The two were introduced to each other by Delaney Davidson in early 2006, but their earlier musical journeys explain much about the ongoing story of the band.

McGrath grew up in Christchurch, living with his mum in a series of state houses. By the time he was in his teens, they were living in the city’s northwest, and he went to Burnside High. Even before he finished school, he was a big fellow, a fearsome opponent on the league field. As he began to consider what he might do after school, playing rugby league professionally was one of the options. A guy from his neighbourhood had played in France and England, and it seemed like it might be a fun career.

But before he could don the jersey, McGrath joined metal band Human. He played bass, and though his stint only involved one show and lasted just two weeks, he knew that music was what he wanted to do.

Moving from metal to punk, McGrath became the frontman for a band formed at Burnside called The Bains. With a bit of a Ramones homage, each of the members took Bain as a surname – including a member called David. They were young, and they were punks, but it didn’t always go down well, especially when they played in Dunedin, where the trauma of the Bain family murders was only a few years old.

McGrath was the singer in the Bains, where his league-playing frame and abrasive lyrics helped build a small but loyal following in the punk scene. The band met Nothing At All! at a Christchurch show, and played with them, picking up some tips on how to tour, which McGrath would later deploy.

Following the break-up of the Bains, McGrath played in a couple of other bands, including Sun Tzu, and the Civilians. It was in the latter that he learnt that presentation and image could be just as important as the music being played. However, after the Civilians ended, and following the break-up of his next band, Red Brick Brave, McGrath had had enough of music.

He picked up an old acoustic guitar and found he couldn’t put it down.

A few years later, he picked up an old acoustic guitar and found he couldn’t put it down. He started teaching himself a few songs, and even busked a little. Again feeling like there was something for him in music, he formed a group called The Sweethearts, which also included William Daymond, later of the Pick-Ups. The Sweethearts played around Christchurch, frequently at the old Mainstreet Cafe on Colombo Street.

Buoyed by this passion for playing, McGrath decided to try and make a go of it, heading first to Australia, then to the United States, to try and make a living from music. Starting in Philadelphia, he found he could make a bit of money from busking. He then went to Nashville, to try and crack into the city at the centre of country music.

The going was tough. There were plenty of people chasing the same dream, competing for the same busking dollar and songwriting contract. When he returned to New Zealand from the US, he thought it would only be a brief visit before returning to try again; instead, he ended up buying a house in Lyttelton and making his base there.

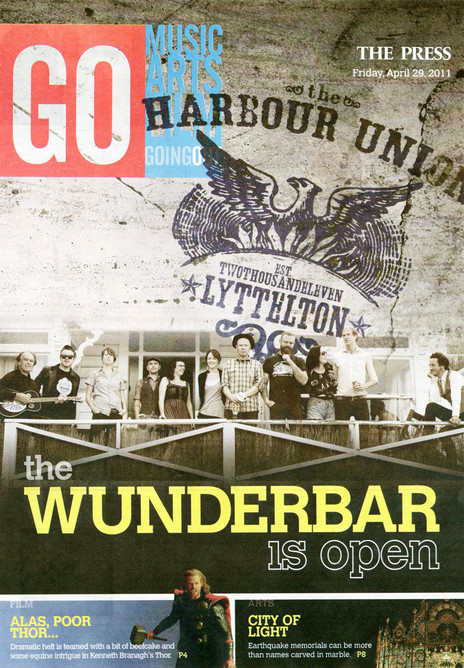

McGrath was living in Lyttelton, playing Wednesday nights at the Wunderbar, sometimes solo, sometimes with his mates, while working by day as a caretaker at the Phillipstown School. Friends told him there was someone else in the town who shared his musical tastes – a woman with a banjo.

Though they hadn’t met, her name kept coming up. “Everyone was talking about this girl Jess who’d just arrived in Lyttelton, who’d been in America and that her and I would get on really good ’cause she loved country music and played the banjo.”

Then one day, a knock at the door. It was Delaney Davidson. He said, “You need to meet my friend Jess, she’s like you.” He brokered a meeting between the two, who met on a Wednesday at the Wunderbar. Adam, meet Jess, Jess, Adam. A couple of hours later, they were playing together on stage.

For almost a decade, Jess Shanks had been back and forth between New Zealand and the Pacific Northwest. Spending her time mainly in Portland, Oregon, and Northern California, she fell in love with the countryside. She was working with her hands, on farms that had many similarities to back home. She wasn’t playing music at the time, but was around the scenes where music was being played.

