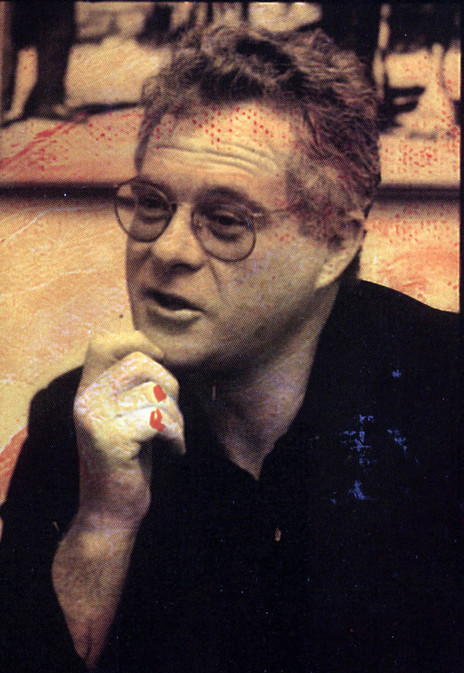

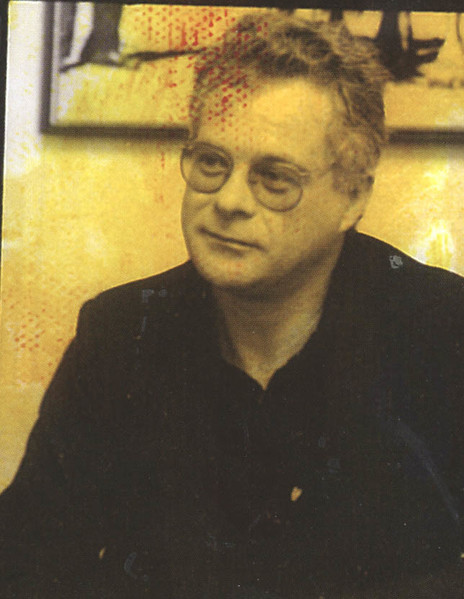

McNabb – who died in 2013, age 66 – was one of this country’s most interesting but often unacknowledged musicians. His only music award came in the late 70s for the self-titled, jazz-fusion album by Dr Tree, the group he co-founded with drummer Frank Gibson Jr.

It won in the rock category but as he would tell Trevor Reekie for NZ Musician magazine in mid 2013, “they re-released it in 2007, buggered if I know why. I certainly never made any money out of Dr Tree, apart from selling one of my songs to TVNZ for a current affairs programme.

“I got $200 for the music, that’s the only accounting of any sort I’ve ever seen from Dr Tree.”

And that was why McNabb disappeared into the studio to record advertising jingles and soundtracks. It was far more lucrative and also allowed him to do exactly what he wanted to do in his own music.

“I had absolutely no compunction about selling myself to the advertising world,” he laughed, shortly before his death from cancer which he knew was going to kill him. “I do them so I can make jazz records. I’ve really enjoyed making commercials. The only thing better [than making jazz albums] is playing live music in an improvised situation. Apart from that, commercials and soundtracks are where it’s at for me.”

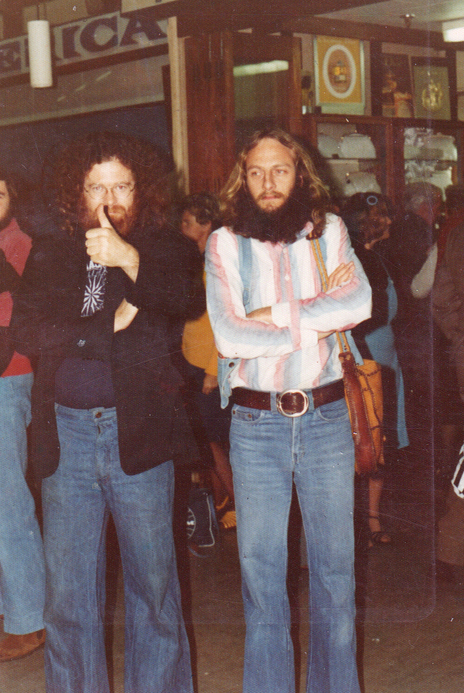

It was my privilege to spend an afternoon talking with McNabb – Gibson by his side – about his life, career and what he knew was coming: “I don’t worry about death, I have my own feelings about that.”

He was funny, feisty, had recently recorded again and was on morphine daily. “I’m on the way out,” he said. “But we’re all on the way out in one way or another. It’s just happening at a different time for me.”

A fortnight later he was gone.

