AudioCulture

The noisy library of New Zealand music

Te pātaka korihi o ngā puoro o Aotearoa

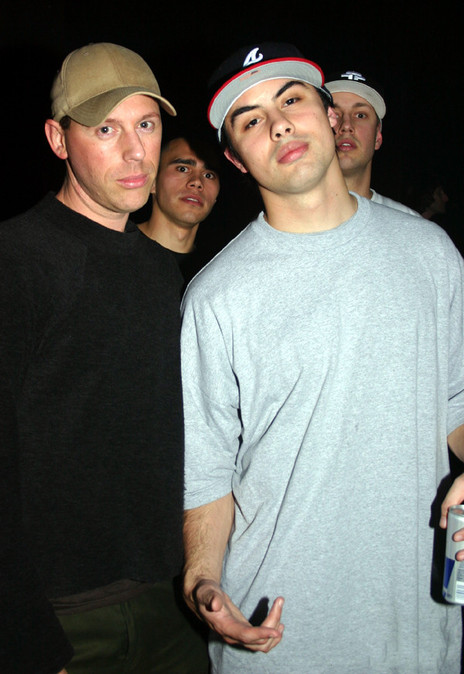

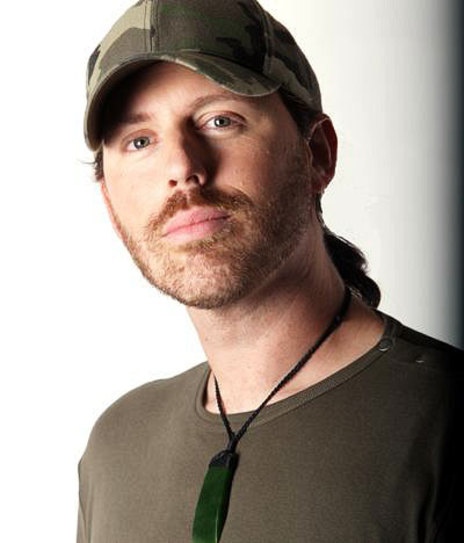

Chris Chetland

Start ferreting around for information about Chris Chetland, however, and you soon get dizzy at the multiplicity of endeavours the label owner, studio owner, musician, producer and mastering engineer has taken on. And in fact, just as you think you’re starting to get your head around Chetland, he’ll casually mention some other curious collaboration.

Let’s not even get started on his non-music passion: in his spare time, Chetland is the editor of a theoretical biology journal. (Cue gasps of astonishment).

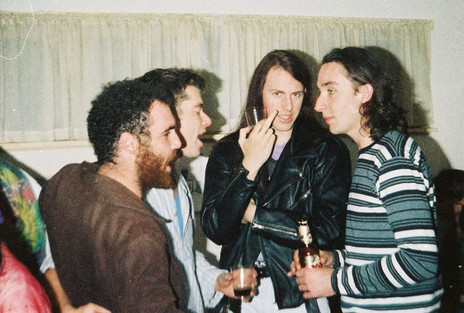

Growing up in Howick, Chetland was one of a group of young men, long hair flowing, gravitating away from Auckland’s suburban sprawl towards the city fringes in the early 90s, and getting off on the aggressive metal-electronic hybridisation of groups such as Ministry and Skinny Puppy.

The influence of metal on electronic dance music is seldom discussed – a kind of dirty little secret

“I was a bit of a metal head, but I was also into electronic music at the same time. I just liked the sound,” says Chetland. “The intensity of metal was equally comparable to electronic bands like Skinny Puppy and Front 242. I was listening to a lot of that, and Nick Cave and the Birthday Party … usually the more intense styles.”

The influence of metal on electronic dance music, and particularly that of the prolific Kog label, is seldom discussed – a kind of dirty little secret to those who prefer to refer to the usual techno or house music lineage – but Chetland soaked it all up to form what would become something of a label aesthetic.

First though, in 1993 his rite of passage meant rubbing shoulders with inhabitants of a warehouse flat at 398 Great North Road where the Kog collective slowly coagulated, and which saw Kog-connected individuals – among them Nick Meikle, Nick Wilson and Bruce Ferguson – come and go.

“There was a group of people putting on the first warehouse dance parties that any of us were aware of, and it was really cool because we were exposed to a whole lot of new dance music, like early techno and trance, which would be playing in one room while things like Ministry would be playing in the other. It was really exciting. There was a big interaction of people, because nobody knew what it was or how to define it, and it didn’t have the compartmentalisation that developed later on.”