On one of these trips, she went to the Hardly Strictly Bluegrass Festival in San Francisco’s Golden Gate Park. As Shanks recalls, “I stumbled on Gillian Welch playing the banjo and it just blew my mind.”

When she got back to Portland, Shanks resolved to find one of the instruments. In her time in the US, she wasn’t forming and playing in bands as such, mainly joining in with groups at house parties – “pretty much just friends, sitting round campfires.”

Portland at the time was a hotbed of indie music. Building on the DIY energy that had exploded from Seattle in the late 80s and early 90s, the city had a strong punk and hardcore scene. By the end of the 90s and the early 2000s, this had led to indie rock groups like the Dandy Warhols and Modest Mouse. By the mid–2000s, it was the home of groups such as the Shins and the Decemberists, who combined the indie and DIY ethos of the 90s hardcore scene with a much less threatening style of music.

After playing a few shows, Shanks and McGrath discovered they had a great rapport.

As well as groups with strong country influences, such as Wilco, this period saw a “neo–folk” renaissance, with artists from Northern California like Joanna Newsom and Devendra Banhart, as well as the Fleet Foxes from Seattle. When Shanks returned to Lyttelton, folk and country music were very much living genres, rather than the nostalgia trip that many might think.

After playing a few shows, Shanks and McGrath discovered they had a great rapport. McGrath remembers that “we were both kind of the same, heading towards 30, had travelled, done all this weird shit, had these other lives, and this is the time that life seems to change.”

They then resolved to both quit their jobs, and make the band their sole focus. “I was working as a school caretaker and also had my own little garden fix–it business … she’d just had her heart broken, didn’t really know what she was doing. Let’s not do anything else, let’s just quit everything, we’ll only play music.”

Shanks was also on board with the plan. “Only after two weeks that we said let’s do this … but we didn’t know what doing this meant, because there was no landscape for what we were doing. I barely knew how to play the banjo when we met, but I wanted to play music with him, so I told him I could.”

To make a living, they had to play. This meant The Eastern would play any show they could find – sometimes for a guarantee, sometimes for tips. “First it was for tips, then it was $50 and tips for an hour, then it was two hours, then it was four hours, then it was two or three nights, four-hour sets, and just that playing all the time, it’s a really old fashioned way to do it. Doing those bar shows, we would just play whatever songs we knew, sometimes three or four times in a row ’cause that was all we knew. We would just do whatever we could to play. Play anything, everything, ’cause we had to make money to live.”

They would play four, five, six nights a week: no mean feat in a city the size of Christchurch. There were times when they would play multiple occasions on the same day – starting in Lyttelton at the Farmer’s Market, heading into Christchurch to busk in the afternoon, before a show at a pub in the evenings.

They became professional musicians by making music their vocation; there was no better place to work a room than a room. “She wasn’t a very good banjo player, I wasn’t a very good guitar player, but in that process of just doing it, we became better and it became something good.” It was the making of the band.

As Jess says, “we really had to figure out how to put on a show that people would respond to.” While they were starting to write and perform their own songs, they also weren’t afraid to give the crowd what they wanted, peppering their sets with requests and old favourites.

With McGrath on guitar and lead vocals, and Shanks on banjo, this was the core of the Eastern – but there were many other important players who drifted in and out of the band. The Eastern was a vehicle, and in keeping with the group’s practical, industrial vibe, that vehicle was a train.

Adam explains: “the reason we do it, the reason we started it, was to escape the constrictions of the every day and to have adventures, so it was this little train that you could get on or get off, and people have got on, and then they’ve got off, and then they get on again, so we’ve had heaps of people through the band, but that’s cool, it’s always been that way.”

Some members had short trips, others longer ones; some people have got on and have never got off. Alongside McGrath and Shanks, the next constant has been Jono Hopley, on double bass. The low end is an important foundation for any band, and this was perhaps even more key in The Eastern, where there wasn’t always a dedicated drummer. Hopley has a vital cog in the group since he joined, keeping the wheels turning.

On an early tour, they were playing a show with the Ragamuffin Children. They would often ask Anita Clark from that duo to join them on fiddle, which then led to her joining the band proper. Her role on fiddle was such a key part of the Eastern’s sound that when she left the band, a replacement had to be found.

Initially, this was Flora Knight, though the band itself jokes that they’ve had “nearly as many fiddle players as Spinal Tap had drummers”. Clark has gone on to play in groups including Devilish Mary and the Holy Rollers, and Dog Power, as well as making more ethereal, experimental music under the moniker Motte.

