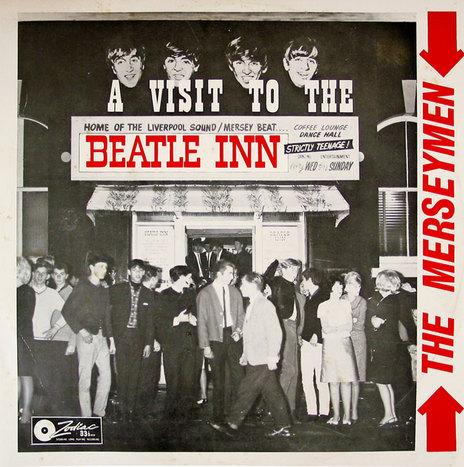

The Beatle Inn on Little Queen Street was the project of the likeable rogue and entrepreneur Phil Warren of Prestige Promotions. Never one to miss a commercial entertainment opportunity, Warren opened his Beatle Inn in 1964 on Little Queen St, a short strip which ran parallel to Queen Street.

When Warren spoke to the Listener in 1984 about the Beatles’ visit to New Zealand, he was unashamed about his opportunism: “My involvement, and I could see what was going on, was to cash in on the craze, which we did with the opening of the Beatle Inn in Auckland, in a street called Little Queen Street in [what became] the Downtown area. It held about 300 people, and we opened it Wednesday through Sunday nights at various hours and also at lunchtimes. We had a restricted policy on it, in that it was an R18 policy – no one over the age of 18 was permitted, and that was quite a gimmick.

“Of course, bands sprung up all over the country as Beatle imitators, and I think we had the best. We put together a group called The Merseymen and they played the Beatle hits and other songs in that idiom … The whole room was done out in murals and blow-up pictures of The Beatles. It was an enormously successful room and I was just one of many many people that took advantage of the Beatles’ craze.”

The Beatle Inn was ours: no one over 18 was allowed in, aside from musicians like The Merseymen

The Beatle Inn was small but that was important when you were young and hormonal: you could get close to the opposite sex.

And the band.

The Inn was ours: no one over 18 was allowed in, aside from musicians like The Merseymen.

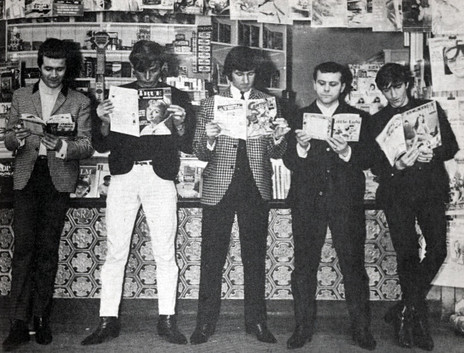

The Merseymen – which first played live there on 1 April 1964, according to Playdate magazine in a profile that October – were lead guitarist Bob Paris, rhythm guitarist Dave Moan, and singer Mike Leyton (Mike Puddyfoot who took his stage name from the British pop singer/actor Johnny Leyton). Moan and Leyton were Londoners so had considerable cachet in the British-obsessed pop scene at the time. Moan (pronounced Mow-ann) had played with Johnny Kidd and the Pirates and toured with Gene Vincent.

The bassist was Wellington’s Jim Newton (later replaced by Ian McIntyre) and the drummer Jett Rink.

Of them all, Jett – who had the longest hair – would become the most well-known. He was Liverpool-born John Taite who could claim to have actually seen The Beatles. He would adopt the name Dylan Taite and become – alongside Dr Rock (the late Barry Jenkin) and later Karyn Hay – one of this country’s most well-known music presenters and interviewers on television.

He had taken his stage name from the James Dean character in the 1956 film Giant. Dean was killed in a car crash before shooting finished, so the name had a kind of cool but doomed heroism.

Paris was a seriously good rock’n’roll guitarist who’d come up with the music in the late 1950s. His Bob Paris Combo had played Auckland’s Jive Centre in 1958 and backed Johnny Devlin, so turning his hand to The Beatles and British Invasion style – which emerged from similar rock’n’roll sources – came easily.

He had also been in studios to record an EP and singles with the Combo, and an EP and string of singles under his own name on La Gloria and Philips. Paris knew his way around the recording process.

Paris and Rink/Taite were of The Beatles’ age (early 20s) or a little older, their formative musical influences pre-dating the emerging Liverpool sound.

