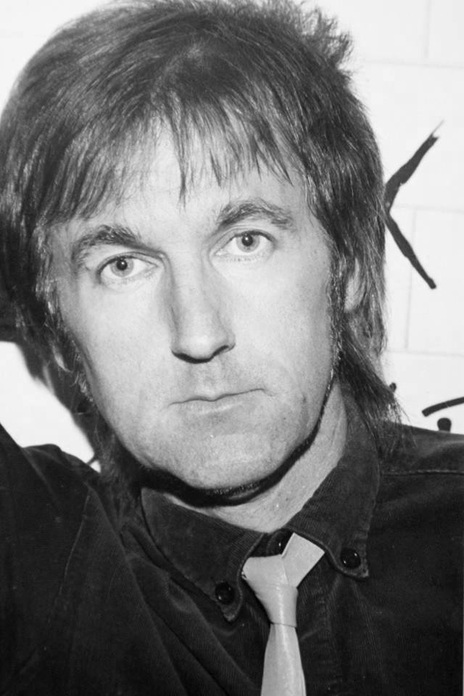

That was how a lot of people of a certain age first came to know Dylan Taite, ranting away in the TV3 lift at the arse end of Nightline about life and music. “Never have we had. So much garbage to choose from,” was one particularly prescient nugget of wisdom that’s only gotten truer with time. However, at that point the Liverpudlian Taite was a 30-year veteran of music journalism on the telly. And he pretty much kicked arse all three decades.