Though the Eastern were playing shows around town, and heading off on tours round the country, they were still continuing to busk as well. One occasion was particularly fortuitous to the band – and possibly to the wider story of New Zealand music. McGrath had a regular spot in the city where he would open up his lungs and his guitar case.

“One day I went down there and Hannah was in the spot where I was busking. She was singing ‘Angel from Montgomery’ by John Prine, which I sung too. She was maybe 17 at the time and she was incredible, so I said you should come sing with us. We sung together that day, and then I said you should come sing with the band.”

Hannah Harding – later known as Aldous – then went overseas and the band didn’t see her for almost a year.

The young woman in question, Hannah Harding – later known as Aldous – then went overseas and the band didn’t see her for almost a year. Then, when the Eastern were holding down one of their residencies at His Lordship’s Lane, they ran into her again, and asked her to join the band. This chance encounter led her to the Eastern, and through the Eastern to many of the other important connections in the Lyttelton scene, including Ben Edwards, who recorded her debut album at the Sitting Room.

The current line-up of the band features at least two members who have their own solo careers: Reb Fountain and Adam Hattaway. It shows that they weren’t just a band who happened to feature some talented musicians for a time, but a unit that was able to work with and nurture talent. But most importantly, they’re just people who like to play music together, as Shanks says, “everyone who’s been in the Eastern, they’re like family. Those friendships are so thick.”

Building on the DIY ethos that Shanks had picked up in Portland, the band set about recording and releasing their first EP, 2007’s Get Right. The simple but effective use of black on cardboard tied the visual aesthetic to the band’s musical one. McGrath oversaw the design, teaching himself Photoshop so that he could also handle the endless production of tour posters.

While the first EP was a bedroom production, by the time of the follow-up, 2008’s Crow River, The Eastern had teamed up with the Sitting Room – a partnership that would prove fruitful for both parties. Their self-titled debut album was released in March of 2009, adding some of the songs from the first two EPs in with some written for the album. The cover was the first to acknowledge Lyttelton’s place in the band, with a woodcut by artist Scott Jackson depicting the ships in the harbour, backgrounded by the Port Hills.

This was an incredibly fertile period for the band, with their third EP, Oh Mystery, coming just six months later in October 2009, and the second album, Arrows, in March 2010.

The earthquakes were devastating for Christchurch and Lyttelton, and there is no band that better encapsulates the struggles, challenges, and community that was born in those times more than the Eastern do. The band members weren’t actually in Christchurch when it happened. They were on tour – of course. It was late summer, and they were waiting to get their car onto the Interisland ferry for the journey south. Soon they were back in town, trying, like everyone else, to find their families and loved ones, to help when needed.

It was a disaster, but also brought a sort of clarity to the band, as Shanks sees it. “It was really sobering, but it gave us a sense of purpose.”

McGrath came off stage to find marlon Williams in tears, as many people were after the quakes.

Just a week or so later, the band were booked to play a show at the Hokonui Moonshine Festival, alongside Tami Neilson and Marlon Williams. After one of the sets, McGrath came off stage to find Williams in tears, as many people were after the quakes.

“I remember coming off stage and Marlon was backstage and he was just crying ’cause of all the shit he’d been through and I gave him a hug and I said look man we’re just gonna sing man. It made us stronger to be together. What was good about that was the solidarity of being together, that was the most important thing.”

McGrath and Williams resolved to find something good in this disaster, and the idea of the Harbour Union was born. Back in Lyttelton, the idea came together. Even though the quakes had taken out almost all of the regular venues that these bands could play at, and thus their main source of income, the Harbour Union wasn’t about fundraising for the artists, but for the communities. It was a way for people who might not always be that practical to contribute something to the recovery. Alongside the Eastern were other Lyttelton stalwarts: Delaney Davidson, Lindon Puffin, Al Park, The Unfaithful Ways, Tiny Lies and Runaround Sue.

As well as releasing a CD to raise spirits and raise some funds, the band were able to give back in other ways. Their music was always about community, about bringing together – and so that’s what they did. As Shanks saw it, it was their way of helping out. “I guess we didn’t really know what else to do that was practical. We’re just musicians, but maybe we can just take a load off for people.”

