“The Poles Apart is not the most impressive venue in Auckland,” Playdate reporter Tom McWilliams noted in 1967, reviewing the club’s opening night. “It does not try to be. It does try to present material by sincere artists in an atmosphere which is anything but phoney.”

Atmosphere for non-phoney gigs by authentic folk artists was what the Poles Apart achieved for nearly 21 years. Situated upstairs at 424 Khyber Pass, Newmarket, the insalubrious venue hosted gigs at least three times a week for much of that time. Hundreds of New Zealand folk musicians and many international artists shared its tiny stage. When it closed in November 1987, a victim of the 1980s’ rush to demolish any commercial buildings that showed heritage or character, the atmosphere inside the Poles Apart had barely changed.

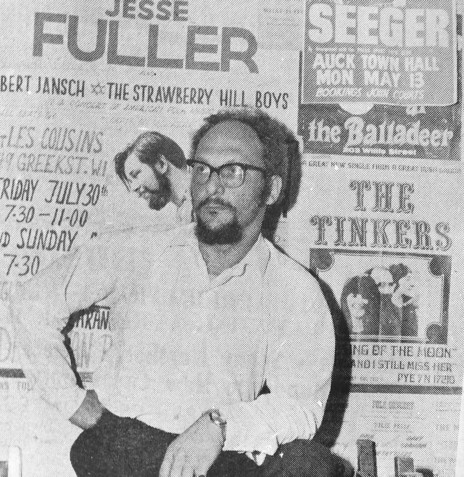

The room was large and cluttered, a T-shape with a low stage; the stage backcloth was brown hessian. In 1987, as the club was about to close, the NZ Herald’s Peter Calder visited and described the scene. “Heavy and rough ceramic ashtrays are dotted around the particle board trestle tables and the motley collection of armchairs and couches have seen better days.” The walls were still plastered with two-colour posters advertising overseas artists whom the club’s management had helped bring to bigger venues such as the Auckland Town Hall: Pete Seeger, Nina and Frederick, the Dubliners, the Spinners.

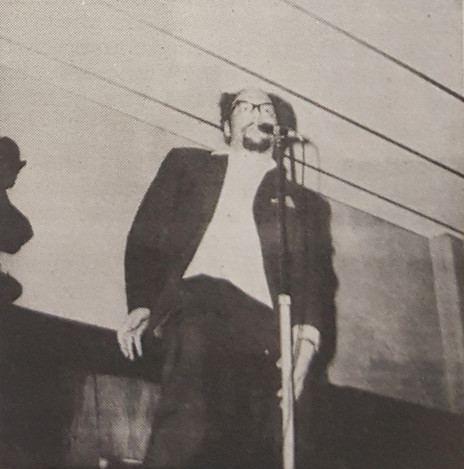

Curly Del'Monte, from Heritage, March/April 1969.

Of all the characters associated with the Poles Apart, none was more dominant or flamboyant than Curly Del’Monte, the club’s founder and original proprietor. Del’Monte was 38 when he opened the club on 14 April 1967 with his wife Stacey; the next day she gave birth to Michelle, the first of their five children.

Del’Monte first got involved in show business in the early days of the Second World War at the age of 11 when he trode the boards in Britain as a singer and comedian. In 1971 he told the Auckland Star that before coming to New Zealand he had been a soldier (fighting for what the Star described as “the Jewish terrorist organisation in Israel at the age of 18,” i.e. in 1948 when it was established as a country), a merchant seaman and a smuggler (running cigarettes out of Tangiers in the early 50s).

His first encounter with folk music was in 1953, at Club 44 on Gerrard Street, Soho, London. Among the many people he met who would become leaders in the folk revival was Ramblin’ Jack Elliott, then playing for two guineas a week. Skiffle was thriving, Del’Monte recalled in 1969, writing in the New Zealand folk magazine Heritage. He witnessed Ewan MacColl playing with his skiffle band, and also saw MacColl at the Round House, Soho, and blues played by Alexis Korner and Cyril Davis, as well as US artists including Big Bill Broonzy, and Sonny Terry and Brownie McGhee.

By the early 60s the folk boom was underway in London, Del’Monte said, “any traditional interest was largely swamped by numbers of young men trying to sing as unintelligibly as possible – the Dylan cult had arrived!”

