AudioCulture

The noisy library of New Zealand music

Te pātaka korihi o ngā puoro o Aotearoa

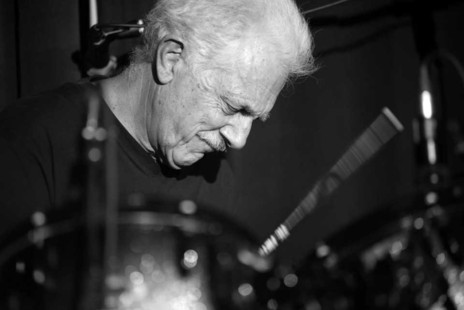

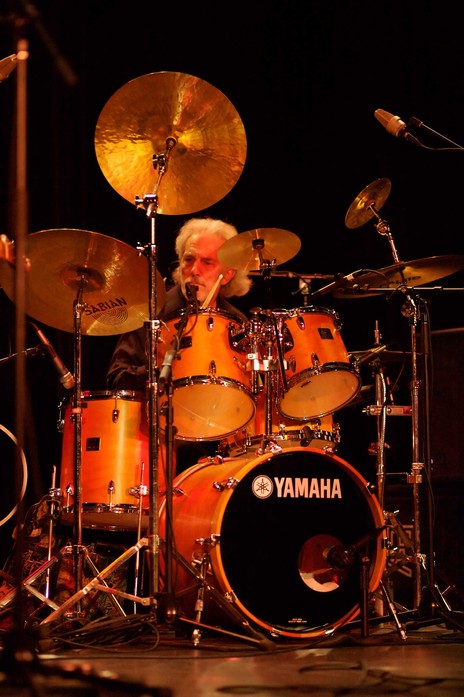

Raice McLeod

McLeod spent decades on the road in Australia, the UK and the US with show, club and jazz bands, but his highlight was five years in the drum seat with the Eva Cassidy Band in Washington DC, until she died in 1996.

Cassidy remained unknown outside the Washington area until two years after her death when the world got to hear of her enormous vocal talent and her album sales exceeded 10 million copies worldwide.

Raice McLeod’s first paid gigs were with keyboardist Bob Smith in a Top 40 band playing Saturday nights at the Travelodge Hotel in Hastings, Hawkes Bay, in January 1968. In March he got a call from Malcolm Hayman to audition for Wellington brassy rockers The Quincy Conserve.

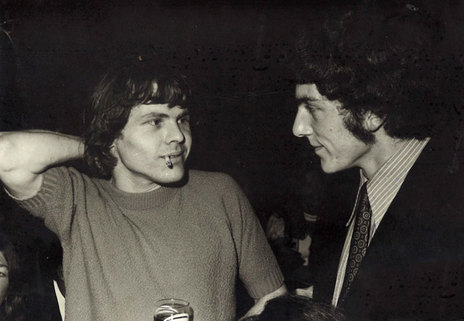

The Quincys had only recently begun their residency at the Downtown Club in late February 1968 when McLeod was called on to replace former Quin Tiki drummer Earl Anderson, who had been laid up with hepatitis.

McLeod stayed in the drum seat until November 1969 when he got a phone call from Auckland bass player John Coker to join Ricky May’s backing band in Surfers Paradise. Bruno Lawrence, who was playing with fellow New Zealanders in Electric Heap in Sydney, returned to New Zealand to take up the vacancy with Quincy Conserve.

Australia’s most wanted

McLeod played alongside Coker with Jamie Rigg on keys and Doc Parker on guitar, backing Ricky May’s shows for about six months, then went on the road with Ian Saxon and the Sound. Saxon, a well-known 1960s Auckland cabaret compere, guitarist and singer, had released the 1965 single ‘I'm Getting Better’. Also in the band was Colleen Hewitt (later an Australian 70s pop queen) on vocals, Ted White on alto sax and Graeme Trottman on sax and second drum kit. “We used to do a duo drum solo as part of the show,” says McLeod.