Inspired by the techno, trance and drum’n’bass being DJ’d, they began adding electronic elements to their own music.

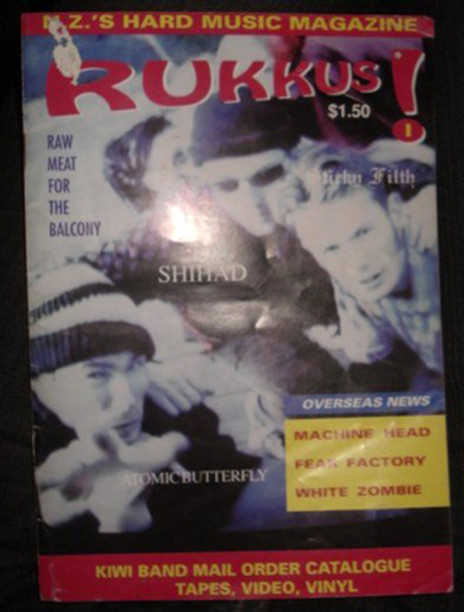

Chetland’s own metal band, Raw Meat For The Balcony – for which he contributed keyboard samples and programming – eventually grew big enough to score supports for Pantera and Sepulchura, but also played at warehouse events. Inspired by the techno, trance and drum’n’bass being DJ’d, they began adding electronic elements to their own music.

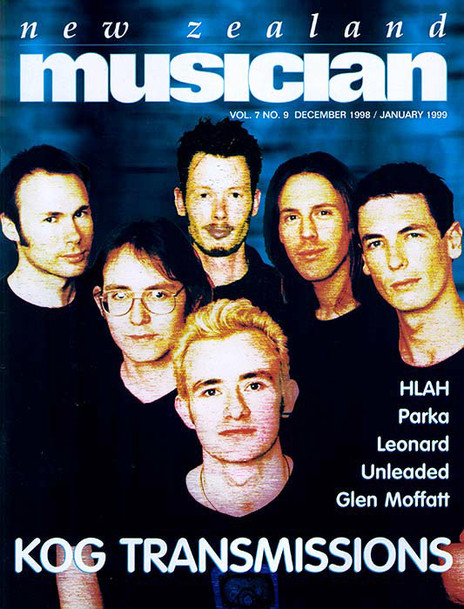

It was when he moved to a flat in a dusty old former shoe warehouse at 509 New North Road in Kingsland that many of the alliances that led to the Kog collective were made, and it was there that the Kog Transmissions label would set up its studio and HQ, with a primary team comprising of Paul Hammond, Pat Hammond, Andrew Manning, Dave Fisher, Pete Collins and Bruce Ferguson. As they became more successful and industrious, Hamish Walker, Leyton, Joost Langeveld, Mark Kneebone, Damian Vaughan, Anne Larnach and Callum August were added to the team.

In 1996, they started building the studio. “We had no money, just student loans. We got all the wood from the demolition yards down the road, and we’d stay up late de-nailing all the wood. We wanted to record our own metal album, and experiment with how we could cross over the electronic stuff with the metal, but because recording was so time-intensive, there was no way we could afford to do it in someone else’s studio.”

Although Chetland and his mates soaked up the more urban dance styles favoured by club gurus such as Simon Grigg, and Grant Kearney in clubs like Box, they preferred the giddy, psycho-active “techno-trance” music of underrated local electronic artists like Ben Harris, Greg Wood and Denver McCarthy.

“They would have so many synths it was almost impossible to get them all working for a live gig, but there was a really good group of people doing that music. Denver McCarthy was the focal point for the genre that engendered New Zealand electronic music production, and he got it right.”

Chetland is quick to acknowledge, however, that in the early days of New Zealand trance and festivals like The Gathering, “we were still in metal bands and would turn up in leather jackets with beers to the odd weird look,” although towards the last days of the Nelson-based festival, Kog helped release a few Gathering CDs.

That genre-melting Raw Meat For The Balcony album failed to make more than a ripple (it’s now available online), but what did come out of the Kog studio was an amazing burst of sustained industry and creativity from 1997 to 2003, when the wheels slowly started coming off what was always a very informal, somewhat ad hoc association.

