Rim grew up with his grandmother at Whakarewarewa. “At times my father’s band would come and play at the meeting house in Whakarewarewa – or waka as it was called then. In those early years I can remember him coming to Waka, and I’d fall to sleep under the stage during the dances. Being the son of the man who was the leader of the band, nobody bothered me.”

Tai Paul played alto saxophone as his main instrument plus tenor sax, guitar, accordion, and piano. “He just loved music,” says Rim. “And entertaining people.” In the 1950s and 60s, Rotorua was the entertainment capital of New Zealand, known for its cabaret-style productions. Locals and tourists from around the country went to the Tama to dance, especially on holiday weekends, Easter, and over Christmas and New Year. “They got good music, good entertainment – they had a great time.”

As a teenager at Te Aute College, Paul sang doo-wop with a group called the Teenage Rebels

As a teenager in the mid-1950s, Paul sang doo-wop with a group at Te Aute College called the Teenage Rebels, then began singing rock and roll and ballads with his father’s band. The Pōhutu Boys’ set lists were notable for their variety: They would play set dances like the maxina and the Gay Gordon, big band swing, a Latin bracket, rock and roll, country music, Hawaiian pop, and do musical impressions – changing costumes throughout their shows. Many of these techniques would later be incorporated into a typical Māori showband set.

By the time Paul began performing with the Pōhutu Boys, rock’n’roll had come in “and that was the waka that lead me into it. That, as well as the Platters. Because all the other musicians were, like my father, older people. There was a young lady – a couple of years older than – who was doing women’s songs, but also things like Little Richard’s ‘Long Tall Sally’, ‘Great Balls of Fire’, the Jerry Lee Lewis thing. That style. But I came in with Elvis Presley. There was another singer – Angus Douglas – who was a Māori All Black, and he used to do the Perry Como, Bing Crosby-style of singing. So we had all the different styles of music covered in the singing department.”

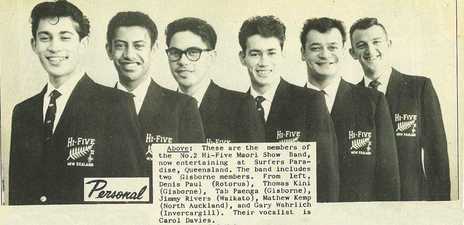

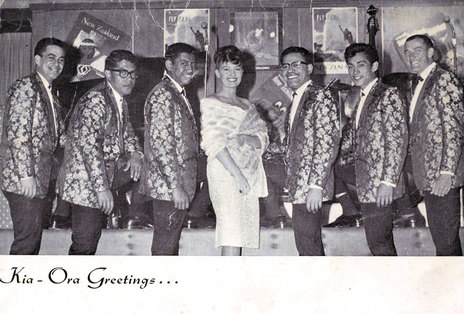

After Te Aute, and a stint at Rotorua Boys High – which is when he started performing with the Pōhutu Boys – Rim decided he needed “to go to the outer world”. He headed to Auckland, then Wellington, where he met people who wanted to fill out a band. It turned out to be the Māori Hi Quins, the second band, after the Māori Hi-Five, to be formed by the High-Five Company.

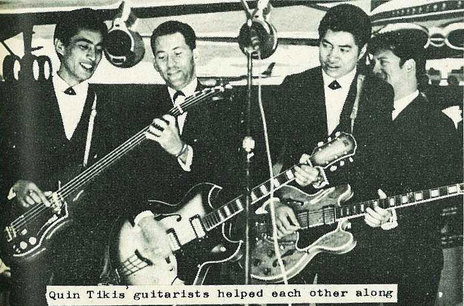

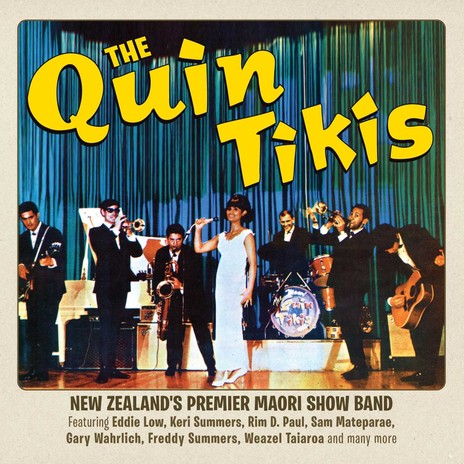

The Māori Hi Quins followed the Hi-Five to Australia. They were especially popular on the Gold Coast, but also toured Britain and Europe. Paul left in 1963, and joined The Quin Tikis.

