Opposites attract. Free, with his cochineal hair colourings and Karekare hippie trimmings and his fascination in the cosmic trails of Richard Nunns’ taonga pūoro. Hodgson, who grew up entranced with the “strange fuzzy noise coming out of the shortwave” and has said: “A burst of static is just as powerful as a good tune.” Free, whose keyboard and programming skills and experience working in everything from jobbing pub bands to producing Salmonella Dub, to giving a helping hand to the likes of Neil Finn and writing music for TV comedy and children’s shows (deep breath) all surely contribute to his popular touch. And Hodgson, whose seminal Christchurch industrial group Tinnitus reflected, and helped to develop his interest in immersive, spatial ambient textures.

The duo performed their first gig at the iconic Golden Bay/Takaka Hill trance festival The Gathering, and built up a live following around the country with down-tempo but hypnotic live shows incorporating Hodgson’s deftly triggered visuals.

Mike Hodgson recalled Pitch Black’s debut performance at The Gathering: “When you’re as gone as the audience, then you’re going to transcend the moment. I’d been up for two and a half days, when we played The Gathering, and I was completely stuffed. At the end of the gig, I felt like I’d had a night’s sleep, it was a blinder, and I carried on for the rest of The Gathering without having to go to bed. In one hour, because the creativity was so special and amazing, there was this packed audience, they were screaming, jumping up and down and carrying on, the visuals were going off … I wasn’t even at the gig, I was somewhere else having a sleep, and I woke up at the end of the gig completely refreshed, like I’d been to bed. It was amazing, special, exciting.”

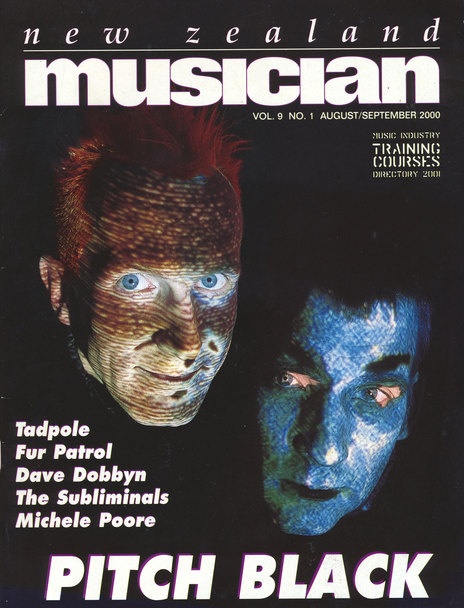

Futureproof was a sneaky hit, and a solid exposition of the Pitch Black sound.

Their album debut crept onto the shelves of independent record shops in 1998. Futureproof was a sneaky hit, and a solid exposition of the Pitch Black sound, which some called “digi-dub” because its sonic canvas was draped with dub delays and hallucinogenic irruptions. Rhythmically, however, it dipped into drum ‘n’ bass, breakbeat and techno territory. The combination was a feel good success, and the twosome would go on to make four more album-length iterations of the Pitch Black sound, each one more sophisticated and streamlined, along with a number of remix projects.

Long before Fat Freddy’s Drop, Pitch Black showed that it was possible to create a large groundswell of support while remaining resolutely underground and untroubled by the usual business machinations. Their gigs were audio-visual events, but to their credit, they managed to avoid the big gesture excesses of international groups they have been compared to (Underworld, Orbital), creating instead a hypnotic framework for slow dancing or head nodding.

Paddy Free’s sense of good-time grooves always lets the light in to balance against Mike Hodgson’s more emotionally unsettling textures.

At the beginning, Pitch Black was a side project for Paddy Free, whose main group Mesh was wowing audiences with its “live organic techno”. (Former Mesh man Brother J contributed a vocal to Pitch Black’s 2007 album Rude Mechanicals.)

As a young fellow, apart from enjoying the “strange fuzzy noise coming out of the shortwave”, Mike Hodgson’s other favourites included classical music, and early synthesiser gurus like Tomita and Wendy Carlos. His eye-opening early concert experiences included The Gordons, Children’s Hour and Fetus Productions.

Named after the only really good Vin Diesel movie, ever, their moniker suggests something dark and threatening. But really, Paddy Free’s sense of good-time grooves always lets the light in to balance against Mike Hodgson’s more emotionally unsettling textures: check those out, for comparison, on the almost beatless atmospheres of his solo project, Misled Convoy.

The duo further elaborated when I first interviewed them in 1998:

“My roots are noise, art, sound sculpture, not music,” said Hodgson. “For me it’s dance music, music that switches off the conscious mind, and anything that’s groove or rhythm oriented,” said Free. “We’ve got one foot in trance, one foot in drum ‘n’ bass, one foot in ambient, one foot in cinema, one foot in live, one foot in studio,” said Hodgson, leaving aside any discussion about how many feet he had hiding in the pockets of his trousers.

Discussing the live show, he said: “Our definition of live would be that we’re fully and utterly in control of the machines. We have structures, but every individual piece that builds the block can be mutated, altered; we can turn a stonking full-on dance track into an ambient track at the flick of a button, and I’m much more interested in producing an emotional effect in a group of people than satisfying them with some sort of dance aesthetic.”

And the visuals? “I can never separate sound and images,” said Hodgson. “I’ve got ears, I’ve got eyes, I can smell and touch and taste, but visuals for me grew out of not wanting to play on stage. I’ve always played from the back of the room, or onstage huddled over equipment with visuals going, and things for the audience to do, like canvas on the floor and paint. So the focus was not on ‘oh look, there are people on stage’, but ‘we’re in an environment with things to do and some sound as well.’”

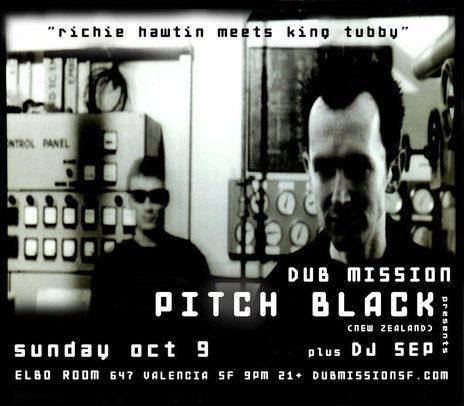

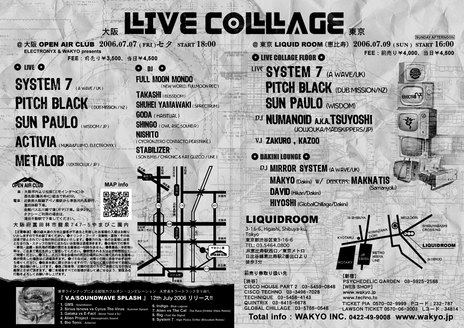

Through the first decade of the new century, Pitch Black continued to build its audience, especially in international territories, releasing several of its albums in America and Europe to support successful tours there.

Inevitably, however, Hodgson’s job running massive video installations for major sports events robs him of Pitch Black time, and it’s yet to be seen whether his recent move to London – a long way from Free’s Karekare base – will keep the duo ‘futureproofed’. He assured AudioCulture, however, that Pitch Black “still see ourselves as existing. While we are currently separate it’s not through a break-up, just a pause. It’ll be our 20 year anniversary in 2016, so we are planning something.”

And good to their word, Pitch Black released a new album Filtered Senses in September 2016 (followed a second album consisting of remixes of that record, called Invisible Circuits, in 2017), and played live dates in 2017 and 2018 both in New Zealand and Europe.