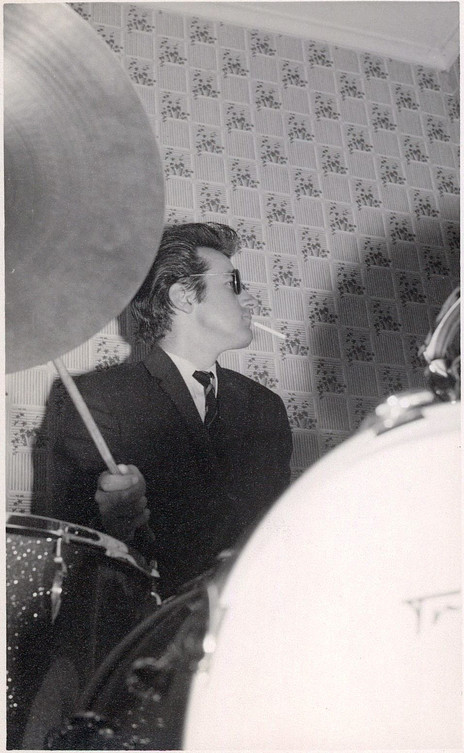

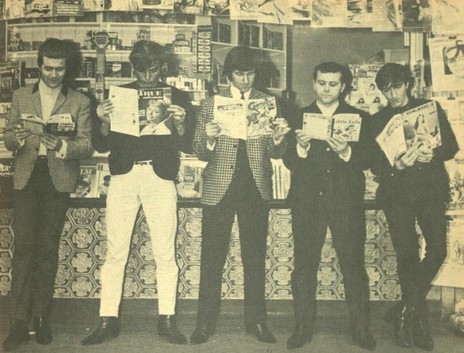

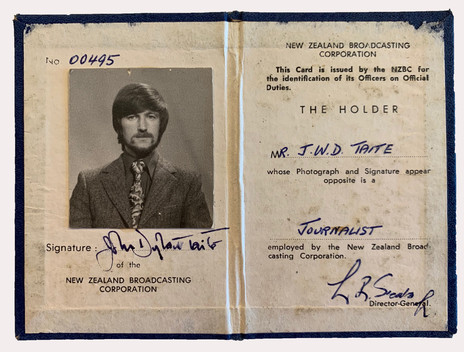

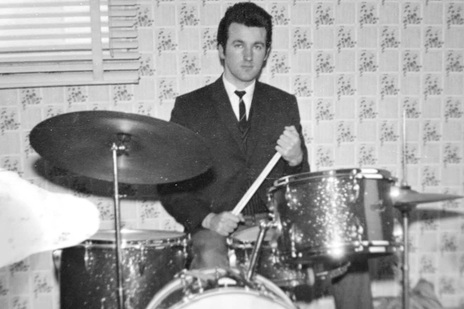

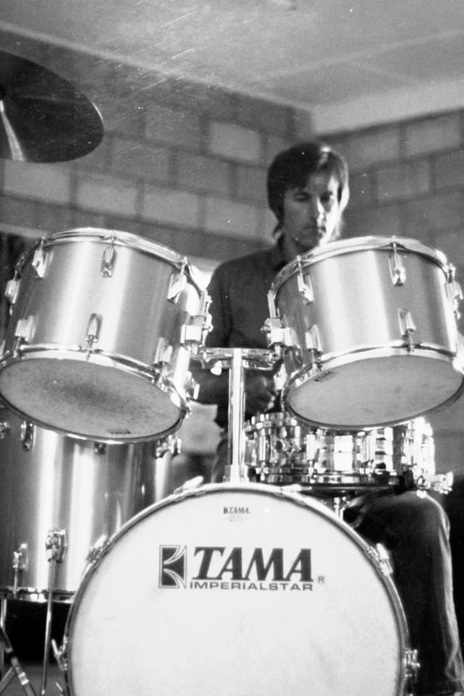

He rose to prominence in New Zealand initially as Jet Rink, the drummer for The Merseymen.

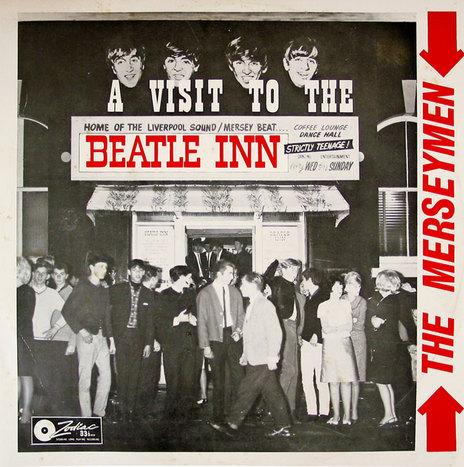

Taite and his parents immigrated to New Zealand from Liverpool in the 1960s. He played drums as a young beat before the move and rose to prominence in NZ initially as Jett Rink, the drummer for The Merseymen, which included guitarist Bob Paris among its members. The majority of the band hailed originally from England, which probably helped them to secure a residency at Phil Warren’s short-lived Beatle Inn club in Auckland. After releasing an album (A Night At The Beatle Inn) and three singles on the Zodiac label in 1964, they switched to Allied International in 1965, releasing a further two singles before breaking up.

