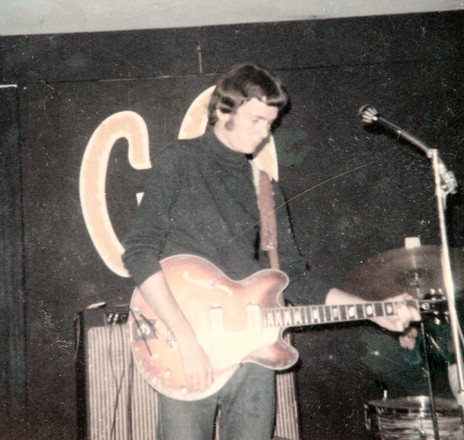

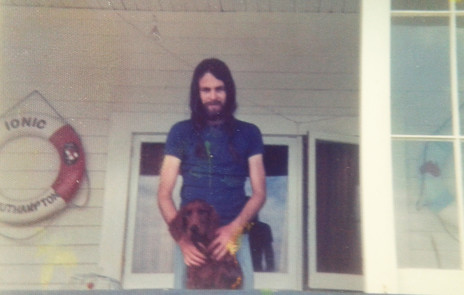

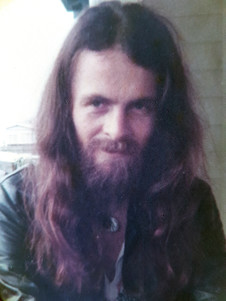

Bruce Andrew Robinson was born 1 October 1945 in The Grange, a northern suburb of Brisbane. He started playing in small jazz combos around the city in the early 1960s before joining The G-Men on bass. They shifted to Sydney in 1965, where Eldred Stebbing saw them. Maggie Parnell-Robinson, Bruce’s wife and partner of 42 years, recalls that his Sydney adventures almost didn’t start. “On the drive south he fell asleep at the wheel just outside Mullumbimby. The car was lucky not to go over a cliff.”

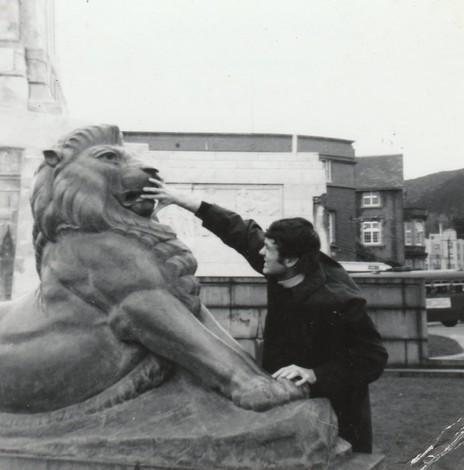

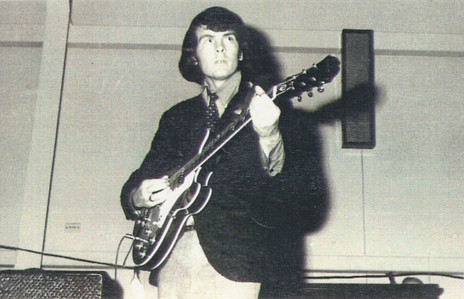

In Sydney The G-Men changed their name to The Pleazers and Robinson shifted to guitar, allowing Ronnie Peel to come in on bass. They arrived in Auckland in August 1965 and although there was some to-ing and-fro-ing across the Tasman and a stint in England, it was in New Zealand where Bruce Robinson was to make his mark.

It was in Auckland, with The Pleazers, that Robinson picked up a nickname that would stick.

There are several versions about how Bruce got the nickname ‘Phantom’.

Maggie Parnell-Robinson says, “There are several versions about how Bruce got the nickname ‘Phantom’, one was that he never seemed to sleep, another was that he sleep walked.”

Shane Hales has his own version.

“We were all living together in this big house and living on a limited budget and we took a shelf each for food. We’d wake up in the morning and someone might complain that an egg or two or some other food had gone missing and Bruce – Bruce always read The Phantom comic – and when no one admitted to pilfering the food, we’d say, ‘Looks like the Phantom has got it.’ And that’s how Bruce got the nickname Phantom.”