In 2011, looking back at his time as a member of the pioneering showbands, Paul said, “Let’s face it, we were being groomed to become professional entertainers. In those days you couldn’t go on stage in jeans – you wouldn’t get the gig. We looked like the All Blacks in our black blazers with the silver ferns, but that was part of the job. You had to dress smart, and look available. Learn how to handle yourself.

“The one thing we didn’t learn at the time was how to handle the business side. We got taken for a ride, but somehow that seems to be the norm in this business. But I wouldn’t have traded that life for anything, and I’d like to be able to pass that on to the future. There are a lot of pitfalls along the way.”

Thanks to Sammy Davis Jr taking a shine to The Māori Hi Quins after seeing them at the prestigious Pigalle club in London, he invited them over to appear with him at the Sands in Las Vegas. But Jim Anderson, their manager, didn’t take up the offer, wanting the Maori Hi-Five to be the company’s first act in the entertainment Mecca.

In 1963 Paul recorded the uniquely New Zealand rock and roll song, ‘Poi Poi Twist’

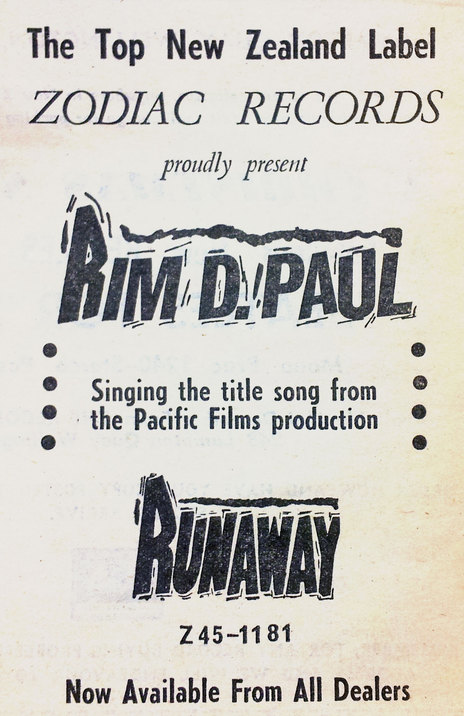

In 1963 Paul recorded a uniquely New Zealand rock and roll song with The Quin Tikis. ‘Poi Poi Twist’ was written by Jay Epae, the brother of Wes Epae in the Māori Hi-Five. Paul added a chorus from the traditional Māori song ‘E Papa’, so that the sweaty, generic rock and roll groove kept returning to the marae harmonies of his youth. It was an idea later borrowed by Herbs and Dalvanius Prime. His other solo singles in the mid-1960s included the title song to the 1964 New Zealand feature film Runaway, written by young Wellington composer Robin Maconie.

Directed by John O’Shea, Runaway opens with a clip of Paul and The Quin Tikis performing in a club. In 1966, Paul and The Quin Tikis were featured in O’Shea’s slapstick musical Don’t Let It Get You, set in Rotorua and also starring Kiri Te Kanawa and Howard Morrison. The Quin Tikis carried on without Paul, performing around the world, and even doing a tour of duty in Vietnam, entertaining the US troops.