They began by playing shows at parks and BBQs where people were gathering together in the wake of the quakes. Then they were asked to play at people’s shows, and the next thing you know, they were on tour again – a tour of munted backyards. McGrath remembers “we did so many gigs, I couldn’t even count them. One weekend we did 13 gigs.”

At the end of 2011, the band lodged their live performance reviews with Apra, as any band that regularly tours would do. A couple of weeks later they got a message from Apra querying whether they had really played so many shows. They weren’t used to a band playing so many shows – and at so many different venues. The music editor for the Press, Vicki Anderson, wrote a letter in support of them, confirming that they had indeed played that many shows. No one ever said being the hardest working band in the country would be easy.

As anyone who lived through the quakes will tell you, time was unquantifiable. Things took far too long to happen – water, roads, repairs – while looking back at the time, it just sped by. When 2012 rolled around, it had been two years since the last Eastern record. A long time between drinks when there had previously been one, sometimes two releases each year. So much had happened, and there were stories to tell. This period culminated with the recording and release of their most successful record, Hope and Wire (2012).

For the recording of the record, the band were fortunate to be lent a house in Christchurch’s Red Zone: the area to the east of the CBD that was most badly affected by the quakes. The original owner had moved out, and so had most of the neighbours. Ben Edwards moved his Sitting Room studio in, and the band had full use of the house for about three months. One room might be used for practising and tuning up, while vocals were being recorded in another, and lyrics were being written in the kitchen. The album also reflected a change in the songwriting direction.

McGrath: “It changed what I wanted to write songs about. Before I was quite happy to write a song about drinking and standing on the tables, having a big yee-hah, and I still believe in that deeply, but then I started to see that music can have a different role in people’s lives. I want to make music that has some kind of component of weight to it, and that’s cheesy and I get it and I understand and it’s not for everyone, cos it’s not very cool, but it gives me a comfort, and allows me a way to try and figure shit out.”

‘hope And wire’ provided a name for Gaylene Preston’s mini-series about the quakes, which featured the band.

Released by Rough Peel Records, it went to No.2 on the New Zealand chart, without a heavy promotional push or a music video. It was on the strength of the music, and the reputation that The Eastern had built by their hard work and touring.

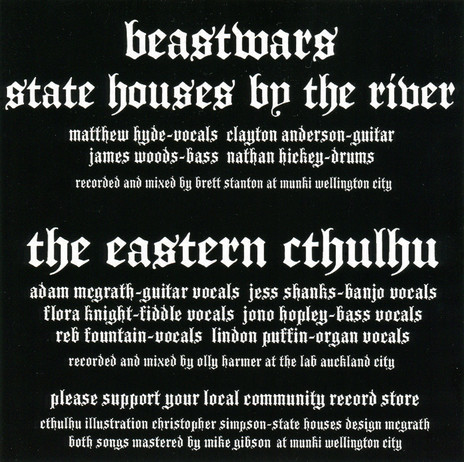

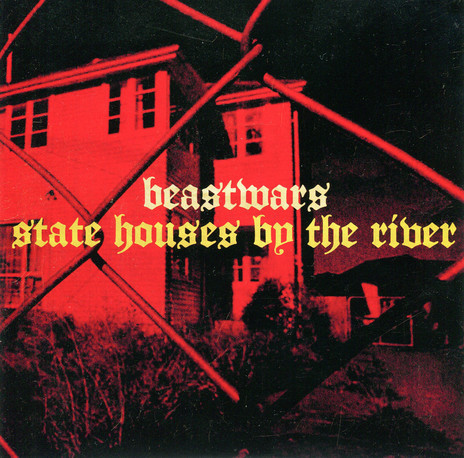

The name of the album was then used by Gaylene Preston for her mini-series about the quakes, Hope and Wire, which featured the band. The Eastern were acknowledged at the 2012 Apra Silver Scroll, with ‘State Houses By The River’ being nominated for the song of the year. It was covered on the night by metal band Beastwars, an unlikely pairing, but one that would have put a smile on the face of McGrath, who had started his musical journey 20 years previously playing bass in a metal band.

