Nothing seemed insurmountable for Lee. Early in his career when he was hired by the Auckland bandleader and unionist Bert Peterson, it seemed his arrival would put several musicians out of work. Peterson commented that Lee only played alto and tenor saxophone, trumpet, trombone, drums, bass, piano and piano-accordion: “He makes up for this this by singing the vocals.”

Lee was born in Dunedin in 1923. When he was four years old, a brass band visited from Auckland: it was from the Jubilee Institute for the Blind, and they let him beat the bass drum. Within a year he would be living at the Institute, a 48-hour journey from home by train and boat. He was just five, and it was too early to leave home, he later said. He was scared. But the institute was the making of him. He learnt music from a teacher who was also blind, Vivienne Martin. She taught him piano – rapping him over the knuckles if he made a mistake – and how to read music in Braille. Lee became a member of the Blind Institute’s brass band, and also – at the age of 11 – its dance band, which toured New Zealand to raise funds.

In a programme called Stump Julian Lee, he was given the name of a song and was expected to perform it live to air.

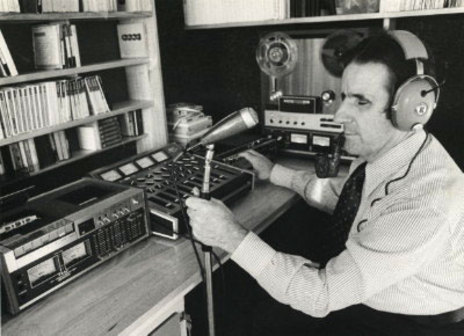

When he returned to Dunedin in 1938 he was billed at the Empire cinema as “Master Julian Lee, at the console of the mighty Christie Organ”. He was recorded at the 4YA studios performing with Christchurch bandleader Martin Winiata, and became part of the 4ZB “radio family”, working as a DJ, operating his own equipment. In a programme called Stump Julian Lee, he was given the name of a song and was expected to perform it live to air.

By the early 1940s he was heading north: A stint in Wellington playing trumpet at the Majestic, and piano at the Roseland cabaret, a year in Wanganui playing dances with musicians from Rātana pā. He was wooed back to Auckland in 1945, playing almost every night of the week with the leading dance bands and the 1YA radio band.

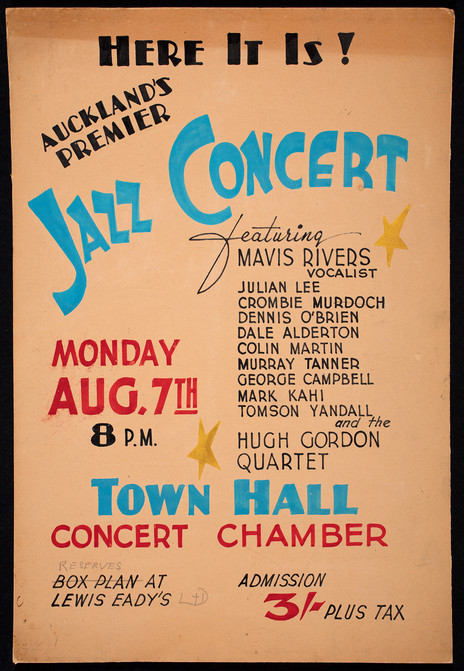

By 1950 Lee was adept at bebop, quickly becoming one of Auckland’s leading exponents. In August 1950, there was a landmark concert at the Auckland Town Hall Concert Chamber that showcased the best of our jazz musicians. It was for listeners, rather than dancers, and they heard players such as Crombie Murdoch, Colin Martin, Mark Kahi and Johnny Bradfield, as well as singer Mavis Rivers. Lee wrote many of the arrangements, and mostly played alto, but the track ‘Messin’ Around’ was a virtuoso showcase: He took solos on tenor sax, trombone and trumpet.

Rivers and Lee would work together often when he became the musical director for Stebbing Recording Studios in 1952, based at Pacific Buildings on the corner of Queen and Wellesley streets. While there he produced and arranged records by pop, jazz and country artists – and also released some novelty songs credited to names such as Julian Lee and His Symphony of Magic Pianos, the Zodiac Mellotones and Sir Hugo Holme.