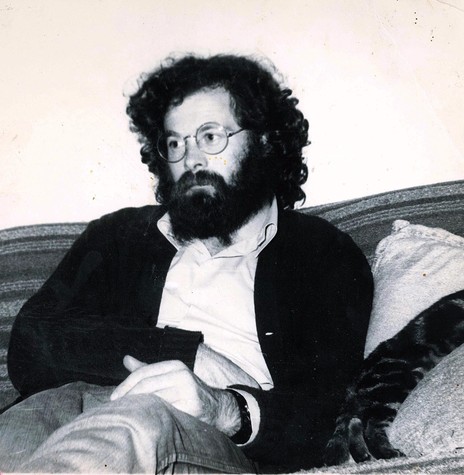

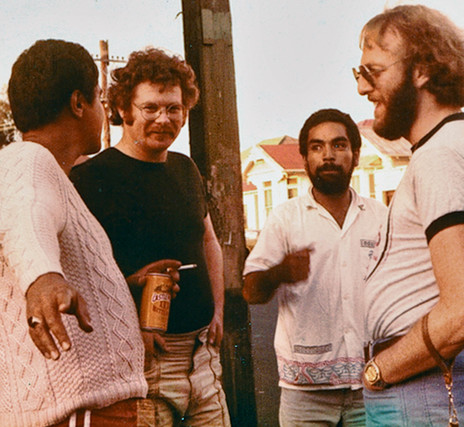

McNabb grew up in Auckland and attended Mt Albert Grammar School which was where he met Gibson, son of the famous drummer. They bonded over jazz, played duets, McNabb largely self-taught on piano. McNabb flirted with pop in the covers band Rainbow (“just chasing the hit parade and keeping up with the Top 10”) and played a bit of country-rock (“I’m not an entertainer, I’m a musician,” he said to Reekie) before he and Gibson auditioned for a gig at the Troika restaurant in Auckland.

When they scored it, he resigned from his trainee accountant job at George Walker’s auction house, and so began a lifetime in music, most often with Gibson at his side or somewhere nearby.

“The idea you can get a degree in jazz just makes me want to puke.”

They played clubs and restaurants (sometimes getting fired for the inventive liberties they took with the tunes), and McNabb said he proudly learnt his craft on the bandstand not in some lecture hall. “Most musicians today teach more than they play. In our era, we always played more than we taught,” he said, with clear determination.

“The idea you can get a degree in jazz just makes me want to puke. If you are going to be a musician, you’ll be a musician.”

McNabb was certainly that and – aside from painting in a powerful and distinctive style – it would be how he would live for the next half century.

He and Gibson were behind one the most important bands in the jazz fusion era of the 70s: Dr Tree, whose sole album won two awards in the rock category.

McNabb joked that, on the night, he was approached by a number of people with the whole “we’ll be in touch” conversation, but nothing happened.

Then – after four years with Dr Tree behind him – Gibson left for a time in London. On his return, he and McNabb formed the longer-lived Space Case in the early 80s; they produced three albums and represented New Zealand at the Singapore Jazz Festival.

McNabb released solo albums under his own name, including a fine trio recording, Waiting for You, in 1987 (with Gibson and bassist Andy Brown); recorded his 1990 album Song for the Dream Weaver in New York with acclaimed bassist Ron McClure (who played with Charles Lloyd, Mike Nock, and Blood Sweat and Tears) and drummer Adam Nussbaum (Gil Evans Orchestra). Back home he recorded with his groups Modern Times and Band R, and arranged the strings for trumpeter Kim Paterson’s album The Duende in 2012.

And after 1979 he was with Murray Grindlay (formerly of the Underdogs and briefly hit-maker Monte Video) and created advertising songs and jingles, many of them award-winning and some real ear-worms: the famous Crunchie commercial set on a stream train, Mainland cheese ads, McDonalds ...

He arranged John Grenell’s ‘Welcome to My World’ advertisement and soundtracks always presented an interesting challenge. Their most important were for Greenstone and Once Were Warriors. Writing for Greenstone allowed McNabb to compose for an orchestra and traditional Maori instruments (played by the late Hirini Melbourne).

McNabb admitted he loved to soak up music of all kinds: “I’ve always been a bloodsucker for any music from anywhere that would expand my music. I’ll listen to music from Macedonia – not a lot – but just to get the idea of what they are about.”

His 2009 album Astral Surfers with Gibson, guitarist Martin Winch, bassist Neil Hannan and saxophonist Stephen Morton-Jones included players on Indian tabla, dulcimer and Chinese erhu.

Much of the incidental music in Once Were Warriors was by the Grindlay-McNabb team from brooding blues to the use of taonga puoro. But of course what most people remember from that bruising film is Tama Renata’s searing and shredding theme music, and the hits by Southside of Bombay (‘What’s the Time Mr Wolf?’), Herbs (‘Homegrown’) and others.

Jingles and film scores were a means to another end: to play jazz or improvised music.

As always, these projects and commissions were a means to another end, to play jazz or improvised music, and he loved being in the studio as much as on the bandstand: “I’d spend 24 hours a day there if I could.”

McNabb’s solo albums could be thoughtful trio jazz releases or sound collages. The opening track ‘Entry’ on his 2000 Band R album The End is the Beginning starts with dialogue from space flights, before including crowd noise from New Zealand vs Pakistan at the Melbourne Cricket Ground which he taped off television and looped. He then added a recording of a person singing at a Korean funeral, which he edited and split.