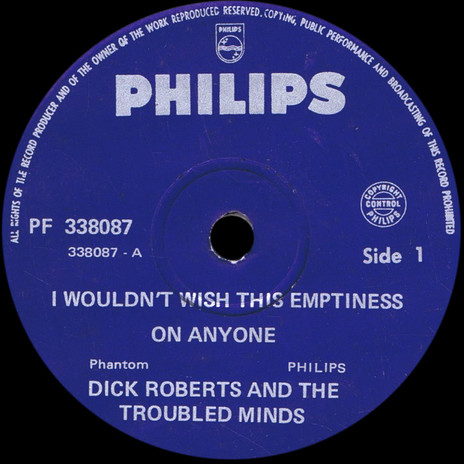

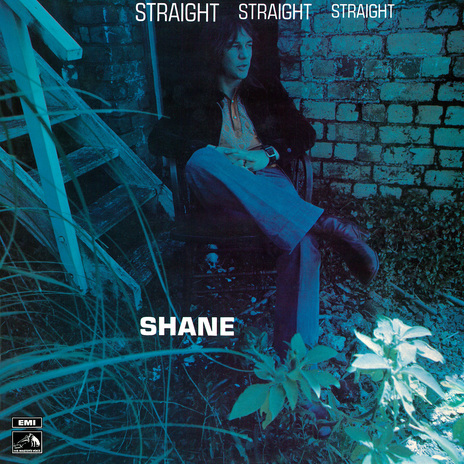

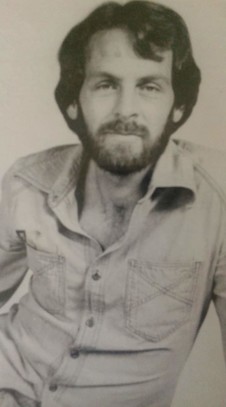

When The Pleazers split up in 1967 Robinson, ever practical, enrolled at Epsom Teachers College. Meanwhile, Shane pursued a successful solo career. In 1969 his regular backing group was The Troubled Mind, from Hawke’s Bay; when guitarist Bob Jackson departed on the eve of a national tour, Shane persuaded Robinson to fill in. He became a full-time member and then Shane’s musical director, a position he held over the next four years.

Alan Galbraith, lead singer of Sounds Unlimited, first met Robinson in 1966, when his band shared stages with The Pleazers, but he didn’t get to know him until a couple of years later.

“I was working at HMV in in Wellington alongside Peter Dawkins and Bruce was Shane’s musical director. He came down for all of Shane’s sessions, usually staying at the flat Peter and I shared in Hataitai. He was a great session musician, disciplined, well prepared, easy to get along with. He was writing good charts for Shane and both Peter and I used him for many of our sessions with other artists. The musical arrangers we used were mostly old school but Bruce was more rock and roll, which was exactly what we needed.”

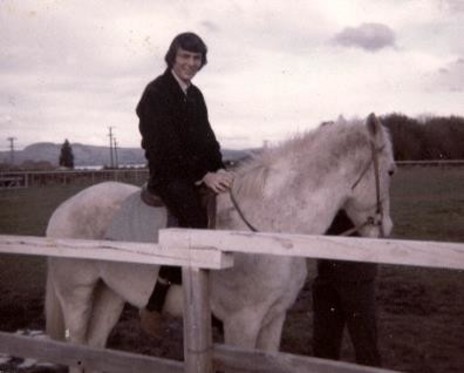

In 1970, at Peter Dawkins’ instigation, Shane and Phantom, plus pianist Rufus Rehu, bassist Rick White and drummer Bruno Lawrence, recorded ‘Heya’, credited to Zonk!, a near international hit. Unaware that it was receiving radio airplay in the United States, Hales and Robinson were on board RHMS Ellinis, en route to Britain, performing to pay their fares.