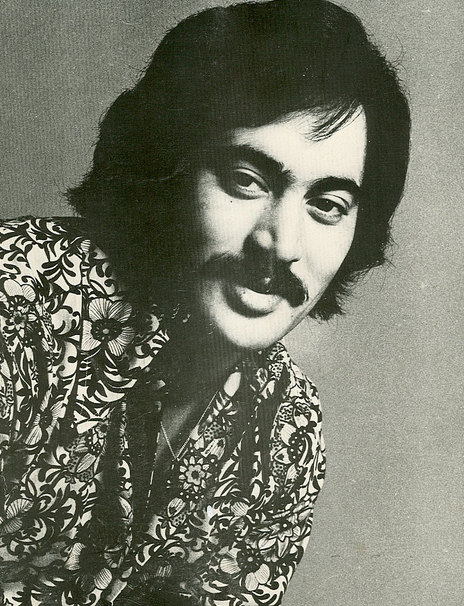

Paul’s rich, baritone voice made him a powerful interpreter of the velvet bow-tied ballads of the 1960s. His biggest influence was Billy Eckstine, especially his phrasing and his swing. But also his pronunciation: as Paul’s 1969 solo album That’s Life indicates, he was adept at singing in an American accent. Released by Philips and his only solo album, it was recorded live at the Playroom on Australia’s Gold Coast, and concentrated on late-1960s pop standards. Besides tunes such as ‘Up, Up and Away’, ‘Little Green Apples’, ‘I Left My Heart in San Francisco’ and ‘Lara’s Theme’, the album also includes a medley of hits by Stax and Motown acts, and the Beatles.

Paul was invited to appear on Australian television, but to his regret he was usually asked to perform soul songs, and he felt pigeonholed. “It lost me work in the clubs, especially in the RSL clubs. ‘He’s a soul singer,’ they’d say. Despite the ‘Danny Boys’ and ‘Impossible Dreams’, which I sang in RSL clubs. Because of TV, I got branded – even by clubs I’d been to before.”

Paul’s biggest solo hit was ‘The Ballad of Lionel Rose’ (1967), a tribute to an Aborigine boxer who was the world champion bantamweight; this reached No.11 in the Australian charts.

Soon after his return to New Zealand, Paul became director of the National Māori Choir

Soon after his return to New Zealand in 1990, Paul became director of the 300-strong National Māori Choir, which appeared on the same bill as Kiri Te Kanawa at the opening of the Aotea Centre in Auckland. (Paul says that afterwards, Te Kanawa said backstage “this is the most stunning sound I’ve heard in years”.)

In recent years he has been developing a course in Māori music for use in education. In 2005 he described his goals to iwi radio producer Piripi Walker: “There is a need for infrastructure in the Māori music industry, in more ways than you can imagine. It’s about time we woke up to the fact that we shouldn’t just clone ourselves on other people’s success, but actually learn to do things with a bit of tikanga [correct procedure], and have some kawa [protocol] laid down. So that it’s not just an overnight thing, it’s something sustainable.”

Paul looked back at his period in one of the leading Māori showbands with pride. “It got me around the world, took me to places I’d never be able to go to, and opened the door not only for myself and the solo career that took off in the late 60s after leaving the Quin Tikis, but for all the New Zealanders performing in Australia.”

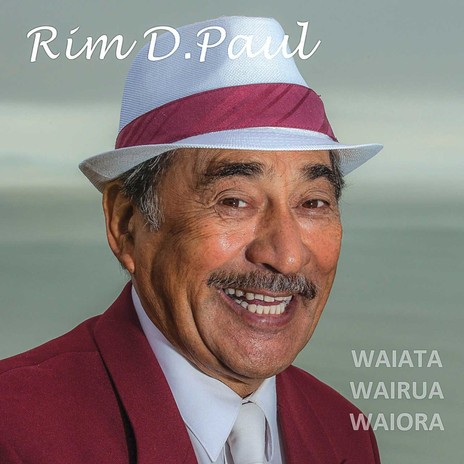

In 2013, at the age of 71, Paul produced his first solo album, Waiata, Wairua, Waiora.

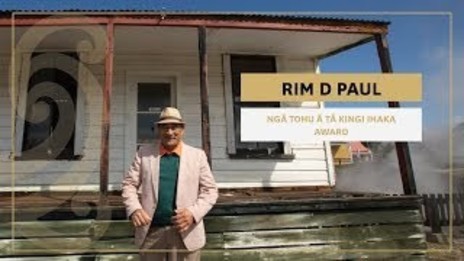

In November 2019, in the Ngā Tohu ā Tā Kingi Ihaka awards (Sir Kingi Ihaka awards) Paul was recognised for his lifetime contribution to Ngā Toi Māori and strengthening Māori culture at Te Waka Toi Awards.