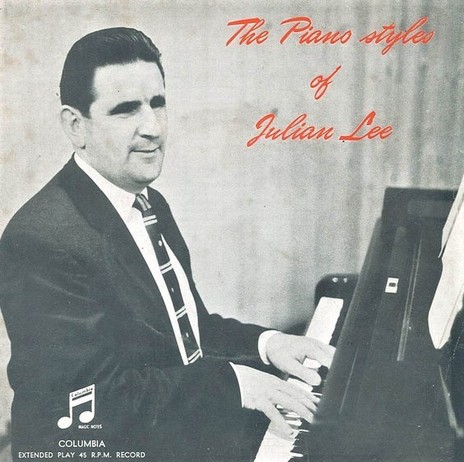

The breadth of Lee’s talent seemed limitless and his influence was felt by players throughout Auckland. He could be heard on radio playing popular songs with his group the Electrotones, standards with his Quartet, and alto saxophone with Bob Leach’s radio band. He also produced singer Esme Stephens’ hits ‘Mixed Emotions’ and ‘I Love You Because’.

While at Stebbing, Lee enjoyed challenging the boundaries of recording, pioneering techniques such as multi-tracking, and using unusual keyboards such as 1YA’s Novachord (like a primitive synthesiser, it was made by the Hammond Organ Company).

Lee moved to Australia in 1956, playing piano for a hotel chain until he started writing arrangements for ABC radio and jingles. Visiting musicians such as jazz pianist George Shearing (who was also blind) and Winifred Atwell were impressed by his talents and tried to woo him overseas. It took the Chairman of the Board to encourage Lee to venture further afield: Hollywood.

Lee borrowed a trumpet so he could get through security for his meeting with Sinatra.

In 1999 he told the story of his encounter with Frank Sinatra to Radio New Zealand’s Haydn Sherley: “Frank said, I’d like to have a chat with you, so if you could come backstage this evening before the show, we can spend the first hour having a talk while the support act is on.” Lee borrowed a trumpet so he could get through security for his meeting with Sinatra, who told him: “I’ve heard some of your things, I want you to come over to the States, in fact you have to do that because you’re a talent we want to foster.’ So I said, ‘Well, what señor commands I must do’.”

In 1963 Lee headed for the US with his Dunedin-born wife Elaine, who was his musical assistant. Although he didn’t work for Sinatra, the connection opened many doors, and sessions with Gerry Mulligan, Chet Baker and others followed. An especially helpful ally was Shearing, who hired him to transcribe his arrangements in Braille – a rare skill that helped Lee’s immigration status.

Based in Hollywood, Lee became a staff producer and arranger at Capitol Records but in 1974 when the first oil crisis increased the costs of the record business, those working in the less fashionable areas of music were let go. He returned to New Zealand, spent four years working at the Blind Institute and mixed once again with his former jazz colleagues. He became a stalwart in the Auckland Neophonic Jazz Orchestra, an all-star ensemble that featured well-known names such as Crombie Murdoch, Merv Thomas, Murray Tanner and Jim Warren. He also produced and arranged several pop and rock acts, among them Think, the Yandall Sisters, Mark Williams, Malcolm McCallum, and Toni Williams.

For the 1974 Tauranga Jazz Festival, he formed the Julian Lee Trio with a rhythm section from the next generation: Frank Gibson Jr on drums and Andy Brown on bass. Their partnership continued in 1976, when they collaborated with leading Australian jazz players Don Burrows and George Golla, calling themselves the Tasman Connection.

By the late 1970s, Lee found there wasn’t enough work in New Zealand, so he returned to Australia. Among his last hit records were two albums he produced and arranged in Sydney for fellow expatriate Ricky May in the early 80s. May sang jazz standards, many of them associated with Fats Waller and Louis Armstrong, accompanied by the Julian Lee Orchestra. It was a meeting of two of New Zealand’s greatest jazz talents that showed there was no generation gap.

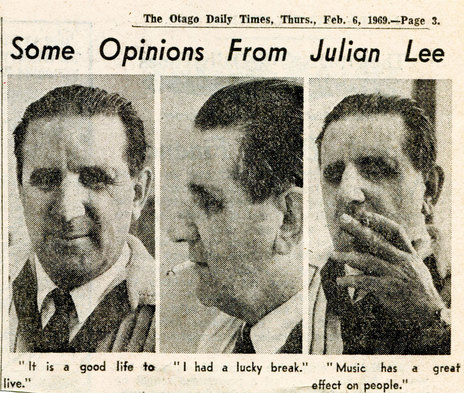

Blindness never got in the way of Lee’s career. Work kept coming his way, he joked: "One door opens, another slams in your face.” He has even said his blindness gave him an advantage: It meant he got musical training that he would never have been able to afford if he had been sighted. He was also conscious that his listening skills were exceptional. “My ears have been my salvation, really,” he said in 1999.

--

Julian Lee died in early December 2020, aged 97. He spent his last years in retirement in rural New South Wales, occasionally turning out to play piano locally.