Saxon later become known as Australia’s most wanted man after escaping from Sydney’s Long Bay Jail in a laundry van in 1993 while awaiting trial for laundering an alleged $96 million in drug profits. During his time working with rock promoters as tour manager in the 1980s he helped bring to New Zealand artists including Elton John, Kylie Minogue, The Police, Madness, Dionne Warwick, Duran Duran, Stevie Nicks, ZZ Top and Bon Jovi.

With McLeod in one of two drum seats, Ian Saxon and The Sound played Sydney, Melbourne, Adelaide and places between. Things didn’t always go to plan – like the time a north Adelaide club failed to pay them.

“We had to do a moonlight from the motel climbing down a fire escape at 3am then pushed the van a block or so before starting it up and heading off for another booking in Sydney.”

The band scored a long residency at the Coogee Bay Hotel in Sydney where they backed many touring singers and acts. At the Coogee gig McLeod met popular Australian rock and roll bands The Delltones and the Going Thing, who proved to be valuable contacts.

Jazzing things up

McLeod joined the Delltones in mid-1971. “It was a great gig, I got a retainer every week whether they played or not, so I could do whatever I wanted as long as they had first call on my time.”

During that period he hung out at all the Sydney jazz clubs, sitting in with the bands whenever he got the opportunity as a hands on chance to get skilled in the genre.

After six months with The Delltones, he was invited to join Greater Union for a tour of the UK. Greater Union had morphed from studio pop group The Going Thing, which originally formed as a promotional vehicle for the Ford Motor Company. The other addition to the band in November 1971 was Stan White, the New Zealand keyboardist formerly with Chapta and a founding member of top Australian band Pirana.

Greater Union had a contract in London with Carlin Music (an EMI publishing subsidiary) but the trip was put on hold for several weeks. Not one to waste time, McLeod toured every high school in Tasmania and played clubs with trad jazz guitarist and banjo player Ray Price.

In the UK, Greater Union toured with Olivia Newton-John and Cliff Richard, played countless clubs, pubs and bars all over the British Isles and recorded several singles, including ‘Someone Like You’ in 1973, which reached No.3 on the German charts.

McLeod left the band to record with Jackson Heights, featuring ex-Nice bass player Lee Jackson, recording one track, ‘Chips and Chicken’, for their album before Greater Union got an offer to reform and go to the USA.

They played eight weeks in Puerto Rico from late November 1973 then went on to New Jersey, Philadelphia, Trenton and Washington DC, by which time McLeod was looking for an out.

Ever touring showbands

“I left to join The Ken Hamilton Show, a Vegas-style show band, and Greater Union staggered on for a few months then shattered from internal personnel issues.”

He remained with the show band for eight years, playing across the US, Canada, the Caribbean and Hawaii and married its female co-star. When the band and his relationship split in 1981 he was back on the road with another show band covering the length and breadth of the USA “many times over”.

For a while he was in a Top 40 rock band called Itchy Fingers, playing six nights a week in Washington DC and Baltimore. McLeod returned to New Zealand in 1986 on learning his father was critically ill.

McLeod remained in his home country for two years, playing “some excellent music with a fine group of Napier musicians: David Boston on guitar, Peter Thwaites on bass and Terry Wilde on sax.

In September 1988 he flew back to Washington to join another Top 40 band but the times were changing, along with the ability to play clubs six nights a week. He worked with black tie bands playing weddings, bar mitzvahs and corporate and political parties. While he says the money was good, it wasn’t musically satisfying.

Teaming up with Eva

Eva Cassidy’s career began in 1986, when she met bassist and recording engineer Chris Biondo, who got her work as a backup singer for various acts. In 1990, Biondo and Cassidy pulled together the first band to for her frequent gigs in the Washington area. Finding the right drummer was problematic.