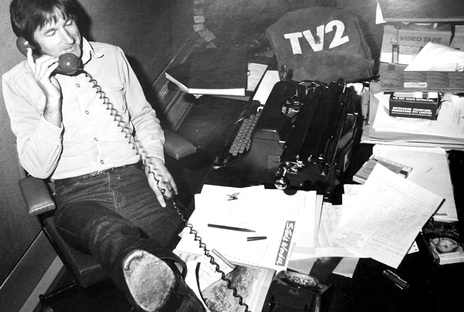

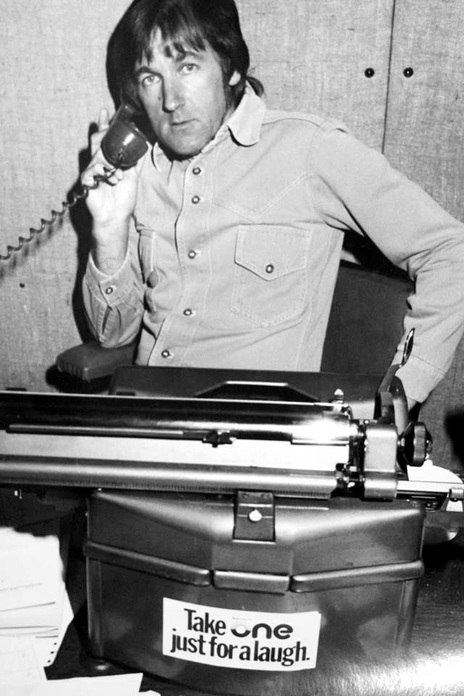

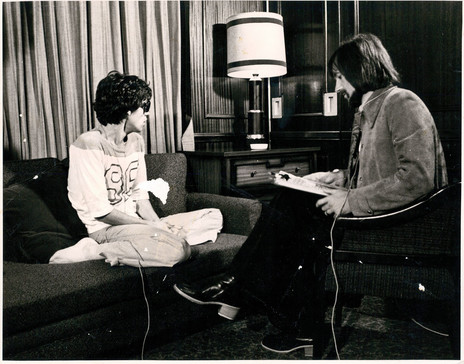

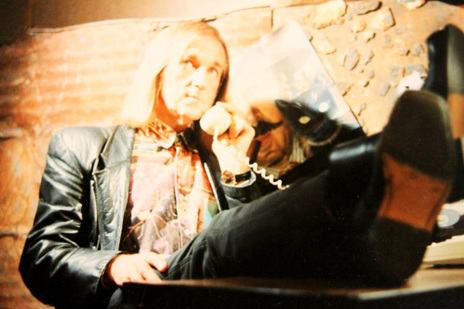

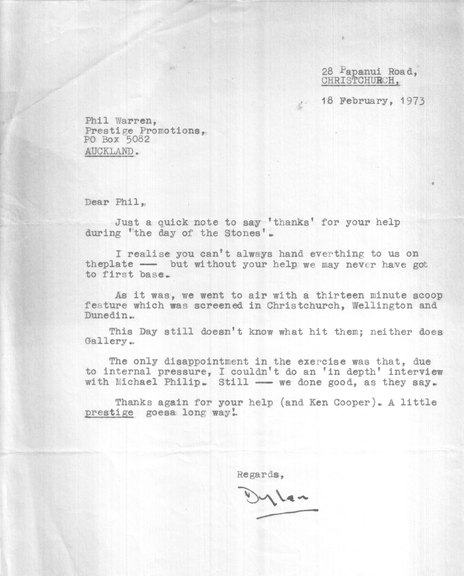

Taite remained a music fan and a radio career at the then NZBC seemed ideal. No doubt that would have served his passion for music well, but he moved to Christchurch and started a job in TV. Using his music industry contacts, Taite scored some scoops with visiting bands. His greatest get during this time was an exclusive with The Rolling Stones. That didn’t so much launch his career as fling it into a wormhole to seed life in the universe.

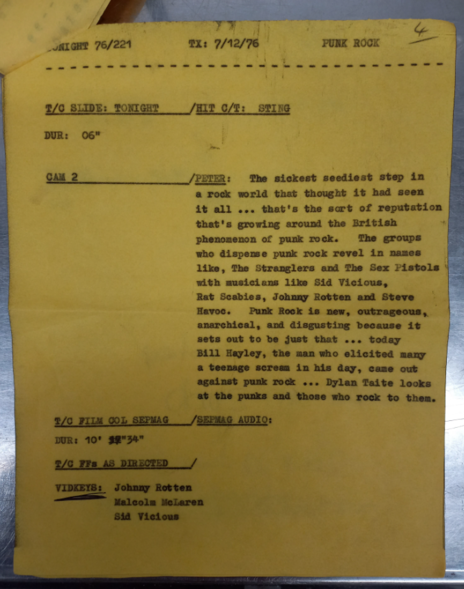

Finally, little old provincial New Zealand had an insider’s line to the world of music out past the Chathams. At least that’s how Taite’s news stories felt on the TV. He interviewed all the greats. During a stint in London in 1976 he hung out with Malcolm McLaren, who was busy creating The Sex Pistols. Taite filmed the infamous 100 Club Special gig and it’s that footage you see in just about every documentary about punk or the Pistols. Taite also had the bright idea of interviewing Rotten et al outside Buckingham Palace. The idea didn’t click with McLaren until he watched the band inevitably act up and the cops were called in. McLaren was taking notes and pinched the idea the following year for a stunt where he had the Pistols sign their A&M record contract in front of the press and Her Majesty’s official London residence.

