.

In 1960, Playdate editor Des Dubbelt caught The Colony in full swing:

“The Colony is what is known in the trade as a plushery – the padded cell look, in satin. The DeMille decor, the low lighting, the appetite-whetting food and the music of the Billy Farnell combo for dancing – all this makes a plain girl look attractive and an attractive one a knockout.”

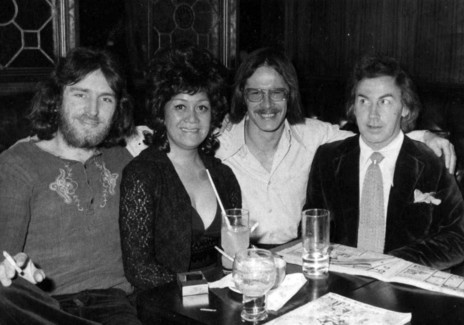

Farnell’s work during the 1960s took him across the breadth of the city and saw him play a wide variety of musical styles. One weekend, he might be appearing at audacious dine and dance venue the Hi Diddle Griddle on Karangahape Road; the next he would be joining Ricky Camden’s Afro-Cuban band The Featurettes for a series of concerts at the Auckland Town Hall and accompanying live broadcasts on 1YA Radio.

Farnell’s 18-year run at La Boheme finally came to an end in 1976 when the business was put into receivership. During his final years there, he backed rising singer Lea Wyber (Lea Maalfrid).

After La Boheme, Farnell immediately took up a residency at Bonaparte’s restaurant on Victoria Street, owned by Lada Ourednik. Max Cryer marked the occasion by penning a glowing profile of Farnell’s career up to that point in the NZ Herald:

According to Max Cryer, Daniel Barenboim once joined Farnell at the piano “for a jazz jam lasting three hours.”

“A wizard on the ivories, Billy’s memory for customers and the tunes they liked was a byword at the Boheme. The moment a customer walked in the door, Billy would recall what tune he had requested before, no matter how many months between visits … Classical musician Daniel Barenboim once got up from his dinner, asked permission to join Billie at the keys, and joined him for a jazz jam lasting three hours ... Billie can converse by the hour while his fingers never miss a note and anything he doesn’t know he’ll improvise so well that no one will know the difference.”

It was while working at Bonaparte’s that Farnell first met his long-time partner, chef and restaurant manager, Russell Green. In 2008 Green told the NZ Herald that Farnell’s reputation preceded him:

“I think I was about 11 or 12, and I remember reading this story about Billie in a woman’s magazine. He was a mad collector, and it talked about all the things he had in this wonderful home and some of the great musicians he’d met, people like Nat King Cole, Count Basie, and the Ink Spots. When I came to Auckland, I met people who knew him, and I even got a job with him, but I never realised who he was until I went to his house and recognised it. To have eventually met him and to now have been living together for 20 years, well, it’s quite amazing really, isn’t it?”

During the 1980s, Farnell was busier than ever, playing nights at Bonaparte’s, lunches at Sardi’s restaurant in Queens Arcade, afternoon teas at the Regent, and Sundays at Delmonico’s inside Hotel DeBretts on High Street. He filled in occasionally with other bands, such as the Wentworth Brewster jazz combo.

In 2005, Green and Farnell worked together to undertake one of their longest-running ventures. One of Green’s friends had a space at the bottom of town on Anzac Ave which he was willing to rent out for only $250 per week, since the building was set to be demolished. This led to the opening of Shanghai Lil’s, which was decorated with many of the antiques the pair had collected over the years.

After the building was demolished, Green chanced upon a similarly underutilised space, the Birdcage pub next to Victoria Park market. The new Shanghai Lil’s opened in the corner bar and soon gathered a cult following, becoming a must-visit drinking spot for visiting stars, such as Ryan Gosling and Sir Ian McKellen. After four years it was closed to allow work to take place on the Victoria Park tunnel. Shanghai Lil’s then reopened in 2009 as a restaurant in Parnell, but Green missed being out front with the customers so relocated it to Ponsonby Road and once more it became a bar.

Farnell was a regular performer at Shanghai Lil’s over the years – especially during its time on Ponsonby Road, when he played three nights a week. It then moved to Karangahape Road and became a combined operation with Bamboo Tiger. Farnell kept up regular gigs there, often performing with vocalist Jessie Le Marie.

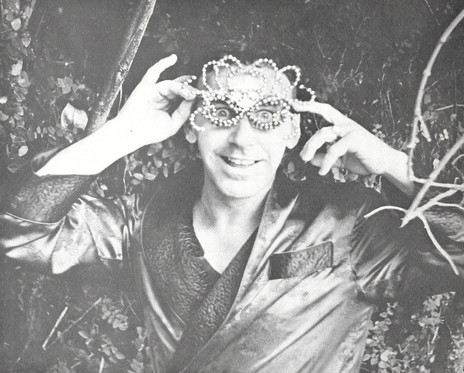

Farnell’s long career as a performer was recognised in 2016 by the Variety Artists Club of New Zealand, who gave him a Scroll of Honour. Farnell’s prodigious talent and fabulous persona had seen his career through decades of changing musical currents and the persistent homophobic bias within New Zealand society. He kept playing regardless and drew customers in with his flamboyant fashion sense and ease at the piano, allowing a rippling arpeggio to cascade across the keys or leaning in, emphasising a chord.

Billie Farnell passed away in February 2022. He was a showman to the last, a shining star of Auckland nightlife who will be sorely missed.