At its peak, Chetland was running the Kog studio – which he had quickly established as one of the best mastering facilities in New Zealand – and Kog Transmissions had spawned a raft of sub-labels like Midium, Dirty and Reliable.

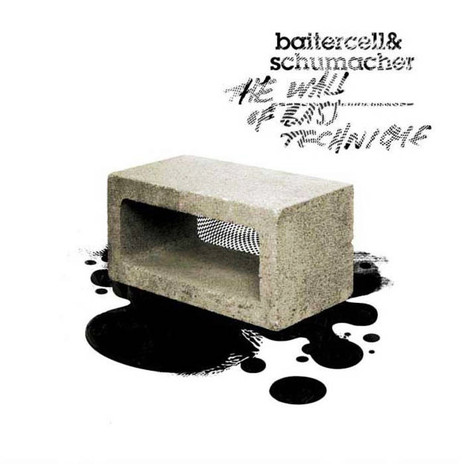

Somehow, he also poured his creativity into his own Baitercell project, which he describes as “break-beaty or drum and bass, but more psychedelic sounds-wise… the album was us working with Bex Riley as well as a lot of the hip hop guys around at the time. We thought it would be interesting with their syncopation to do hip hoppy stuff with electronic sounds. The resulting album The Wall Of Bass Technique was a finalist in the New Zealand Music Awards’ Best Electronic Album category in 2005.

Kog’s killer punch was Micronism’s Inside A Quiet Mind, a sleek, world-class work of minimal techno

Kog Transmission got rolling with the Transmit compilation, followed by Chetland’s dub project with Andrew Manning, Chumbwa, and then the killer punch, Micronism’s Inside A Quiet Mind, a sleek, world-class work of minimal techno.

“That’s the one that really opened it out,” says Chetland. “That was a work of genius on Denver’s behalf, and it almost killed us. There was so much de-noising to do. A week and a half of just getting all the hiss out of it. Denver had recorded it on old analogue gear which is very hissy, and because he’s such a quiet, gentle guy he never wanted to push it, so he kept his levels really low. So the signal to noise was really low. Pete and I worked on that and it almost destroyed us, the number of hours we had to put into it.”

Soon, product would be pouring out. Artists such as Pitch Black, Concord Dawn, Avotor, Epsilon-Blue, Rotor+, Subware, Shapeshifter, and Chetland’s own project Baitercell all released through Kog Transmissions or one of its sub-labels. In addition, there was a successful series of compilations – Algorhythms and Dub Combinations – that helped introduce new artists.

What really set things on fire for Kog was a simple but successful strategy: whenever they held a party to launch a new album, that CD was part of the ticket price, and was given out at the gig. The idea was inspired by the Theory of Increasing Returns by complex systems theorist Brian Arthur.

Chetland attributes Kog’s early success to the focus and conviction of a team of young men and women who were willing to put their all into the project.

“We’d done our first release,” explains Chetland, “and I knew it was going to be six months before we got our money from sales in the shops, and that it wouldn’t work as a sustainable model for us. And then I remembered a theory that I’d studied about how to build a system that would self-organise and then do much of the work for you. So we set up a plan where we got the CD pressed, and then we had the release party after the CDs came back and before the 20th, so we got the money on the night to be able to pay the bill. So we could keep on leapfrogging, because we had to get a huge catalogue and number of albums out to everyone in a quick burst, so that people actually knew there was a movement in New Zealand electronic music, and would take it seriously. It was a numbers game. And we weren’t going to do that by individually selling them here and there and there. We needed to get everyone in one place and make sure they all had a copy, but also psychologically make sure they all really had a good night, and party with it so they talk about it. So we just turned the standard model around.”

Ultimately, however, Chetland attributes Kog’s early success to the focus and conviction of a team of young men and women who were willing to put their all into the project.

“A group of guys, the main crew, didn’t have anything much else to do but work at this. It’s that whole thing of being in your mid-to-late 20s, and you’ve got to prove yourself in the world and you’ll just keep on working, bashing your head against the wall until you see some results. People in those situations together often bounce off each other to keep on doing the hard work, and they’ll be super-focused on that. It’s a youthful thing, energetic, single-focused.”

Chetland still has no easy explanation for why Kog Transmissions started imploding in 2003.