As ‘Heya’ received radio play in the States, Shane and Bruce were on board ship to Britain.

“It was quite a trip,” Shane remembers. “Bruce missed the boat in Auckland but flew out to Tahiti to catch up. It was only after we’d left New York that we discovered that ‘Heya’ was getting airplay in parts of the US and the record company wanted us to promote it. It was a missed opportunity.” There were other travel adventures. During a later global jaunt, says Shane, “we got lost in Malaysia and locked up in Moscow.”

“In London we flatted together and wrote songs day after day. It was a true partnership and a close friendship. There were occasional gigs, including performances in Germany, and recordings at Abbey Road, which came to nothing.”

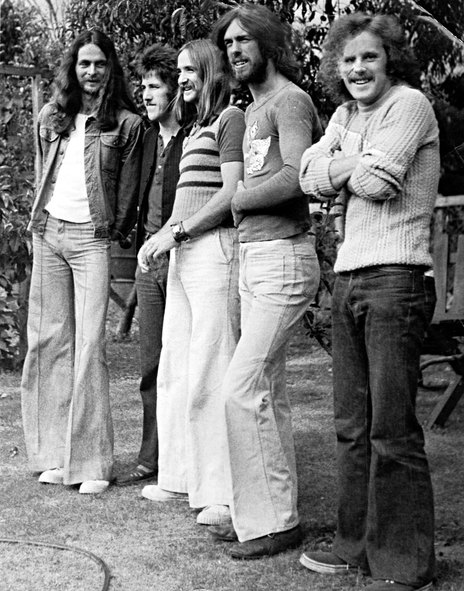

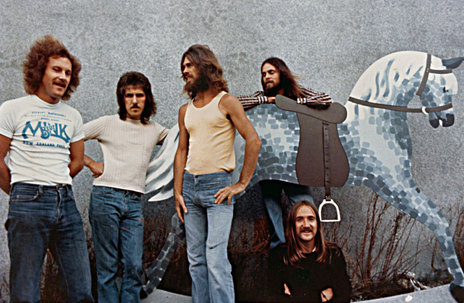

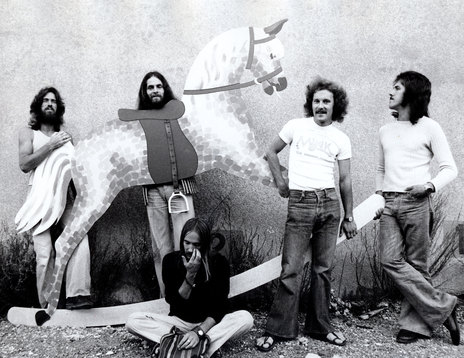

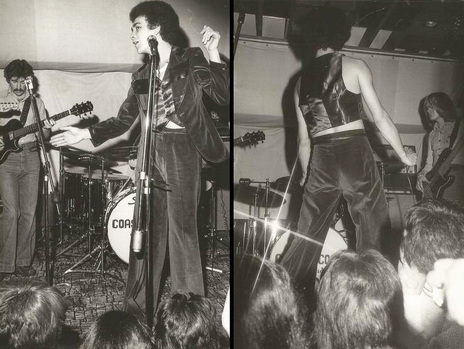

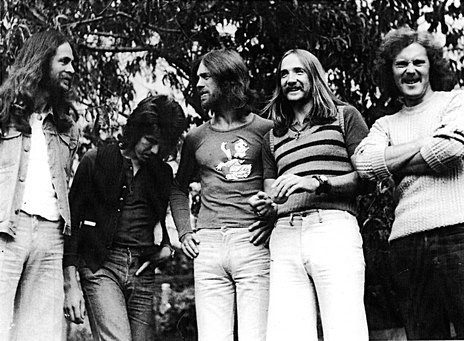

Among the pair’s London social circle were members of The Fourmyula and in 1972 Robinson began playing with Fourmyula’s Carl Evensen (vocals, rhythm guitar) and Wayne Mason (on bass), plus drummer Richard Burgess (ex-Quincy Conserve). They called themselves Flinders. They didn’t last long.