“Then the electric piano comes in,” he said, laughing. “I like to do stuff like that. “I like to write stuff you don’t have to rehearse, you just start because, ‘I’ve got the melody so don’t worry about it and here we go’. The less you put down [on paper], the more freedom you have.

“I just want to get started. You’ve got to catch the wave. Time to start playing and we’d be away. What do you need to know? ‘It’s in G’.”

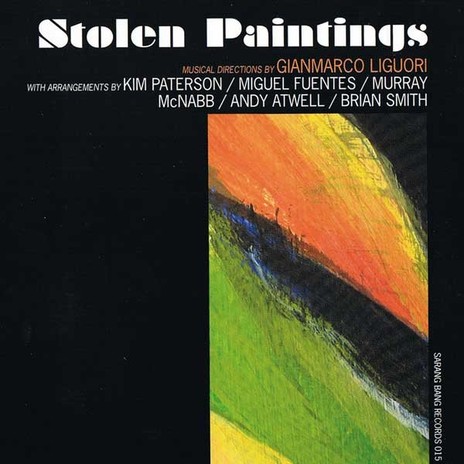

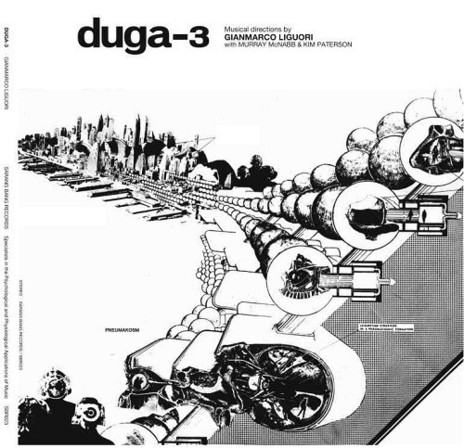

In that he found a fellow traveller in Auckland guitarist Gianmarco Liguori who helms his own Sarang Bang label. Their albums Stolen Paintings (2006) and Ancient Flight Text (2009) reflected their love of the pure freedom of expression: “I just start and you don’t know what’s going to happen. That moment for me is just joy ... and here we go, off into the infinite.”

McNabb was also part of Salon Kingsadore alongside Liguori; their 2012 album Anti-Borneo Magic were “instant compositions” which were followed up by short segments taken from the sessions as “cues for film and television”.

“I started to learn jazz as a boy,” said McNabb, “and somewhere along the way someone said I had to learn the standards, so I thought, ‘Okay, I better learn standards.’

“But gradually the free thing starts to disappear in your playing because you don’t get to be put in a situation where you can do it . . . but here we are full circle with Frank, and Gianmarco in Salon Kingsadore, and playing like that again.”

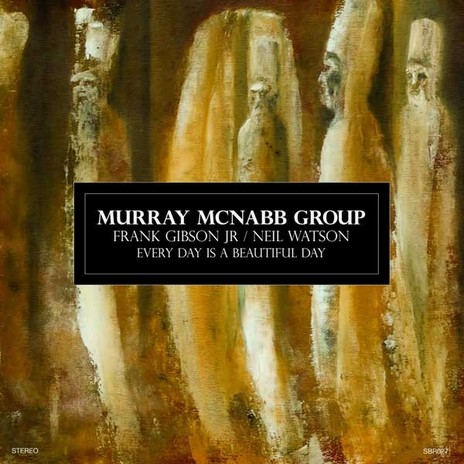

Since McNabb’s death, Liguori has kept the man’s music alive with his final sessions on Every Day is a Beautiful Day (2014, McNabb with Gibson and guitarist Neil Watson) and the release of two majestic, if sometimes difficult, limited-edition double-vinyl albums The Way In is The Way Out (2016, in a gatefold cover of one of McNabb’s paintings) and e-music (2019) of electronic music recorded between 2000 and 2008.

The sheer breadth of McNabb’s music across several posthumous albums defies easy classification.

The sheer breadth of McNabb’s music across these posthumous albums defies easy classification: experimental, out-there, elements of world music and ambient sounds ...

And yes, “jazz” , a genre of fluctuating fortunes in the public imagination.

“That’s absolutely got to do with how many times you see the word ‘jazz’ written in the newspaper, it’s about the perception out there,” he said. “If they never hear the word, [the music’s] not there.”

McNabb might no longer be here but his music of all kinds certainly is, although only three albums under his own name are on Spotify, however others appear under Gianmarco Liguori’s.

From the kid who loved Thelonious Monk through jazz-rock, soundtracks, trio jazz and space-flight experimental instrumental music, McNabb enjoyed quite a lifetime of music. “I am of the peculiar belief that you don’t do anything,” he said in those final days, “it all just happens to you. I never planned any of this.

“I just went along for the ride.”