Curly Del'Monte as MC at the Poles Apart, 1969.

Then known as Curly Goss, Del’Monte took over organising The King and Queen club, which offered a wide variety of roots music: blues, skiffle, jug bands, as well as British traditional folk. Martin Carthy, the Dubliners, and Long John Baldry were among the regulars. (Bob Dylan played there in 1962.) A second wave of artists appeared from about 1963: Bert Jansch, John Renbourn, Julie Felix, and many others, including a solo folkie from the US, Paul Simon. Del’Monte opened a club on Gerrard Street called The Student Prince, and the opening night guest was Blind Gary Davis. He also booked the Round House for a period, and an especially memorable evening was when Julie Felix was one of the main acts. During the night others dropped by to play: Davis, Sonny Terry and Brownie McGhee, Muddy Waters and Otis Spann.

The owners of The Student Prince venue turned the place into a casino, and Del’Monte was given 30 minutes to close – at 1.15am on a Sunday. Within another half hour, he had found new premises on Wardour Street. The audience of 120 people helped move the contents of the Student Prince – singers, books, soft drinks, tickets, sandwiches – and walked through Soho “like Moses and the Israelites”.

Del’Monte decided that he would become his own landlord. Emigrating to New Zealand, he opened the Poles Apart Folk Club in Auckland in 1967. He wanted to run the club on the same lines as the British clubs he’d been involved with, and invited Redd Sullivan – a friend from the Soho scene – to appear on opening night. Unlike many folk clubs in New Zealand then, the Poles Apart was open most nights of the week.

The intention was to feature some overseas artists, and have a resident singer, Bill Taylor, but also to encourage members of the club and others from out of town to perform. Another stalwart of the club was the Hamilton County Bluegrass Band.

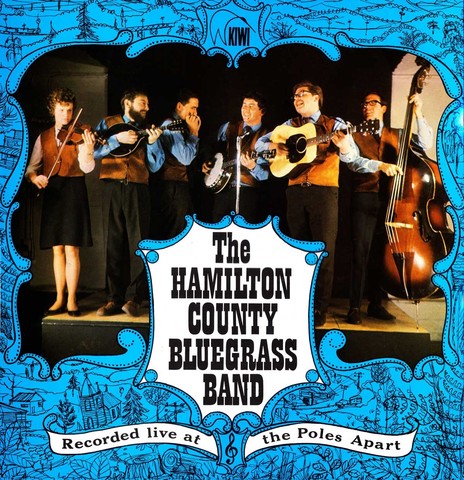

The Hamilton County Bluegrass Band Recorded Live At The Poles Apart album, released on Kiwi, 1967

Visitors from overseas often called in after their performances in larger venues downtown. Peter Yarrow, Helen Ireland, Sonny Terry and Brownie McGhee, and Nina and Frederick were among those who came by to relax – and perform. When the Dubliners visited, the Poles ran one of its “All Nighters”. The club operated a reciprocal arrangement with other New Zealand folk clubs enabling their members to attend, and publicised other folk events, even if they clashed with a Poles Apart evening. The club also held barbecues, inviting other folk clubs, and organised bus trips to visit them. Workshops and guitar lessons were also held.

Annual subscriptions cost $2, and renewals $1; on club nights entry was 25c to members, and 50c for guests (free coffee included). The entry fee increased when an overseas artist or leading local performed.

Wherever there is folk music there is a feud, it seems, and Del’Monte’s forthright approach and policies irritated some of the folk constituency. The accusations seem ridiculous now, and did in 1987 when Calder explained that “Curly’s brash and worldly ways caused more than a few ripples in the purist and traditional folk world. Diehards were appalled at his ‘commercialisation’ of the music, paying musicians and charging for admissions.” Yet big drawcards such as the Hamilton County Bluegrass Band found that recouped expenses – such as travel costs – meant there was little change left for the musicians.

“Curly’s brash and worldly ways caused more than a few ripples in the purist and traditional folk world” – Peter Calder

Also, said Calder, “infighting in the small folk scene was beginning to take its toll. The bad feeling was exacerbated by the artistic turmoil in the world of acoustic music at the end of the 1960s.” US artists such as James Taylor, and Crosby, Stills and Nash showed how acoustic music could be lucrative and, as Dylan had shown earlier in the 60s, folk music could be used for original songs, not just the traditional English and Irish songs beloved by earnest acolytes of Cecil Sharp and Ewan MacColl. “That discovery could not help but harden the battle lines between the old and the new.”