Following a New Zealand tour in 1973, Robinson decided not to return to London with Shane and he replaced Mack Tane in Face, the Northland band which had relocated to Auckland. The lead singer was Mark Williams.

With the band already in disarray, Robinson’s time in Face was brief but he can lay claim to helping launching Mark Williams’ career. Members of The Fourmyula, also in disarray, had returned to New Zealand, unsure what the future held. Guitarist Martin Hope accepted a position in Human Instinct which all but put an end to The Fourmyula but Carl Evensen and Wayne Mason looked around to form a new band. It was Evensen who suggested their guitarist from Flinders.

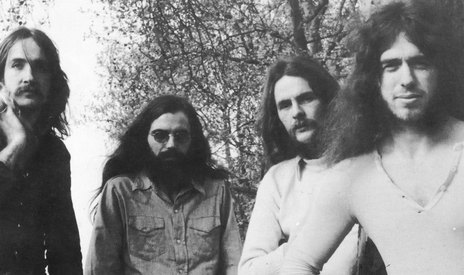

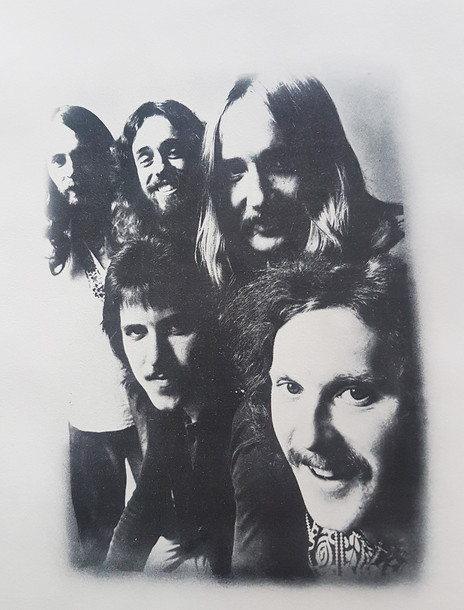

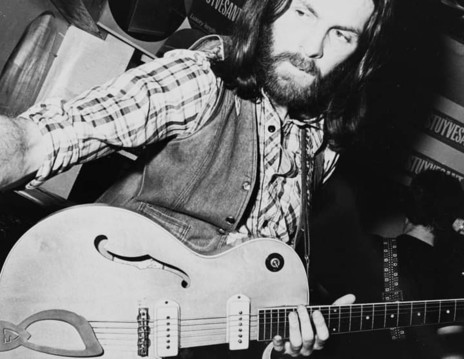

Rockinghorse became New Zealand’s premier country-rock band. Signed to EMI, their third single, ‘Thru The Southern Moonlight’, collected the Best Single Award at the NZ Music Awards and Rockinghorse collected the gong as Best Band. As well as pursuing their own career, Rockinghose was installed as EMI’s in-house band, backing artists like Annie Whittle, the Yandall Sisters and ... Mark Williams.

During the mid-1970s, Mark Williams was New Zealand’s undisputed king of pop, and it was Bruce Robinson who brought him to Galbraith’s attention. Rockinghorse provided most of the backing on those early Mark Williams recordings [Redeye also backed Williams], and acted as his live band.

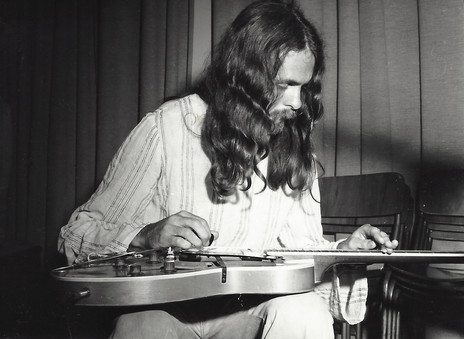

Carl Evensen, who remained a lifelong friend, says, “I always found Bruce’s playing to be quite unique. He was the first bottleneck slide guitarist I’d come across and he gave Rockinghorse a distinctive sound. He could also play rock guitar but he didn’t play that so much, at least with Rockinghorse. He was a very gifted musician.”