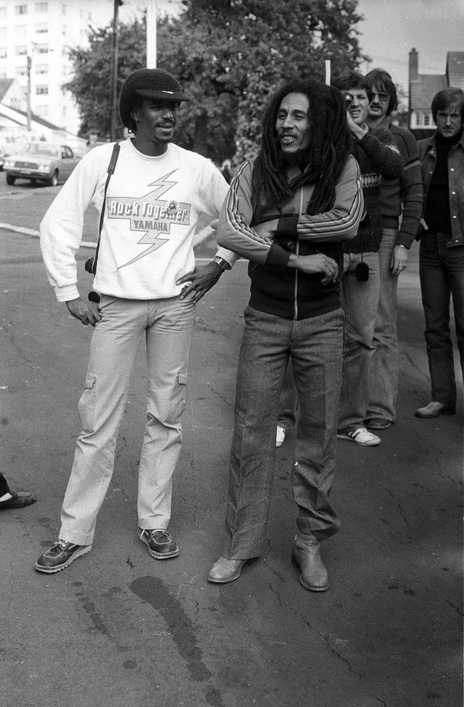

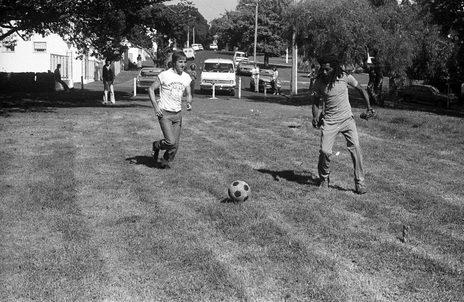

Taite’s ability to position himself like a laser-guided arcade claw and pluck out stories when everyone else had run out of coins served him well. Perhaps his most impressive scoop was his 1979 interview with Bob Marley ahead of his concert at Western Springs. After the Lion declined to talk to any reporters at the White Heron Hotel press call, Taite stayed while the rest of the pack dispersed empty handed. He knew Marley and his entourage were soccer mad, Taite himself was an Everton fan, so he grabbed his boots and waited.

Perhaps his most impressive scoop was his 1979 interview with Bob Marley.

His chance came when the musicians assembled in a nearby park to kick a ball around. They needed extra players to make up a team and a wiry English bloke appeared at just the right time. After a few back and forths Taite had his interview, no doubt aided by his impressive knowledge of soccer.

The footage Taite got is one of the few times Marley was speaking clearly enough for non-Jamaican ears. It appears in most documentaries about the singer, as does Taite’s historically important footage of the concert and the Wailers kicking around in that Parnell park. Contrary to popular belief, Taite didn’t own the footage; it was shot for TVNZ and remains valuable property of the state broadcaster.

In terms of apprehending stories, Taite was a hard-nosed, traditional journo. He’d rise to the challenge of working around other channel’s exclusives. Publicists would feed him misleading flight information, but he’d somehow dodge that and press-gang musicians at the airport or drag them into hotel bars. As Murray Cammick wrote in a Rip It Up memorial for the reporter: “Sinking a meticulously planned Holmes show exclusive was all in a day’s work for Dylan.”

Cameron Bennett, a fellow TV journo, tells of a visit by Alanis Morissette. When the singer-songwriter arrived at the airport she belted past Bennett, Taite and a small girl with a guitar with barely a hint of an acknowledging glance. Turns out the girl had travelled up from Nelson especially to meet the Canadian waif. Taite set up a meeting between the girl and her idol during her visit. The young Nelsonite was Anika Moa.