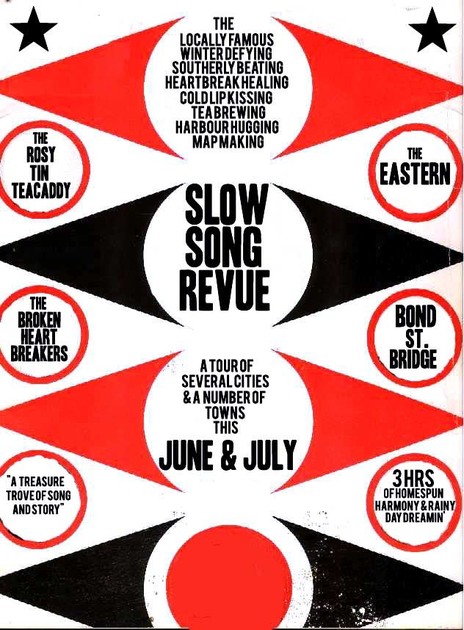

For a band that was happy to gig to a couple of people in a pub on a Monday night, they’ve gone on to play with an impressive list of names. One of the most enduring links is between The Eastern and The Warratahs. The resurgence of folk and country music saw the two groups develop a respect and an understanding together.

The Eastern have supported an eclectic list of acts, including Paul Kelly, Steve Earle, Old Crow Medicine Show, Jimmy Barnes and, in 2009, Fleetwood Mac. The latter demonstrates just what can happen if you give your all every show, no matter how small it seems. As Jess recalls it “came out of playing at a shitty sports bar. We’d go to New Plymouth. There was never really a suitable place to play. We were playing at this Irish pub, in front of a big screen, maybe three people. One of those three people just kept an eye on us … and he was the guy who brought Fleetwood Mac over. Every show counts.”

Touring with Steve Earle meant a lot to Adam, but maybe more to his mum: “When I was a kid I sung ‘Copperhead Road’ at the Papanui Working Mens Club ’cause my mum made me. She loved Steve Earle. [Now] I’ve been on tour with him a few times, it made me feel I was worth something.”

Perhaps unsurprisingly, McGrath’s favourite show to open for was the working class man himself, Jimmy Barnes. “The best person we’ve ever opened for was Jimmy Barnes, hands down. You couldn’t buy the kindness in the heart of that man. Jimmy Barnes makes you believe, there was a real trueness there that I really respected.”

While they’ve played with some of the biggest bands in the world, it has never gone to their heads. “I’ll always be in the band that got to open for Fleetwood Mac, but had just as great shows playing for two people, probably more meaningful.”

Back in the studio, the band’s follow-up to Hope and Wire was perhaps their strongest mission statement, The Territory (2014). Recorded again with Ben Edwards at the Sitting Room, it was a record that explored their own place.

As McGrath wrote: “The territory being here, these isles on which I write this, this long southern island below the northern one, this eastern coast, this flat and bruised city, this one-bed cinder block refuge I sit in, this old desk my feet fit under, this machine that gets the words down and this body, heart and mind that has to figure out the songs and listen to my co-pilot Jess Shanks figure out her ones also. These songs put their fists up and wanna get down in the dirt with place. We wanna arm wrestle the here and now. We want to explore the things we've seen and done and make songs out of 'em.”

The band celebrated its first decade with a massive gig in the carpark at the Tannery.

Following the release of the album, and the inevitable tour, the band decided to slow down. They could see that the wheels were going to fall off if they didn’t – almost 10 years of hard work and long drives in a shitty van will do that. As Jess saw it, “we pushed ourselves really fucking hard, we drove ourselves really hard, we worked and worked and toured and toured, we had pushed ourselves, the wheels were starting to come off. It was a really hard decision to make.”

The band celebrated a decade of being together with a massive gig in the carpark at the Tannery at the end of 2016. A thousand people, special guests, broken hearts, hoarse voices.

The Eastern haven’t broken up, they just aren’t playing as much as they used to. Even when they are holding back, they still play more shows a year that most bands. McGrath continues to tour solo, with a recent Arts on Tour jaunt taking in both islands, then followed up by a trip across the ditch.

Shanks has been running Blue Smoke, the music venue at the Tannery, for a couple of years now. It provides her with some of the security and stability that a band never could – and also means she’s less able to put it all to one side and head out on the road.

The Eastern might be New Zealand’s most progressive band. They don’t have to wear shirts that say “Listen To Women” – they just ask you to listen to the women. As Shanks puts it, “It wasn’t a gender thing at all – we were just the best men for the job”.

They’ve played for good causes, for unions and for striking workers, for charities and for fundraisers. They’ve gone out and played for people in their communities, their gardens, their schools, their houses. There is an immense honesty in The Eastern, not just in the style of music that they play, but in the way that they treat the band as a vocation, not a vacation. They take it very seriously, and they work hard at it, and reap the rewards of what they put in.