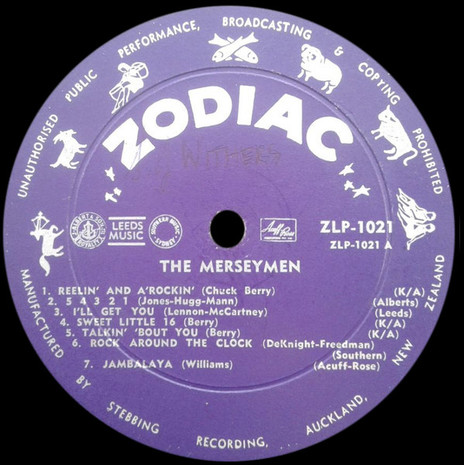

It was no surprise then that The Merseymen’s sole album, A Visit to the Beatle Inn – recorded in a day, in a garage, according to Roger Watkins’ Hostage to the Beat – reflected that earlier era more than the British sounds of the moment.

What’s interesting about their album on Stebbings’ Zodiac label is what isn’t on it as much as what is. By the time it was recorded The Beatles had released two albums – Please Please Me and With The Beatles – and singles which, with the B-sides, hadn’t appeared on either.

For the Merseymen album, there was a swag of Lennon and McCartney-flavoured tunes to choose from

So there was a swag of Lennon and McCartney-flavoured tunes to choose from, especially for a band called The Merseymen who played at a place called the Beatle Inn.

However the only one they picked was The Beatles’ lesser ‘I’ll Get You’, the B-side of ‘She Loves You’ (“Imagine I’m in love with you, it’s easy ’cause it’s true”). But they drained the energy out of it.

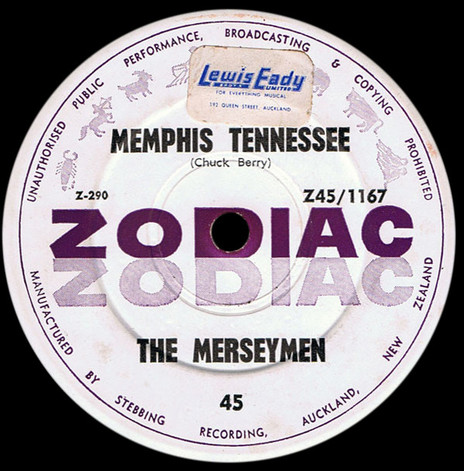

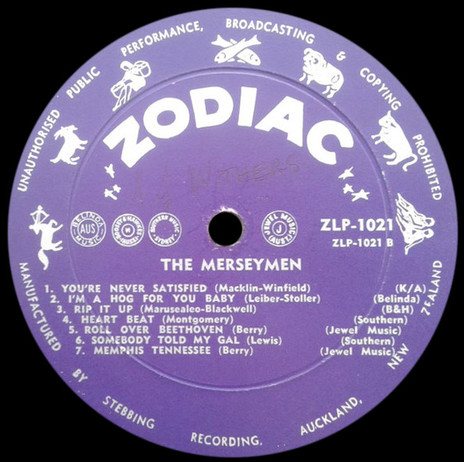

Elsewhere they covered Chuck Berry’s ‘Roll Over Beethoven’ which The Beatles had also done. But – perhaps showing their age and the earlier rock’n’roll culture they’d come through – chose Buddy Holly’s ‘Heartbeat’, Little Richard’s ‘Rip It Up’, more by Berry (‘Sweet Little Sixteen’, ‘Memphis Tennessee’, ‘Reelin’ and a Rockin’ and ‘Talkin’ Bout You’) and Bill Haley’s ‘Rock Around the Clock’ which was almost a decade old.

Hank Williams’ ‘Jambalaya’ was even older but given a smart Merseybeat treatment.

More recent songs were Manfred Mann’s ‘5-4-3-2-1’ from earlier in 1964 and ‘Somebody Told My Girl’, a clever facsimile of the Mersey sound by jobbing British songwriters John Carter and Ken Lewis (who became the Ivy League and wrote hits for Herman’s Hermits, the Flower Pot Men and many others).

The most unusual choice was Leiber-Stoller’s little known ‘I’m a Hog For Your Love’ but the most interesting cover was the obscure ‘You’re Never Satisfied’, a 1962 American non-hit by Richard Macklin and John Winfield (as Rick and Johnny) which is given a fine Searchers-like jangle.