In late 1990 Raice McLeod received a call from Chris Biondo asking him to audition. “Their drummer had left, it was a work in progress, there were no firm gigs … but he had his own studio, the players were good … and this singer, he assured me, was the best singer I would ever hear in my life.”

Sceptical but curious, McLeod turned up at the studio and was impressed with the recording console, musical equipment and the acoustics. He was introduced to guitarist Keith Grimes and “a young blond woman sitting it the corner … quietly doodling on an acoustic guitar as she observed the interactions.”

McLeod says he immediately noticed three things. “She was completed unadorned, wearing what appeared to be agricultural work clothes, genuinely pretty … and obviously not immediately outgoing with strangers.”

He stepped into the seat of “a dilapidated old Pearl Export set. I adjusted things … and announced I was ready to do a drum check. What I heard was a revelation. That tired old set sounded just fine.”

Biondo told him the band played an eclectic mix of old blues ballads, R&B, some swing and a few examples of old pop. They didn’t play copycat, they had their own interpretations and arrangements of all the cover songs. They were sensitive musicians and, says McLeod, there was no evidence of rampant egos.

“Having been exposed to many bands that require the drummer to spend every bar treating the snare as if it were a recalcitrant nail and the stick a four-pound hammer, it was refreshing to be asked to play brushes, to stroke the instrument when appropriate, to filter in with soft, smooth sounds … this was both satisfying and pleasing to my ear.”

Effortless vocal ease

Like most people who heard Eva for the first time, he was struck by the effortless ease with which she sang. “Though merely coasting through a few songs for an audition, she did not miss a thing. Every note was perfectly pitched, every phrase relaxed and properly placed, and the pure power and quality of her tone was stunning.”

The band had agreed among themselves to hire McLeod but for some reason they took their time telling him. That only became apparent when he got an urgent call to turn up at a studio.

Cassidy was waiting to record an album of duets with jazz and blues vocalist Chuck Brown and his drummer had failed to show.

Cassidy was waiting to record an album of duets with jazz and blues vocalist Chuck Brown and his drummer had failed to show. On arrival McLeod noted pianist Lenny Williams, “an exotic black gentleman with a gold tooth smile” and found himself being introduced by Biondo as “the new drummer”.

Everyone threw song ideas around and within half hour, McLeod’s suggestion of Peggy Lee’s 'Fever' had been accepted and an arrangement agreed on. By the end of the first session, McLeod was asked to stay on and complete the project.

The result was The Other Side, featuring classic songs ‘Fever’, ‘God Bless the Child’ and Cassidy's signature tune ‘Over the Rainbow’.

Completing the album and being asked to join the Eva Cassidy Band was “a red letter day in my musical career with far reaching effects,” says McLeod.

No compromise

The band stayed together to promote the album. There was some interest from record labels but they all wanted Cassidy to decide on a particular style like pop or jazz, something she adamantly refused to do.

McLeod, now officially part of what became known as The Eva Cassidy Band (ECB) began playing regular gigs around the Washington area with Grimes on lead guitar, Chris Biondo on bass, Lenny Williams often on keyboards and Eva on vocals, guitar and piano.

Grimes said it had been hard finding someone for the early gigs, partly because they didn’t pay a lot, but finding McLeod however was a big relief. “Raice was the perfect drummer for Eva, in all the various styles of music. Most of all, he could do different volumes better than any other drummer.”

He says Eva liked the onstage volume to be very low, almost like a jazz group. “I kind of feel we had a better handle on our onstage volume level than any other group in town.”

The band continued playing pubs and bars around Washington DC for $250 or less a night, “competing with the noise of pool games, arguing drunks and jukeboxes,” says McLeod.

In 1993 Eva Cassidy was awarded Washington area music awards for “Female Vocalist Roots/ Traditional R&B” and “Vocalist Jazz/ Traditional” but was still struggling to find the support needed to advance her career.