The backbiting towards the Poles Apart was given an outlet in Heritage, when columnist Jean Carmichael wrote “A Spy at the Poles” in 1968. Visiting from Christchurch, Carmichael’s first complaint was about the fee she had to pay at the door. “How much? … heavens, I can keep myself in cigarettes for a week for that!” She described a venue that was as humble as any other, and Del’Monte’s rambling introductions and corny jokes. But she acknowledged his work bringing high-calibre artists to New Zealand. On the night she visited, though, she found “the music was about the standard I was used to in Christchurch – almost.” The difference was the attitude of the performances: witty presentation and “gimmicks of the stage trade rather than, as elsewhere, on the material itself.” The club encouraged more showmanship, in other words.

Carmichael’s main beef was the entrance fee, which she claimed was twice the price of other clubs. She acknowledged that folk devotees had a predisposition to expect their music for as little as possible, but even if the prices were halved, “you would still get the belly-achers.” Her criticism now comes across as provincial, and insecure. Was the club aimed at the well-heeled section of the community? Also, she wasn’t impressed by the Auckland singers: where were the city’s best talents? She thought some regular artists who were present, but not performing, carried themselves with an unwelcoming superiority. Those on stage seemed hyper-conscious of Del’Monte while they sang: they were trying to please him, not the audience or themselves. The club – and its proprietor – deserved to succeed, but the singers needed to deliver their material in their own way. They didn’t have the “saleable stage personality” of Del’Monte.

Curly Del'Monte, 1968.

In a letter headlined “Streets Littered after Poles Riot”, Del’Monte gave a reasonable response pointing out the club was run to support the wider folk scene, offering reciprocal arrangements and collegial policies. “Scandal-mongering, backbiting, and petty personal jealousies will ultimately harm only the music – and the people who indulge in them.”

Respected folklorist and performer Neil Colquhoun responded with an article, “Why I Like the Poles Apart Folk Club”. He compared the informality and warmth of the Titirangi Folk Club – run by Juliet and Des Rainey – with the “church-like awe” at the Uptown Gallery recitals. The Poles Apart shared the same atmosphere as the Titirangi club, with the advantage of being in the central city. Despite paying a higher rent, its entrance fees for club members were no more expensive than Titirangi. The Poles opened four nights a week with the same format: a set by a paid guest performer, preceded by songs from casual and local singers. Originally from Taumarunui, the resident singer Bill Taylor was “experienced and personable”. Consequently, the Poles Apart was very popular and attracted top performers, such as the Hamilton County Bluegrass Band, Phil Garland, and Arthur Toms. The club also offered nights for jazz and country music. One night may have a music-hall atmosphere, with humorous repartee between stage and audience; another might be more traditional, with a intense bond among those present.

Del’Monte, said Colquhoun, was inclined towards traditional folk, but he was a “street Londoner … Like all club-owners the world over he is somewhat of a philanthropist. He is also a businessman … The businessman is needed to stay afloat!”

Del’Monte left the artists alone, said Colquhoun, only interfering when they made the “common error of going on too long”. A silent signal from Curly gave the answer, “and most of us are grateful for that guide”. He was also impressed by the breadth of the audience: the club didn’t just cater for the “folk crowd”, whose intensity he found off-putting compared to, say, the country audience. The Poles Apart, Colquhoun concluded, “is already an unqualified, outstanding success.”

Frank Winter, proprietor of the club for 13 years from 1969.

In 1969 – caught in the middle – Del’Monte relinquished his role as proprietor of the club, “for the sake of the club and the music”. He sold the club for a token amount, “to counter any suggestion of profiteering”. Frank Winter took over, and remained in charge for 13 years. For Calder, these were the club’s “halcyon days, in terms of the quality and quantity of music and musicians.”

Winter was pivotal in the Auckland folk scene for several decades. While running the Poles Apart, he founded the Auckland Folk Festival in 1973, and supported it until his death in 2003. He was well-known for the encouragement he gave young folk and acoustic players, and after his death the Frank Winter Memorial Award for a promising young performer was established at the festival. In the 70s and 80s, acoustic musicians such as Mike Harding, Wayne Gillespie, Denny Stanway, Brendan Power, Mahinaarangi Tocker and the group Acoustic Confusion contributed to a lively scene that had lasting influence. Among those who performed at the Poles Apart in this period were Martha Louise, Peter Madill, Cath Newhook, and Becky Bush.