“There are a number of things,” he says. “It grew so fast and had so many input factors, and anything that does have that many inputs from that many sides pushing from that many directions is going to blow the central core of itself apart. That’s a foregone conclusion, but that splinters off a whole lot of new seeds to grow. We were releasing so much, and it was ‘you should do this’, ‘you should do this’, coming from everyone in different directions, which creates a lot of displacement and incohesiveness. And we were trying to develop UK distribution at the same time, and we got totally taken for a ride by one of the distributors for a lot of money, which all went up their nose, apparently.”

P-Money’s Big Things (2002) had been a major seller for Kog, but in 2003 P-Money left with Callum August, and Mark Kneebone severed his ties, running the Tardus label from Universal. This loose aggregation of talent had fractured and dissipated, leading to the demise of Kog Transmissions as a working label.

Chetland kept the Kog name and studio, however, and continued with his mastering activities. “I was more into things as a sonic palette.”

Chetland kept the Kog name and studio, however, and continued with his mastering activities. “I was more into things as a sonic palette, first and foremost,” he says. “That’s probably why I fell into mastering, because you’ve got to take that step out and hear the aesthetic moment of the track, rather than the pinpointing anything in particular.”

These days, Chetland runs Kog out of a custom-made studio on his Titirangi property, where he lives with his wife – musician and music publicist Huia Hamon – and their two young children.

It seems the ideal existence for an eco-aware biologist, with a view of regenerating indigenous bush and a vegetable garden at the back of the house that serves as a fresh larder for visiting musicians.

But what happened between the end of Kog and now? Chetland explains that in 2007, he decided to get back into the academic studies that he had given up to take on Kog in the mid-90s.

“I felt I should get back into doing some more academic stuff, because my brain was atrophying, so I smashed out a Masters, then started a PhD.”

That led to his continuing study of evolutionary theory, and his invitation to be one of the editors of the Theoretical Biology Forum Journal, as well as helping to release and contributing chapters to books in Theoretical Biology.

“My main thing is applications of philosophy of consciousness to evolutionary theory – how the mind constructs our perception of the world specifically in relation to organisms, because it seems we format space and time within our heads, we make a construct that forms our perception of reality but doesn’t completely cohere with the actual thing. And the main problem with a lot of current models of evolution is that they’re running into some significant explanatory problems due to this conceptual gap, so we need to develop new systems and theories to account more accurately for the phenomena. Much in the same way that general relativity and quantum physics took over from and enhanced our understanding from the Newtonian model.”

It’s easy to see how this line of enquiry gives Chetland’s intellect a workout that music can’t quite achieve, but that doesn’t mean it’s any less important to him than it was. His state-of-the-art monitors and acoustically near-perfect studio are proof of that.

As for the mastering, which is anything but a perfunctory mechanical job for Chetland. “It’s better to be there with an actual human, but I do jobs for people all around the world now. We can stream live from the studio in CD quality, so it’s really picking up. Working with people in real time in different countries or cities is really exciting.”

While Chetland acknowledges the huge sea-change away from expensive studios to home recording, he reckons that massaging an album to life in post-production is still absolutely essential, and his work often involves a deeper communion with the artists he works with.

One such is Hawke’s Bay instrumental trio Jakob, with whom he worked on their last album, Sines in 2014. Chetland compares singles with “plants like coriander that only last a few weeks” and albums with kauri. “There’s still very much a movement of that, people who see it as a process, which an album is, a journey rather than a snapshot. They’re going to keep producing albums, because they can’t not!” And he speaks from experience when he says, “I’ve got so much respect for anyone who completes an album, because it’s one of the biggest emotional self-discovery journeys you’ll ever go on. Especially if you’re trying to do it properly, it gets right down to the core of you, and makes you bare.”

With mastering, he says, “You get to go deep into that space. It’s a beautiful journey, because I see artists at the end of their album, and half of my job at least is psychology, teaching them how to let go and also where to go back and do little parts of it differently, helping with the final thing, because it’s so hard to go ‘I’ve done this album … I think. Is it ready to go out?’ The Jakob album took six years, and we took months just finishing off the mastering and trying things out, just to get it to the level that an artist can let go.”

Chris Chetland has mastering credits on many hundreds of releases, including international acts such as Dua Lipa and Bebe Rexha. He also continues to work alongside new artists, notably the bilingual (English/Te Reo) rapper Rei whose song ‘Good Mood’ – engineered and mastered by Chetland – has streaming stats up in the millions.

Visit our sister site

NZ On ScreenMade with funding from

NZ On Air