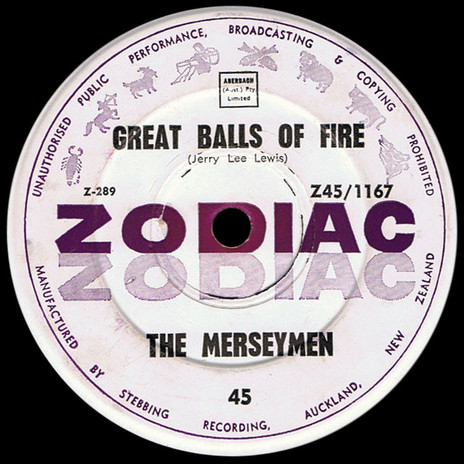

Because of their profile at the Beatle Inn, a few singles were spun off the album: ‘Memphis Tennessee’ (backed with Jerry Lee Lewis’s ‘Great Balls of Fire’), ‘Jambalaya’ (with ‘Maybellene’) and Chuck Berry’s ‘Talkin’ Bout You’ (b/w Huey ‘Piano’ Smith’s late 50s New Orleans R’n’B rocker ‘Don’t You Just Know It’).

There was some modest sales success for the album and singles, and the band’s profile rose through appearances on television and a live-to-air radio slot.

In the manner of pop journalism at the time, Playdate reported “The Merseymen have a great sense of fun, both on and off duty. Their casual air and their love of ‘goofing it up’ has all the zest and spontaneity of those four lads from Liverpool who call themselves ‘Beatles’.”

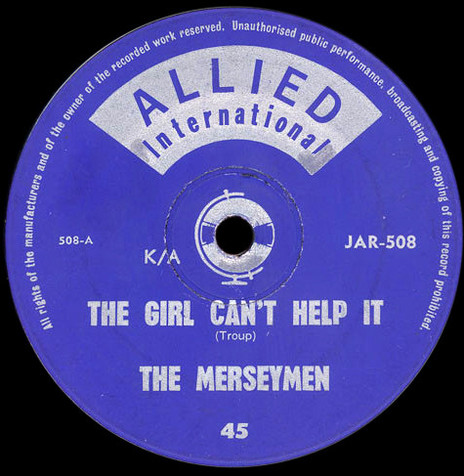

They went on the road around the country with Manfred Mann, the Kinks and Honeycombs on a package tour with Tommy Adderley and in 1965 released a couple of singles – Little Richards’ ‘The Girl Can’t Help It’/’Just a Little Bit’ and – oddly – Peter Cape’s local vernacular song ‘Down the Hall on Saturday Night’/’It’s Alright’.

But it wasn’t destined to last, the band broke up in 1965: Rink/Taite went to Christchurch and got serious about a career in journalism; Leyton joined Sounds (formerly Sounds (Auckland) Unlimited) and eventually moved to Australia with his wife, the singer Lyn Barnett; Paris remained in the music business in Auckland up until his death in 1994. Moan went on to run a very successful printing business.

The Beatle Inn had an even shorter life, it closed in early 1965.

That block in downtown Auckland – which included the once beautiful Oxford cinema which had become a flea-pit by the mid-60s and an underground games centre on the Queen St side – has long since been demolished in favour of glittering high-rises and retail centres opposite the old Post Office (now Britomart Station).

But for that brief period in the first year of Beatlemania, The Merseymen and the Beatle Inn captured the spirit of Beatle-obsessed youth before adolescence faded and adulthood started to impose itself.

I remember what I wore the first time: a black polo neck sweater, just like John, Paul, George and Ringo

I was very young at the time – The Beatles played in Auckland on my 13th birthday in June 1964 – so only went to the Beatle Inn twice. But I remember what I wore the first time: a black polo neck sweater (just like John, Paul, George and Ringo), some fairly ordinary dark trousers and my black school shoes, because I had no others.

The collarless corduroy Beatle jacket my mother would make me was still some months away, the Beatle boots years off. Although I did inherit a pair from Ian White (the older brother of Peter who became Lez White in Th’ Dudes). He had very big feet so I had to wear my thick woollen rugby socks, and still I slid around in them.

The look was important and I remember at the Beatle Inn and other clubs like the Platterack, Shiralee, and the Top 20 the girls really made an effort to dress up and look the part.

Almost as much as the boys. We grew our hair, adopted the British style and soaked up that music which just kept coming from Liverpool, London, Manchester and, soon enough, from Christchurch, Wellington, Auckland ...

It was thrilling being young and part of a global tribe of like-minded people listening to the same songs and willing to argue about who was the better drummer, Ringo or Charlie.

To borrow from the British poet William Wordsworth, “Bliss was it in that dawn to be alive. But to be young was very heaven!”

And in 1964, even in remote Auckland with a band called The Merseymen at the Beatle Inn, heaven had a great soundtrack.