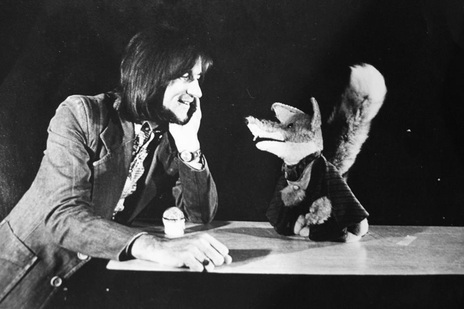

In perhaps the most important way, however, Taite was unlike his colleagues. He was constantly striving for the New. The TV audience was introduced to artists they’d probably never heard before: The White Stripes when they were still a pub band, John Peel, Darcy Clay, The Datsuns, the aforementioned Marley, and this was all on weekdays at 6pm. In a similar vein, his stories were like nothing else during the news hour or half hour. They always jumped out at the viewer because he’d always be trying something new: on the piss camera angles, lens filters, point of view shots – and at his most inventive, the chroma keyed Taite running on a spinning record in close up.

He was always good at presenting current controversies in the local music scene to a primarily clueless audience. There’s a very good early story about the possibility of introducing a New Zealand music quota for commercial radio stations. The programme directors interviewed were uniformly apologetic, but equally strident that their audience wouldn’t accept local music in their lug holes. “The quality of New Zealand music wouldn’t stand a twenty percent quota,” says one sweaty PD. A pissed off Dave Dobbyn (looking like he’s just stepped off the set of Buckaroo Banzai) reckons, “It’s time those people were put in their place.”

Most impressively, however, he could turn a phrase like no one else: “George Thorogood and the Destroyers play straight ahead blues rock. It cuts heating bills in half and sweat drips off walls.” A line like that combines the natural talents of the poet and the efficiency of the time-pressured newsman; somehow it conveys everything you need to know about the music in question with the least mucking around and yet it’s still playful enough to engage the audience.

The taite award seeks to reward originality and creativity regardless of sales

Adding to his gifts, Taite possessed a dry amusement when in the presence of haughty subjects. In his story on the news that the Concert radio channel was finally going to be broadcast in FM in Auckland, the voice reads: “It’s a move that’s given the kiss of life to Auckland’s classical music lovers … “ and as the camera pans onto a snooty white haired interview subject he continues, “ ... many of whom nearly died waiting.” A more perfect marriage of image, voice and tone has never quite been achieved.

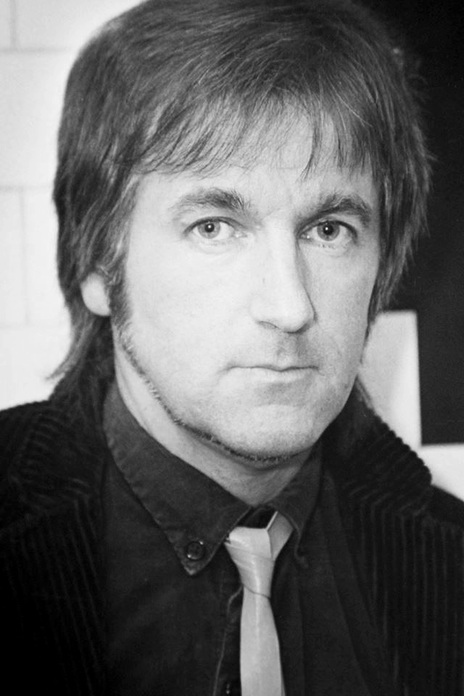

A prestigious music award that seeks to reward originality and creativity regardless of sales now bears his name. The footage he left of some of the 20th Century’s most important musicians continues to serve the planet's ailing memory. Each year since he died in 2003 TV seems to get a little emptier.

A couple of years ago I concluded a similar piece by saying that all you really needed to know about Dylan Taite was that never once while working in TV did he cut his hair. While I think in some way that’s true, I now prefer much more what his son John said in a late night email to me a few days ago.

“He loved to confuse and surprise people. He would intrigue you and then show you the world from a more interesting perspective. Isn’t that what all great artists do?”

--

Read: Dylan Taite, nice to see ya