“We used to take boxes of The Other Side to gigs. If we sold five in a night Eva reacted as if the stock market had skyrocketed. That was Eva. No ego, just the greatest voice I’ve ever heard,” says McLeod.

Way past paying dues

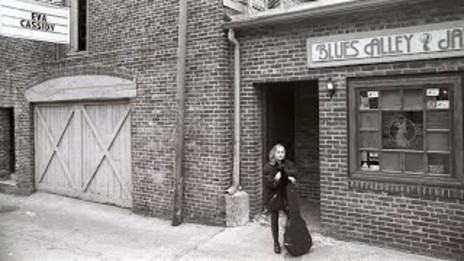

By late 1995, frustrated at the lack of response from record labels, the group agreed to do a live recording as an interim move while Cassidy and Biondo worked on a studio album. It was hoped a range of new material might elicit more interest and hopefully better paying gigs. The band paid $1,000 for a recording engineering to capture them live at Blues Alley, hoping to sell 1,000 copies.

Two 70-minute shows in January 1996 weren’t expected to place any strain on a band used to playing four-hour nights without repeating tunes. The venue had great acoustics but the recording was being done in the middle of winter and the club was badly insulated.

During the warm-up process the players were dressed as warmly as possible, even wearing gloves, until they were due to start playing. The engineer thought he’d got rid of line noise on the first night but it showed up, making the recording useless.

The second night Cassidy was more relaxed but the cold she had contracted didn’t let up. McLeod says she sounded fine and seemed to enjoy herself with the smaller audience and was “resigned to the now-or-never reality of a one-night recording opportunity”.

Cassidy remained unhappy with her vocal performance although, the Washington Post reviewer was clearly impressed. “She could sing anything and make it sound like the only music that mattered.”

During a promotional event for the Live At Blues Alley CD in July 1996, Cassidy noticed an ache in her hips. She thought the stiffness may have resulted from her painting murals but it persisted and within weeks she was diagnosed with melanoma, which had by this time spread throughout her body.

Posthumous stardom

Cassidy's health rapidly deteriorated, and using a walking frame for her final performance in September 1996, she took the stage to sing ‘What a Wonderful World’ before an audience of friends.

She was admitted to Johns Hopkins Hospital and died on 2 November 1996. Her studio album was released as Eva By Heart posthumously in 1997. Her music was little known during her 33 years of her life.

It was two years after her death that British audiences first heard her version of ‘Fields of Gold’ and ‘Over the Rainbow’ played on BBC Radio 2 to an overwhelming response. Then a camcorder recording of ‘Over the Rainbow’ from Blues Alley was shown on Top Of The Pops.

A compilation album called Songbird climbed to the top of the UK charts three years after its initial release, leading to worldwide recognition.

A compilation album called Songbird climbed to the top of the UK charts three years after its initial release, leading to worldwide recognition. Overall her albums have sold over 10 million copies posthumously. Raice McLeod plays on all tracks.

When Eva passed away McLeod was still playing black tie gigs and subbing with different jazz and smooth jazz bands. He was later contacted by former ECB guitarist Keith Grimes who was working with blues and R&B singer Mary Shaver when their drummer left. He remained with the Mary Shaver Band until 2014.

He continued to work with Grimes in Liz Springer and the Built 4 Comfort Band, in a musical partnership that has lasted around 25 years. He still plays on occasion with other Eva Cassidy Band members Lenny and Chris and fills in with other jazz units on call. “Old jack-of-all trades that I am, I can usually cover whatever comes up.”

McLeod has just completed a book on his time with the Eva Cassidy Band and another on his experiences on the road with what he calls “no-name bands”. “You know, the bands that grind out the week-long engagements in Holiday Inns and the like. Always travelling, never famous but often making some great music.”

Some of those stories are from his days in New Zealand and Australia. “The names will be changed to protect the guilty,” he says.

HMV

Visit our sister site

NZ On ScreenMade with funding from

NZ On Air