Galbraith agrees, “Rockinghorse was a pretty volatile band and I don’t think Bruce really fitted but, playing pedal steel and guitar in Rockinghorse, he was an important part of the overall sound.”

Rick White: “I always found him a little intimidating – tall, aloof, a serious kind of fellow.”

Rick White, who was to play with several Bruce Robinson bands in future years, was employed by EMI at the time. “I worked with Bruce on many sessions and, I have to admit, I always found him a little intimidating – tall, aloof, a serious kind of fellow who didn’t say anything unless he had to. When I had studio work I’d try to get him as musical director and he was always my guitarist of choice.”

The EMI connection led to other work, notably in television. Throughout the 1970s Robinson was musical director on TVNZ’s Grunt Machine and Ready to Roll. Tour promoters, too, sought his talents, and he toured with all sorts, from Kamahl to Norman Gunston.

Following one disagreement too many in Timaru, Robinson left Rockinghorse and walked straight into the Grunt Machine gig. In the new year he joined the Beaver Band, something of a super-group, the burgeoning jazz diva backed by Bruce, pianist Terry Crayford, bassist Mark Hornibrook and drummer Bruno Lawrence. Again, the band didn’t last long, musical trends were changing, but the television and session work kept him active.

In 1983, Robinson enrolled at Victoria University, beginning an academic career that covered criminology, philosophy, psychology, and psychotherapy. He graduated with honours four years later, working as an educator, lecturer and therapist. During this period he played with Stu Petrie’s Silver Dollar Band, with Petrie on bass and Maria McCashin on lead vocals; Rob Clarkson and Paul Whyte were two drummers who passed through.

The Silver Dollar Band enjoyed a residency at The Pines, and there were other outside performances. “We were a straight covers band,” Petrie says, “but there was nothing we couldn’t do, certainly nothing Phantom couldn’t play. And were actually paid very well and we always had a gig. You could say that the Silver Dollar Band paid for Bruce to become a psychologist.”

In the years that followed, as Robinson pursued his academic career, there was always music, bands named Coast to Coast and Legend, lots of pick-up work, occasional sessions, there was Evita and other stage productions. He served time as John McRae’s musical director and was Malcolm Hayman’s regular accompanist in his later years. Rick White says, “Over the course of his career Bruce never liked not to play.”

In 2015 Robinson played on the Andy Anderson’s ‘Andersongs’ album: they were his last recordings.

In 2015 Robinson joined Andy Anderson’s band and he played on the Andersongs album, released after Bruce’s death. They were Bruce Robinson’s last recordings. One of the songs is titled ‘All Rise (Phantom’s Song)’.

It’s somewhat fitting that Bruce Robinson’s final recordings were with Andy Anderson. The pair had first met, albeit briefly, in Sydney in 1965: Bruce was in The Pleazers, Andy was lead singer of the Missing Links, two of the wildest bands around. It was the arrival of Links’ bassist Ronnie Peel in The Pleazers that led to Bruce switching to guitar.

Rick White says, “Bruce was a phenomenal talent and I always felt it an honour that he wanted to play with me. And he was always reliable, he arrived on time, his gear always worked. Bruce Robinson was always a quiet achiever who didn’t put himself forward and never sought the limelight, the classic number two guy, the go-to guy, the glue in the band.”

Alan Galbraith says, “When I met Bruce in 1966 I had just joined Sounds Unlimited and he came down to Wellington with The Pleazers. They were a rowdy bunch of bastards but there was this one big tall, quiet guy at the back who looked a bit more serious. I learned later that he wasn’t just a great musician but a wonderful human being with strong socialist beliefs who cared deeply about many things. I will always remember him as the chin stroking, deep thinking, quiet one, never wanting to offend, always a bit mysterious, hence the name ‘Phantom’ I guess. He was not really your regular rock and roll guy.”

Bruce Robinson died suddenly following a stroke on 31 July 2016.