IN THE 1970S, “THERE WAS A BACKROOM WHERE ALL THE COOL BLUESMEN HUNG OUT AND PLAYED AMAZING BLUES.”

Chris Priestley, who would go on to co-found Real Groovy Records, and the Ponsonby venues Java Jive and Café one2one, told Trevor Reekie that in the mid-70s, “I started hanging out at the Poles Apart Folk Club where the toasted sandwiches were awful and the coffee – which came out of a large urn that had been stewing for hours – was worse, however the music was great, with a concert night every weekend for invited guests and an open night on Wednesdays for beginners like myself. It was run by Frank Winter who was very encouraging to us new folkies and this was one of the few places where you could go and perform. Today there are open mics every day of the week all over town. There was a backroom where all the cool bluesmen hung out and played amazing blues.”

Winter thought the boom would never end, but it did by the early 1980s, and he sold the club back to Del’Monte who, with Stacey and their children, moved into an attached flat.

After his original departure from the club, Del’Monte briefly returned to UK to work in theatre, and for many years was the secretary of the Auckland Branch of Actors Equity. (In 1984 he played a role in the Lynton Butler film Pallet on the Floor, based on the Ronald Hugh Morrieson novel.)

A highlight of the venue’s 21-year-existence was the two albums recorded there. The Hamilton County Bluegrass Band’s Recorded Live at the Poles Apart, and the compilation An Evening at the Poles Apart Folk Club with Redd Sullivan were released on Kiwi in 1968.

An Evening at The Poles Apart Folk Club, Kiwi, 1968

Back cover to An Evening at The Poles Apart Folk Club (Kiwi).

Sullivan was a British folkie, a contemporary of Ewan MacColl and Martin Carthy, a huge man with red hair, a big voice and bluff manner. He performed sea shanties, work songs, blues and music hall, and took top billing on the Kiwi compilation.

But it is the New Zealand artists on the disc who are of more historic interest: the Hamilton County Bluegrass Band (which also backed Dave Jordan playing ragtime), sibling duo Mark and Angela Pedrotti, resident singer Bill Taylor, and local singer Thelma Blyth. A standout act was a throwback to the 1920s: veteran danceband musicians Jim Higgott (banjo) and Charlie Stewart (piano accordion).

Several songs were written about the Poles Apart, and there was also a record label associated with the club, Phreadd. In 1969-70 the label released an EP by an Auckland folk trio the Mark III, and four singles by the Wellington singer Lynne Pike.

Lynne Pike at the Poles Apart folk club, Auckland, 1967

In its latter years, the club broadened the styles of acoustic music it presented, changing its newsletter title to Poles Apart Acoustic Music Club, featuring Folk, Blues, Jazz, Country and Poetry.

The Poles Apart caught the folk boom at its early peak, and rode the wave for as long as it lasted, into the 1980s when – although membership stayed static – audiences tapered off. It had been 20 years since pubs closed at 6pm, and the pub-rock era was in danger of fading itself by 1987. The Poles Apart closed its doors on 28 November 1987. Besides lack of membership growth and a change in live music options, another reason was the rampant development – and demolition – that occurred in the mid-1980s. Del’Monte died in 1999, aged 70.

The club was an ideal venue for the folk singer, McWilliams had predicted in 1967, “because its appeal is not based on extravagant production or synthetic glamour. In a small club the bond between artist and audience is direct and personal … In this close contact lies the authenticity of the Poles Apart – not in self-consciously ‘ethnic’ material. Local talent also benefits from this intimacy. Because there is no artificial barrier, untried performers can make their debut in a sympathetic atmosphere.”

Watch: The Hamilton County Bluegrass Band performing at The Poles Apart in 1968, introduced onstage by Curly Del'Monte.

--

YouTube clips of Curly Del’Monte (family tributes)

Curly Del’Monte recites Sweeney Todd

A Curly Life - by Jaime Gilbert

A video tribute to Frank Winter, by Julian Ward

Folk music at Moller's Farm: highlights from the 5th Auckland Folk Festival, 1978